Emerging cases of malnutrition amongst IDPs in Tal Abyad district, Syria

By Maartje Hoetjes, Wendy Rhymer, Lea Matasci-Phelippeau, Saskia van der Kam

By Maartje Hoetjes, Wendy Rhymer, Lea Matasci-Phelippeau, Saskia van der Kam

Maartje Hoetjes is a Medical member of the MSF emergency team, currently working in South Sudan. She worked as Medical Coordinator in Syria from February to November 2013.

Wendy Rhymer started working with MSFOCA in 2007 as a nurse/midwife and was MSF medical coordinator for Northern Syria from December 2013 to May 2014. Wendy was interviewed by the ENN in early May 2014.

Lea Matasci-Phelippeau is a psychologist and worked in Syria as a mental health officer. He is currently working as Mental Health Officer in South Kivu, Democratic republic of the Congo, for MSF OCA.

Saskia van der Kam is the nutrition expert of MSF in Amsterdam.

Saskia van der Kam is the nutrition expert of MSF in Amsterdam.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the work of Médecins Sans Frontières Operational Centre in Amsterdam (MSF OCA), the team MSF OCA in Syria and Vanessa Cramond, Emergency Manager (Medical) at the Emergency Support Desk at MSF OCA.

Sections of this publication are part of Maartje Hoetjes’ dissertation for a Masters in International Health1.

Pre-war food and nutrition situation

Al-Raqqah governorate is in the North of Syria and has Al-Raqqah city as its capital. The governorate is divided into the three districts of Tal-Abyad, Al-Tawrah and Al-Raqqah. Tal-Abyad district was estimated to have around 200,000 inhabitants, of which around 40,000 were internally displaced populations (IDPs) (March 2013). There are no official collective centres or camps in Tal Abyad district. The IDPs live with host families or in empty buildings or makeshift accommodation with limited protection from weather conditions.

Pre-war, before March 2011, the main economic activity in Al-Raqqah governorate was agriculture, with the Euphrates as an important source of water for irrigation2,3. In combination with imports from neighbouring countries, food availability generally met the needs of the growing population. With fixed price policies from the government, staple food was accessible for all. The agricultural sector was hit hard by the water crisis that peaked in 2008, which increased unemployment and reduced local food production. The event coincided with external economic factors and neo-liberalisation policies driving up prices of food, fertilisers and energy. These developments caused many Al-Raqqah farmers to move from their lands to the southern cities, in the hope of finding a job4,5,6.

Pre-war, before March 2011, the main economic activity in Al-Raqqah governorate was agriculture, with the Euphrates as an important source of water for irrigation2,3. In combination with imports from neighbouring countries, food availability generally met the needs of the growing population. With fixed price policies from the government, staple food was accessible for all. The agricultural sector was hit hard by the water crisis that peaked in 2008, which increased unemployment and reduced local food production. The event coincided with external economic factors and neo-liberalisation policies driving up prices of food, fertilisers and energy. These developments caused many Al-Raqqah farmers to move from their lands to the southern cities, in the hope of finding a job4,5,6.

Undernutrition was a problem in pre-war Syria, reflected in 9.7% of children under five years underweight for their age, 2.3% wasted7 and 29% stunted8. Underweight and wasting were reported to be more prevalent in Al-Raqqah governorate, with the 6-11 months age group mostly affected9. In Al-Raqqah governorate, there were no specific protocols or programmes in place for the treatment of moderate and severe acute malnutrition. Since the outbreak of the conflict, agricultural production has been further hampered by insecurity limiting access to fields and markets, as well as the high price of fuel10. Moreover, the region experienced damage to its irrigation canals (10%)11. Shortages of food, due to limited production as well as import problems, have been regularly reported and the prices of bread and other food have significantly increased12.

Undernutrition was a problem in pre-war Syria, reflected in 9.7% of children under five years underweight for their age, 2.3% wasted7 and 29% stunted8. Underweight and wasting were reported to be more prevalent in Al-Raqqah governorate, with the 6-11 months age group mostly affected9. In Al-Raqqah governorate, there were no specific protocols or programmes in place for the treatment of moderate and severe acute malnutrition. Since the outbreak of the conflict, agricultural production has been further hampered by insecurity limiting access to fields and markets, as well as the high price of fuel10. Moreover, the region experienced damage to its irrigation canals (10%)11. Shortages of food, due to limited production as well as import problems, have been regularly reported and the prices of bread and other food have significantly increased12.

MSF operations in Northern Syria

Médecins Sans Frontières Operational Centre Amsterdam (MSF OCA) has been working in Northern Syria, Al-RAqqah governorate, Tal-Abyad district, since February, 2013. Medical programmes include inpatient paediatrics as well as general outpatient services for adults and children. Services also include antenatal care, postnatal care, sexual and gender based violence care, family planning, as well as routine immunisation. The mental health programme includes individual and group counselling sessions, psycho-educational sessions and outpatient psychiatric care. The nutrition programme includes inpatient therapeutic feeding and ambulatory therapeutic feeding care. Expanded Programme of Immunisation (EPI) support has been provided to outlying villages. Donations of emergency medicines and medical supplies to other facilities in the surrounding area are also provided.

Médecins Sans Frontières Operational Centre Amsterdam (MSF OCA) has been working in Northern Syria, Al-RAqqah governorate, Tal-Abyad district, since February, 2013. Medical programmes include inpatient paediatrics as well as general outpatient services for adults and children. Services also include antenatal care, postnatal care, sexual and gender based violence care, family planning, as well as routine immunisation. The mental health programme includes individual and group counselling sessions, psycho-educational sessions and outpatient psychiatric care. The nutrition programme includes inpatient therapeutic feeding and ambulatory therapeutic feeding care. Expanded Programme of Immunisation (EPI) support has been provided to outlying villages. Donations of emergency medicines and medical supplies to other facilities in the surrounding area are also provided.

Until May 2014, the expatriate team included two Medical Doctors, two Nurses, a Mental Health Officer, a WASH (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene) officer, a Project Coordinator and a Logistician. To this date, 78 Syrian national staff were working with MSF, either directly or through a partnership with the national hospital in both medical and non-medical positons. When MSF OCA first began working in Northern Syria, the expatriate staff were able to live and work alongside the national staff. In January, 2014, with significant changes in the leadership of the area, a major security incident and closure of the border crossing from Turkey into Syria, MSF withdrew expatriate staff from Syria and switched to a remote management style of working. National staff were then supported by expatriate staff in Turkey via phone, email and skype. With regards to the nutrition programme, this meant that with each admission, the Syrian medical doctor would call the expat medical doctor responsible and discuss the patient’s condition and treatment plan. These patients were followed up by the expat daily, via phone calls with the on duty physician. Trainings for national staff doctors and nurses were conducted via emailed power point and skype, and proved to be successful even with this unusual method of management. In May 2014, MSF closed the programme completely (see discussion for more details).

Nutrition situation 2013

In March 2013, an exploratory mission by MSF found no cases of acute malnutrition. Two months later, in May 2013, a mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) screening was included as part of a measles vaccination campaign (including children from 9 months old to five years). This was undertaken to update information on the nutritional status of the IDP community given their situation (displacement, lack of income), a recent measles outbreak and anecdotal reports that mothers had difficulties finding appropriate food (infant formula) for their children.

The MUAC screening found a 0.6% prevalence of global acute malnutrition (GAM). Thirty eight cases (0.1%) of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) were identified amongst 34,997 children screened (see Table 1). The vast majority of the identified cases were children younger than 1 year of age. The highest numbers and percentages of malnourished were found in the Central area, with the majority in Tal Abyad town. In the city, the malnourished cases were clustered. Percentages of children with a MUAC <125mm ranged from 0-10% per area in the city. The most common explanation for malnourished children with no underlying medical issues was that caregivers had no money to purchase infant formula. Seven medical cases were children with “a hole in the heart” (a congenital heart defect). MUAC screening by mobile clinics was also used as a way of monitoring the trend in the population. This showed no increase in malnutrition (see Table 2). MUAC screening from July to September 2013 of children attending the inpatient clinic did not show an alarming number of malnourished (Table 3).

| Table 1: MUAC screening during vaccination campaign, May, 2013, Tal Abyad district, Syria | |||||

|

MUAC |

<115 mm |

115-<125 mm |

125-<135mm |

>135 mm |

Total |

|

Number |

38 | 180 |

1,161 |

33,618 |

34,997 |

| % |

0.1% |

0.5% |

3.3% |

96.1% |

100% |

| Table 2: MUAC screening in mobile clinics, 3rd August - 21st September, 2013 | |||||

|

MUAC |

<115 mm |

115-<125 mm |

125-<135mm |

>135 mm |

Total |

|

Number |

3 | 2 |

29 |

637 |

671 |

| % |

0.4% |

0.3% |

4.3% |

94.9% |

100% |

| Table 3: MUAC screening in inpatient clinics, 1st July -15th September, 2013 | |||||

|

MUAC |

<115 mm |

115-<125 mm |

125-<135mm |

>135 mm |

Total |

|

Number |

16 | 8 |

22 |

383 |

429 |

| % |

3.7% |

1.9% |

5.1% |

89.3% |

100% |

Despite the low number of malnourished cases identified in the vaccination campaign, an increasing number of malnourished cases were attending in the mobile clinics in between April and May 2013. This triggered the opening of an Ambulatory Therapeutic Feeding programme (ATFP) at the end of May 2013, followed by an Intensive Therapeutic Feeding Centre (ITFC, inpatient facility) at the beginning of July 2013. Since the start of the programme, the number of admissions has increased slightly week by week. In order to have a better picture of the factors affecting the nutritional status amongst the Tal-Abyad population, MSF undertook a small qualitative survey among the most vulnerable populations in the Tal-Abyad region of Syria in August 2013.

Qualitative survey

The surveyed population was IDPs living in schools in the Tal Abyad region13. A total of 39 persons were interviewed, all women, about their living circumstances and food security. The data were collected using a questionnaire administered by MSF staff working with the mobile clinics. The data covered a period between mid-August and mid-September 2013.

Family composition

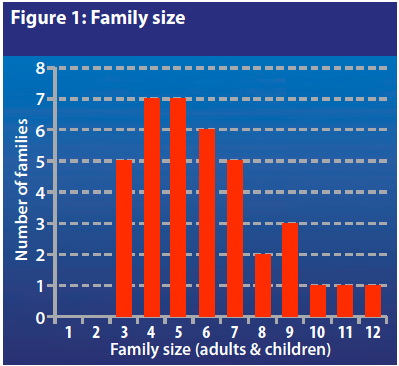

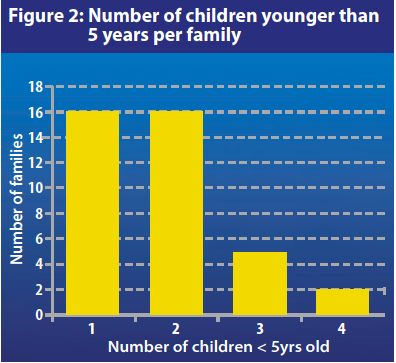

Figure 1 shows the family size amongst those surveyed. The average family size was 5.9 with 79% (n=30) having 3-7 family members. The majority of the families (84% (n=32)) had one or two children aged 5 years or under (see Figure 2). Twenty two families (58%) had one or more children younger than 12 months (one family had two children under this age).

Availability and access to food

All but one interviewed woman (n=38/39) reported that a wide range of food was still accessible at local markets. However, for some of the women (n=9), access to markets was not easy since they live 10-15 km away. Public transportation is expensive (100 Syrian Pounds); most walk long distances to reach the market, sometimes arriving too late to find the items they need as the market starts early in the morning. Culturally, men are supposed to do the shopping. Only women with ‘special circumstances’ (widows, divorced) are ‘allowed’ to go out shopping. Married women should not leave the house regularly. Those interviewed reported the major problem affecting people's nutrition is that prices continue to rise and there is a lack of money due to unemployment (see Table 4). This has a direct influence both on the quantity and quality of food that can be purchased.

| Table 4: Average price increase between pre-war and August 2013 | |

| Food |

Average price increase % |

|

Bread |

+ 233 % |

| Oil |

+ 294 % |

|

Flour |

+ 424 % |

|

Milk |

+ 424 % |

| Rice |

+ 639 % |

Almost 100% of the respondents reported having received at least one donation of food and non-food items (NFI) from different actors (Turkish Red Crescent (TRC), Qatari Red Crescent (QRC), Saudi Arabia, local court, private donations). Most of them, however, stressed that donations occur sporadically and they need regular donations. Mothers spontaneously expressed fears for their children, in particular lack of fresh milk, since this item is never included in food donations. Infant formula milk is generally available but the prices are very high; mothers simply cannot afford it. The only item that was received on a regular basis by IDPs living in some of the schools was free bread, donated by different armed groups. IDPs living in one of the schools reported receiving free rice regularly.

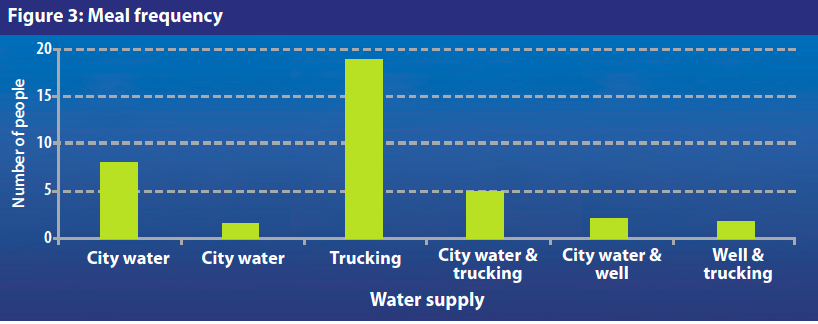

Meal frequency

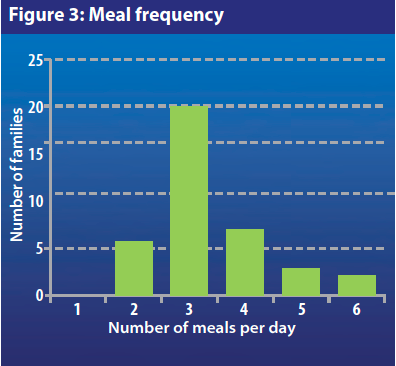

Before the war, Syrians used to have three meals per day (breakfast, lunch and dinner). The survey investigated the number of meals IDPs are currently eating each day. As Figure 3 shows, 52% of the women interviewed (n=20/38) reported that their families are having the usual number of meals, 16% are having only two meals (n=6/38) and one third of the families are eating more than three meals (n=12/38) per day. In response to the question “do you often feel hungry?” almost 75% (n=29/39) of those interviewed replied “yes”. Unfortunately, meal quantity could not be ascertained. However, since three-quarters of respondents reported often feeling hungry, it can be inferred that those who are still having three meals (or more) are actually eating smaller quantities of food.

Diet diversification

In Syria, all the family usually eat together, unless there are guests or in the case of a special event, when women and children eat separately. The diet pre-crisis was varied and mainly composed of grains (bread, rice, bulgur, etc.), vegetables (soup, salads, etc.), beans (chick peas in hummus and falafel, lentil soup, etc.), dairy products (yoghurt, milk, cheese) meat and eggs. The survey revealed that people’s current daily diet is generally composed of grains (bread, spaghetti, rarely rice) and vegetables (73% of adults, 63% of children). Only two people reported eating dairy products (milk, yoghurt). Meat and eggs are scarce and not consumed but beans and lentils are part of the diet. For some IDPs, the variety of food is even more limited; seven people reported that adults are only eating grains, with five people saying that the same is true for their children. In some cases, adults are favouring their children (n=6/33), by giving them the available vegetables and/or milk. In a small number of cases (4/33) the opposite is true, and parents report eating more vegetables than their children.

Infant nutrition and breastfeeding practices

“ And mothers should breastfeed their children two complete years for those who want the breastfeeding to be complete” (Qu'ran, 2nd verse, Al Bqarah, 233:37)

Breastfeeding is a practice accepted and even promoted by the holy Qu'ran. In fact, in “Islamic instruction, mothers are entitled a monthly payment from their husbands to breastfeed their children”. Breastfeeding was also used sometimes as a social regulator; if a mother breastfed another baby in addition to her own baby, they would become “brothers of milk”. Marriage would therefore be forbidden between the two children in later life in a culture where intra-familial marriages are still common. Also, according to custom, the parents of a woman who has been breastfed can ask for a larger dowry than if she was not breastfed.

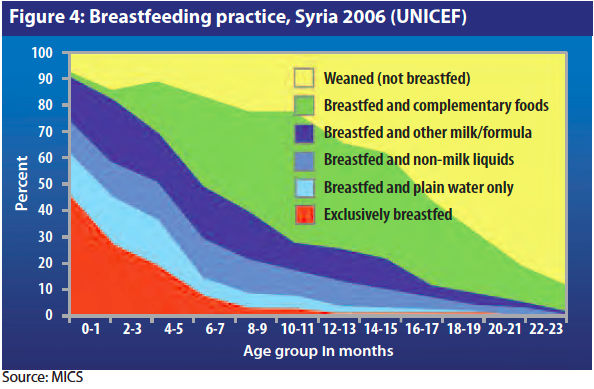

However, according to national staff, using formula milk became the new “fashion” in pre-war Syria. There are several possible ‘cultural’ reasons for this: people started to think that formula milk was better than mother’s milk, some (urban) women started to have concerns about preserving the beauty of their breasts and men who refused formula milk for their wives felt they might be perceived as mean. All these factors have meant that duration of breastfeeding has been decreasing and that some mothers have not breastfed at all. Furthermore, Syrian mothers also believe that babies benefit from water, water and sugar, a local type of “sheep clear butter”, or tea in addition to breastmilk. Exclusive breastfeeding was and is still far from being a generalised practice. These findings are supported by a UNICEF survey which showed that less than half of infants were exclusively breastfed at birth in 2006; in Al-Raqqah, the exclusive breastfeeding rates was estimated even lower, only 26.5%.

In the past decade, many efforts were made by the Ministry of Health (MoH), in collaboration with UNICEF, to provide breastfeeding education and promote exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months. According to data collected by UNICEF, from 2007 to 2011, 43% of women exclusively breastfeed during the first 6 months, and 25% continued partial breastfeeding until their baby was 2 years old. According to the data collected in the MSF survey, 68% (n=26/38) of the women interviewed reported that they were currently breastfeeding. Among them, 20 had babies aged < 12 months and four of them reported exclusively breastfeeding. When asked if infant formula was available, only three mothers replied affirmatively. For the majority of women, infant formula had become too expensive.

Health and sanitation

Lack of access to good quality water was the second most common complaint amongst respondents after lack of access to food. The surveyed IDPs got their water supply from three different sources: city water (tap), water trucking, and wells (See Figure 5). Out of the 39 people interviewed, 49% (n=19) complained about water quality, mainly saying that it is “bad”, “dirty” or “salty”. Only one respondent complained that there was “not enough” water. Despite this, only 3/39 stated that they were boiling water. Lack of fuel was a main reason for this. The third most common complaint (7 people mentioned it) was poor hygiene due to overcrowding. Hygiene supplies were included in donations but again, this happened too sporadically.

These findings support observations during the assessments in the IDP collective centres in June/July 2013 where the MSF team concluded that the IDPs living there suffer from skin diseases, such as scabies, lice and ringworm. Furthermore, 80% of the IDPs interviewed reported suffering from diarrhoea, due to bad hygiene and water quality. Following the findings of the June/July 2013 assessment, MSF launched a water and sanitation intervention in the most affected schools and started up mobile clinics targeting the collective centres.

Nutrition programme

Doctors and nurses in Syria have not been trained on how to diagnose and treat malnutrition and protocols and guidelines were not in place to support the medical practitioners, as malnutrition was not common. This gap in medical care was one of the reasons for MSF to intervene given the cases of malnutrition identified in the MUAC screening. MSF began by integrating Ambulatory Therapeutic Feeding Centre (ATFC) services into outpatient clinic activities at the beginning of June 2013. MSF also supported an ITFC in the paediatric ward in Tal Abyad hospital from July 2013. Out of an estimated under 5 population of 30,000 in Tal Abyad, the team expected 10-15 admissions per month for complicated SAM (0.5%).

Doctors and nurses in Syria have not been trained on how to diagnose and treat malnutrition and protocols and guidelines were not in place to support the medical practitioners, as malnutrition was not common. This gap in medical care was one of the reasons for MSF to intervene given the cases of malnutrition identified in the MUAC screening. MSF began by integrating Ambulatory Therapeutic Feeding Centre (ATFC) services into outpatient clinic activities at the beginning of June 2013. MSF also supported an ITFC in the paediatric ward in Tal Abyad hospital from July 2013. Out of an estimated under 5 population of 30,000 in Tal Abyad, the team expected 10-15 admissions per month for complicated SAM (0.5%).

Between July 2013 and April 2014, malnutrition was the principal reason for 5.3% of all admissions in the in-patient paediatric ward. In the same period, SAM was the main cause of mortality (21%) in the ward, followed by respiratory tract infection (RTI) and accidental intoxication (drinking petrol, cleaning solutions) (both 10.5%). All deaths due to malnutrition occurred amongst infants under 6 months. This does show an important trend compared with the mortality profile before the conflict, when malnutrition did not appear in the under-five’s mortality profile.

All patients under 5 years, presenting to either the paediatric inpatient facility or the outpatient facility, are screened for malnutrition. Children whose MUAC is below135 mm are assessed using weight-for-height z score (WHZ). All children are also assessed for oedema. Any child with WHZ <-3 or oedema is admitted. Patients are admitted to the inpatient ward (which is within the paediatric inpatient facility in the national hospital) and a caregiver is present from admission to discharge. Usually this caregiver is the mother, although sometimes an alternative female family member is designated to stay. MSF ITFC nutritional guidelines are followed, which include the use of F-100, F-75 and Ready to use Therapeutic Food (Plumpy’nut) as needed. In the ATFC, patients are seen and assessed by the nutrition nurse in the outpatient department on a weekly or bimonthly basis, depending on the condition of the patient.

To date, the majority (75%) of cases have been direct admissions to the inpatient feeding programme. Between July and December 2013, 70 children were admitted to the ITFC of whom 36% (n=25) were younger than 6 months. From January to April 2014, 49 patients were admitted to the ITFC of which 59% were younger than 6 months. This indicates that the malnutrition was a larger problem in Tal Abyad district than could have been expected based on surveillance data, which does not include this age-group. According to the ITFC medical staff, the majority of the children included in the programme were infants < 12 months. The team identified a number of contributing factors to malnutrition in these infants: a low rate of exclusive breastfeeding, significant use of infant formula in recent years, escalating prices and decreased availability of infant formula and inappropriate feeding (e.g. use of animal milk ) when infant formula unavailable. MSF market surveys showed a tremendous increase in prices of infant formula, from a pre-conflict price per can of 300SYP to 1500SYP in September 2013 and 1700SYP in February, 2014; more than a 500% increase.

Programming challenges

At the outset, there was some resistance from the doctors and nurses to follow the MSF nutrition protocols. As these staff members had limited or no experience with malnutrition, there was a belief that the patient was sick due to other reasons, and therefore only needed interventions such as intravenous fluids and antibiotics. But with training, we were able to change this to a certain extent.

All issues related to breastfeeding and re-lactation were a challenge, in particular:

- Given the culture of using infant formula, knowledge of breastfeeding among staff and patients was very low. Some mothers had not breastfed at all or had stopped two or three months ago, although their children were still under the age of 6 months. In this age group, the options for therapeutic feeding include breastmilk, therapeutic milk and infant formula. Relactation is a difficult process, even with experienced health professionals providing advice and support, and mothers who are committed to the process. As exclusive breastfeeding was not a common practice amongst most women and the staff, there was limited drive to persist with relactation.

- When these children reached their target weights and were ready for discharge, the problem presented that many of the mothers had not yet achieved exclusive breastfeeding and therefore would need to resort to giving infant formula. In ATFP where children are followed up after having been treated in the inpatient ward, MSF only provides breastfeeding advice and support, and does not give a supply of infant formula following the general international policy. This left many families in the difficult position of again trying to acquire infant formula, as no other local or international non-governmental organisation in the area was providing this to patients. The motivation to come to the ATFC for follow up was low as nothing other than advice was provided.

- Occasionally infant formula was supplied through ATFC, but the team saw this as an exception. If mothers thought that they could receive formula milk, it would have undermined all the hard work that was done in the ITFC to motivate mothers to stimulate and restart breastfeeding. Moreover, the fear was that MSF would be overrun by mothers requesting infant formula.

- The time that expats were on-the ground was not sufficient to train staff fully on breastfeeding promotion, and remote support to breastfeeding was a challenge as locally there was virtually no experienced person on the ground. Predominantly male staff were unable to give breastfeeding support, as only female staff are able to discuss and assist patients with breastfeeding. Most of the female staff had never breastfed before. Also midwives had minimal experience teaching patients about breastfeeding.

- Although many breastfeeding videos were available, as well as pamphlets/books, due to cultural considerations, these materials were deemed too sensitive to use with patients in the programme although some were useful to train the national staff. A training plan was developed with the help of an experienced Save the Children staff but the security situation prevented implementation.

The supply of therapeutic foods and items was problematic. It was difficult for agencies to access international supplies of these foods and agencies were unable to procure comparable nutritional supplies locally. There was a rupture in the supply of F100 milk in January, 2014 so that MSF was required to purchase infant formula locally as an interim measure to use in therapeutic feeding programmes.

Finally, the defaulter rate of the therapeutic feeding programme was high (30% to 50% of the exits) both for the inpatient and outpatient programmes. Some of the reasons for default are not unusual for a feeding programme; these included the fact that some of the patients were IDPs, and their families were moving to another location and that sometimes the caregiver was unable to stay with the patient in the hospital, due to other responsibilities at home. However, what was reported most commonly with regard to patient default was that the parents did not understand or value the care being provided to their children. Due to a lack of understanding of malnutrition, there was distrust that therapeutic milk would be sufficient to support these patients. Also, once patients under 6 months were transferred from the ITFC to the ATFC and no longer were being given therapeutic milk or infant formula, mothers questioned the need to come weekly for weight and physical assessment.

Discussion

Despite difficulties in active case finding and screening, the number of acutely malnourished was higher than expected. The initial assessment and the surveillance did not indicate the importance of malnutrition in the Syrian IDP and host community. This can be partly explained by the large proportion of infants younger than 6 months amongst admissions, as these generally are excluded from screening and community assessment.

Despite difficulties in active case finding and screening, the number of acutely malnourished was higher than expected. The initial assessment and the surveillance did not indicate the importance of malnutrition in the Syrian IDP and host community. This can be partly explained by the large proportion of infants younger than 6 months amongst admissions, as these generally are excluded from screening and community assessment.

Reasons for acute malnutrition in infants appear to be a low rate of breastfeeding, lack of clean water, lack of resources to buy infant formula milk and physical exhaustion of the mother. Treatment of malnourished infants works in the short term, but after discharge from the inpatient ward, a dilemma arises. MSF did not supply infant formula for use at home, but the families would face the same difficulties with feeding their babies as an alternative referral or support system was lacking. MSF actively lobbied other agencies for such support but none was forthcoming. Overall MSF recognised the importance of breastfeeding in these circumstances and organised breastfeeding promotion and individual support as much as possible given the challenging circumstances.

Despite concerns about the general food security, this did not manifest itself in the nutritional state of older children or the general population. However, it was quite visible in very young age groups, who need high quality foods, including a source of milk or other foods of animal origin.

As food security and dietary diversity is low and there are no signs of improvement, MSF considered blanket selective feeding for all children, as well as improving hospital food and lobbying for more food aid and humanitarian support. However two major constraints hampered implementation of these activities. Tal-Abyad is situated in a rebel controlled area in the north of Syria. This meant denial of regular cross-line support through UN coordinated food aid or nutritional support as this needed government permission. Importation of foods by MSF was not straightforward either. Furthermore, a significant security event involving MSF staff meant that expatriate staff were physically withdrawn from Syria in February 2014; this meant that new programme elements, like the roll out of breastfeeding promotion and support, could not be properly implemented.

Conclusions and recommendations

The Syrian context is relatively new for MSF, therefore we would like to share some lessons learned. In the immediate term, to address the needs and challenges we have identified, we consider that:

- There is an urgent need for unrestricted access to people in need throughout Syria and unhindered cross border activities.

- Nutrition assessment and surveillance systems should include infants younger than 6 months, and be alert to potential changes in the under one year age group.

- There is an urgent need to supply infant formula to babies whose mothers have not been breastfeeding and therefore have a limited or lack of milk supply, and who are unable to afford or find infant formula for their babies.

- Medical professionals should be trained on breastfeeding to help educate pregnant women and to provide skilled support to establish breastfeeding and overcome difficulties. There is a need to explore the use of medications to assist women in increasing their milk supply. Strengthened individual support should be complemented by a breastfeeding community awareness campaign focusing on the need to breastfeed exclusively for the first 6 months of age, targeting not only mothers but their families and the community.

- Management of acute malnutrition (likely requiring training), vaccination and targeting the top three illnesses should be integrated into normal paediatric health care structures.

- Blanket selective feeding programmes providing high quality foods to young children and PLW and better quality general food distributions could prevent further deterioration of the nutritional status.

The MSF programme in Tal Abyad has been closed since May 2014; leaving very few agencies addressing malnutrition in Northern Syria. There is an urgent need for others to secure access and step up their nutrition support activities in Northern Syria.

For more information, contact: Maartje Hoetjes, email: Maartje.Hoetjes@oca.msf.org

1 Hoetjes, M. The impact of armed conflict on health in Al-Raqqah governate, Syria. KIT/Royal Tropical Institute: August 2014

2 Masri A (2006) Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profiles. Rome.

3 Goodbody S, del Re F, Sanogo I, Segura BP (2013) FAO/WFP crop and food security assessment mission to the Syrian Arab Republic. Damascus.

4 Nasser, R; Mehchy, Z; Ismail AK (2013) Socioeconomic roots and impact of the Syrian crisis. Damascus.

5 International Crisis Group (2011) Popular protest in North Africa and the Middle East (IV): the Syrian people’s slow motion revolution. Brussels/Damascus.

6 Rifat H, Ismail KA, Nawar AH (2010) Syrian Arab Republic Third National MDGs Progress Report. Damascus.

7 Wasted defined as acutely malnourished with weight-for-height < -2Z-score. This includes moderate (MAM) and severe acute malnutrition (SAM)).

8 Stunting defined as Height-for-Age < -2Z-score

9 UNICEF (2008) Syrian Arab Republic Multi Indicator Cluster Survey: 2006. Geneva, Switzerland

10 The wheat production of 2013 showed a decline of 40% compared to the trend of the previous 10 years and the livestock sector in Syria has significantly reduced. Source: See footnote 2.

11 See footnote 2.

12 Hoetjes M (2014) The impact of armed conflict on health in Al-Raqqah governate , Syria

13 Matasci-Phelippeau L (2013). Nutrition status of IDP population in Tal Abyad district