Suggested New Design Framework for CMAM Programming

By Peter Hailey and Daniel Tewoldeberha

Peter Hailey was a Regional Nutrition Specialist in the UNICEF East and Southern Africa Regional Office and is now Senior Nutrition Manager in the UNICEF Somalia Country Office.

Daniel Tewoldeberha has been a Nutrition Specialist with UNICEF Ethiopia since June 2005. Previously he worked with World Vision as a Health and HIV officer supporting health, nutrition and HIV projects in southern Ethiopia and with Save the Children US in both centre and community based programmes for managing acute malnutrition.

The authors would like to acknowledge the numerous people and their ideas, experiences and opinions shared with us over the years that have contributed to this paper. The authors would also like to acknowledge Orla O'Neill, Dr Mesfin Teklu, Amal Bennaim, David Doledec, Nicky Dent and Sylvie Chamois and the others we have forgotten (with apologies) who have kindly commented on the draft of this paper.

The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this article are those of the author. They do not necessarily represent the views of UNICEF, its Executive Directors, or the countries that they represent and should not be attributed to them.

The last fifteen years have seen unprecedented progress in the field of management of severe acute malnutrition (MSAM). Advances made in the understanding of the pathophysiology of severe acute malnutrition (SAM), the development of appropriate feeding and treatment protocols and the wide scale use of home-based (out-patient) treatment strategies have all contributed to reducing case fatality and increasing coverage.1,2,3 These achievements in the MSAM have also opened up an opportunity to integrate services into routine health care delivery in many countries. An increasing number of public health facilities and outreach services are now managing cases of SAM with none or minimal external support. This has enabled the unprecedented scale up of MSAM. In some countries this means hundreds or thousands of health centres offering Community-based Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM) at national or significant sub-national scale.

There is a need for a fresh look at the opportunities, challenges and implications of CMAM programming as it is now in many countries. This paper examines the suitability of the conventional assumptions regarding CMAM planning and implementation, in particular in areas of chronically vulnerable livelihoods and suggests a new approach to design for CMAM programmes.The MSAM has been traditionally seen as an emergency intervention with external inputs almost exclusively provided by donors, United Nations (UN) agencies and international non-governmental organisations (INGOs). This has resulted in the waxing and waning of external support based on the reported or perceived level of nutrition emergency, despite the constant presence of severely malnourished children throughout the year and over many years. This traditional model has not been adapted to the new reality of large scale, community based, continuous and Government led programmes. The conventional view is that programmes open based on emergency nutrition prevalence thresholds and close as the situation improves, often only to reopen in the next hunger season. This view is now changing with increasing commitment from decision makers and increased ownership and leadership by Ministries of Health (MOH) towards continued support to CMAM at scale.

The discussion below will lead the reader through the logic used to propose a more up to date framework for MSAM. The ideas are particularly appropriate in situations where nutrition related 'emergencies' are regularly declared and where, in reality, populations live in a chronic state of nutrition emergency. The prevalence of SAM (<-3 WHZ scores) is taken as reference point in two of the models, with a prevalence of 3% SAM suggested as a threshold for defining an emergency ('response trigger'). This is done to facilitate visualisation while recognising that the threshold for SAM may differ from country to country.

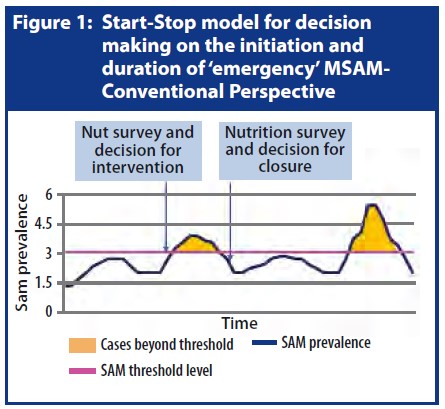

A conventional conceptual model to initiate emergency response to severe acute malnutrition: the Start-Stop Model

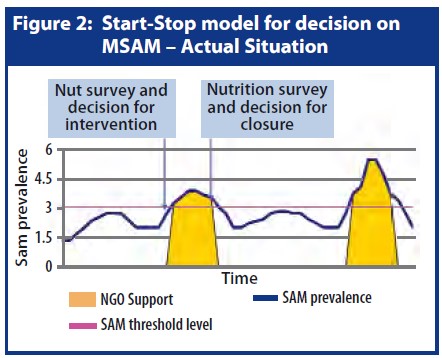

Agencies are able to win the attention of decision makers by providing information /evidence that the situation has exceeded the emergency threshold or will soon do so because of a number of aggravating factors (see Figure 1). This rightly implies that there is a risk of excess mortality associated with higher SAM rates beyond the 'emergency' threshold that requires immediate action. When budgeting for an intervention, implementing partners target all severely malnourished children in the affected area (Figure 2). Targeting only the excess cases above the threshold would be unethical and impossible.

Note: Usually thresholds of prevalence of Global Acute Malnutrition (GAM) are used as the principal indicator for emergency action. The ratio of SAM to GAM is extremely variable but often a decision to declare a nutrition emergency and to start channelling resources to CMAM is based on the GAM prevalence rather than that of SAM.

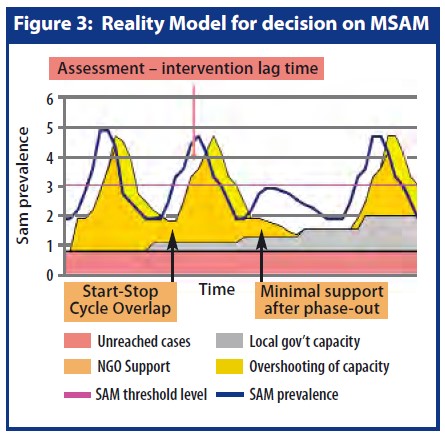

How the start-stop model is being adapted in the field: The Reality Model

Assessment-intervention lag time: The lag time between nutrition survey findings and management of malnourished children on the ground is mainly due to the time it takes to agree on declaring an emergency and then to mobilise resources. In this initial period whilst partners receive funding and mobilise staff, supplies and other needed resources, increased numbers of severely malnourished children remain in a critical situation and part of the crisis period has already passed.In the process of implementing the conventional model, the reality of operating in difficult circumstances forces changes, resulting in contradictions and distortions between what is said and what is done. Some of the events involved and are described here:

Stop Signal Lag Time: As with the start signal above, once a survey or assessment has shown the SAM or GAM rates have moved below emergency thresholds or the assessment indicates improvements it takes some time for an organisation to stop their input of resources or to hand over.

Start-Stop Cycle Overlap: Some agencies work using the start-stop model and stop quickly. Others stay longer and try to make the best use of remaining resources to continue support after the end of the nutrition emergency, until the programme is closed or a new emergency is declared.

Thus whilst both donors and implementing partners attempt to synchronise funding and interventions with the rise and fall of acute malnutrition rates, it is inevitable that there is a lag time between the signal for starting or stopping and actual starting or stopping of interventions. This situation becomes particularly accentuated in areas of chronic nutrition emergency where Start -Stop cycles regularly overlap with one another. The model in Figure 3 attempts to show this reality.

Thus whilst both donors and implementing partners attempt to synchronise funding and interventions with the rise and fall of acute malnutrition rates, it is inevitable that there is a lag time between the signal for starting or stopping and actual starting or stopping of interventions. This situation becomes particularly accentuated in areas of chronic nutrition emergency where Start -Stop cycles regularly overlap with one another. The model in Figure 3 attempts to show this reality.

Thresholds and government capacity analysis

The use of fixed prevalence thresholds was developed and has become entrenched as part of the Start-Stop model. The present approach to using thresholds also needs to change to reflect the reality and the changed implementation model. Momentum to change the conventional approach to using thresholds is also building because of the reported lack of evidence for the thresholds used at present4. Yet thresholds are required to make decisions.

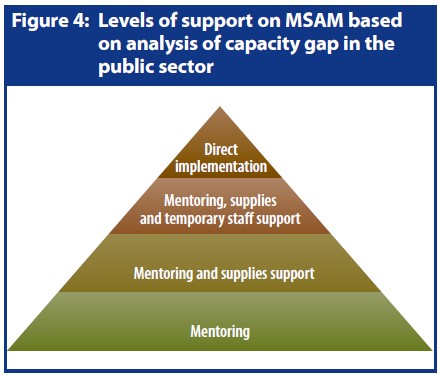

A threshold serves two purposes; the first to demonstrate that the situation has passed a critical point and secondly, to allow decisions to be made on what actions should be taken. In the case of SAM, the types of action taken should depend on the number of children estimated to be acutely malnourished and the capacity of the health system to cope with these children. Therefore, we suggest that an analysis of the capacity of the existing health system to cope with the estimated caseload is used as the principal basis for the decision on the level and type of external support that is required. This will have the advantage of adding incentive to interventions to address capacity of the health system as well as saving lives.

To date, there has been little analysis of how capacity-based response triggers could be used to define required external support packages that can build on the existing MOH structure and services, and reinforce the long term development aims of the country. A simple example of a system involving four thresholds and four corresponding degrees of resource inputs is shown in Figure 4. The resource inputs suggested in the pyramid move from simple support through increasing levels of support and substitution of Government services until an almost complete substitution of Government capacity - the 'therapeutic feeding in a tent' phase.

A combination of estimation of prevalence and analysis of Government capacity would be required to define each threshold coupled with an agreement on what type and level of support would be required at each level.

Using a prevalence based threshold without consideration of existing capacity also means that the programme design is often heavier than it needs to be. Implementing agencies tend to design and receive funding for CMAM programmes that assume because it is an emergency, a one size fits all approach requires additional resources that are further up the capacity pyramid e.g. resource substitution and agency led. These types of intervention are more intensive, restricting partners to supporting smaller numbers of centres and smaller geographic areas. This is a cost inefficient approach and limits the full potential of CMAM to increase coverage dramatically.

Thus the use of the conventional Start-Stop model and fixed prevalence thresholds is purely theoretical, outdated and does not fit the reality on the ground. The continued use of such a model is resulting in distortions in the design and implementation of the intervention that are damaging its efficiency, efficacy and sustainability and wasting resources.

Bridging Emergency and Development: Disaster Risk Reduction

The intermittent nature of support for the MSAM is in part due to the separation of emergency and development activities in different departments and funding arrangements in bilateral and multilateral agencies. This separate conceptualisation and implementation of emergency and development approaches, and the view that an emergency and associated funding is short term, means that the opportunity to use the emergency intervention and resources to build risk reduction approaches and address longer term aims is not capitalised upon. Ideally such opportunities would also be incorporated into existing or new development programmes so that both approaches are getting more value for money. However this assumes a degree of flexibility and responsiveness that is not normally found in development planning and budgeting.5

The gaps arising from the intermittent nature of emergency support are not limited to the MSAM. Recognised for some time, this has led to the concept of disaster risk reduction (DRR). DRR is a broad framework designed to avoid (prevent) or limit (mitigation and preparedness) the adverse effects of hazards like droughts, earthquakes or floods.6 The UN International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UN/ISDR) defines DRR as: "The concept and practice of reducing disaster risks through systematic efforts to analyze and manage the causal factors of disasters, including through reduced exposure to hazards, lessened vulnerability of people and property, wise management of land and the environment and improved preparedness for adverse events." Four relevant actions for the MSAM can be found in the definition of DRR: analysis, decreasing vulnerability, decreasing exposure to hazards and improved preparedness for adverse events. Analysis involves the use of early warning surveillance systems. An example of decreasing vulnerability could be better caring practices including breastfeeding, and improvement in public health environment, such as access to safe water and adequate sanitation for women and children, to improve baseline health and nutritional status. Food insecurity and disease could be regarded as hazards to be minimised.

The fourth point that is directly related to MSAM is improved preparedness for adverse events. The capacity of a health system to cope with increased needs for curative care for any disease or condition is a key part of preparedness and disaster risk reduction, especially in an area where nutrition emergencies are regular.

The need for a design framework and alternative thresholds for action: the New Framework for CMAM Design

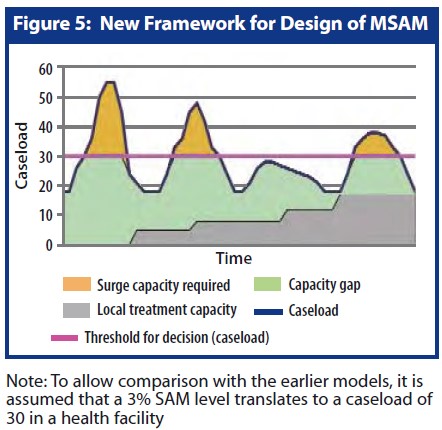

The new framework outlined in Figure 5 proposes a different way of looking at the MSAM so that there is better readiness and timely response in times of disaster, and continued capacity building/strengthening and integrated service delivery thereafter. It is an attempt to conceptualise what is already evolving in the field of MSAM and to reach a common understanding so that donors, UN agencies, NGOs and government can use an intervention model that is more appropriate to the new realities of CMAM programming.

The new framework focuses on the estimated caseload and capacity of the public sector instead of using emergency thresholds based on SAM or GAM prevalence to advocate for an outdated conventional response. The topmost golden part of the new conceptual model indicates the case load when the nutrition situation goes beyond one of the capacity based emergency thresholds. The lowest grey part shows the progressively increasing capacity within the public sector to manage severely malnourished children. In most countries, this increasing national capacity has been and still is being built using emergency funds and interventions. The middle green part represents the gap between the existing local capacity and the actual caseload below the threshold. Note that the threshold for level of resource input decision reflects a hypothetical caseload paralleling the emergency SAM or GAM threshold level.

As argued above, it is easier to mobilise and utilise resources for the topmost part as an 'emergency intervention'. However, during the declared emergency phase, the interventions are already addressing the (green) national capacity gap, largely by substituting resources but increasingly by building and strengthening capacity even during the emergency. Yet because of the use of outdated conceptual models and the divide between emergency and development, the de facto funding of the green area is not reaching its potential in simultaneously reducing mortality due to SAM and at the same time building/strengthening capacity of the health system. This double objective can be envisaged as a DRR approach to the MSAM, especially in areas of chronic nutrition emergencies.

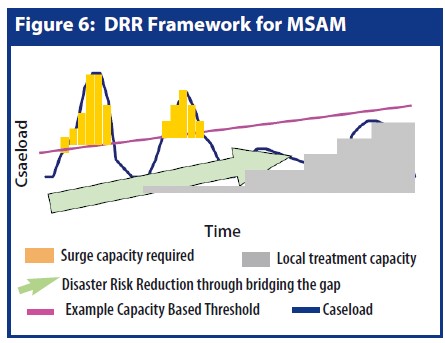

The model in Figure 6 is based on the Figure 5 framework and attempts to describe the contribution of the new conceptual model and use of alternative thresholds to DRR. The pink line represents one of the suggested capacity based thresholds, above which an external input of resources is required e.g. increased temporary staff represented by the golden vertical bars. The horizontal grey bars reflect the local capacity that is progressively growing over time. The diagonal green arrow represents the use of resources to build/strengthen local capacity. This continuous and adapted engagement is anticipated progressively to increase national capacity to handle the caseload, shifting all the proposed capacity thresholds upwards. The 'capacity based threshold' in this simple example steadily increases as Government capacity increases. Thus a response to increased prevalence of SAM due to a disaster and adapted to existing capacity can save lives and strengthen capacity during and after the disaster, thereby reducing risk, increasing preparedness and developing the health system.

As with any Health System strengthening approach, strengthening CMAM requires an increased attention to using data and systems for oversight, monitoring and audit. It is not just about developing guidelines, training, and when deemed necessary, increased external resources and substitution of government capacity. As scale is achieved and integration into health systems becomes more complete, an emphasis on service quality becomes the priority.

Therefore, agencies involved in CMAM need to re-examine their design frameworks and methods of implementation to bring together the concepts of DRR, capacity building/ strengthening, service quality, Government lead, and scale. Gone are the days of supporting a few centres in one or two districts designated to that NGO in the 3Ws (Who, What, Where) framework of the nutrition cluster or sector.

The new conceptual model has a number of advantages:

- In many countries, SAM is a daily challenge to the population. With updated design frameworks, SAM programming and specialist agencies, including donors, can better address this reality.

- Many of the areas that face repeated nutrition emergencies are known for chronic livelihood vulnerability and regular emergencies. A longer term view of support for the intervention, even during the emergency, would result in a more appropriate and cost efficient approach to addressing chronic nutrition emergencies.

- With a more nuanced approach to types of external support required, coupled with longer term objectives, the roles of CMAM partners can be redefined. Partners could broaden the geographical coverage of support interventions, play less of a 'hands on' role and focus on support/facilitation for MOH to manage services for high coverage and quality with emphasis on strengthening capacity for oversight, monitoring and audit.

Conclusions and Recommendations

For those of us involved in MSAM, the suggested new intervention framework stands in stark contrast to the old framework of intensive, externally resourced, tightly targeted and low coverage interventions. Despite the changes in MSAM over the last 15 years, the conceptual model used by donors and agencies specialised in CMAM has not really changed.

An unrealistic current model

According to the classic conceptual model (Start- Stop Model), MSAM is treated as a temporary phenomenon that starts and stops, in a similar fashion to polio, cholera or measles outbreak response and/or as if the 'non-emergency' SAM caseload during and after the emergency was being covered by regular development programmes (despite the fact that there was often no local capacity to hand over to). Indeed even the classic conceptual model is not the same as the actual implementation model when many non 'excess' cases of SAM are being treated during and between the emergency periods.

A new framework and alternative thresholds for actionThe unrealistic conceptual model coupled with the use of prevalence thresholds for action with a tendency to 'one size fits all' interventions has resulted in contradictions and distortions between what is said and what is done. Agencies have failed to take into account that while their own intervention might have a stop date, the need for CMAM is continuous. In fact in many cases despite the short term nature of individual donations, agencies have been implementing the same programme with short term goals almost continuously for many years, in the name of an emergency response.

The new conceptual model suggests that emergency resources for MSAM can have two objectives. The first objective is to reduce excess mortality due to raised levels of SAM and the second objective (also a DRR objective) is to strengthen and build capacity.

Instead of using a single prevalence-based threshold to decide on when to start and stop an intervention, a series of existing capacity based thresholds should be used (combined with prevalence estimates or not). This series of thresholds would be area specific and would be set according to the area health systems capacity to cope with increasing caseloads of SAM. The series of thresholds would then be used to decide on what type and intensity of external resource would be required as each level is passed. In addition to being a more realistic and practical use of thresholds, this would put the focus of interventions firmly on capacity building/ strengthening.

A controversial approach?

It is understood that we are working in a time when the emergency and development departments of almost all partners find it hard to define common ground and linkages. This common ground is defined by, as yet, fuzzy concepts such as Early Recovery or DRR and there is limited ownership of these concepts in either department. Furthermore, the often linear conceptualisation of the emergency-todevelopment continuum, and the supposition that there is limited or no Government involvement in emergencies, is coupled with the assumption that capacity building/strengthening is not possible during emergencies. However this ignores the reality on the ground. In almost all cases, emergency and development interventions are implemented in parallel in the same areas and through the same local government staff and communities. This is particularly true in slow onset, chronic and complex emergencies. Governments at many levels - community, health centre, district and central - are almost always involved throughout the emergency response that is often ongoing for many years and sometimes for many decades. In fact the state has "the primary role in the initiation, organisation, coordination, and implementation of humanitarian (emergency) assistance within its territory"7. We suggest that it is possible and necessary to use emergency resources to address the objective of capacity building/strengthening and thus effectively to link emergency and development through DRR - a diagonal approach to programming in difficult circumstances.

In the coming years, the priority for CMAM programming evolution remains one of integration of the approach into Government Health Systems as part of the community based fight to reduce mortality, as well as achieving significant scale and attaining a reasonable quality of care through health system strengthening. The arrival of an 'emergency' intervention onto the development stage presents a challenging transition for all involved. Whilst the transition is happening, emergency resources from donors, UN and NGO's are being used inefficiently. It is suggested that the diagonal approach to managing this transition is a more efficient approach than that currently used in the field.

Watch this space...

A further paper in a future issue of field Exchange will share some practical approaches being used in the Horn of Africa to use capacity based thresholds to make decisions on resource requirements for CMAM and to ensure capacity building/strengthening is an equal objective to that of saving lives during an emergency.

For more information, contact Peter Hailey, email: phailey@unicef.org and Tewoldeberha Daniel, email: tewoldeb2002@yahoo.com

1Golden M. The Development of Concepts of Malnutrition. Journal of Nutrition. 2002 (Supplement) (http://jn.nutrition.org/cgi/reprint/132/7/2117S)

2Collins et al, Key Issues in the Success of Community Based Management of Severe Malnutrition, Food and Nutrition Bulletin, vol. 27, no. 3 (supplement) © 2006, The United Nations University

3Ashworth A., Chopra M., Sanders D et al. WHO guidelines for management of severe acute malnutrition in rural South African hospitals: Effect on case fatality and the influence of operational factors. Lancet 363. 1110-15. 2004

4H Young and S Jaspers, 2009. thresholds.

5DFID. Disaster Risk Reduction: a development concern; a scoping study on the links between disaster risk reduction, poverty and development. 2004

6UN/ISDR. Living With Risk: a global review of disaster reduction initiatives, 2004

7UN Resolution 46/182, 1991.

Imported from FEX website