Debunking urban myths: access & coverage of SAM-treatment programmes in urban contexts

By Saul Guerrero, Koki Kyalo, Yacob Yishak, Samuel Kirichu, Uwimana Sebinwa and Allie Norris

Saul Guerrero is Head of Technical Development at ACF-UK and a founder of the Coverage Monitoring Network. Prior to joining ACF, he worked for Valid International in the research & development of the Community Therapeutic Care (CTC) model. He has supported SAM-treatment programmes in over 20 countries.

Koki Kyalo is the Programme Manager for the Urban Nutrition Programme in Concern Kenya. She has over 4 years of experience in integrated management of acute malnutrition (IMAM) programming. She also played a critical role in the roll out and expansion of IMAM services in the urban slum settings of Nairobi and Kisumu.

Yacob Yishak is the Health and Nutrition Programme Director of Concern Worldwide Kenya. He is responsible for the overall coordination of technical and managerial functions of the programme. He has worked with Concern for the last five years in nutrition programing, assessment, research and conducted a number of national and regional training in nutrition and mortality assessment. He is a Master trainer in SMART methodology.

Samuel Kirichu is an Assistant Project Manager – Survey and Surveillance at Concern Worldwide (Kenya). Samuel has over two years’ experience in conducting SQUEAC assessments both in the urban and arid and semi-arid land (ASAL) areas. He holds a Master of Science (Statistics) and a Bachelor of Science degree (Applied Statistics).

Uwimana Sebinwa is Regional Coverage Advisor for the Coverage Monitoring Network. She has been implementing nutrition programmes with ACF in different emergency and development contexts. She now supports organisations in carrying out coverage assessments.

Allie Norris is a Social Development Advisor and Coverage Surveyor for Valid International. She has conducted 13 coverage assessments using the SQUEAC, SLEAC and S3M methodologies in seven different countries over the last 4 years.

The authors would like to thank the Coverage Monitoring Network (CMN) team, including Jose Luis Alvarez and Ines Zuza, and Concern Worldwide in Kenya for their valuable contributions. Thanks also to NGOs, Ministry of Health and UNICEF staff in Kenya, Liberia, Haiti, DRC, Djibouti and Afghanistan for their support during the implementation of coverage assessments. Finally, thanks to Mark Myatt for his support with data analysis and visualisation.

Introduction

Over the last decade, the treatment of SAM has been mainstreamed and rolled out around the world. Today, there are more SAM treatment services than ever before, covering a wider range of contexts. As part of that transition, SAM treatment has transcended from solely focusing on isolated, rural areas (often during/following a period of food insecurity and conflict), to urban areas in more stable, developmental contexts. This transition has exposed SAM treatment programmes to a number of variations in the causes (actual and perceived) of SAM and the way in which people respond to it, as well as variations in the way in which SAM treatment is delivered. With the introduction of easy-to-use coverage assessment methodologies, and their application in a variety of urban contexts including Kenya, Liberia, Haiti, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Afghanistan, Cameroon and Zambia, a growing body of evidence about SAM treatment in urban settings is emerging. What this evidence provides is a series of lessons about the challenges and opportunities presented by urban environments, and how, in reality, barriers and boosters to access are often dramatically different to how they were once perceived. As our understanding of urban programming grows, many of the underlying urban myths that have shaped SAM treatment programming have been exposed. This article draws from a range of experiences in different urban contexts to shed light on four of the most common myths influencing SAM programming.

Expectations & performance

There is a widespread consensus that urban contexts are unique, with specific sets of challenges and opportunities that affect access to primary health care programmes. In the case of SAM treatment, there are no universally agreed standards to evaluate how accessible SAM treatment programmes should be in urban environments. The only such available reference is the SPHERE Standards, which stipulate coverage rates of >50% for rural programmes, >70% for urban programmes and >90% for camp settings. These standards are clearly designed for humanitarian, emergency programmes and are therefore not always applicable to the developmental, urban environments in which SAM treatment is currently delivered. But there is a profound assumption underpinning SPHERE standards that has come to shape expectations of coverage in urban programmes; that SAM-treatment programmes in urban programmes should reach a higher proportion of the affected population than its rural counterparts.

This in turn implies that access is easier in urban environments, that barriers are somehow more easily surmountable. Part of this belief stems from the fact that access is (wrongly) equated with distance, something which is indeed significantly different compared to rural environments. But physical access is only a part of it; coverage is ultimately defined by the capacity of a programme to enrol a high proportion of the affected population (uptake) and the capacity to retain these cases until they are successfully cured (compliance). Coverage and defaulting data therefore provide the necessary evidence to determine whether these assumptions about easier access in urban environments are justified.

Defaulting rates in urban contexts

Evaluating the comparative performance of urban programmes requires a baseline, a sense of what the average or expected defaulting rate is in a ‘normal’ SAM treatment programme. SPHERE stipulates that the default rate of a SAM treatment programme should be <15%. This threshold is corroborated by a recent analysis carried out by Action Contre la Faim (ACF) with publically available data from (urban, rural and camp) SAM treatment programmes (n =85 programmes) covering the period 2007-2013, which found a median defaulting rate of 13%.

Using these two figures as a reference, we find that defaulting is higher in urban SAM treatment programmes than in any other setting. Coverage assessments carried out in Lusaka (Zambia) in 2008 found defaulting of up to 69% of total exits in some facilities. Similar assessments carried out by the French Red Cross in urban Maroua (Cameroon) in 2013 found defaulting rates of 28%. Data previously published in Field Exchange (Issue 43) has shown the challenges faced by Concern-supported SAM treatment services in Nairobi (Table 1). Together this body of data suggests that compliance is actually lower (defaulting is higher) in urban environments.

| Table 1: Data from Nairobi SAM-treatment programme | ||||

| Year | No. of Admissions | Cure Rate | Death rate | Default rate |

| 2008 | 1,607 | 48.4% | 2.4% | 47.0% |

| 2009 | 2,737 | 67.4% | 3.1% | 28.1% |

| 2010 | 4,669 | 76.0% | 2.0% | 21.0% |

| 2011 | 6,117 | 81.4% | 1.8% | 16.8% |

| 2012 |

6,859 |

85.2% | 1.0% | 10.8% |

Some of the most extensive and diverse information on defaulting in urban contexts has come from SAM treatment programmes in Port-au-Prince (Haiti). Inter-agency coverage assessments carried out in 2012 found a range of defaulting rates across different agencies (from 4% to 39%). What these assessments also found was that defaulting was more pronounced in programmes operating in urban slums. And this raises an important point: urban areas are not homogenous but are a patchwork of different socio-economic groups facing different barriers to access. Designing and developing SAM treatment programmes for an ‘average’ urban population risks the marginalisation of some of these populations.

Coverage rates in urban contexts

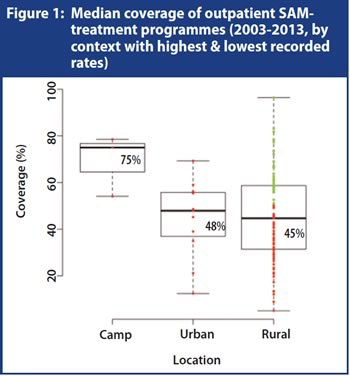

There is additional evidence available to suggest that urban SAM treatment services are not more accessible than rural programmes. A sample of over 100 coverage assessments (including rural, urban and camp programmes) carried out between 2003 and 2013 shows that on average, urban programmes perform only marginally better than rural programmes. To date, however, no urban programme (in emergency or non-emergency context) has recorded coverage rates above or equal to those stipulated by SPHERE.

Coverage assessments, however, have done more than simply challenging the assumptions about access to urban programmes. More importantly, they have provided a wealth of data that sheds light on why access to urban programme is challenging, and the extent to which specific characteristics of urban environments affect coverage. The data are helping to provide the necessary evidence to debunk four of the most common urban myths about SAM-treatment services.

Urban myths about access to urban SAM-treatment services

Myth 1: Greater awareness about services and SAM in urban contexts leads to earlier presentation and improved health seeking behaviour

Access and coverage of SA -treatment services is heavily influenced by health seeking behaviour (HSB). HSB in turn is influenced by a caretaker’s understanding of the causes of SAM (aetiology) and the recognition and trust in health facilities where treatment can be found. One of the most common misconceptions about SAM treatment in urban environments is that traditional beliefs about aetiologies and corresponding HSB generally found in rural areas do not extend to urban environments. In other words, caretakers living in urban areas are thought to be able to recognise SAM as a health condition that can and should be treated in health facilities.

The experience of implementing SAM treatment programmes in urban environments, however, has helped uncover a more complex picture of HSB. In Monrovia (Liberia) and urban Maroua (Cameroon), for example, knowledge of SAM as a unique health condition has been found to be generally limited. Teenage pregnancies and the isolation of many households from the broader, inter-generational network commonly offered by rural communities were found to be compounding factors reducing awareness about the condition. Traditional Health Practitioners (THPs) are active in Monrovia, providing both preventative as well as curative services for malnutrition. There is evidence to suggest that they represent, in many cases, a first tier in HSB. Similarly, religious leaders (including Christian Pastors) also have a central role in HSB. In Kinshasa City Province (DRC), pastors are frequently consulted as a result of the stigma attached to malnutrition which discouraged cases from presenting openly at the health centre. In Kisumu (Kenya), coverage assessments have shown how cultural beliefs and practices have contributed to late presentation of SAM cases in treatment centres. Wasted and oedematous children are thought to have been bewitched and thus the services of a traditional healer are often sought first. In Port au Prince (Haiti), malnutrition signs were clearly recognised by mothers, but they were generally understood as being the signs of a natural/ mystic disease (djiok) caused by a curse or witchcraft associated with jealousy. The taboo associated with malnutrition led health staff to focus on the issue of ‘low weight’ instead of malnutrition to prevent defaulting. In spite of the large scale efforts to identify and treat malnutrition following the 2011 earthquake, continuing late presentation of SAM cases suggests limited changes to HSB. A similar lack of understanding of the causal factors and signs of malnutrition in Tadjourah town (Djibouti) meant that, although fever and diarrhoea were clearly seen as health conditions that could and should be treated in a health facility, the resulting wasting was not always perceived as needing treatment.

What these examples demonstrate is that the need to understand community perceptions, and invest in community sensitisation and active case-finding activities, is as pressing in urban environments as it is in rural areas. Many SAM treatment services, including those in Kisumu (Kenya), have recognised the need to identify and incorporate THPs into their community mobilisation activities. Programmes must recognise actual HSBs linked to SAM treatment and develop ways of adapting service delivery to reflect these.

Myth 2: Fewer facilities can deliver acceptable access and coverage in urban contexts

Geographical coverage, often defined as the proportion of health facilities in a given area offering a particular service, is key to ensuring optimal programme coverage. In rural settings, SAM treatment programmes generally aim to locate services in hard-to-reach areas, ensuring that travel times are as low as possible. In urban settings, however, higher population density and a comparatively smaller spatial area often leads to a programmatic assumption that fewer service delivery points (health centres, posts, clinics) can still deliver optimal programme coverage.

In Monrovia (Liberia), for example, a SAM treatment programme supported by ACF aimed to deliver services for the entire Greater Monrovia by using only eight out of the 250 health facilities in the city. When evaluated in 2011, the services were only reaching an estimated 24.8% of SAM cases. In Nairobi (Kenya), SAM treatment services supported by Concern Worldwide initially increased from 30 to 54 Outpatient Therapeutic Programme (OTP) sites in recognition of the need to increase service delivery points. Even then, coverage assessments showed that access was still limited, leading to a decision to double the number of sites. Today, SAM treatment services are delivered through 80 facilities.

Finding the right number of service delivery points requires a degree of advanced planning and testing. The right framework does not always involve incorporating SAM treatment services into all available facilities, and the costs associated with this may make it unfeasible. What experience has shown, however, is that successful urban SAM treatment services require networking and inter-connectedness between different facilities that can assist in the identification and referral of SAM to treatment sites. In Nairobi (Kenya), for example, the project has identified the need for children being treated by Outpatient Diseases (OPD) and Comprehensive Care Centres (CCC) in urban areas to regularly screen children’s mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) and refer SAM cases to connected facilities offering SAM treatment services. Such partnerships require collaboration and coordination between different stakeholders. In Port-au-Prince (Haiti), there were six organisations delivering SAM treatment services. A coverage assessment carried out in 2012 found poor linkages between the different non-governmental organisations (NGOs) programmes, resulting in community volunteers referring SAM cases to the health facility supported by the NGOs they were working with, instead of referring to the nearest one. The multiplicity and high turn-over of the programmes/ interventions from different NGOs in different fields was also identified to be a confusing factor for the population. Both of these factors had an impact on the collective coverage of these interventions.

Myth 3: Opportunity-costs for attending SAM-treatment services are lower in urban contexts

SAM treatment has traditionally been implemented in rural, mostly-agricultural environments in which seasonality and labour needs had a significant impact on treatment compliance and defaulting rates. It is often assumed that the absence of agricultural duties grants urban residents greater flexibility and lower opportunity costs for attending SA -treatment services.

In Nairobi and Kisumu (Kenya), however, SAM treatment services found that caregivers are time constrained making weekly OTP follow up visits a significant challenge. Like many fellow caretakers of SAM children in Monrovia (Liberia) and Port-au-Prince (Haiti), most come from lower socio-economic strata and make their living as petty traders. Their ability to attend regular, day-long SAM treatment services can represent a loss of anywhere from 16% to 20% of their weekly income. Generally speaking, the risk is even greater for those formally employed; repeated absences can result in the loss of their (rare and difficult to obtain) employment. The high opportunity costs manifest in the high defaulting rates (see above) and low compliance with referrals that are commonly recorded by SAM treatment services in urban settings. Opportunity costs for caretakers in urban contexts are equal or higher than in rural areas. SAM treatment programmes can successfully deal with this by introducing operational measures designed to reduce attendance and opportunity costs. Potential measures can include bi-weekly visits (to replace weekly attendance) and extending opening times to evenings and weekends.

Myth 4: Urban populations are static with limited or no movement or migration

The fourth and last common urban myth is that migration (short or mid-term) and population movement somehow affects urban populations less than those in rural areas. Once again, the experiences from the field tell a different story.

The population of urban slums in Nairobi and Kisumu (Kenya), for example, have been found to be very mobile. The forces that shape their movement are many, and include short-term relocation to rural areas, accidental destruction of their homes (e.g. fires) and the need to identify new credit facilities after exhausting previous ones. In Monrovia (Liberia) and urban Maroua (Cameroon), change of address and short and mid-term relocation have also been found to be very common as land-ownership is even rarer than in rural areas, and residents relocate whenever employment or housing opportunities change. In Les Cayes City (Haiti), admission from certain neighbourhoods were subject to high defaulting rates due to the dynamic populations that often move from and to the capital and rural areas. In Tadjourah (Djibouti), the start of the school holidays and the peak of the hot season result in frequent population movements from urban areas to cooler, upland, rural areas, contributing to defaulting. This migration between urban and rural areas has also been noted in other settings. In Bandundu and Kinshasa City provinces (DRC), peri-urban populations retain land for farming in rural areas or near their village of origin and family members often relocate to this land for extended periods, particularly during the planting and harvesting seasons. This mobility is vital in order for families to ensure a degree of self-sufficiency and thereby reduce expenditure on expensive foodstuffs sold in the town. In Kabul (Afghanistan), the size of the population living in informal settlements (KIS) varies depending on the season, with significant seasonal migration occurring during winter, when weather conditions deteriorate and employment opportunities decrease. During this period, families tend to migrate to the warmer eastern part of Afghanistan and to other big cities, leading to significant drops in attendance and increases in defaulting.

When migration and relocation occurs, caretakers seldom inform SAM-treatment service providers, thus preventing transfer to facilities closer to the new locations, and thus contributing to defaulting. Service providers must recognise that urban populations are not static; efforts must be made to constantly communicate to caretakers their right to be transferred to other facilities.

Conclusions

As SAM treatment services become more widely available in different contexts, new challenges will continue to emerge. The experiences of rolling out such services in urban contexts has shown that many of the underlying assumptions, or ‘urban myths’, that have traditionally shaped these interventions do not correspond to the more complex reality posed by urban populations. These urban features mean that some core elements of outpatient SAM treatment must not only be maintained (e.g. community sensitisation and case-finding), but also adapted to the specific challenges and opportunities of urban contexts. The experiences of many urban SAM treatment programmes are increasingly proving that improving access to services is not only a question of doing more (more service delivery sites, more information) but also of doing better. What is needed is the kind of participatory design that truly acknowledges the needs of the population it seeks to support. Changing attitudes about urban populations is only part of challenge to improving access to SA -treatment services. Gaining the political will to radically reshape treatment services to make them truly accessible to a complex, mobile, and often marginalised urban population remains the greatest task yet.

For more information, contact: Saul Guerrero, email: s.guerrero@actionagainsthunger.org.uk

Imported from FEX website