Barrier analysis to inform breastfeeding support in Mali

By Casie Tesfai

By Casie Tesfai

Casie Tesfai is a Nutrition Technical Advisor for the International Rescue Committee (IRC) based in New York since 2012. She has over 10 years of humanitarian nutrition field experience where she specialised in CMAM and infant and young child feeding, particularly in emergencies. She holds an MSc in Public Health Nutrition from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, a certificate in Breastfeeding Practice and Policy from the UCL Institute of Child Health and is a Certified Lactation Counsellor.

The author would like to acknowledge the contribution of the International Rescue Committee nutrition team in Mali.

Location: Mali

Location: Mali

What we know already: Sub-optimal infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices significantly contribute to under 5 deaths. There are many examples of interventions that are ineffective as they fail to address context-specific barriers to optimal breastfeeding patterns.

What this article adds: An IYCF barrier analysis tool was included as part of a scheduled SQUEAC assessment by IRC in Mali. The output comprised a matrix of recommended versus actual feeding practices; beliefs and attitudes; barriers and motivating factors. Targeted messages were drafted to incorporate into a comprehensive breastfeeding programme. Where there is staff capacity, qualitative IYCF assessment via SQUEAC is feasible and improves the chance of programme effectiveness.

Suboptimum breastfeeding results in more than 800,000 deaths of children under 5 years annually (11.6%)1. Nearly 15% of deaths of children younger than 5 years can be avoided (i.e. 1 million lives saved) if ten core nutrition interventions are scaled up2. Delivery of an infant and young child nutrition package, including breastfeeding and complementary feeding support, features in the top three interventions in the Lancet 2013 series, with an estimated potential 221,000 (135,000–293,000) lives saved3.

Strategies to promote breastfeeding in community and facility settings have shown promising bene?ts for enhancing exclusive breastfeeding rates4, yet in humanitarian contexts, breastfeeding support remains one of the least funded interventions5. Since 1996, only about 20 countries6 have made significant improvements in breastfeeding rates (more than 20 percentage points)7. The notable success factors in these countries include national government leadership, comprehensive programmes at multiple levels, engaging multiple partners and scaling-up initiatives8. Ineffective approaches, such as ‘one-off’ promotion campaigns or replication of generic messages through sensitisation or mass media9 often wrongly assume that ignorance of the benefits of breastfeeding or optimal practices are the major barrier. Effective breastfeeding programmes use evidence from barrier analysis or qualitative work to design strategies which often show that a combination of effective communication activities, skilled healthcare professionals in counselling, appropriate healthcare policies and community engagement is needed10.

This article shares field experience from the International Rescue Committee (IRC) Mali programme in using an infant and young child feeding (IYCF) barrier analysis tool as part of a Semi-Quantitative Evaluation of Access and Coverage (SQUEAC) assessment, in order to design a comprehensive breastfeeding programme. The article focuses on the assessment process.

Programme context

The IRC has been present in Mali since 2012. In nutrition, IRC supports the Ministry of Health (MoH) in the community based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) in Kati, Kalabankoro and Nara Districts (Koulikoro Region) and in Menaka District (Gao Region). As acute malnutrition in the Sahel is on the rise and Mali is undergoing a ‘triple-crisis’, 11IRC recognises the importance of intensifying efforts so that CMAM treatment (focusing on increasing coverage) is strengthened by high-impact programmes that address underlying causes of acute malnutrition, particularly IYCF.

Mali has seen exclusive breastfeeding rates increase from 8% in 199612 to 38% in 200613, however in 2012-2013, exclusive breastfeeding rates in the Southern part of the country seem to have stagnated at 33%14. It is therefore essential to ensure continuous reinforcement of breastfeeding15 practices to reduce malnutrition and save more lives in Mali.

The approach

In 2009, a resource for use in training to support integration of IYCF practices into CMAM programming was developed at an international level to meet an identified gap16. The materials comprise facilitator notes and handouts to support training of health care personnel and community health workers. A slightly modified version of the ‘Breastfeeding (and Complementary) Practices Matrix included in the resource17 has been used by the author in several countries to collect local IYCF practices, beliefs and barriers to optimal practices to inform and design IYCF programmes. The results of the matrix have been used in three ways:

- To include barriers, actual practices and beliefs in breastfeeding counselling training to ensure that participants can adequately address these barriers and beliefs by the end of the training.

- As part of an infant feeding assessment (including in emergencies) to develop an appropriate programme response.

- To develop ‘targeted’ breastfeeding messages that address local beliefs and misconceptions as part of a wider breastfeeding programme.

In the case of Mali, the adapted matrix was used as a framework to inform programme design.

Click the image below to enlarge

Methods

Data collection for the IYCF barrier analysis is qualitative and should be exhaustive and triangulated with multiple sources (e.g. men and women in the community, caretakers in the CMAM programme, health workers, community outreach workers, midwives/traditional birth attendants,) and methods (interviews, focus group discussions, semi-structured interviews and observation). As this is also a rule that applies to the SQUEAC method of assessment, IRC undertook a pilot project to assess whether it would be feasible to collect this information as part of the qualitative and routine data collection in stage one of the SQUEAC in Kati District18, Mali.

As IRC’s SQUEAC teams were larger by 1-2 persons than is normally required for a SQUEAC, it was considered that this information could be easily collected during the SQUEAC without affecting quality. However this additional element should not be included if there is any risk that the quality of the SQUEAC could be reduced. It is not essential to undertake IYCF barrier analysis as part of a SQUEAC assessment; in this instance, it was easier since the SQUEAC teams were already trained on qualitative data collection through triangulation.

The SQUEAC team used an IYCF interview guide (translated into French) to collect actual IYCF practices starting from birth until two years. This information was collected from 35 communities (representing each catchment area in Kati District, Koulikoro Region) through focus group discussions, interviews and observations with community members, health workers and caretakers of severely malnourished children, to ensure the district was covered. Data collection stopped after 35 communities had been assessed and when the SQUEAC teams were sure that saturation had been reached (no new data were uncovered).

Results

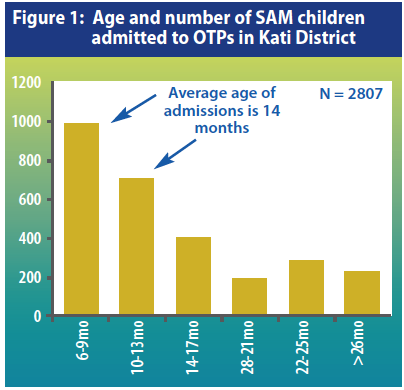

The SQUEAC team found that the average age of SAM admissions19 from the Outpatient-Therapeutic Programmes (OTP) in Kati District was 14 months (see Figure 1), which supports what we know globally about the majority of acute malnutrition starting before two years20.

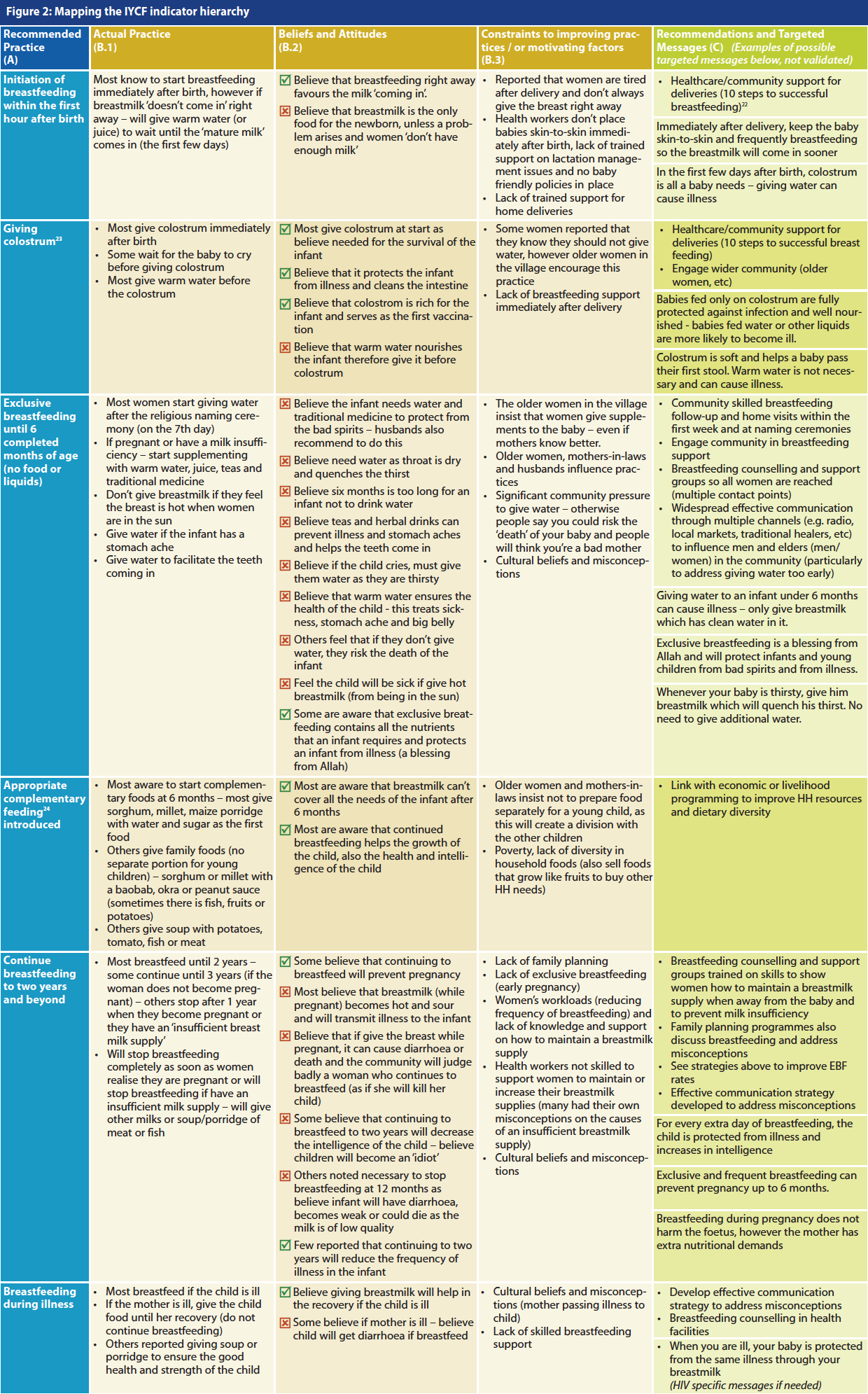

The results of the IYCF assessment are presented as a matrix which summarises actual IYCF practices in Kati District compared to each optimal recommendation, as well as cultural beliefs and barriers (see Table 1). Column A reflects optimal recommendations. Columns B1 - B3 present the results of the qualitative data collected. Column C presents the comprehensive recommendations for each stage of the continuum as well as giving space to draft a few targeted messages to address local beliefs and misconceptions. The drafted messages should go through a process of validation and translation to ensure that the intended message is easily understood by the community and part of an effective communication plan21.

The team conducting community focus group discussions with women to collect IYCF practices

The team conducting focus group discussions with men to collect IYCF practices

Discussion

Breastfeeding programmes often take the form of breastfeeding education to mothers. As reflected in the barrier analysis, women feel significant pressure from other community members to go against healthcare advice (even when women know and understand the recommendation).

Perceived or real milk insufficiency is one of the most common reasons why women abandon exclusive breastfeeding globally25 and was also noted frequently in this assessment (it was also widely misunderstood by health professionals who participated). Adequately addressing this issue requires training in lactation management, an understanding of breastfeeding physiology, counselling and the ability to take and interpret a breastfeeding history. This is just one example of one barrier that requires considerable skill which cannot be addressed through generic promotion activities (e.g. posters or replicating generic messages such as ‘Breast is Best’).

Promotion does play a role in breastfeeding programmes, however this should be part of an effective communication strategy based on a qualitative barrier assessment and ‘targeted’ messages and campaigns. These should be developed and validated to ensure they are understood by the community and should serve to complement a comprehensive breastfeeding programme26 (addressing multiple barriers at all levels). For example, the combination of 1) good delivery practices so that breastfeeding gets off to the best start immediately after birth; 2) with early post-partum follow-up (infants are supplemented with water in the first week); 3) with community breastfeeding support for when problems arise (e.g. not enough milk, pregnancy, etc); 4) with an effective communication strategy addressing misconceptions targeted at the wider community who influence women is likely to have a much larger impact27 in Mali.

Promotion does play a role in breastfeeding programmes, however this should be part of an effective communication strategy based on a qualitative barrier assessment and ‘targeted’ messages and campaigns. These should be developed and validated to ensure they are understood by the community and should serve to complement a comprehensive breastfeeding programme26 (addressing multiple barriers at all levels). For example, the combination of 1) good delivery practices so that breastfeeding gets off to the best start immediately after birth; 2) with early post-partum follow-up (infants are supplemented with water in the first week); 3) with community breastfeeding support for when problems arise (e.g. not enough milk, pregnancy, etc); 4) with an effective communication strategy addressing misconceptions targeted at the wider community who influence women is likely to have a much larger impact27 in Mali.

Women should not be the sole target for poor breastfeeding practices and not blamed for the end result of processes over which they have limited control28.

Qualitative assessments as undertaken in Mali are feasible and will improve the chance of programme effectiveness. The IRC Mali team has developed a comprehensive breastfeeding strategy from the results of their assessment and are currently seeking funding to implement recommendations.

For more information, please contact Casie Tesfai at casie.tesfai@rescue.org

1Maternal and Child Nutrition Series, Lancet, 2013. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet 2013; 382, Issue 9890, Pages 427 - 451, 3 August 2013

2Maternal and Child Nutrition Series, Lancet, 2013. Evidence-based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: what can be done and at what cost? The Lancet 2013; 382: 452–77

3Management of acute malnutrition would save an estimated 435 000 lives [range 285 000–482 000] and micronutrient supplementation could save 145 000 (30 000–216 000) lives.

4See footnote 2

5Aid for Nutrition: Can investments to scale up nutrition actions be accurately tracked? (ACF, 2012). ‘Promoting good nutritional practices, which encapsulates infant and young child feeding (IYCF) (including breastfeeding promotion) and good hygiene, received 15% of the funding for direct nutrition interventions.’

6Out of 86 developing countries with available trend data, UNICEF IYCF Programming Guide 2011.

7Infant and Young Child Feeding Programming Guide (UNICEF, 2011). Source: UNICEF database (2011).

8WHO, ‘Learning from large-scale community-based programmes to improve breastfeeding practices’, Geneva, WHO, 2008. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241597371_eng.pdf.

9See footnote 8

10See footnote 8

11The triple crisis refers to ‘i) the continued humanitarian impact of acute food insecurity and nutrition crisis of 2012; ii) the underlying chronic nature of food insecurity, malnutrition and the erosion of resilience in the region; and iii) the on-going current Mali crisis’. Sahel Regional Strategy Mid-Year Review 2013 (UNOCHA)

12Enquête Démographique et de Santé du Mali (DHS) 1996

13Enquête Démographique et de Santé du Mali (DHS) 2006

14Enquête Démographique et de Santé du Mali (DHS) 2012 -2013 Rapport Préliminaire (Due to the conflict in the North, this only includes the southern Regions of Mali)

15See footnote 8

16Integration of IYCF into CMAM. Facilitators Guide and Handouts. Oct 2009. IFE Core Group, ENN. Funded by the Global Nutrition Cluster. Available in English and French.

17See footnote 16. Handouts 1 and 2.

18Recently, Kati District was divided into two Districts (Kati and Kalanbankoro); both were included in the SQUEAC.

19Collected from patient registers in the Out-patient Therapeutic Programmes (OTPs) (Jan – May 2013), this did not include infants <6 months from the Stabilisation Centre (N=2807).

20Victora et al. Worldwide Timing of Growth Faltering: Revisiting Implications for Interventions. Pediatrics 2010

21See footnote 8

22Every facility providing maternity services for newborn infants should implement the 10 steps to successful breast-feeding. Protecting, Promoting and Supporting Breastfeeding: The Special Role of Maternity Services, a joint WHO/UNICEF statement

23Colostrum is the first yellowish breastmilk produced after birth – rich in antibodies it helps protect the baby from infection, aids the formation of good bacteria in the gut and eases the movement of the meconium. Colostrum is often referred to as the baby’s first vaccination.

24All infants should start receiving adequate foods in addition to breast milk from 6 months onwards (WHO)

25WHO/UNICEF. Increasing rates of exclusive breast-feeding: Background paper prepared for the WHO/UNICEF Technical Consultation on Infant and Young Child Feeding (WHO, Geneva, 13-17 March 2000)

26See footnote 8

2728% of infants (0-5 months) received only water and breastmilk. Mali DHS 2012-2013 Preliminary report.

28Wheeler E. To Feed or To Educate: Labelling in Targeted Nutrition Interventions. Development and Change, (1985) Vol 16; 475-483.