Designing an inter-agency multipurpose cash transfer programme in Lebanon

By Isabelle Pelly

By Isabelle Pelly

Isabelle Pelly was Save the Children’s Food Security & Livelihoods Adviser in Lebanon until September 2014, and co-chair of the Lebanon Cash Working Group. She is a specialist in food security and livelihoods, and cash transfer programming, with experience spanning programme design and management, advisory roles at field office and headquarters, programme policy, and inter-agency cash coordination.

The author is very grateful to Maureen Philippon (ECHO), Joe Collenette (Save the Children Lebanon) and Carla Lacerda (Senior inter-agency Cash Adviser in Lebanon) for their insight and support. This article is a reflection of the author’s professional experience and does not necessarily reflect the position of Save the Children more broadly.

This paper reviews the inter-agency efforts to set up a multipurpose cash assistance programme in Lebanon, as part of the response to the Syrian refugee crisis, over the last year since the onset of winter 2013/14. It highlights lessons learned through large-scale cash programming in Lebanon to date, and the necessity of high quality technical and operational design supported by responsive coordination mechanisms. The paper discusses the challenges of a transition to multipurpose unconditional (from here-on ‘multi-purpose’) and inter-agency cash programming including the cross-sectoral engagement and strong leadership required for an effective programme that works across traditional sector-based humanitarian coordination structures and sector-mandated agencies. The paper draws out key lessons for future programmes, and potential inter-agency preparedness measures to overcome coordination and technical hurdles.

Background/lessons learned from Lebanon’s winterisation cash programme

Since early 2014, the Syrian response in Lebanon has been a test-case for the establishment of an inter-agency multipurpose cash transfer programme. The design of this programme sought to build on the lessons learnt from the inter-agency ‘cash for winterisation’ programme which reached nearly 90,000 refugee households with an average of $550 throughout the winter of 2013/14. This programme relied on harmonised targeting criteria, and agreed-upon cash transfer values, intended to meet the costs of a stove per household, and monthly heating fuel for five months. The rapid operationalisation of this programme, delivered through a common ATM card across the majority of agencies involved, was a success. However, there were significant gaps in the programme design, which provided a learning platform for the design of a multipurpose cash programme for 2014 onwards and are outlined in the following section.

Firstly, whilst the delivery of the programme was harmonised, the approach was developed directly by UNHCR as lead of the non-food items (NFI) working group and lacked technical input from cash programming experts within the Lebanon Cash Working Group (CWG) (see Box 1).

BOX 1 – Lebanon Cash Working Group – Syria Regional Refugee Response

Purpose: Key forum for discussion on CTP across sectors and for design of multi-purpose unrestricted cash assistance programme

History: Established in early 2013 in response to demand by NGOs to coordinate on design of CTPs.

Participants: Up to 50 agencies (including government, UN and NGOs); core group of 10 staff from representative agencies for decision-making

Leadership: Cash Coordinator, Senior Cash adviser (jointly hosted by UNHCR & Save the Children) and rotating NGO co-lead

Frequency of meetings: Monthly (previously bi-weekly).

Weblink and resources: http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/working_group.php?Page=Country&LocationId=122&Id=66

Specifically, there was no baseline market assessment undertaken as part of the feasibility assessment for winterisation cash programming. Rather, the decision to implement the cash transfer programme was based on agency concerns related to the delivery of an in-kind or voucher response for winter, following significant operational delivery challenges (including documented fraud) with these modalities in winter 2012/13. In October 2013, the Lebanon CWG commissioned a study of the stove market to assess market availability and access to this key winter item. This report did highlight the elasticity of the stove market in Lebanon, but also warned of a considerable gap if the majority of targeted refugees chose to purchase a stove unit at the outset of winter. The risk of additional stove demand being met through imports from Syria (thus to the detriment of the Syrian market) was also emphasised. However, the timing of the report, which was released when the decision on the choice of cash as an assistance modality had already been made, and the lack of sufficient buy-in within the wider inter-agency coordination structure (particularly the NFI working group), unfortunately reduced the value of this piece of work, and the take up of its recommendations, which included monitoring of supplies and prices; and mitigating efforts including in-kind contingency stock and very strong beneficiary communication regarding the upcoming cash programme.

In parallel, the lack of technical input into programme design resulted in a cash transfer value calculated based on perceived sector-specific needs (fuel and stove cost) rather than on overall understanding of household income gaps and needs. The downfall of this approach in the Lebanon context is reflected in the inter-agency impact evaluation of the winterisation programme led by IRC2. This analysis reveals that the majority of additional cash was spent on covering gaps in food, rent and water expenditure, whilst on average only 10% of the assistance was spent on heating fuel and clothing. Almost half of the beneficiaries reported that their heating supplies were not sufficient to keep warm. This is not due to unavailability of the supplies in the market, but because beneficiary income (through labour and assistance) income is so low that they are forced to prioritise basic expenditures.

Secondly, the design of the winterisation response suffered from significant timing challenges due to a multiplicity of changes and competing priorities occurring simultaneously within the broader response. In September 2013, a targeting process for ‘regular’ food and NFI assistance was introduced, using a demographic burden score developed on the basis of the VASyR 20133 findings. This resulted in a reduction from blanket targeting to circa 70% of the registered population receiving assistance. Whilst targeting for winterisation cash assistance did build on this process (see footnote 1), it also introduced a parallel system by using different targeting criteria indicators (such as altitude), which created significant confusion for households, as well as agencies, which were ill-equipped to describe this process. The fear that households may be excluded from assistance during the often bitterly cold Lebanese winter led to an emergency ‘verification’ exercise through household visits, aiming to re-include wrongly excluded households, which further increased confusion for vulnerable households. In parallel, a significant change was made to the operational delivery of ‘regular’ food assistance, as WFP transitioned from a paper voucher to an e-voucher more or less contiguously with the roll-out of the UNHCR ATM card used for winter cash assistance. A large proportion of refugees, many of whom had never used electronic payment methods in the past, simultaneously received two cards, with very different functionalities (i.e. e-vouchers redeemed at POS at local pre-identified food shops and winter cash assistance withdrawn at ATMs), and often from two different agencies (i.e. WFP and UNHCR and their different partners). Despite significant efforts to create separate effective training and helplines to differentiate the cards this was sub-optimal from the beneficiary standpoint as well as from the perspective of value for money and operational efficiency.

Notwithstanding these challenges, the CWG was eventually able to influence the technical quality of the winterisation programme through the development and roll-out of common baseline and monitoring tools. The ATM card platform also enabled parallel other cash programmes (i.e. conditional cash for livelihoods or shelter programmes) to be delivered through the same cards, through cross-loading of cards between agencies.

The experience of this winterisation cash programme, led to a desire and willingness to (a) further harmonize cash programme design including targeting, monitoring and delivery mechanisms and (b) transition to longer-term and scale-up of multipurpose cash assistance as a strategic shift within the response. This therefore required the CWG, through the broader coordination system, to draw on these technical and operational lessons learned and retroactively apply best practices.

The focus of early 2014 was therefore oriented around: checking assumptions on the feasibility of cash assistance (particularly relating to markets and banking system functionalities); developing common objectives and the resulting monitoring framework for multipurpose cash assistance; and improving and streamlining operational design, with the objective of establishing a one-card system for the delivery of WFP food assistance and multipurpose cash assistance, rather than the two systems outlined above. This ambitious workplan was set-out by the co-leads of the Lebanon CWG in February 2014 following an ECHO-led meeting in Brussels on cash coordination in Lebanon. The challenges encountered in delivering on this workplan are detailed in the section below.

The programme design to date

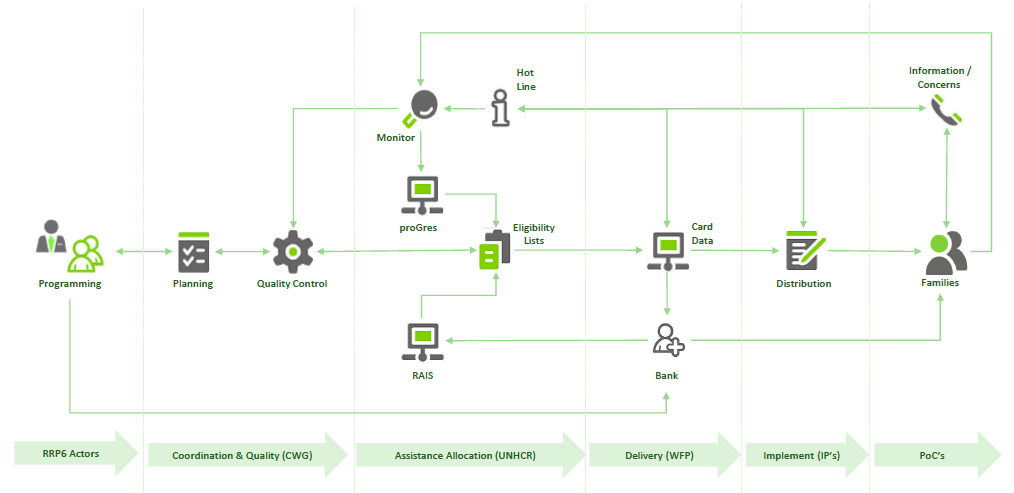

The crux of the future inter-agency programme design, building on in-country lessons to date, was defined through a consultancy led by Avenir Analytics, which set out to outline and define the optimal operational set-up for multipurpose CTP. This model aspired to build on the scale and coverage of WFP’s existing e-voucher programme (delivered through BLF bank) and use this delivery platform (through adding a separate cash ‘wallet’ to the same card), and WFP’s implementing partners, as the basis for the delivery of cash assistance. This model is visualised in Figure 1, and other key components of the programme design which evolved through multi-agency consensus are summarised in Box 2.

Box 2 : Multi-purpose inter-agency cash programme design

Key objective: To prevent the increase of negative coping mechanisms among severely vulnerable Syrian refugees during the period of cash assistance

Target population: Economically vulnerable Syrian Refugees

Targeting methodology: Proxy-Means Testing (PMT) through a pre-identification ‘bio-index’ applied to the UNHCR ProGres database, or through application of an economic vulnerability questionnaire

Target numbers: 28% of Syrian refugees identified as highly economically vulnerable (circa. 66,700 households as of June 2014), although funding shortfall is significant

Monthly cash transfer value: 175 USD per month intended to complement Monthly income to meet the Survival MEB; intention is to increase cash transfer value during the winter months

Figure 1: Recommended optimal operational set-up for CTP (Avenir Analytics report)

Challenges transitioning to multipurpose inter-agency cash programming, and lessons learned for future responses

Aspiring to a common technical and operational approach

The CWG workplan and programme design outlined above aimed to address technical and operational issues specific to Lebanon, whilst designing a robust operation that makes the process in Lebanon innovative and valuable for future cash operations. This process aspired to move away from the outdated ‘project and sector-based approach’ and promote increasing coordination, at minimum to avoid duplication and ideally to harmonise the implementation modality. In Lebanon the ambition was also to go one step further in order to give the recommendations of the CWG a binding character. This was not formalised as such, as despite best intentions, no agency proved ready to relinquish its decision making ability. Rather, good will and strong harmonisation efforts have been the driver of successful coordination outcomes as has the alignment of donors (particularly ECHO and DfID) who have proven instrumental in ensuring that the recommendations of the CWG are followed.

The Lebanon experience demonstrated that building technical consensus requires strong and legitimate expertise, leadership and ownership of the process. However, no decision is purely technical and at a certain point potential technical refinements have to cease and a decision made to go with an optimal (albeit not perfect model). Technical programme design staff need to be supported by strong management, and acknowledge the balance to be struck in a refugee operation between technical good practice, and operational reality and scale at a time of funding stagnation. As a specific example, the dialogue over the value of a monthly transfer and the number of people to be assisted was heated in Lebanon between advocates of a ‘broad but shallow’ approach contributing a minimal amount to a larger number of households versus a ‘narrow but deep’ approach ensuring survival needs were met for fewer households. Also, whilst statistically extremely robust, the targeting methodologies developed by the CWG and its ‘Targeting Task Force’ do not enable a ‘ranking’ of households within the 28% most vulnerable which makes ‘narrow’ targeting imperfect.

Recognition of multi-purpose cash assistance as a cross-sectoral modality

By definition, the multipurpose nature of the planned assistance requires coordinated engagement across traditional sector divides. Indeed, in the current context, the proposed assistance package (see Box 3) only provides a contribution towards meeting survival needs, thus leaving a gap between income and expenditure, particularly during the winter month. To date, all assistance monitoring reports for Lebanon demonstrated that the two priority expenditures are food and rent, but the exact prioritization of expenditures is not known. While there may be discussion at household level on what to spend the money on (see comments on winter assistance above), multi-purpose cash transfers must come with the acknowledgement that households will make their own choices anyway: to place the decision power with the people assisted may be the adult age of humanitarian assistance. Such an approach encourages a broader analysis of household needs from a holistic perspective, which typical coordination structures are not set up for, and risks the perception that the roles of specific sectors or institutions are being challenged. In Lebanon, a particular challenge was the convergence of the delivery of sectoral assistance towards the UN-led proposed models (WFP for food assistance; and UNHCR for NFIs), which remain relatively inflexible to changes in modality. Existing and well-documented limitations to cash coordination in the global humanitarian coordination structure4 manifested themselves again in Lebanon. This demonstrated the need to apply best practice when coordination structures are initially established, namely the distinction between strategic and technical coordination, and the need for formalised working linkages with all sector working groups and within the humanitarian coordination architecture.

BOX 3 – Calculating the transfer value OF THE the severely economically vulnerable households

Survival Minimum Expenditure Basket (SMEB): This includes the minimum food required to meet 2100KCAL/ day, the minimum NFI, rent in Informal Settlements, minimum water supply required per month. Clothes, communication and transportation are calculated based on average expenditures.

| To Calculate Proposed Cash Assistance: | $ value |

| SMEB | $435 |

| Minus midpoint of Severely Vulnerable income (using expenditure as a proxy) | $110 |

| Minus average food assistance package provided by WFP | $150 |

| TRANSFER VALUE | $175 |

In parallel, coordinated design of multi-purpose cash programming inevitably results in decisions that will affect agency sense of territoriality, particularly when there are questions of efficiency and how best to achieve economies of scale to be tackled. There are a slew of practical and political reasons why the humanitarian community may resist change. The clear recommendation from the consultancy on the optimal operational set up was to limit the number of partners possibly to the extent that in a given area WFP partners and the "cash" partner should be the same. The basic principle of fewer partners is agreed. What is not is which partners are ready to relinquish or refine their role. A striking example of this is the fact that WFP has maintained a protective approach to food by using a food voucher, which has been perceived as territorial by certain stakeholders (whilst acknowledging some of WFP’s donor constraints). Against this backdrop, WFP intends to conduct a pilot study comparing the food security outcomes of cash vs. vouchers, before making any decision on a change to a pure cash modality. This, despite inter-agency monitoring analysis demonstrating that food is prioritised at household level relative to other basic needs. Acknowledging possible resistance and the desire amongst some to retain the status quo, the donor community needs to be clear and united in demanding a refined structural response.

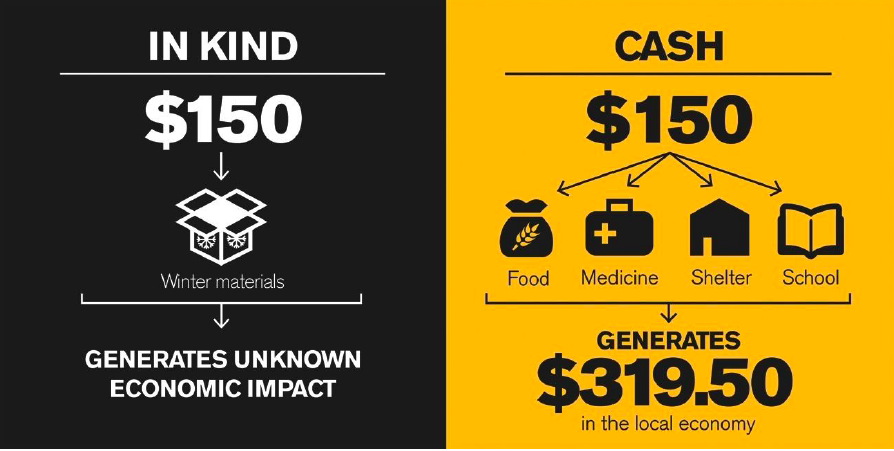

Engagement with the Government

Multipurpose cash assistance design also requires proactive and continuous engagement with pre-existing government social protection schemes, to ensure optimum harmonization on targeting and assistance value, and appropriateness relative to the socioeconomic context -minimum wage, poverty line, national safety nets, etc. In Lebanon, two particular challenges were faced - firstly, the Government of Lebanon’s (GoL) reluctance to accept the proposed Survival Minimum Expenditure Basket (SMEB) for Syrian refugees, to which multipurpose cash assistance is intended to contribute; and the value of the SMEB relative to the package of subsidized services (including education and healthcare) provided to poor Lebanese through the Ministry of Social Affairs’ National Poverty Targeting Programme (NPTP). Specific concerns of the GoL are the inequity between these forms of assistance, and institutional and political constraints in moving to a cash-based model of social protection for the Lebanese population (although WFP is partnering with the NPTP for an extension of the e-voucher programme to 5,000 Lebanese households by the end of 2014). Another concern alluded to by the GoL has been the broader economic impact of cash on Lebanese markets. IRC’s recent analysis of the multiplier effect of cash-based assistance has demonstrated that each dollar of cash assistance spent by a beneficiary household generates 2.13 dollar of GDP for the Lebanese economy; this figure is 1.51 in the food sector for the WFP e-voucher programme5. See Figure 2.

Figure 2: Multiplier effect of cash-based assistance

Need for an over-arching budget

The effectiveness of inter-agency discussions was also hindered by the absence of a dedicated planning budget for cash assistance in 2014: the idea was foreseen in the RRP6, but even where a cash modality was specified, the potential budget for multi-purpose cash assistance remained siloed under different sectoral headings, thus contributing to a projectised approach incompatible with the design of multi-purpose cash assistance. As a result, the technical and managerial decisions relating to targeting and transfer value versus scope and scale of programming, lacked direction as neither donors nor UNHCR were able to provide clarity on anticipated budgets, and resulting gaps in assistance. The principle adopted by the CWG was to advocate for an overall budget based on a package of assistance to meet the Survival MEB for all highly vulnerable households (28% of the registered refugee population), as outlined in Box 2.This amounted to over $200m for a 6 month period; but uncertainty over agency capacity to meet this gap remains significant, with UNHCR reducing their initial budget for cash assistance from $36m at the beginning of the year to $9m in June. This links to another critical budgetary issue which is the plateauing of funding for the Lebanon response in 2014 despite the ongoing increase in the number of refugees, which further lends credence to a common operational set-up designed to optimise effectiveness (see Figure 1).

Current state of progress (August 2014)

Notwithstanding the challenges outlined above, by August 2014, a critical mass of common recommendations had been produced by the CWG (as summarised in Box 2), making it almost impossible to fall back to stand alone projects: the targeting recommendations had been issued and initial beneficiary lists produced, the transfer amount agreed upon, the M&E framework designed, and clear recommendations on the optimal operational set up outlined. The fact that the CWG had laid out all these tasks early in its February 2014 workplan, supported by two meetings on multi-purpose cash assistance called by ECHO in Brussels contributed to clarity and accountability around the deliverables. Donors were interested and could use clear recommendations to make informed decisions on the relevance of the proposals received, and a number of agencies (including UNHCR) have begun implementing their cash programmes applying key elements of the common model.

Nonetheless, a few key stumbling blocks remain. The development of the targeting methodology was far more onerous and complex than expected, and as of August 2014, 2 different indices are proposed for targeting food assistance and cash assistance, which will inevitably lead to beneficiary and agency confusion with targeting, and will require additional resources to administer. Additionally, whilst in April 2014, the Avenir Analytics consultancy urged an immediate transition to a one-card system using WFP’s e-card platform (administered by BLF bank), this has still not materialised as discussions on costs and legal constraints between WFP and UNHCR have not been resolved. Whilst M&E tools based on the common framework are under development, these remain to be rolled out across agencies, and the central analysis function has not yet been defined.

Evolving role of Cash Working Group

The role of the CWG has continuously evolved alongside the technical and operational discussions outlined above. In response to the need for strong leadership and decision-making, a core group (including UN, NGO and government representatives) was elected. The group has consistently drawn from the resources developed by CaLP around documenting Cash Coordination best practices globally. In addition, a senior cash advisor position was created under the inter-agency coordinator in an attempt to provide strategic oversight on the use of cash assistance across the response. The elected core group is tasked with making recommendations either through consensus or by a majority vote. Time will tell whether this proves to be a relevant model for effective and accountable decision-making, and its applicability in other contexts. At present donors are not part of this core group, but this may need to be revisited at a later date. In Lebanon, donors have consistently been pressed to align with and enforce CWG recommendations. DfID and ECHO in particular have been very engaged in supporting key decisions, and then feeding to the wider donor group. This coordination implies a need for a more strategic and transparent inclusion of donors.

Conclusions and recommendations for future multi-agency processes

Based on the ongoing challenges detailed here, fundamental lessons have emerged for applicability to future humanitarian contexts. Implementing a multi-purpose cash assistance programme inevitably implies agencies, donors and governments relinquishing control over the use of cash assistance at household level. This fact continues to create discomfort at agency level, and in engaging with governments, particularly in a refugee setting. Hence, as with all significant changes in the role and perception of cash assistance globally, robust M&E and impact evaluations (such as that led by IRC6) will continue to be necessary to demonstrate the effectiveness of cash assistance as a means of holistically addressing household needs. An over-arching technical take-away is the need for strong decision-making on divisive and debatable issues including targeting and transfer value, as these ultimately need to be judgement calls based on best evidence, not a perfect science.

The successful design and set-up of a multi-purpose/ sector cash assistance programme across agencies requires a radical change in the existing sectoral and agency-based structure that defines the majority of current humanitarian responses. While the Transformative Agenda, World Humanitarian Summit and Level 3 triggers have signalled a significant shift in this direction, more efforts need to be made to ensure that accountability, targeting frameworks and holistic approaches are prioritized for resources and coordination above sectoral divides. Until this approach becomes widespread, exemplary leadership and vision is required at individual agency managerial level, as well as through the UN-led coordination structures, optimally through an empowered CWG.

The Lebanon multipurpose cash assistance programme design has highlighted some of the broader political constraints in applying such leadership and direction, as well as the critical role donors can play in driving decision-making on issues as contentious as cash assistance. In due course, effective programming may be exemplified by one agency leading on delivery of cash assistance across a response. Whilst this may be operationally optimal, a formal set-up needs to anticipate the operational and legal challenges (including traceability of funds and reporting requirements) of inter-agency cash transfer programmes, i.e. through pre-agreed HQ-level framework agreements. Another way of conceptualising such a model is to envisage a distinct role for individual agencies in the overall design, implementation and monitoring of a cash assistance programme, building on agencies’ unique strengths - NGO consortia are a prime example of such a set-up, and one which may be used to optimise the delivery of cash assistance in Lebanon in 2015.

For more information, contact Isabelle Pelly, email: Isabelle.pelly@savethechildren.org or i.pelly@savethechildren.org.uk ; +44781 514 6504

Postscript

By UNHCR Lebanon and UNHCR Cash Section, Division of Programme Support and Management, Geneva

UNHCR is fully behind the move toward adapting its assistance to the specific needs of refugees and other persons of concerns, hence its preference for multi-purpose grants where appropriate and feasible. We are greatly appreciative of the effort the author has made to describe the process and lessons learned from winterisation assistance in Lebanon (2013-2014) and subsequent efforts to operationalise a multipurpose grant programme which started in August 2014. However we also feel that the topic is too important not to get right. First of all, the winterisation programme was not an unconditional or multipurpose grant meant to compensate for shortfalls in minimum expenditures. It was a grant designed for the purpose of winterisation - to keep people warm. Two evaluations (both on implementation and on impact) have been completed and will inform the design of the 2014-2015 winterisation assistance programme. In relation to multi-purpose cash programming, the operational constraints in general, and specifically in Lebanon, are complex and deserve thorough analysis. The ECHO Enhanced Response Capacity grant (2014-2015) and the careful consolidation of learning foreseen in the grant, will be used by UNHCR and partners to this end. UNHCR remains committed to working with partners in Lebanon to ensure the best possible platform for cash programming, enabling gains in providing effective and efficient humanitarian assistance.

1 1) Targeted families that had been found eligible for assistance as part of the overall targeting exercise conducted by UNHCR and WFP and living 500m above sea level; 2) Families (registered and unregistered refugees, and Lebanese) living in informal tented settlements (ITS) and unfinished buildings.

2 See article by IRC Lebanon on the evaluation of the Lebanon winteristation programme.

3 Vulnerability Assessment of Syrian Refugees: http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/download.php?id=3853.

4 CaLP, Comparative study of cash coordination Mechanisms, June 2012, and Fit for the Future – Cash Coordination, May 2014

5WFP Economic Impact Study: Direct and Indirect effects of the WFP value-based food voucher programme in Lebanon. August 2014

6 See article summarising the evaluation of the IRC programme in this edition of Field Exchange