Evolution of WFP’s food assistance programme for Syrian refugees in Jordan

By Edgar Luce

By Edgar Luce

For the past two years, Edgar Luce has been working for WFP Jordan as a Programme Officer by monitoring operations, writing reports and acting as the VAM (Vulnerability Assessment and Mapping) focal point. He has more than five years of international experience in agricultural development and humanitarian relief working with NGOs prior to the UN.

Thanks to Henry Sebuliba, WFP for helping coordinate inputs, reviews and approvals in the article’s development.

For over three years, hundreds of thousands of Syrians have crossed the border into Jordan, seeking refuge from escalating violence. Increasingly, Syrians arrive with little more than the clothes on their backs, having suffered months of food insecurity due to the high cost of living and lack of employment opportunities in war-torn Syria. As fighting intensifies in the border regions of Dar’a, refugees are forced to walk longer distances through the desert to find safe passage into Jordan. Refugees in Jordan live among host communities across all of the country’s 12 governorates, as well as in Za’atari refugee camp, the Emirati-Jordanian camp, two smaller transit centres - King Abdullah Park and Cyber City in Irbid – and Azraq camp, which opened at the end of April 2014. With the number of Syrian refugees in Jordanian communities steadily increasing, public services ever more stretched and competition for employment intensifying, tensions between refugees and local communities are rising. Rental prices have more than doubled in northern Jordan, and the heavy burden on municipal utilities has led to blackouts and water shortages in multiple governorates across the country.

WFP assistance

WFP assistance

Since the onset of the Syrian refugee crisis in mid-2012, WFP has been providing food assistance to Syrian refugees in Jordan in a number of ways. WFP began providing food assistance through the provision of hot meals in Za’atari refugee camp when it first opened in July 2012. WFP transitioned to take home rations of dry ingredients by October 2012; this was followed by the provision of paper food vouchers that refugees can redeem in shops from September 2013 including the large supermarkets which opened in January 2014. In non-camp settings, assistance began with hot meals to a few hundred families in transit centres, followed by the introduction of paper vouchers in August 2012. In January 2014, the transition to e-vouchers began in communities and all UNHCR registered Syrian refugees should have an e-card by the end of August 2014. WFP’s voucher programme in Jordan is implemented through three established cooperating partners (Islamic Relief Worldwide, Human Relief Foundation and Save the Children International), and a fourth recent addition, ACTED, in the newly opened Azraq camp. This article describes the different types of assistance, how and why they evolved.

Food distributions in Za’atari refugee camp

Following the opening of Za’atari refugee camp in July 2012, WFP distributed hot meals from local restaurants to camp residents twice a day, typically consisting of rice, a protein source such as chicken or meat, together with bread, fruit and a vegetable. This was not sustainable for the rapid influx of refugees that followed (rising from 3,685 individuals in August 2012 to 129,756 in April 2013). Thus, WFP transitioned to the distribution of dry rations in October 2012, once kitchens with cooking facilities were available for camp refugees to use. The rations, consisting of rice, lentils, bulgur wheat, pasta, oil, sugar and salt, were distributed from dedicated distribution sites to all residents every two weeks. Together with the daily distribution of bread, this provided 2,100 kcal per person per day. UNHCR also provided additional complementary food normally consisting of canned tomatoes, tomato paste, tuna, canned beans and tea through the same distributions.

Paper voucher assistance

The paper voucher modality was introduced for the registered refugees living amongst the host community (August 2012 – 19,000 beneficiaries) and later in Za’atari camp (September 2013 – 104,000 beneficiaries). The introduction of the voucher programme helped bring a sense of normalcy to Syrian refugees allowing them to shop in regular supermarkets for their preferred foods. The vouchers also offered access to a greater diversity of foods with higher nutritional value, including fresh fruits, dairy products, meat, chicken, fish and vegetables. This programme also led to jobs for nearly 400 Jordanians in WFP’s partner shops where refugees used their vouchers; more than $229 million has been injected into the local economy since its launch through till July 20141.

In Za’atari camp, vouchers were initially redeemed in shops run by 16 partner community-based organisations (CBOs). In January 2014, WFP established two supermarkets in Za’atari camp allowing camp based refugees’ food needs to be met entirely through vouchers. WFP gradually decreased the distributions of dry food rations while increasing the value of the vouchers. Now that food assistance in camps has shifted completely to vouchers aside from the daily distribution of bread (due to concerns over the government bread subsidy), each refugee receives WFP monthly vouchers valued at 20JD (US$28.20). In communities refugees receive the full voucher value of 24JD (US$33.84) per person per month. This amount is based on the cost of a basic food basket which provides approximately 2,100 kcals per person daily. Ongoing monthly price monitoring conducted by WFP and its partners has shown that food prices in participating shops are similar, and often cheaper, than those in the non-participating stores2. Since January 2013, WFP has kept the voucher value constant at JOD24 (US$33.84) per person per month as food prices have remained relatively constant, even decreasing in some areas of Jordan3.

In April 2014, for the first time in the history of humanitarian assistance, Azraq refugee camp opened with a fully-fledged WFP supermarket along with WFP food vouchers. This meant that all refugees arriving in the camp could start purchasing their own food immediately.

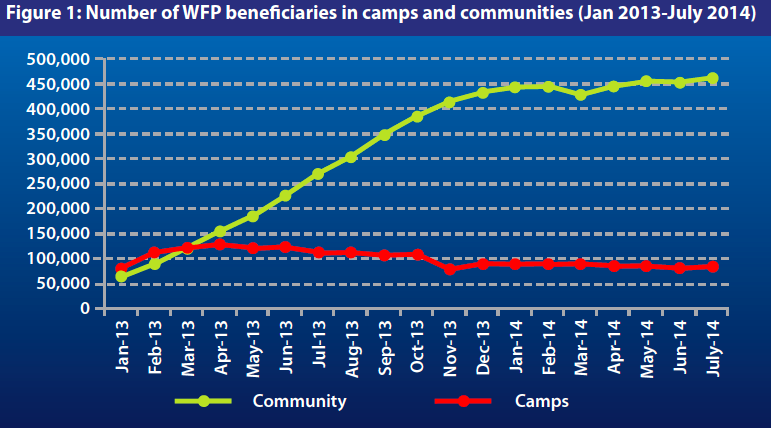

The number of beneficiaries of WFP’s voucher programme increased steadily from 67,500 individuals in January 2013 to 537,000 individuals by February 2014. All registered Syrian refugees living in host communities have been able to redeem their vouchers in 77 designated shops in 12 governorates (July 2014). Shops are contracted by WFP’s partners and are located in areas with a significant concentration of refugees. In these communities, the head of the household receives two paper vouchers every month. Each voucher is valid for two weeks and will expire if not used during the validity period. The voucher value varies according to the household size, as each individual receives the equivalent of 24JD (US$33.84) monthly.

E-voucher programme

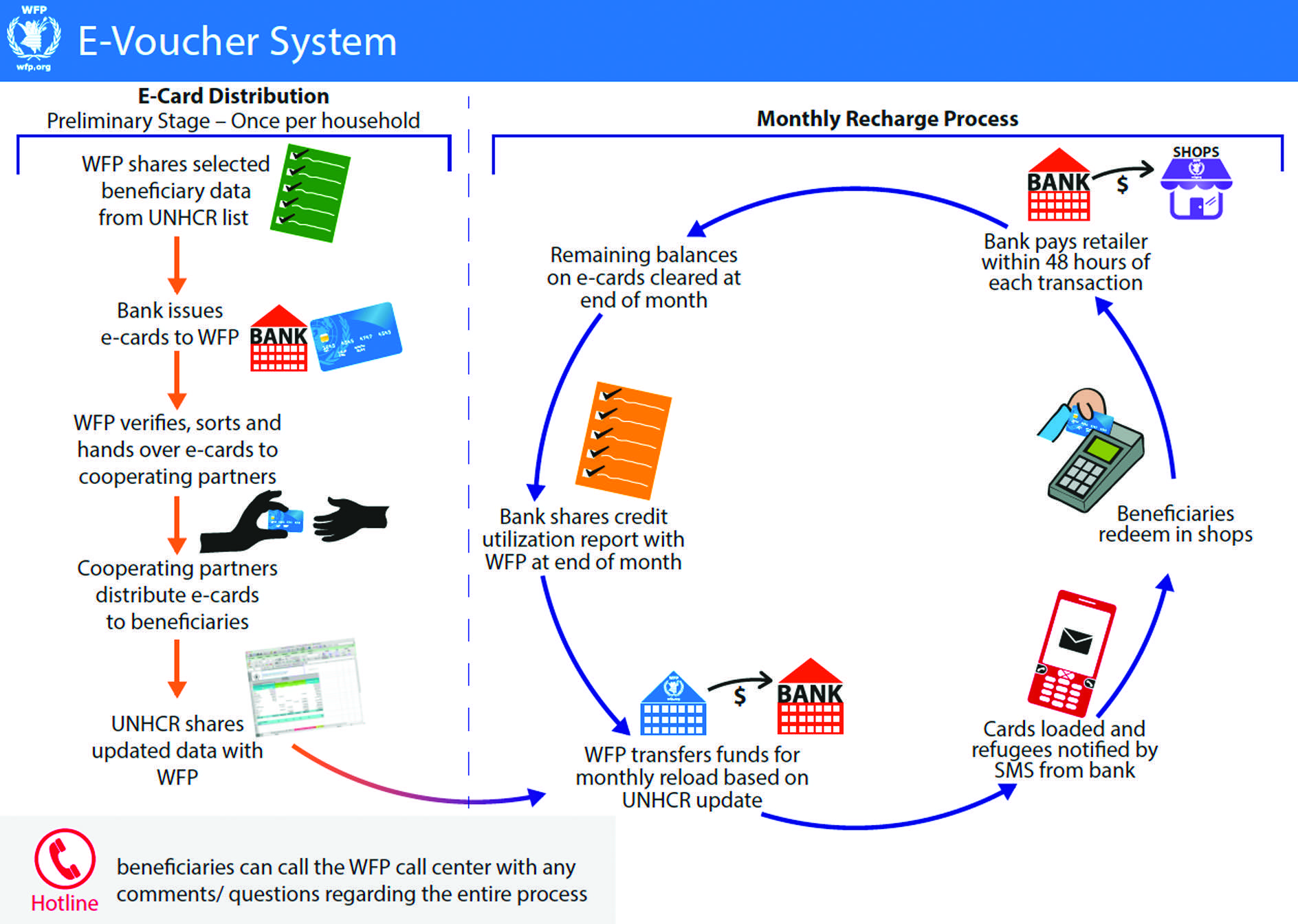

WFP assistance to Syrian refugees living amongst the host population in Jordan is now carried out through electronic food vouchers. This programme is implemented through a partnership with MasterCard and a local bank, Jordan Ahli Bank (JAB), under its Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) programme. E-vouchers function like a pre-paid debit card, with WFP transferring the voucher value directly to the e-voucher on a monthly basis through the partner bank (see Figure 1). WFP has now transferred almost all refugee households to electronic vouchers in the host communities and started to pilot this approach in camps as well. E-vouchers allow the beneficiaries to spend their entitlements in multiple visits to the shops and are also more discreet and therefore less stigmatising. As the cards are recharged automatically through the partner bank, beneficiaries are no longer required to travel to monthly distributions to receive their food assistance. When making a purchase in the supermarket, refugees must present their e-vouchers together with their matching UNHCR refugee identification card and input their four digit security code – the same process used for regular credit and debit cards.

Figure 1: WFP e-voucher system

Key findings and lessons learned

The paper voucher system was introduced as assessments showed that Jordan has a fully integrated market structure with the necessary commercial and physical infrastructure to meet increased consumer demand without affecting its current supply lines and price levels. Furthermore, since Syrian families are accustomed to shopping for their food, vouchers allowed them to continue their regular approach to purchasing food, helping to return a sense of normality to their lives while enabling them to select their preferred food items and meet their individual consumption and dietary needs. WFP keeps an open policy regarding what food items are selected; beneficiaries are able to purchase all food items except soda, chips and candy.

The WFP food voucher programme builds linkages between refugees and host communities and helps to stimulate local economies through the promotion of local production and sales. Findings from a recent WFP Economic Impact Study4 show that WFP assistance will equate to 0.7% of the Jordanian GDP through the voucher programme in 2014. The voucher programme has already led to some US$2.5 million investment in physical infrastructure by the participating retailers, created nearly 400 jobs in the food retail sector and generated almost US$6 million in additional tax receipts for the Jordanian government.

The gradual shift to e-cards brings several important benefits to both Syrian refugees and WFP. These include allowing refugees to spend their monthly entitlements in multiple visits to the shops (paper vouchers have to be spent in one go and only allow two shopping visits per month). This is useful for refugees who have limited storage facilities especially during the hot summer months or limited access to transportation. It also is a much more discreet assistance modality, which is important when living in host communities where tensions are increasing over time. While vouchers in general are more costly than the purchase of bulk commodities, given the transfer value of vouchers has to cover retail prices and is therefore higher per person than the cost of bulk food purchases, much less is also spent on administrative and logistical costs. Thus, with vouchers more total value is transferred to beneficiaries. Similarly, it is impossible to cost the added value for refugees in making their own household food decisions. With vouchers WFP was able to scale up quickly and absorb the high number of refugees crossing on a daily basis. Thus, vouchers are by far the preferred mode of assistance when compared with in-kind food in Jordan. E-vouchers are even more efficient given WFP does not need to print hundreds of thousands of paper vouchers every month, sort and distribute them through partners, then reconcile all redeemed vouchers. As part of the partner bank’s CSR programme, most services are provided to WFP free of charge, including the printing of all cards, loading of the monthly assistance and tracking and reporting.

WFP has a robust monitoring system that covers all activities such as e-cards, paper vouchers, school feeding in camps, nutrition activities. WFP monitors all partner shops, shop owners, prices in both partner and non-partner shops for comparison purposes, beneficiary perceptions, distribution sites and household food security information, such as food consumption scores and coping strategies on a regular basis. Because WFP assists nearly all registered Syrian refugees in Jordan, the prevalence of food insecurity amongst Syrian refugees is relatively low at 6% in communities5. Furthermore, food consumption is also high, as 90% have an acceptable food consumption score with only 8% classified borderline and 2% poor.

.jpeg?w=225) Initial monitoring findings of the e-card modality showed many Syrian refugees in Jordan are illiterate and thus unable to read and fully understand the voucher programme. In response, WFP created communication materials with illustrated explanations of the e-card process. Monitoring has also shown that shop owners are more satisfied with the e-card modality given they are paid much faster and do not need to track thousands of paper vouchers. Lastly, beneficiaries have explained their content with the voucher programme in general as they are more able to cover family members with specific dietary needs compared to the receipt of in-kind food.

Initial monitoring findings of the e-card modality showed many Syrian refugees in Jordan are illiterate and thus unable to read and fully understand the voucher programme. In response, WFP created communication materials with illustrated explanations of the e-card process. Monitoring has also shown that shop owners are more satisfied with the e-card modality given they are paid much faster and do not need to track thousands of paper vouchers. Lastly, beneficiaries have explained their content with the voucher programme in general as they are more able to cover family members with specific dietary needs compared to the receipt of in-kind food.

JAB, WFP’s partner bank, is responsible for setting up, maintaining and managing a safe, effective and efficient mechanism for the electronic voucher system though prepaid cards. The bank has established procedures for the control, oversight, monitoring and accounting of the prepaid card system and is responsible for providing, installing and maintaining point-of-sale machines in all selected retailers. The bank is also responsible, if necessary, for establishing bank accounts for all WFP retailers and for producing prepaid cards for each bene?ciary household. It is also the role of the partner bank to provide comprehensive and timely reporting on beneficiaries’ card use and subaccount activity. The bank has designated an experienced customer support focal team for project implementation, monitoring, facilitation and coordination, while providing WFP and cooperating partners with remote web access for card maintenance and account/transactions information. Lastly, the bank is providing facilities such as help desks, call centres and help lines as well as system training to WFP, cooperating partners and retailers in addition to ?nancial literacy training for beneficiaries.

In addition to the WFP hotline hosted by the bank, all partners have hotlines as an effective beneficiary feedback mechanism - answering questions on locations of distributions and shops, referring beneficiaries to other agency hotlines for non-food related issues, relaying lost e-card or forgotten pin numbers to the bank and counselling beneficiaries on how to use the e-card. On average, WFP receives more than 1,500 calls per month through its hotlines. All partners are also required to operate hotlines as well.

Sustainable funding, including ensuring the timing of donations to meet cash flow requirements, continues to pose challenges for future food assistance. Maintaining the cash flow and ensuring contingency stocks are ready to assist a possible large influx of refugees is extremely challenging when working with a funding horizon of one month. Given the fiscal costs of current refugee operations around Syria, WFP is working with sister agencies and host governments to devise a more mid-term approach to affording Syrian refugees the ability to provide for themselves even in a time of crisis.

For more information, contact: Dina Elkassaby, Press Information Officer – WFP Syria Regional Emergency, email: Dina.elkassaby@wfp.org

1 Economic impact study: Direct and indirect impact of the WFP food voucher programme in Jordan, April 2014.

2 For example, in April 2014, a standard food basket cost JOD21.60 (US$30.24) in participating stores and JOD21.80 (US$30.52) in the non-participating outlets. Source: Economic impact study: Direct and indirect impact of the WFP food voucher programme in Jordan, April 2014.

3 Food basket is composed of rice, bulgur wheat, pasta, pulses, sugar, vegetable oil, salt and canned meat.

4 Economic impact study: Direct and indirect impact of the WFP food voucher programme in Jordan, April 2014.

5 Findings from the Comprehensive Food Security Monitoring Exercise (CFSME) conducted in January 2014, report released July 2014. http://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/ep/wfp266893.pdf