Can Care Groups influence health seeking behaviours? Results of an impact evaluation in north-eastern Nigeria

By Dieynaba S N’Diaye, Erin Elizabeth Harned, Maya Israeloff-Smith, Stephanie Stern, Main M Chowdhury, Ngozi Odichinma Omenazu and Armelle Sacher

Dieynaba N’Diaye is a Research Advisor in the Expertise and Advocacy Department at Action Against Hunger (AAH) France. She holds a PhD in Epidemiology.

Erin E. Harned worked for AAH as Grant and Reporting manager in Nigeria and Jordan. She is now studying quantitative research techniques and strategies at Columbia University.

Maya Israeloff-Smith worked with AAH as Head of Nutrition and Health in Nigeria and later as an Emergency Nutrition Expert in South Sudan.

Stephanie Stern is a knowledge broker at AAH where she pilots the Knowledge LAB unit to reinforce AAH’s learning culture and pilot innovative ways to bridge the gap between research, knowledge and action.

Main M Chowdhury has worked in nutrition and health programmes with AAH for over seven years in South Asia, Middle East and Nigeria.

Ngozi Omenazu is a Nutrition Sector Manager for AAH working in Yobe State, North-Eastern Nigeria. She is a Biochemist with a Master’s degree in Human Nutrition.

Armelle Sacher works as Social Behavior Change and Gender Transformation Technical Advisor for AAH USA.

Action Against Hunger would like to thank the Yobe State Primary Health Care Management Board and the Yobe State Ministry of Health for facilitating access to the State health database. Without their support, this evaluation would not have been possible. The authors would also like to thank the Nigeria country team, in particular the project teams for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Operations (ECHO) and INP+ as well as the monitoring and evaluation and nutrition technical teams, for their contributions to this evaluation. This study was financed by AAH France in December 2018.

Context

Escalating violence between the Nigerian armed forces and armed opposition groups in Northeast Nigeria has caused mass displacement (peaking at 2.2. million individuals) and a protracted humanitarian crisis. According to the 2017 Humanitarian Response Plan, 8.5 million individuals were in need of humanitarian assistance, of which 6.9 million were in need of health care, 3.4 million in nutritional support, 2.3 million in emergency shelter and 3.6 million in water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH).

Action Against Hunger (AAH) has operated in Nigeria since 2010. AAH is a key partner in two multi-sectoral projects within conflict-affected areas of Northeast Nigeria (Jigawa, Yobe and Borno states) - the INP+1 and a project of the European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Operations (ECHO). The INP+ included community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM), micronutrient supplementation, infant and young child feeding (IYCF) counselling, social protection and social and behaviour change for nutrition and health outcomes. The ECHO project aimed to protect and promote nutrition security of vulnerable populations in northeast Nigeria through WASH and nutrition activities including CMAM, distribution of hygiene kits and promotion of health behaviour change. AAH delivered nutrition related activities in both programmes in collaboration with primary health care authorities at state, district and health facility levels. Embedded within these activities in Yobe and Borno states is the Care Groups approach, implemented between 2017 and 2019 to support nutrition and health behaviour change (Box 1). This article presents the results of a mid-term evaluation of the AAH Care Group programme in Northern Nigeria between December 2018 and January 2019, undertaken to understand the impact of this approach to inform future scale up.

Box 1: Care Group approach

The original Care Group Model involves the establishment of groups of 10-15 female volunteer community-based health educators, trained and supervised by field staff. Each volunteer is responsible for regularly meeting and visiting 10-15 of her neighbours, sharing what she has learned and facilitating behaviour change at household level. The purpose of this approach is to reach every beneficiary household with inter-personal behaviour change communication. Care Groups also provide a structure for community health information systems that report on new pregnancies, births and deaths that are detected during home visits. More information is available at https://caregroupinfo.org/

The Care Group approach in northeastern Nigeria

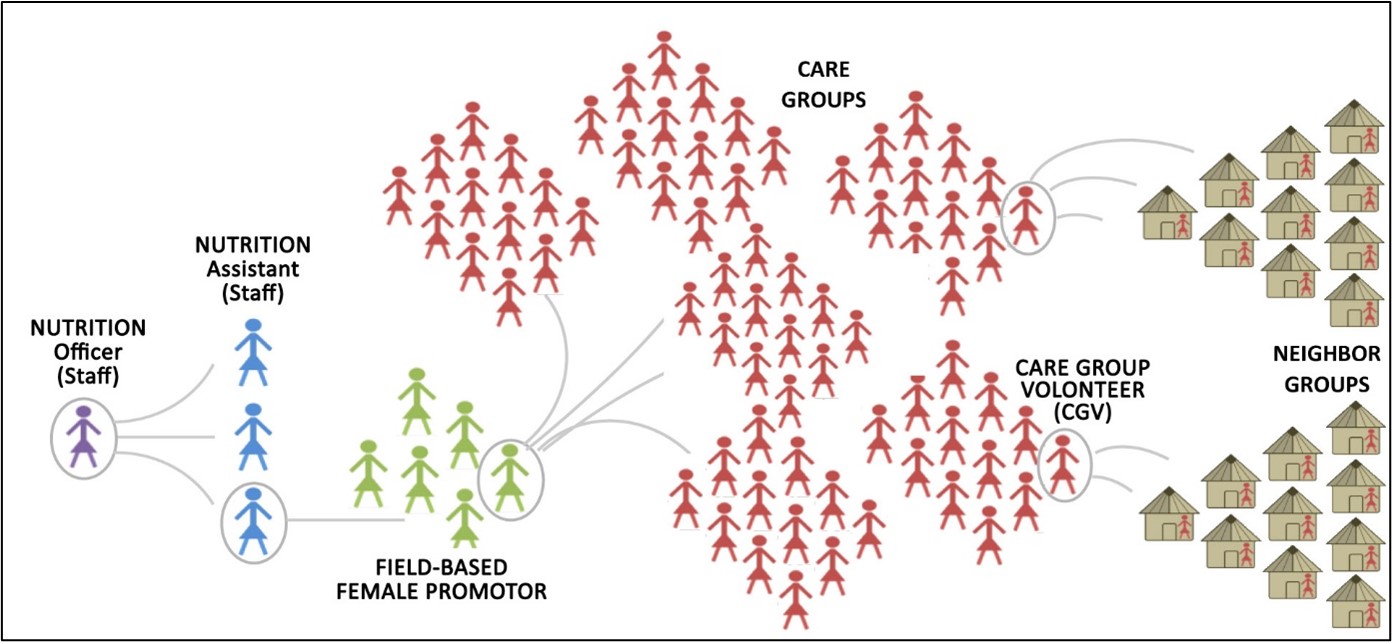

The Care Group approach was implemented using a cascade model, whereby AAH nutrition staff recruited and trained paid field-based health promoters in each geographic area (women from target communities with basic literacy skills). AAH staff met with each group of 10-15 promoters monthly from April 2017 to train them as trainers on one of 20 planned lessons (Box 2). Lessons are targeted to pregnant women and mothers or caregivers of children under two years of age and cover key maternal and child health topics. Following each lesson, health promoters trained groups of 10-15 volunteer community-based health educators, called lead mothers or care group volunteers, who each then shared the lesson with 10-15 neighbour households through monthly meetings and home visits (Figure 1). Through this approach, one AAH staff nutrition assistant was able to reach between 5,400 to 8,100 households each month.

By 2019, the Yobe State Care Group project was the largest Care Group activity implemented across the AAH network, with approximately 146,500 Care Group members directly reached each month through face-to-face activities. Although there was some turnover of volunteers seen in Borno State, as Yobe state was at the time a stable context with little population movement, volunteer turnover was low.

Figure 1: The Care group cascade used in Nigeria (illustration adapted from Care Groups: A Reference Guide for Practitioners 2016)

Box 2: Care group lessons

INTRODUCTORY MODULE (training of lead mother/promotor on facilitation skills)

Part 1: Adult Training Methodology

Lesson a: Communication and facilitation skills for health promoters

Lesson b: Communication and facilitation skills for lead mothers

Lesson c: Session methodology for health promoters

Lesson d: Session methodology for lead mothers (shortened method)Part 2: Care Group Introduction

Lesson a: Introduction to the activity, ground rules and topics.MATERNAL NUTRITION AND HEALTH

Lesson 1: Nutrition for pregnant and breastfeeding women – frequency of meals and snacks

Lesson 2: Dietary diversity for women during and after pregnancy

Lesson 3: Ante-natal care (ANC) and danger signs in pregnancy

Lesson 4: Post-natal care (PNC)INFANT AND YOUNG CHILD FEEDING PRACTICES

Lesson 5: Importance of early initiation of breastfeeding

Lesson 6: Positioning and attachment

Lesson 7: Exclusive breastfeeding for first six months

Lesson 8. Breastfeeding on demand

Lesson 9: Overcoming common breastfeeding difficulties (part one)

Lesson 10: Overcoming common breastfeeding difficulties (part two)

Lesson 11: Complementary feeding for children aged 6 - 8 months

Lesson 12: Complementary feeding for children aged 9 – 11 and 12-24 monthsESSENTIAL HYGIENE PRACTICES

Lesson 13: Diarrhoea transmission, prevention and treatment

Lesson 14: Hand washing and tippy taps

Lesson 15: Faeces disposal, improved latrines

Lesson 16: Improved water sources and safe water for drinkingCHILD HEALTH

Lesson 17: Health services in our community including immunisation, vitamin A, deworming, oral rehydration solution and zinc

Lesson 18: Malnutrition: mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) screening and availability of community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) programming

Lesson 19: Feeding a sick child

Lesson 20: Danger signs: when to take your child to the health facility

Methodology

AAH carried out an evaluation of both the INP+ and ECHO Care Group programmes in northeastern Nigeria between December 2018 and January 2019. By the beginning of the evaluation the INP+ and ECHO projects had completed 14 lessons, covering the modules related to maternal nutrition and health and infant and young child feeding.

Data from health management information system (DHIS) of the Nigerian Federal Ministry of Health covering the two project areas (Yobe and Borno States) were compared between January 2015 (baseline) and November 2018, following implementation of the lessons (care group lessons were launched in April 2017 for INP+ and July 2017 for ECHO, respectively month #28 and #32 of observation). Indicators described in Box 3 were reviewed for evidence of outcome-level improvements in health seeking behaviours. It was not possible to include breastfeeding indicators as these were not available within the DHIS. Coverage of services was calculated as total population divided by total health facility attendance.

The difference-in-differences model was used to compare the median for each indicator to account for outliers. Differences were compared between local government authorities (LGAs) that had the intervention and those that did not in order to demonstrate how much any change in intervention areas could be attributed to the AAH programme. Comparison non-intervention LGAs were selected based on descriptive data on population and access to facilities.

Box 3: Indicator descriptions

- Antenatal care visits (ANC): number of women receiving antenatal care divided by the total number of expected pregnancies estimated by the health system based on national statistics. This indicator documents women’s access to and use of health care while pregnant and is recorded as a percentage.

- Postnatal care visits: number of newborns receiving a postnatal check divided by number of live births. This indicator documents percent of first postnatal visits held within three days of delivery, which captures the coverage of early postnatal care and reflects both the accessibility of and how accepted postnatal care is in LGAs across Yobe state.

- Healthy facility utilization rates: frequency of health facility use. It is calculated as number of days multiplied by number of beds/ number of beds occupied on every day.

- Infant mortality rates: infant mortality rate (per 1,000) for children under 12 months of age

Low birth weight (LBW): number of births per 1,000 during which the child was under 2,500 grams

Results

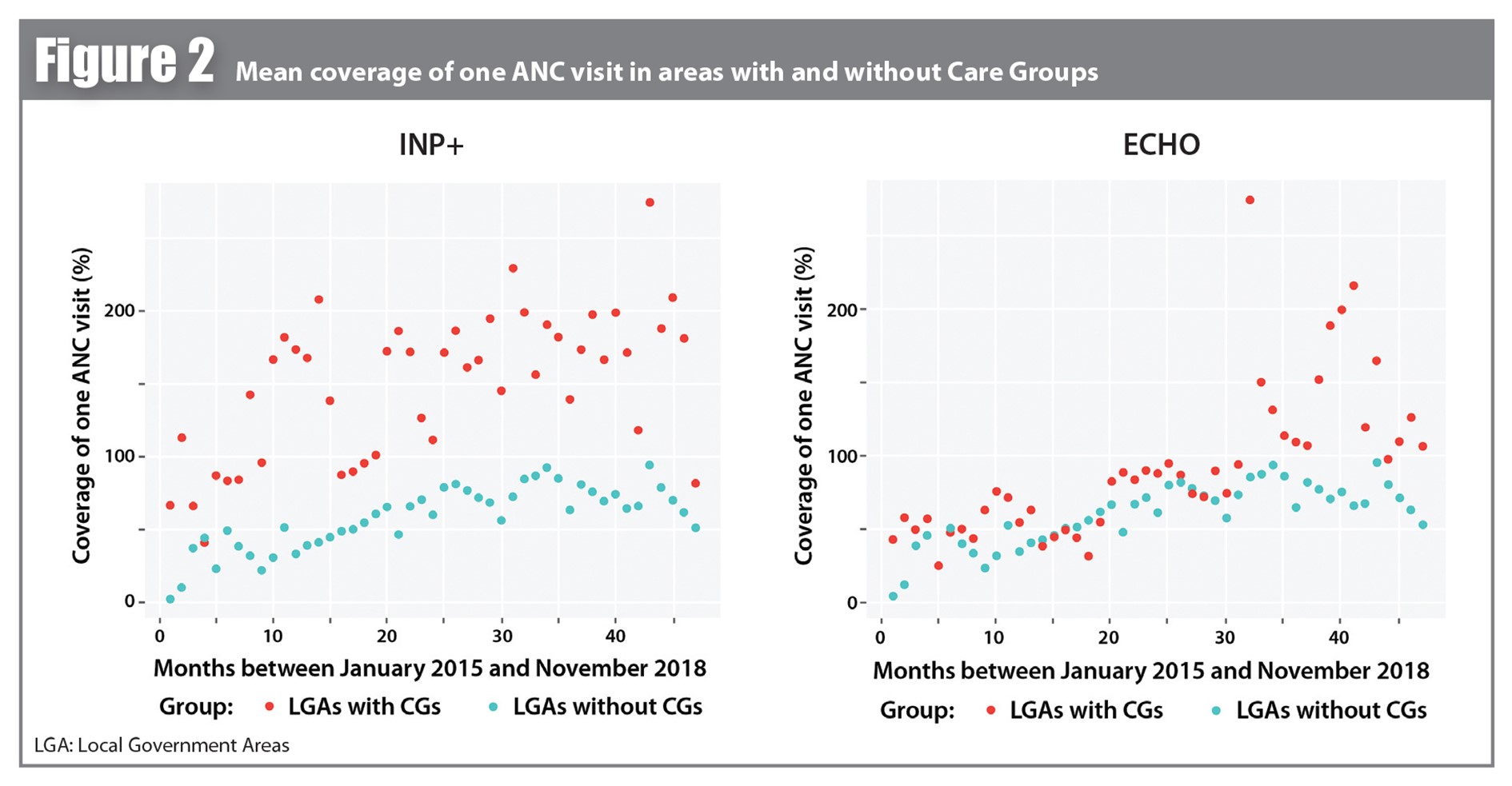

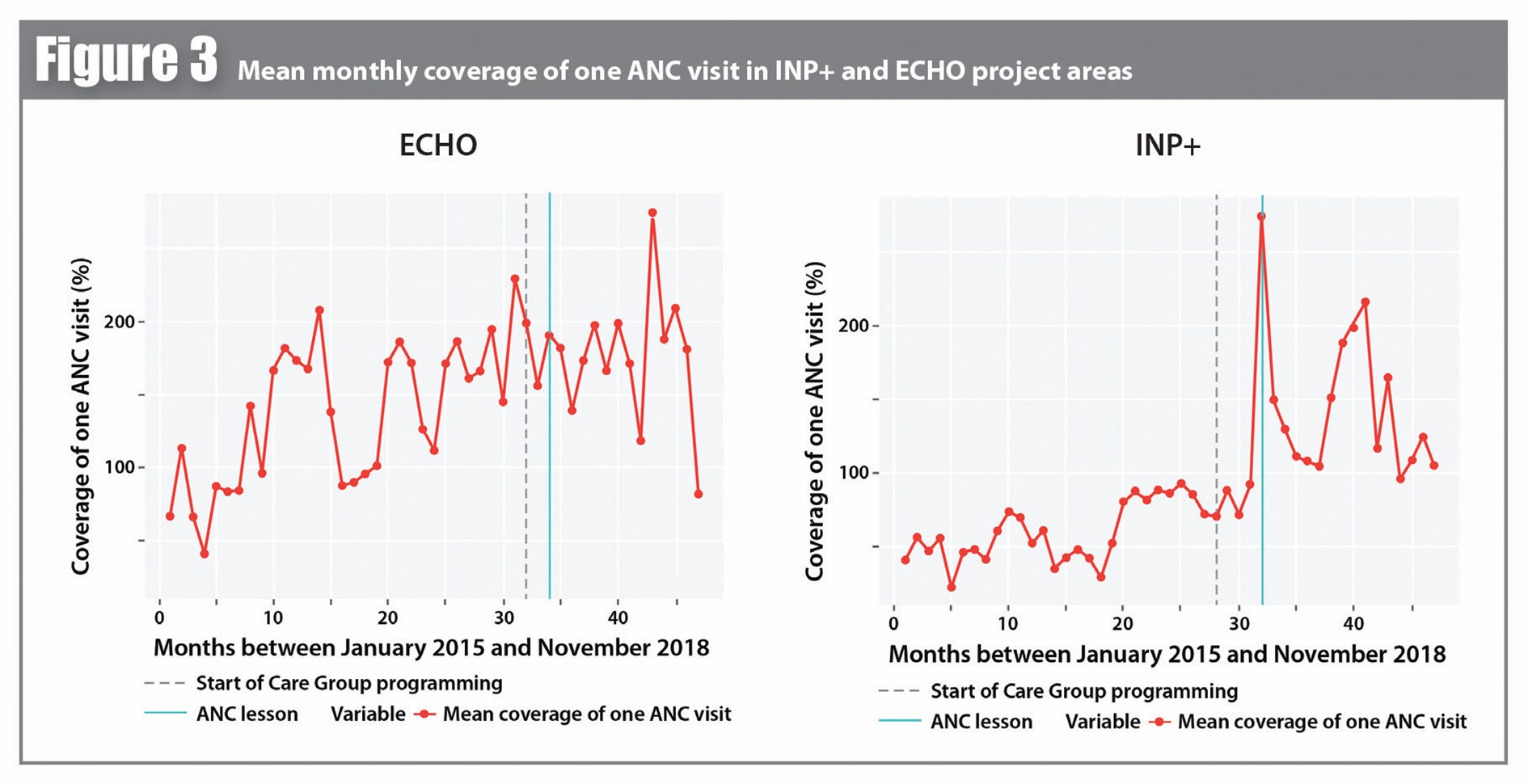

The strongest improvement in uptake of health services was seen in ECHO LGAs that received the Care Group intervention, particularly in ANC visits. In intervention LGAs, average coverage of attendance at one ANC visit (based on expected pregnancies) was 91% in INP+ areas and 149% in the ECHO areas compared to 58% in those without (Figure 2). In ECHO intervention LGAs, increases were observed within the month that the ANC lesson was carried out (Figure 3). This may signal a relatively quick, large effect on behaviour change, although this result could be affected by whether pregnant women were due an ANC visit in that month. The DHIS provides a global picture at LGA level and does not allow a link to be made between individual data related to individual pregnancy and visits.

In LGAs with Care Groups, the average coverage of attendance at all four ANC visits was 4.4% in the ECHO areas and 3.6% in the INP+ areas compared to 2.1% in those without. However, coverage rates did not trend consistently following the intervention and ANC attendance and facility utilisation rates declined again in late 2017 (month #36) as well as in early, mid- and late 2018 (month # 42 and 47).

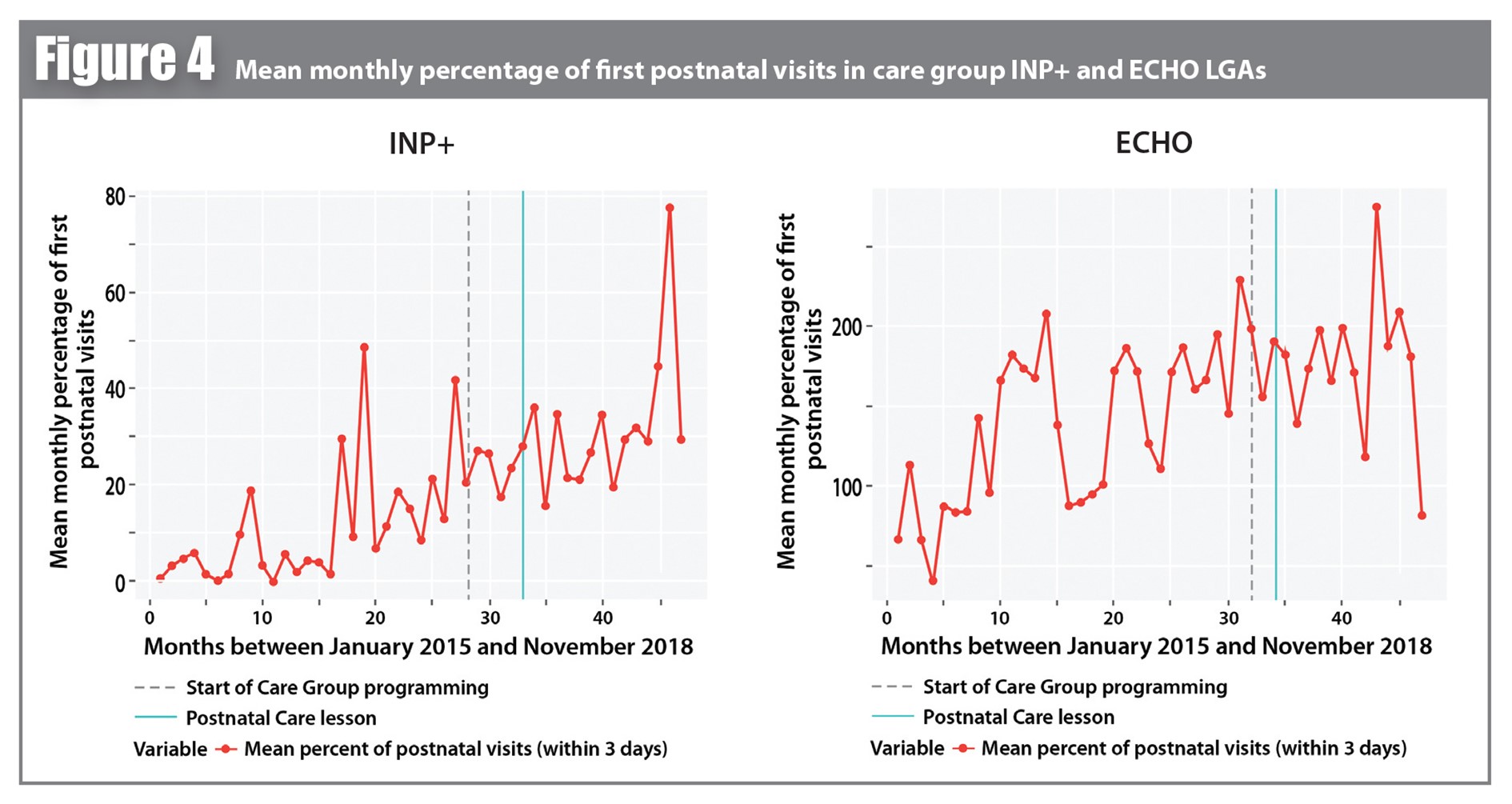

Mean percentage of postnatal visits (within three days of delivery) (Figure 4) varied following the start of Care Group activities. The median percentage of early postnatal visits was 15.5% in the ECHO area and 27% in the INP area, compared to 14% without. Increases in postnatal attendance in both INP+ and ECHO areas were often observed while ANC and facility use declined, particularly in June and December 2017 (months #31 and #36). These dates coincide with the end of harvests in northern Nigeria, but potential association between the two events requires confirmation, as holiday celebrations or insecurity could also account for the shifts. Overall, health facility utilisation increased during the period in both project areas.

Changes to mean infant mortality and LBW rates could not be captured by the difference-in-differences model, due to poor or absent trends in these data. Changes in LBW rates were noted in INP+ areas only where, between April 2017 and November 2018 (18 months of Care Group implementation) the average LBW was 11% in Care Group areas compared to 15.83% in areas without. However, improvements cannot necessarily be associated with the Care Group approach, as other components were implemented within the same multisectoral project over the same period of time, and LBW rates also declined in INP+ areas pre-implementation and in non-Care Group areas. Any change in these indicators as a result of the Care Group intervention will take time to be realised, and therefore may not be captured in this short window of time.

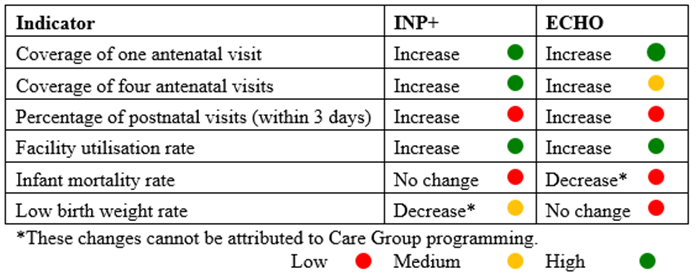

Table 1 summarises findings, noting the direction of each of the observed changes for each indicator per project. A ‘Result Reliability Index’ was calculated according to data quality and applicability of the difference-in-difference model. The relative strength of these results is color-coded as low, medium and high. Care Group programming was most strongly associated with a rapid improvement in health facility utilisation.

Table 1: Summary of Indicator Changes

Discussion

The results indicate that the Care Group approach was associated with some important positive effects on health seeking behaviors, in particular for the first ANC visit, and some marginal increases in PNC utilisation. When comparing the INP+ and ECHO areas, the magnitude of differences and period of time prior to the onset of observed changes were similar, indicating a positive effect of the Care Group approach under both projects. However, the relatively smaller short-term increase in coverage of the four recommended ANC visits suggests that the uptake of ANC services was not maintained over time.

Lessons learned about the evaluation process

The national data system in Nigeria was robust enough to ensure representation of the target population. However, data quality was compromised to some extent by coding errors, misrepresentation of data by facilities (under reporting of mortality rates), and in some cases by incomplete data owing to security issues. Furthermore, missing observations (2%) and outliers impacted reliability of the results. Ensuring best practice in data collection, monitoring and management would improve data reliability and therefore the quality of future evaluations. ANC coverage was calculated on the basis of expected pregnancies ((number of pregnant women receiving antenatal care/ total number of expected pregnancies)*100) rather than the number of actual pregnancies. This could potentially have skewed the results. Efforts should be made to build and closely monitor indicators related to actual health status to better assess the approach’s impact. Furthermore, there are considerable contextual factors, such as seasonality and insecurity, that could have impacted health centres attendance and health outcomes, which were not taken into account in the evaluation.

Indicators relating to breastfeeding and IYCF practices would add great value to such evaluations in future as these are key indicators of care practices. Qualitative surveys and key informant interviews would also reveal critical information around women’s workload, rest, level of stress, access to social support and birth spacing, which could all influence key health and nutrition outcomes. Analysis of dietary diversity would also be helpful to provide more insight into diets that influence health and nutrition outcomes.

Lessons learned on project implementation

Adjustments could be made to the Care Group approach to ensure and maintain positive behaviour change over time. The curriculum may need be implemented over a sufficiently long time period to enable the four ANC visits to occur, with the ANC lesson introduced at the beginning of the curriculum and repeated emphasis of the importance of this repeated throughout the course. In general, repeating lessons on key topics to remind attendees and capture newcomers could help to sustain behavior change. Volunteers could also be trained in methods to promote adherence such as the development of individual action plans for pregnant women; conducting of follow-up visits; and use of a recall system for visitations (setting phone reminders, ‘buddy’ system and visual aids could be explored).

Coaching volunteers on analyzing the neighbor group register data might be an effective way to target newly pregnant woman for home visits to encourage them to attend ANC, nutrition and pregnancy care. Consulting the register could also facilitate the identification of new mothers unlikely to attend group sessions who therefore need home visits to receive breastfeeding counselling and postnatal care sensitisation. Regular formative research is needed to understand barriers and enablers of behaviour adoption across each topic of the curriculum to constantly improve the approach.

Next steps

The INP+ project ran until June 2019 and the ECHO project until July 2019, and nutrition and Care Group’ activities were handed over to the State and LGAs health’s authorities in the context of the adoption of a government health extension worker system. Further investigation is needed to document how the Care Group approach has evolved since it has been absorbed by local authorities. This could help to inform guidance on the design of a hybrid Care Group model that could be easily integrated and managed in the context of health systems with limited resources.

Conclusion

The Care Approach implemented by AAH in northern Nigeria provides an example of widespread roll out of behaviour change communication embedded within a wider multi-sectoral programme. The mid-term evaluation demonstrated some positive impacts on health-seeking behaviours, although maintenance of behavior change remains a challenge and a longer period of observation would be needed to capture a potential effect on LBW. It also identified important challenges in the evaluation of the Care Group approach and the importance of considering the wider context, including barriers and enablers of behaviour change, as well as wider drivers of key health outcomes. The results also indicate that, while the Care Group approach provides a means of reaching a large number of people with health messaging to promote behaviour change, and therefore has enormous potential for impact, there is still much to learn about the implementation of this form of programming. The ongoing programme adopted by the Nigerian government will provide an important source of learning in the years ahead, which AAH hopes to support with continued evaluation and reflection.

For more information, please contact Dieynaba S N’Diaye at dndiaye@actioncontrelafaim.org1 INP+: Integrated basic nutrition response to the humanitarian crisis in Borno and Yobe State implemented by a consortium of AAH, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and World Food Programme (WFP) funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID).