Evidence Informed Decision-Making Process on Nutrition in Ethiopia

Tesfaye Hailu has an MSc in Human Nutrition. He has worked for the Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI)1 for the last eight years as a researcher. He is also a member of the Scientific and Ethical Review Committee of the EPHI.

Tesfaye Hailu has an MSc in Human Nutrition. He has worked for the Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI)1 for the last eight years as a researcher. He is also a member of the Scientific and Ethical Review Committee of the EPHI.

Knowledge gained through research can help to improve policies, programmes and practices within a nutrition service delivery system and can contribute towards significant improvements in the nutritional status and nutrition equity of a country and beyond.

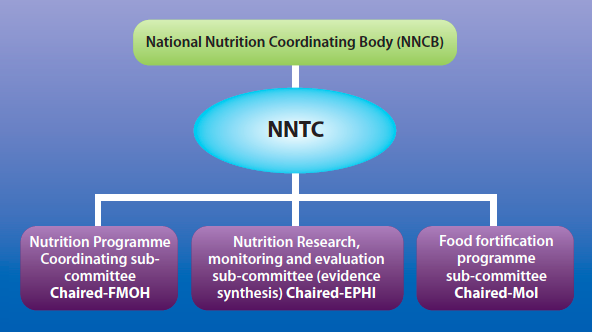

Coordinating mechanism

The government high level National Nutrition Coordination Body (NNCB) is the primary mechanism for leadership, policy decisions and the coordination of Ethiopia’s National Nutrition Programme (NNP). The implementation of this programme began in 2008, using a multi-sector and life-cycle approach. The NNP’s five-year plan was revised in line with the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) for the years 2013-2015. The MDGs were also used for the development of the country’s second five-year NNP (2016-2020).

The NNCB includes government sectors, partners, civilsociety organisations, academia and the private sector. Under this body is the National Nutrition Technical Committee (NNTC), comprised of senior nutrition experts from the same sectors. This committee is divided into three sub-committees:

- Nutrition Programme Coordination Sub-Committee chaired by the Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH);

- Nutrition Research, Monitoring and Evaluation Sub-Committee chaired by the EPHI; and

- Food Fortification Programme Sub-Committee chaired by the Federal Ministry of Industry.

While these committees function at a national level, there are other, similar, multi-sector nutrition coordination programme implementation arrangements in place at regional, district (woreda) and ward (kebele) levels, using the decentralised structure. The terms of reference, membership, frequency of meetings and roles and responsibilities of sectors are detailed to ensure transparency in conduct.

Generating appropriate evidence to inform national policies and programmes

The Nutrition Research, Monitoring and Evaluation Sub-Committee is led and coordinated by EPHI. Members of the Sub-Committee access the research agenda of EPHI and generate, translate and deliver evidence to decision-makers to answer their policy and programme questions. For example, Ethiopia is currently planning a national food fortification programme; in order to ensure appropriate fortification, decision-makers assessed the existing evidence summarized by EPHI and invested in novel, context-specific research. The latter entailed a National Food Consumption Survey and a National Micronutrient Survey which collected data on Ethiopian food intake and micronutrient status, respectively. EPHI is also reviewing existing data, including recently published systematic reviews, to produce policy briefs on the relevance of zinc fortification to Ethiopia. Furthermore, EPHI conducted the National Nutrition Survey in 2015. The results of this survey were reported to the FMOH to help set targets for the NNP of 2016-2020.

Information dissemination

While nutrition academics from EPHI are mandated to inform nutrition actions, various other academic institutions have also linked with the EPHI’s Department of Food Science and the Nutrition Research Directorate specifically to provide evidence-based answers to questions on nutrition programmes from decision-makers. Evidence produced by these institutions is shared across academia through annual conferences and is subsequently compiled and presented to appropriate government ministers to aid programme reform. A website is also used to disseminate research outputs.

Main barriers identified so far and suggested ways forward

Despite the ongoing efforts to use evidence in making decisions about nutrition programmes, there are still a number of gaps and barriers to the process of decision-making in Ethiopia. These currently include:

- Poor use and integration of research outputs in programme and policy changes;

- Insufficient personnel trained to work on producing systematic reviews to inform policy;

- Poor use of health economics evaluation papers;

- High attrition rates of trained nutritionists in government sectors;

- Difficulties in finding synergies between the agendas of different development partners; and

- Poor linkages with the sub-national (regional) level Some of these barriers can be addressed through the following:

- Short and long-term training of personnel in performing systematic reviews and full health technology assessments;

- Developing methodological tools and processes for identifying and setting priorities in nutrition with decision-makers;

- Establishing a national nutrition database of previous and ongoing research and programmes performed within Ethiopia by the different entities (NGOs, donors, universities, EPHI, etc.); and

- Evaluating the systematic process of decision-making, from priority-setting to the implementation of evidence-informed policy briefs.

Thus far, Ethiopia has mapped the stakeholders involved in evidence-informed decision-making in nutrition, identified priority research topics by talking to these decision-makers and various other key stakeholders, and built the capacity of some researchers in nutrition academia on evidence synthesis. The government has also recognised the importance of evidence in policy-making. Many of these actions have taken place due to Ethiopia joining the EVIDENT Network (Evidence-informed Decision-making in Health and Nutrition; see www.evident-network.org), The network is facilitating Ethiopia in bridging the gap between science and policy and has therefore become an integral part of EPHI’s nutrition research agenda and the next five-year NNP.

In addition, Ethiopia’s experiences with the SURE collaboration (Supporting the Use of Research Evidence; see www.who.int/evidence/sure/guides/en) and its readiness to accept evidence for better implementation of programmes to improve the nutrition outcomes of the country will be pursued to help overcome some of the barriers to evidence-based policy and decision-making.

Finally, a key lesson learnt so far is that it is essential to have a good governance structure in a country in order to facilitate the acceptance of evidence-based policies and the concept of evidence-informed decision-making and what it entails.

Masresha Tessema and Yibeltal Assefa and Dr Ferew Lema at the Federal Ministry of Health, Ethiopia have contributed to this article.