International Legal Consequences of the Conflict in Syria

By Natasha Harrington

By Natasha Harrington

Natasha is a barrister (a member of the English Bar). She is currently working in Eversheds law firms’ public international law and international arbitration group in Paris. Natasha’s practice includes advising and representing governments, international organisations and private clients on a wide range of public international law matters. She has a particular interest in international humanitarian law and international human rights law. In this regard, she regularly undertakes pro bono work and has previously worked for Amnesty International. Natasha has also undertaken training in international humanitarian law with the International Committee of the Red Cross.

The ENN is a partner of the charity A4ID1 through which we secured the pro bono services of Natasha Harrington to develop an article about the legal framework around military intervention on humanitarian grounds. We extend sincere thanks to A4ID (particularly John Bibby, Head of Communications and Policy) for brokering this arrangement, to Eversheds law firm for supporting this endeavour, and to Natasha, who went way beyond her initial remit to accommodate our questions and an ever-complicating context.

Article completed 20 June 2014.

A. Introduction

A. Introduction

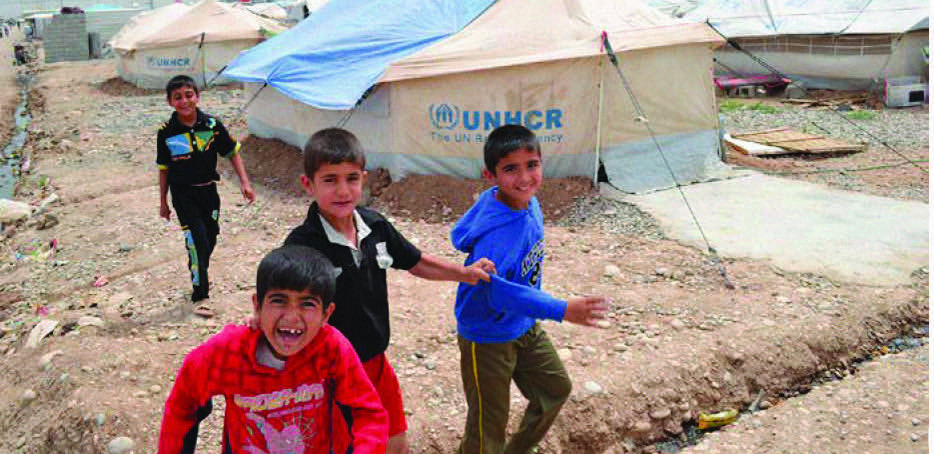

The term “humanitarian catastrophe” has particularly profound meaning in relation to the situation in Syria. After three years of civil war, over 150,000 people are estimated to have been killed and more than 2.5 million Syrians (over 10% of the population) have fled to neighbouring countries. In addition, at least 9.3 million Syrians inside Syria are in need of humanitarian assistance, over 6.5 million of whom are internally displaced2.

The existence of a “humanitarian catastrophe” is a trigger point for action under certain doctrines of international law. For example, the Responsibility to Protect (or R2P) doctrine recognises an obligation on the international community to prevent and react to humanitarian catastrophes. Certain international lawyers and States, including the UK, also argue that under international law it is permissible to take exceptional measures, including military intervention in a State, in order to avert a humanitarian catastrophe (hereafter referred to as “humanitarian military intervention”)3.

This article examines the legal consequences of the humanitarian crisis in Syria. It addresses:

a) the serious breaches of international humanitarian law and international human rights law committed by the parties to the conflict (Section B)

b) the responsibility of the international community to react to the crisis in Syria, and in particular, the “Responsibility to Protect” (Section C), and

c) the scope, under international law, for intervention in Syria by third States without UN Security Council authorization (Section D).

B. Breaches of International Law during the Conflict in Syria

Documenting all of the violations of international law carried out during the Syrian conflict would be an immense task, one that perhaps only the International Criminal Court (ICC) or a specialist tribunal could attempt (see below). Therefore, this section highlights just some of the most grievous violations of the rules of international law carried out by the parties to the conflict in Syria.

Applicable Legal Rules

The rules of international humanitarian law apply to the conflict in Syria because it is a non-international armed conflict: an intense conflict between a government and a number of well-organised rebel groups. In addition to international humanitarian law, international human rights law continues to apply in Syria4. For example, Syria is a party to the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights (the ICCPR) and the Convention Against Torture.

Violations of International Law by the Parties to the Conflict in Syria

1. Protection of civilians and distinction: the parties to the conflict must not attack civilians, and must always distinguish between civilians and combatants and civilian objects and military targets. The parties to the conflict must not undertake “indiscriminate attacks”, which by their nature strike civilians and military objectives without distinction.

This rule has been repeatedly violated by both sides to the conflict. In particular, the use by government forces of barrel bombs in civilian areas violates the rule of distinction. In May 2014, the UN Secretary-General reported that:

“Indiscriminate aerial strikes and shelling by Government forces resulted in deaths, injuries and large-scale displacement of civilians, while armed opposition groups also continued indiscriminate shelling and the use of car bombs in populated civilian areas5.”

2. Torture and inhuman treatment: the use of torture is absolutely prohibited, and cannot be justified by a state of emergency or war6.

An Independent International Commission of Inquiry for Syria (the Commission of Inquiry), set up by the UN Human Rights Council, has found evidence of the widespread use of torture, as well as incidents of starvation and sexual violence, in government detention facilities7. Recently, certain rebel groups such as the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham8 (ISIS) are reported to have increased their use of torture against civilians9.

3. Prohibition against the use of starvation of the civilian population as a method of warfare: the use of starvation against the civilian population is absolutely prohibited. This means that, for example, during a siege civilians must be able to leave, and food and humanitarian supplies must be allowed access to, the besieged area. The Commission of Inquiry has noted reports of starvation in areas besieged by the Syrian authorities, such as Yarmouk10. Human rights groups have accused the Syrian government of using starvation as a weapon of war11.

4. Prohibition against the use of chemical and biological weapons: the use of chemical and biological weapons in armed conflict is also strictly forbidden under international law. However, a chemical weapons attack on 21 August 2013 reportedly killed hundreds of people. A recent UN report on the situation in Syria also contained information about the use of toxic gas12.

5. Protection of humanitarian relief personnel and medical personnel and facilities: the parties to the conflict must protect and respect humanitarian relief and medical personnel. Medical facilities must be protected and must not be attacked.

6. In September 2013, a group of doctors published an open letter in The Lancet in which they cited “systematic assaults on medical professionals, facilities and patients … making it nearly impossible for civilians to receive essential medical services13”. Some health facilities have been repeatedly attacked, and over 460 healthcare workers have reportedly been killed in Syria14. UN staff and medical professionals have also been abducted or detained by the Syrian authorities and rebel groups15.

7. Access to Humanitarian Relief: rapid and unimpeded access to humanitarian relief for all civilians in need, without distinction, must be ensured by the parties to the conflict.

Both the Syrian government and rebel forces frequently interrupt access to humanitarian relief, particularly basic medical equipment16. For example, a report by the UN Secretary-General states that:

“Medical supplies including life-saving medicines and vaccines, and equipment for the wounded and the sick are commodities privileged through the Geneva Conventions. Denying these is arbitrary and unjustified, and a clear violation of international humanitarian law. Yet, medicines are routinely denied to those who need them, including tens of thousands of women, children and elderly. The Security Council must take action to deal with these flagrant violations of the basic principles of international law17.”

Security Council Resolution 2139, adopted on 22 February 2014, demanded unhindered humanitarian access in Syria “across conflict lines and across borders”. Its preamble states that the arbitrary denial of humanitarian access may constitute a violation of international humanitarian law. However, the Syrian government refuses to authorise cross-border deliveries of aid through border crossing points that it does not control18, including crossing points identified as “vital” to reach over one million people in areas that are otherwise impossible to reach19.

In an open letter to the UN Secretary-General, a group of legal experts argued that if consent for relief operations is arbitrarily withheld by the Syrian authorities, then such operations may be carried out lawfully without consent20. However, the UN has not accepted this advice. It has maintained that the consent of the Syrian government is necessary for humanitarian operations, unless the UN Security Council specifically authorises such operations under Chapter VII of the UN Charter21.

In a recent report, the UN Secretary-General called on the Syrian government to allow cross-border aid deliveries and said that by withholding its consent, the Syrian government “is failing in its responsibility to look after its own people22”, invoking the language of Responsibility to Protect. Recently, it has been reported that UN diplomats are discussing a Security Council resolution that would authorise cross-border aid and threaten sanctions if the Syrian government fails to comply23. In the meantime, however, aid organisations that engage in unauthorised cross-border activities risk expulsion or even attack by the Syrian government24.

Summary

The scale of the violations of international law committed in Syria is such that the Commission of Inquiry describes evidence “indicating a massive number of war crimes and crimes against humanity suffered by the victims of this conflict25”. War crimes are grave breaches of international humanitarian law, and crimes against humanity are acts such as murder, torture and sexual violence committed as part of a widespread and systematic attack against a civilian population.

These offences could be tried by the ICC. However, because Syria is not a member of the Court’s statute, the ICC has no jurisdiction unless the situation in Syria is referred to it by the UN Security Council. A draft Security Council resolution referring the situation in Syria to the ICC was vetoed by Russia and China on 22 May 201426.

Therefore, there is a risk that war crimes and crimes against humanity will continue to be committed with impunity in Syria. In light of the gravity of the situation, we turn to examine the responsibility of the international community to respond to the crisis in Syria.

C. Responsibility of the International Community to Respond to the Situation in Syria

C. Responsibility of the International Community to Respond to the Situation in Syria

The R2P doctrine was developed by an International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS) following the failure of the international community to prevent humanitarian catastrophes in Rwanda in 1994 and Srebrenica in 1995.

R2P operates at two levels. First, the State itself is primarily responsible for protecting its own people. Second, if the State is unwilling or unable to protect its people, then the international community is responsible for doing so.

This was affirmed by the UN General Assembly in 2005 in Resolution 60/1, which stated that that “[e]ach individual State has the responsibility to protect its populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity27”. UN member States also declared that “we are prepared to take collective action, in a timely and decisive manner through the Security Council should peaceful means be inadequate and national authorities are manifestly failing to protect their populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity28.”

However, even draft UN Security Council resolutions condemning the violence in Syria and calling for non-military sanctions have been vetoed to date. Four draft resolutions have been vetoed by Russia and China, none of which sought express authorisation for military intervention. The second draft resolution to be vetoed actually stated that “nothing in this resolution authorizes measures under Article 42 of the Charter [i.e. military intervention]29.”

It is no coincidence that the first and only time that R2P has been invoked to justify collective military action through the Security Council against a State was in relation to Libya30. Russia and China consider that regime change in Libya went beyond the authorisation to protect civilians that was given in Security Council Resolution 1973 (2011)31, and are said to be extremely wary that R2P will be abused to effect regime change in the future32.

Resolution 60/1, in which the General Assembly endorsed R2P, only refers to collective action through the Security Council, which is the UN organ with primary responsibility for international peace and security. However, the ICISS report contemplated that, if the Security Council fails to act, the General Assembly might authorise military intervention or regional organisations might intervene with the approval of the Security Council.

The General Assembly has no express powers under the UN Charter to authorise the use of force, in contrast to the Security Council’s powers under Article 42. However, in 1950 the General Assembly adopted Resolution 377(V), referred to as “Uniting for Peace”. Under Resolution 377(V), if the Security Council fails to exercise its primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security due to lack of unanimity amongst permanent members, the General Assembly “shall consider the matter immediately” and may recommend collective measures, including the use of armed force where necessary to maintain or restore international peace and security33.

“Uniting for Peace” and R2P might provide a basis for the General Assembly to make non-binding recommendations for the use of force in Syria, providing greater legitimacy for intervention. However, while the General Assembly has passed resolutions condemning the violence in Syria34, and criticising the Security Council’s inaction35, it has not recommended military intervention or sanctions. This is likely to be partly due to the complexity of the conflict (discussed below), and the difficulty of securing support for intervention from a majority of UN members.

Thus, the UN has been unable to enforce its own demands for an end to the violence in Syria and a political resolution to the conflict. We therefore now examine the legal scope for intervention by third States without UN Security Council authorisation.

D. The Legal Scope for Third State Military Intervention in Syria

The Debate Over the Legality of “Humanitarian Military Intervention”

The situation in Syria rekindled the debate over the legality of “humanitarian military intervention”. That debate was particularly intense following NATO’s intervention in Kosovo in 1999, which NATO undertook without seeking prior UN Security Council authorisation.

The three main positions taken by States and commentators in relation to NATO’s intervention in Kosovo have been reiterated in relation to Syria. They are summarised below:

1. One group built a forceful argument that “humanitarian military intervention” is unlawful because it is contrary to the prohibition against the use of force under Article 2(4) of the UN Charter36. There are only two express exceptions to the prohibition against the use of force: the inherent right of individual or collective self-defence (Article 51, UN Charter); and acts authorized by the Security Council under Chapter VII of the UN Charter.

It is often argued that Article 2(4) of the UN Charter was deliberately drafted to create an absolute rule. This protects State sovereignty, and in particular, protects less powerful States from intervention by more powerful States. Permitting exceptions to the prohibition against the use of force may lead to abuse; such as regime change thinly veiled as “humanitarian” intervention.

2. A second group argued that military intervention in a State to prevent or avert a humanitarian catastrophe is permissible under international law. This position was taken by the UK government, which argued that “force can also be justified on the grounds of overwhelming humanitarian necessity without a UNSCR37”.

Advocates of this position often argue that the protection of fundamental human rights is also vital to the purposes of the UN, as reflected in the preamble to the UN Charter. They also cite potential precedents for “humanitarian military intervention” such as Uganda, Liberia and now Kosovo38.

3. A third group argued that although “humanitarian military intervention” was not permitted under international law as it existed in 1999, the law could or should develop a doctrine of “humanitarian military intervention”. For example, Professor Vaughan Lowe argued that it is: “desirable that a right of humanitarian intervention … be allowed or encouraged to develop in customary international law. No-one, no State, should be driven by the abstract and artificial concepts of State sovereignty to watch innocent people being massacred, refraining from intervention because they believe themselves to have no legal right to intervene.” 39

In August 2013, the USA and the UK threatened to use force against Syria. However, the threat of force was limited to “deterring and disrupting the further use of chemical weapons by the Syrian regime”40 (UK government position). There now seems to be little support for military intervention in Syria similar to that carried out in Kosovo or Libya.

This reluctance to engage militarily in Syria is partly due to the increasing complexity of the conflict, which would make it extremely difficult to ensure that military intervention would make the humanitarian situation better and not worse. Unfortunately, as the Syrian conflict continues the humanitarian situation for many worsens as both sides flout calls to end violations of international law, and extremist groups such as ISIS increasingly use torture41 and disrupt the distribution of aid42.

Criteria for Intervention

If “humanitarian military intervention” can ever be justified, the criteria defining the “exceptional circumstances” in which it may be invoked must be sufficiently clear and narrow to limit the risk of abuse.

The criteria justifying intervention that are often proposed usually include the following:

a) an impending or actual humanitarian disaster, involving large-scale loss of life or ethnic cleansing, which is generally recognised by the international community;

b) last resort – there must be no practicable alternatives to avert or end the humanitarian disaster; and

c) necessary and proportionate use of force – the force used must be limited in time and scope to that which is necessary and proportionate to the humanitarian need.

A further criterion, which is acutely highlighted in the Syrian crisis, is the need for military intervention to be an effective means to provide humanitarian relief. In Syria, it would be very difficult to ensure that military intervention would improve the humanitarian situation in both the short and the longer term.

More limited forms of intervention than the direct use of force in Syria may also pose problems from the perspective of international law. For example, the arming and funding of rebel forces may constitute the threat or use of force or an intervention into Syrian internal affairs43. Permanent aid corridors, as proposed by the French and Turkish governments, would be likely to necessitate military enforcement, involving the threat or use of force.

Despite the ongoing debate concerning “humanitarian military intervention” in international law, one thing is clear: humanitarian assistance itself is lawful under international law. In the words of the International Court of Justice:

“There can be no doubt that the provision of strictly humanitarian aid to persons or forces in another country, whatever their political affiliations or objectives, cannot be regarded as unlawful intervention, or as in any other way contrary to international law.” 44

E. Conclusion

Despite the grievous violations of international law that threaten the lives of many civilians in Syria, there is no consensus of will or legal thinking around “humanitarian military intervention”. Meanwhile, both the Syrian government and the international community appear to be failing in their responsibility to protect the Syrian people, as the conflict leaves many people cut-off from essential humanitarian assistance.

Lack of unity over “humanitarian military intervention” may appear to show the dominance of State sovereignty over human rights. The reality, as reflected in the R2P doctrine, is that the two normally go hand-in-hand because the State should protect and promote the human rights of its people. In exceptional circumstances, there may come a point when “humanitarian military intervention” may be justified, particularly where the use of force can prevent a humanitarian disaster in which the State itself is complicit. However, to reach that point there must be a real prospect of improving and stabilising the humanitarian situation through the use of force. Sadly, if that point ever existed in the Syrian crisis, it may have long been surpassed.

For more information, contact: Natasha Harrington, email: natashaharrington@eversheds.com or harringtonnatasha@gmail.com.

Author’s note:

Since this article was written, ISIS declared a caliphate45 on 29 June 2014 and changed its name to “Islamic State”. The United States launched air strikes against ISIS in Iraq on 8 August 2014, and on 22 September 2014, the United States and its allies also launched air strikes against ISIS in Syria.

The government of Iraq requested assistance to fight ISIS. Therefore, the use of force in Iraq can be justified on the basis that it was carried out with the consent, and at the request, of the Iraqi government.

However, the legality of the air strikes in Syria is the subject of legal debate. Significantly, the United States did not justify intervention on the basis of humanitarian assistance, despite the atrocities committed by Islamic State in Syria. Instead, the United States relies mainly on the collective self-defence of Iraq because ISIS carries out attacks in Iraq from safe havens in Syria. The United States argues that it does not need consent from the Syrian government to carry out air strikes in Syria because that government is “unable or unwilling” to combat ISIS in its territory. The UN Secretary-General also appeared to lend some support to this argument. Reacting to the air strikes in Syria, Ban Ki-moon observed that they were carried out in areas no longer under the effective control of the Syrian government and that they were targeted against extremist groups, which he said undeniably “pose an immediate threat to international peace and security”.

1Advocates for International Development (A4ID) is a charity that helps the legal sector to meet its global corporate social responsibility to bring about world development. It provides a pro bono broker and legal education services to connect legal expertise with development agencies worldwide in need of legal expertise.

2Report of the Secretary-General on the Implementation of Security Council Resolution 2139 (2014), 22 May 2014, UN Doc. S/2014/365, para. 17.

3See Response to Questions from the House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee, Humanitarian Intervention and the Responsibility to Protect, 14 January 2014. Available at: http://justsecurity.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Letter-from-UK-Foreign-Commonwealth-Office-to-the-House-of-Commons-Foreign-Affairs-Committee-on-Humanitarian-Intervention-and-the-Responsibility-to-Protect.pdf (last accessed on 23 May 2014).

4The International Court of Justice considered the relationship between international humanitarian law and international human rights law in Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Advisory Opinion, I.C.J. Reports 2004, p. 136, at p. 178, para. 106. The UN Security Council called on both the Syrian authorities and armed groups to cease all violations of human rights in Security Council Resolution 2139, para. 2.

5Report of the Secretary-General on the Implementation of Security Council Resolution 2139 (2014), 22 May 2014, UN Doc. S/2014/365, para. 3.

6Common Article 3 to the Geneva Conventions 1949; Articles 7 and 14(2) (non-derogation) of the ICCPR; and Article 2(2) of the Convention Against Torture 1984.

7Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arabic Republic, Oral Update, 18 March 2014, pp. 3-4.

8Also known as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria or the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant.

9Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arabic Republic, Oral Update, 16 June 2014, pp. 6-7.

10Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arabic Republic, Oral Update, 16 June 2014, pp. 8-9; also referring to attacks on food distribution points by both government and rebel forces.

11http://www.amnesty.org/en/news/syria-yarmouk-under-siege-horror-story-war-crimes-starvation-and-death-2014-03-10 (last accessed on 19 June 2014).

12Report of the Secretary-General on the Implementation of Security Council Resolution 2139 (2014), 22 May 2014, UN Doc. S/2014/365, para. 12.

13Open Letter: Let us Treat Patients in Syria, The Lancet, 16 September 2013; http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(13)61938-8/fulltext (last accessed on 26 May 2014).

14Physicians for Human Rights calculates that Syrian government forces are responsible for 90% of 150 reported attacks on hospitals. http://physiciansforhumanrights.org/press/press-releases/new-map-shows-government-forces-deliberately-attacking-syrias-medical-system.html (last accessed on 26 May 2014).

15Report of the Secretary-General on the Implementation of Security Council Resolution 2139 (2014), 23 April 2014, para. 42. http://www.msf.org/article/five-msf-staff-held-syria-released (last accessed on 19 June 2014).

16The International Independent Commission of Inquiry on Syria cites removal of essential medical and surgical supplies from aid convoys, resulting in scarcity of the most basic medical necessities such as syringes, bandages and gloves. Oral Update, 16 June 2014, p. 7, para. 46 and p. 8, para. 51.

17Report of the Secretary-General on the Implementation of Security Council Resolution 2139 (2014), 23 April 2014, para. 52.

18Report of the Secretary-General on the Implementation of Security Council Resolution 2139 (2014), 23 April 2014, para. 35.

19Report of the Secretary-General on the Implementation of Security Council Resolution 2139 (2014), 22 May 2014, UN Doc. S/2014/365, para. 31. If the fighting continues, there is a risk that border-crossings with Turkey could be permanently closed, compromising the delivery of aid to approximately 9.5 million people. Syria Needs Analysis Project, Potential cross-border assistance from Turkey to Syria, April 2014. Available at: http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/potential_cross_border_assistance_from_turkey_to_syria_0.pdf (last accessed on 23 May 2014).

20Open letter to the UN Secretary General, Emergency Relief Coordinator, the heads of UNICEF, WFP, UNRWA, WHO, and UNHCR, and UN Member States, 28 April 2014. Available at: http://www.ibanet.org/Article/Detail.aspx?ArticleUid=73b714fb-cb63-4ae7-bbaf-76947ab8cac6 (last accessed on 23 May 2014).

21Under Chapter VII, measures to enforce decisions of the UN Security Council may be adopted.

22Report of the Secretary-General on the Implementation of Security Council Resolution 2139 (2014), 22 May 2014, UN Doc. S/2014/365, para. 51.

23http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/24/world/middleeast/un-chief-urges-aid-deliveries-to-syria-without-its-consent.html?_r=0 (last accessed on 20 June 2014).

24Ibid

25Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arabic Republic, Oral Update, 16 June 2014, p. 2, para. 4.

26Provisional record of the meeting of the UN Security Council on 22 May 2014, UN Doc. S/PV.7180.

27UN General Assembly Resolution 60/1, 2005 World Summit Outcomes, para. 138. UN Doc. A/RES/60/1.

28Ibid., para. 139.

29Draft Resolution proposed by 19 States, dated 4 February 2012, UN Doc. S/2012/77.

30See Resolution 1973 (2011), UN Doc. S/RES/1973 (2011).

31Resolution 1973 authorised UN Member States “to take all necessary measures… to protect civilians and civilian populated areas under threat of attack in the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya… while excluding a foreign occupation force of any form on any part of Libyan territory”. UN Doc. S/RES/1973 (2011), 17 March 2011, para. 4.

32For a summary of these concerns, see Z. Wnqi, Responsibility to Protect: A Challenge to Chinese Traditional Diplomacy, 1 China Legal Science 97 (2013).

33Uniting for Peace has only been used as the basis for the UN General Assembly to recommend military intervention on one occasion, in 1951 in relation to Korea (Resolution 498(V)).

34Resolution 66/253 A (21 February 2012), UN Doc. A/RES/66/253.

35Resolution 66/253 B (7 August 2012) UN Doc. A/RES/66/253 B, preamble.

36Article 2(4) of the UN Charter provides that “All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations.” See for example, Brownlie & Apperley, Kosovo Crisis Inquiry: Memorandum on the International Law Aspects, (2000) 49 Int’l & Comp. L.Q. 878.

37Statement of the UK’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations to the Security Council on 24 March 1999, cited in Response to Questions from the House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee, Humanitarian Intervention and the Responsibility to Protect, 14 January 2014. Available at: http://justsecurity.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Letter-from-UK-Foreign-Commonwealth-Office-to-the-House-of-Commons-Foreign-Affairs-Committee-on-Humanitarian-Intervention-and-the-Responsibility-to-Protect.pdf (last accessed on 23 May 2014).

38See, for example, Greenwood, Humanitarian Intervention: The Case of Kosovo, 2002 Finnish Yearbook of International Law, p. 141.

39Lowe, International Legal Issues Arising in the Kosovo Crisis, (2000) 49 Int’l & Comp. L.Q. 934, at p. 941.

40Guidance Note, Chemical weapon use by Syrian regime: UK government legal position, 29 August 2013, para. 4.

41Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arabic Republic, Oral Update, 16 June 2014, p. 6, para. 40.

42The Assessment Capacities Project, Regional Analysis Syria – Brief, 3 June 2014, p. 2.

43Article 2(7) of the UN Charter prohibits intervention in matters “essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any state”. See Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v. United States of America). Merits, Judgment. I.C.J. Reports 1986, p. 14, at p. 118, para. 228 and p. 124, para. 242.

44See Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v. United States of America). Merits, Judgment. I.C.J. Reports 1986, p. 14, at p. 124, para. 242.

45 A form of Islamic political-religious leadership which centres around the caliph ("successor”) to Muhammad.