GOAL’s food and voucher assistance programme in Northern Syria

By Hannah Reed

By Hannah Reed

Hannah Reed is the former Assistant Country Director for Programmes in GOAL’s Syria Programme. She has over 10 years of experience in the humanitarian and development sector, working in Bolivia and the Fairtrade Foundation, before joining GOAL in 2011. Since joining GOAL, Hannah has worked in the field and support offices in GOAL’s Sudan, Haiti and Syria programmes.

With thanks to Hatty Barthorp, GOAL’s Global Nutrition Advisor, and Alison Gardner, Nutrition Consultant, for their technical support.

Context

GOAL's response to the Syria crisis began in November 2012. To date, it has provided vital food and non-food aid to over 300,000 beneficiaries through both direct distributions and voucher programming in Idlib and Hama Governorates, Northern Syria, in addition to increasing access to water for over 200,000 people in northern Idlib.

GOAL Syria currently receives funds from four donors (OFDA, FFP, UKAID and ECHO1). Under OFDA, GOAL implements voucher-based and in-kind Non-Food Items (NFIs) and winterisation support. FFP funding provides Family Food Rations (FFR) and support to bakeries with wheat flour alongside a voucher-based system for the most vulnerable households to access bread. A UKAID grant focuses on improved access to safe water, hygiene and sanitation and improved food security through a mixed-resource transfer model combining dry food distributions with Fresh Food Vouchers (FFV). Finally, Irish Aid and ECHO support unrestricted vouchers and cash for work to increase access to food and NFIs in areas with safe access to functional markets.

At the time of writing (May 2014), GOAL’s food assistance programme is reaching upwards of 240,000 direct beneficiaries each month. Monthly unrestricted (food and NFI) vouchers are targeting 5,790 people, expanding to a total 13,200 direct beneficiaries each month from June 2014, while voucher-based assistance to meet winterisation needs reached over 72,000 people during winter 2013/14. Funding has also been secured to expand voucher-based assistance to increase access to inputs required for the protection and recovery of livelihoods and to include food production.

GOAL’s Food Security programme implementation and design has been informed by various assessments and studies completed over the past six months. These include a Food Basket Assessment (August 2013), Emergency Market Mapping and Analysis (EMMA) studies on markets for wheat flour and vegetables (January 2014) and dry yeast, rice and lentil (May 2014), a Food Security Baseline (December 2013) and Multi-sector Needs Assessment (January 2014). Design and implementation also continue to be informed by ongoing Post Distribution Monitoring (PDM) of all programme activities.

Programming context, including challenges due to access and security

The protracted conflict has resulted in urgent, humanitarian needs across Syria. The United Nations (UN) estimates that the conflict has displaced at least 6.5 million people within Syria, with a further 2.5 million refugees in neighbouring countries2. A combination of direct and indirect factors has led to in excess of 9.3 million people classified as in need of humanitarian assistance. With reference to aid required per sector, the Syria Integrated Needs Assessment (SINA) found the highest number of people in need across the sub-districts surveyed were in need of food assistance, with an estimated 5.5 million people food insecure in assessed areas of northern Syria, including 4.9 million in moderate need and 590,600 in acute or severe need3.

Resulting in displacement, reduced access to livelihoods and market disruption, in addition to the direct loss of life and damage to infrastructure, the protracted conflict continues to negatively impact negatively on the ability of affected populations to meet basic food and other needs without assistance. Increased reliance on coping strategies reduces household resiliency and results in increased immediate and sustained humanitarian need.

In tandem, the operational and security context continues to present challenges to the impartial and safe delivery of humanitarian aid. An increasingly fractured opposition force and changes in power dynamics requires continual operational adjustments to ensure aid can pass freely through check-points held by different and continually changing factions. Highly fluid changes within the opposition movement areis accompanied by an increasing trend of Government military action in opposition-held areas of northern Syria, resulting in continued population displacement and a highly insecure operational environment for aid agencies. Deterioration in security in areas of Syria close to the border with Turkey, have also resulted in periodic and often prolonged border closures (notably in January 2014) which in turn prevent and/or delay cross-border delivery of aid to conflict-affected populations in Syria.

Assessments which informed the food kit design

The designs of GOAL’s Family Food Ration (FFR) and complementary fresh food vouchers4 for distribution from Autumn 2013 up to early Summer 2014, were informed by GOAL’s Food Basket Assessment5 (and supporting assessment of fresh food availability on local markets) completed in August 2013. The survey objectives were to obtain information on diet quantity, diet diversity, feed frequency, food availability, nutritional deficiencies and access, to produce an evidence base and recommendations for the contents of GOAL’s FFR, and to reassess the profile of GOAL beneficiaries, including household size and composition of the household.

Key survey findings were:

-

Percentage of households with at least one household (HH) member that havewith specialised nutritional requirements: children aged 5 years and younger (66%6), elderly (15%), Pregnant and Lactating Women (PLW) (30%), and members with chronic illness or disability (27%).

-

Average monthly income per HH is SYP 7,279 ($29) while average monthly expenditure on food per HH was reported as SYP 9,265 ($37).

-

Ratio of HH member contributing to income to dependent HH members = 1:4

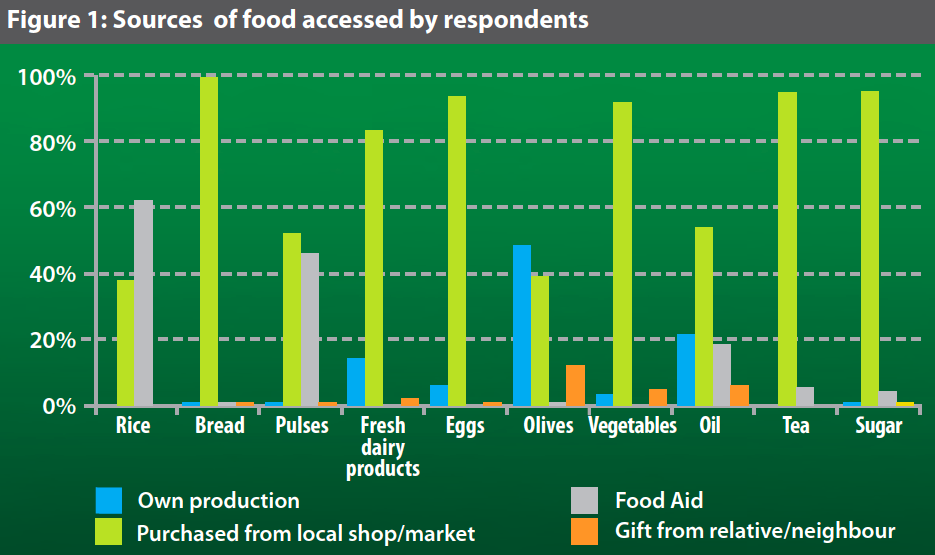

Figure 1 shows that the primary source of all food groups was purchase from local markets. The average monthly food expenditure reported exceeds average monthly income, suggesting a high risk of food insecurity in the absence of assistance to access food, and a need to rebuild livelihoods to increase income levels.

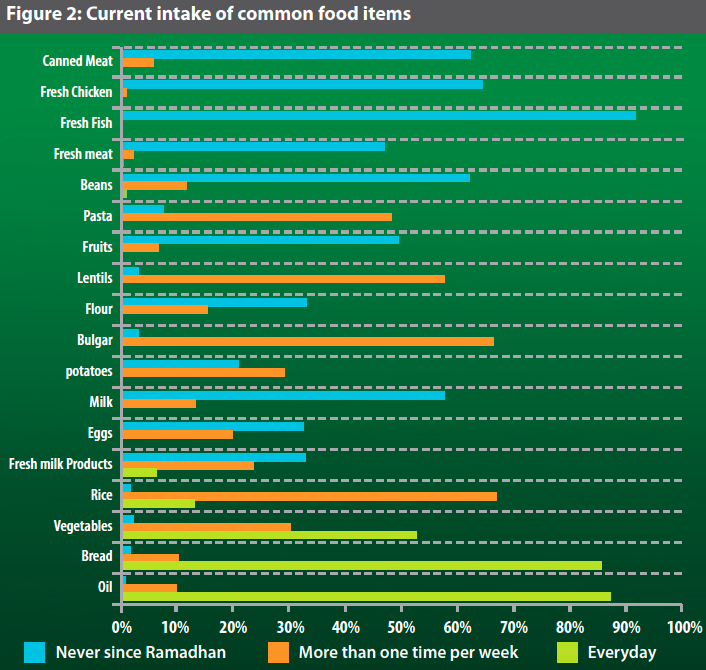

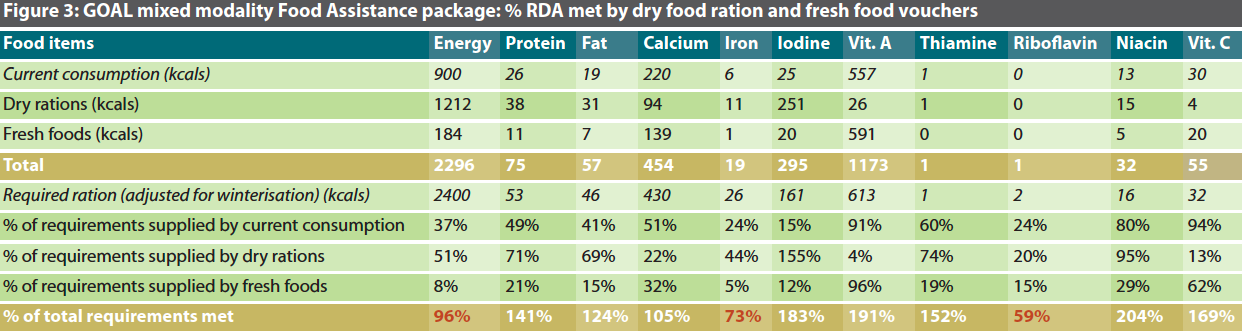

To assess current dietary diversity, respondents were also asked how often they consumed food items from a specified list of foods common in Syria (see Figure 2). Ramadan was 3 weeks before the household survey7. The results (Figure 2) reveal very low levels of dietary diversity with the population heavily reliant on bread and vegetables. The main additional foods consumed (eaten more than once a week) were other cereals, such as rice, bulgur and pasta, as well as lentils. Results of the assessment in terms of the % Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) for kilocalories and micro- and macro-nutrients showed that households were able to meet an average of 900 kilocalories per person per day without assistance. The % RDA met without assistance was high for vitamin A (91%) and Vitamin C (92%) and low for protein (49%), fat (41%), iron (24%) and iodine (15%).

Design of different food kits and resulting operational difficulties

In response to these findings, GOAL designed two types of food ration. The FFR included tahini, raisins, fava beans and chick peas for distribution in areas without functioning markets, and therefore not receiving vouchers to access fresh food. In areas with safe access to functioning markets, a dual-transfer food assistance package was distributed that included both a dry food ration and vouchers to access food (see Figure 3 for nutrient composition including % RDA).

All food assistance was designed to meet a target of 2,400 kcals p/d adjusted from the Sphere standard (2,100 kcal p/p/d) by an additional 300 kcals p/d in order to meet increased calorific requirements during the winter period. For areas targeted by direct distribution of dry food rations only, GOAL designed two types of food kit - a full FFR and a reduced FFR. The latter was provided where targeted beneficiaries were also receiving a daily bread ration (457 kcal per person per day (pppd) via bread vouchers) under complementary GOAL programming; in this instance, the FFR contained reduced quantities of pasta, rice and bulgur wheat. For both FFR types, full and half kits were also provided, designed to ensure the RDA pppd was met and allocated according to household size.

In practice, disruption to border crossings resulted in frequent delivery of only one type of food ration. This disrupted distribution as it was necessary to wait for delivery of contingents of all food ration specifications to cross the border. Otherwise, distributing food kits to all registered households in any given village at different times had the potential to create security issues.

Modified food assistance modality

Given the unreliability of border crossings, the design of food kits has been greatly simplified for the next round of food security programming with one type of half kit only. Households will receive between one and three half kits each month depending on household size. A repeat of the Food Basket Assessment is planned for early June 2014 to inform the final specifications of the FFR. This will focus specifically on the % RDA currently met by targeted groups without assistance, and will ensure the RDA per person per day is met in terms of calorific and nutrient requirements. It is expected that the % meeting the RDA without assistance will have declined since August 2013, due to:

-

Continued trend of price increases in food items

-

Reduced purchasing power as conflict affected households deplete remaining savings, and

-

Disruption to livelihood activities pre-conflict and the corresponding decrease in income generation capacity for much of the population.

GOAL’s assessments in 2014 demonstrate a trend of decreasing food security within populations without access to regular food assistance. Table 1 shows average Household Food Consumption Scores (FCS) for populations surveyed in GOAL’s operational areas during October 2013, December 2013 and January 2014.

Table 1: Trends in Household Food Consumption Score (FCS) |

|||||||||

|

Average |

Male headed households |

Female headed households |

|||||||

|

Oct-13 |

Dec-13 |

Jan-14 |

Oct-13 |

Dec-13 |

Jan-14 |

Oct-13 |

Dec-13 |

Jan-14 |

|

|

% households scored ‘acceptable’ |

43% |

22% |

15% |

40% |

23% |

15% |

58% |

43% |

18% |

|

% households scored ‘borderline’ |

50% |

47% |

42% |

56% |

48% |

45% |

40% |

43% |

0% |

|

% households scored ‘poor’ |

7% |

31% |

43% |

4% |

28% |

40% |

2% |

14% |

82% |

Table 1 demonstrates progressive deterioration in household food security across targeted areas, with a striking increase in the number of female headed households ranked with a ‘poor’ FCS (82%) in January 2014 when compared to male headed households surveyed at the same time and in the same areas (40%). A sharp decline can also be seen in January 2014 figures when compared to the % of female headed households ranked with poor FCS in October (2%) and December 2013 (14%).

Food security is undermined by the type of income source, with the majority of households surveyed currently relying on irregular jobs (44%), the sale of personal assets (29%), assistance received from relatives (17%) and previous savings (7%)8. This represents a worrying trend as there are only a finite number of assets that may be sold or savings that may be utilised. On average, irregular jobs only generated USD $65 / 9,724 Syrian Pounds (SYP) in the month prior to the survey, compared to the sale of personal assets (the highest source of income reported) which generated an average of USD $415.5 / SYP 62,018 over the same period.

Correspondingly, the average monthly expenditure on food alone across the sample was USD $81 / SYP 12,105 significantly higher than the average income generated by irregular jobs, which represents the most common source of income referenced. Households also reported that most of their income was not generated by jobs or livelihoods but by the use of coping strategies; 22% of the income source was through the sale of personal assets, whereas a further 22% was credit – strategies which are not sustainable9. Sixty eight per cent of households surveyed also reported outstanding debt, with 72% of these reporting that credit obtained had been used to purchase food. Other coping strategies identified to meet food needs include relying on less preferred or less expensive food (62%), taking on credit (29%), limiting portion sizes (25%), borrowing food (19%), and taking children from education to work (17%) or sending children or other family members to live with relatives (15%)10.

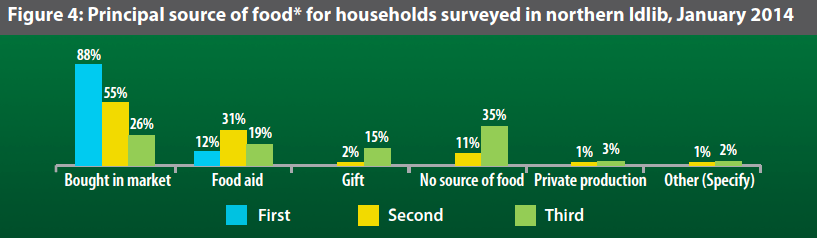

Recent surveys, reinforced by Emergency Market Mapping & Analysis (EMMA) studies on critical markets for tomatoes, potatoes, rice and lentils, reinforced the trend that food remains available in areas with functioning markets (see Figure 4). However, food remains inaccessible to many households in these areas due to reduced livelihood options and the widening gap between household expenditure and income.

*Respondents could give up to three sources of food ranked in order of importance as principalle source of food.

Change of GOAL direction to include voucher programming

Given that access as opposed to availability represents the critical barrier to households meeting basic food needs without assistance, GOAL will expand the current FFV modality to include vouchers for both dry and fresh food in the next phase of food security programming. This recognises increased flexibility afforded by a market-based approach in areas with functional markets and when compared to direct distributions alone, reducing reliance on border crossings and the transportation of food rations when relying only on direct distributions. This approach also recognises beneficiary preference for vouchers. A dual resource transfer approach also provides maximum operational flexibility, with the option to increase or decrease the ration of assistance provided via vouchers and via direct distributions in response to changes in market systems or in the security context.

This approach has been informed by GOAL’s understanding of market systems developed through EMMAs on critical markets for dry and fresh food, and by experience to date with fresh food vouchers and in addition to ongoing unrestricted and NFI voucher programming. Food assistance will be delivered through monthly food voucher distributions in areas which will sustain a market-based approach, and through dry food rations in areas without safe access to functioning markets.

The use of vouchers – when market systems permit – also seeks to ‘do no harm’ both to local markets and to livelihoods, by avoiding the potentially negative impact of large volumes of imported food goods being distributed in areas where markets continue to function11.

GOAL welcomes the formation of a Cash Based Response Technical Working Group (Cash TWG) for actors implementing the cross-border response in northern Syria. GOAL is participating actively on the working group and has recently presented GOAL’s voucher process (outlined below) in response to requests from other members. The Cash TWG has been formed to support lesson learning and exchange of best practice with reference to cash and voucher based programming in northern Syria and to improve coordination. With a market-based approach to assistance, it is critical that actors coordinate to ensure a ‘Do No Harm’ approach is applied to local markets. This will mitigate against the risk of ‘flooding’ / crashing local markets should there be a significant and uncoordinated increase in voucher-based programming by other actors, reliant on the same markets, within the same timeframes.

Details of the voucher programme design

Food vouchers will build on GOAL’s established voucher modality, taking the form of printed, cash-based vouchers distributed on a monthly basis and exchangeable for food items only at selected and registered traders.

Following an assessment by GOAL field staff of trader’s stock and capacity to restock and to gauge willingness to engage with the conditions of GOAL’s voucher scheme, traders sign a contract with GOAL to participate in the voucher scheme. This includes a commitment on the part of the trader only to only redeem agreed items for GOAL vouchers exchanged by beneficiaries, namely dry and fresh foods for food security interventions (see Box 1 for decision making regarding vouchers related to infant feeding)12. Punitive measures are in place and communicated to traders regarding infractions to the stated terms of the contract. This includes temporary moving to permanent exclusion from the voucher scheme if substantial evidence exists that vouchers have been exchanged for items outside the scope agreed by GOAL with traders and stipulated on the vouchers, in additions to other breaches of the contract signed.

Food vouchers are eligible for one month and redeemed for food by beneficiaries in a range of registered shops. Lists of shops participating and the prices charged for key food goods are distributed to beneficiaries with vouchers. Participating shops are also required to display the agreed price list in their outlets to reduce the risk of voucher beneficiaries being punitively charged for goods purchased with vouchers. Prices for food goods exchanged with vouchers are set in line with average market prices for these goods, and are not intended to be ‘cheaper’ than the same goods purchased in the same markets by non-beneficiaries and using cash. GOAL vouchers continue to incorporate a series of security features13, while a rigorous system of checks ensure only the selected families receive and redeem the vouchers; that the vouchers are used for NFIs only; that the traders cannot increase prices arbitrarily and that any complaints are quickly relayed to GOAL for investigation14.

Shopkeepers redeem vouchers with GOAL staff on a weekly basis and are reimbursed for the value of food items exchanged for vouchers. There are currently over 200 outlets registered with GOAL’s voucher scheme offering a wider range of food and NFIs. GOAL is currently providing fresh food assistance to upwards of 10,000 households each month via a voucher-based modality. Initial assessments and demand from traders not currently registered demonstrating demonstrate that scope exists to further expand further the food voucher scheme under the proposed modification.

Box 1: Decision making around exclusion of infant formula and milk powder from the voucher scheme and food distribution

Both breastfeeding and use of breastmilk substitutes (BMS) – typically infant formula – is common in the population. In the January 2014 Needs Assessment, in nine sub-districts (Armanaz, Badama, Darkosh, Harim, Janudiyeh, Kafr Takharim, Maaret Tamsrin, Qourqeen, and Salqin) of Idlib Governorate, 25% of respondents reported infants 0-5m were being fed milk (regular, tinned, powdered or fresh animal milk), a further 17% of infants 0-5m were being fed infant formula and 41% reported other foods/liquids. Three-quarters (75%) of respondents also reported breastfeeding their infant. Various difficulties with breastfeeding were reported, such as too stressed to breastfeed (13%) and inadequate maternal food intake (29%).

Access to breastfeeding support and to BMS supplies for mothers is very limited in our target population. An international non-governmental organisation (INGO) is running an IYCF programme in just five of the 134 villages that GOAL currently operates in, though this may be expanding which may bring more opportunities to collaborate. Infant formula is expensive; the price of infant formula has risen significantly through the crisis. Untargeted distribution of infant formula (ready-to-use and powdered products) is happening in the northern governorates (source: GNC scoping mission, Sept 2013); one INGO is collaborating with a number of these to minimise risks.

On balance, it was decided that GOALs vouchers and dry rations should not include a BMS as we do not have the capacity or relevant partnerships established to ensure appropriate targeting and also provide the requisite level of support/guidance to mothers. The hygiene-sanitation conditions are poor and access to safe water is a problem. Households still have a certain level of income from various sources, whereby GOAL FSL project is trying to protect assets and the income generation pot’, by providing access to as replete a diet as possible. We excluded BMS to reduce the risk of families choosing BMS or other powdered milks over breastfeeding. Those who are dependent on BMS still have the potential to buy from local markets, as a greater proportion of their personal income would be available to spend on ‘essential items’, given the food/vouchers provided by GOAL. In January 2014, the predominant expenditure for all households remained food, followed by health, water then fuel.

Lessons learnt on voucher programming so far and vision for future.

To date, GOAL’s experience with voucher-based programming demonstrates that this is an appropriate and effective modality to increase access to basic needs for populations in northern Syria with safe access to functional markets. PDM demonstrates that targeted distribution of vouchers affords greater flexibility to beneficiaries than direct distributions (which is of particular relevance to address the needs of women and children) whilst simultaneously strengthening local markets, as evidenced by positive feedback from market actors. A recent survey of shopkeepers participating in GOAL’s voucher scheme found that 100% reported that they would like to sign future agreements with GOAL. In addition, a recent rapid assessment found that 88% of key informants surveyed who were aware of GOAL’s voucher system believe it has a positive impact on the market, while 71% of shopkeepers interviewed who were familiar with the system stating stated that they would be very interested in participating. An average of 93% of beneficiaries stated that the frequency of vouchers was appropriate to their needs, while 81.5% of beneficiaries responded that they were satisfied with the range of shops available to them15.

To date, GOAL’s experience with voucher-based programming demonstrates that this is an appropriate and effective modality to increase access to basic needs for populations in northern Syria with safe access to functional markets. PDM demonstrates that targeted distribution of vouchers affords greater flexibility to beneficiaries than direct distributions (which is of particular relevance to address the needs of women and children) whilst simultaneously strengthening local markets, as evidenced by positive feedback from market actors. A recent survey of shopkeepers participating in GOAL’s voucher scheme found that 100% reported that they would like to sign future agreements with GOAL. In addition, a recent rapid assessment found that 88% of key informants surveyed who were aware of GOAL’s voucher system believe it has a positive impact on the market, while 71% of shopkeepers interviewed who were familiar with the system stating stated that they would be very interested in participating. An average of 93% of beneficiaries stated that the frequency of vouchers was appropriate to their needs, while 81.5% of beneficiaries responded that they were satisfied with the range of shops available to them15.

GOAL will therefore continue to increase access to food and other basic needs through a voucher-based modality, as the preferred option in areas with safe access to functional markets. This will be supported by continued direct distributions of food assistance when security or market capacity does not permit a market-based approach. Through continued emphasis on robust monitoring of the impact of assistance on food security, and on market impact of modalities employed, GOAL will scale up the use of vouchers in preference to direct distributions.

For more information, contact: Vicki Aken, Country Director, GOAL Syria, email: vaken@goal.ie

1US Office for Disaster Assistance; US Food for Peace; UK Aid Department for International Development (UK), European Commission Humanitarian Office

2UNOCHA Syrian Humanitarian Bulletin Issue 44, 27 February – 12 March 2014

3Syria Integrated Needs Assessment, December 2013

4Fresh Food vouchers were distributed with dry food rations over this period, and only in areas where local markets will sustain a voucher-based approach

5A household survey was conducted in August 2013, using convenience sampling of 607 randomly selected households in GOAL’s operational areas. The sample covered 82% beneficiaries (of non-food aid) and 18% non-beneficiaries and a mix of rural and urban areas. Data was were then triangulated through in-depth interviews in the same districts. The ‘NutVal’ tool was used for analysis of nutrient composition, while secondary data from FSLWG and OCHA, WFP documents was were also referenced. In terms of limitations, some areas were inaccessible to the data collection team due to security constraints while challenges were also experienced with regards to respondents’ ability to recall daily food intake.

6Of which the average households sampled had 0.46 household members aged two years and younger, and 0.90 household members aged between three and five years.

7Possible answers were: never since Ramadan, more than once per week, and everyday

8Needs Assessment in northern Idlib, January 2014, GOAL.

9Ibid

10Ibid

11The EMMA on rice and lentil critical markets completed in May 2014 by GOAL suggested that large-scale influxes of these food types via aid agency distributions may be impacting local markets systems for these commodities

12Note that shopkeepers include a strict ban on the exchange of vouchers for alcohol, cigarettes, infant formula and powdered milk. GOAL programme and M&E staff will continue closely to monitor shopping periods to ensure contractual requirements are met, and including that NFIs are not exchanged for food vouchers. The ban on exchange of vouchers for infant formula and powdered milk is in line with GOAL’s policy of safeguarding children and the international Operational Guidelines for Infant Feeding in Emergencies (2007) which state that “infant formula should only be targeted to infants requiring it, as determined from assessment by a qualified health or nutrition worker trained in breastfeeding and infant feeding issues” See Box 1 for more considerations around infant formula/powdered milk exclusion from the voucher scheme.

13There are two serial numbers, one is random and one is computer generated and therefore unpredictable. Each voucher has a hologram which is GOAL-specific, patented and only produced in one factory in Turkey. There is a different colour for each batch of vouchers. Watermarks are incorporated into the design, which are very difficult to forge and there is also a complex pattern on the surface and exact measurements of the font. Replication of vouchers is therefore extremely difficult.

14This system includes: price setting with participating shopkeepers prior to each round of distributions with price lists then displayed in participating outlets; the use of ‘shopkeeper books’ to register beneficiary names, ID numbers and voucher numbers against the items these are exchanged against; careful selection of shopkeepers against established accessibility and stock level criteria followed by signatures of contracts agreeing to abide by the terms and conditions of GOAL’s voucher scheme; and clearly defined shopping and voucher redemption periods to guarantee close monitoring by both programmes staff and GOAL’s M&E team to ensure guidelines are adhered to and to reduce the risk of unauthorised duplication or use of GOAL vouchers.

15PDM Irish Aid Vouchers Rounds 1 and 2