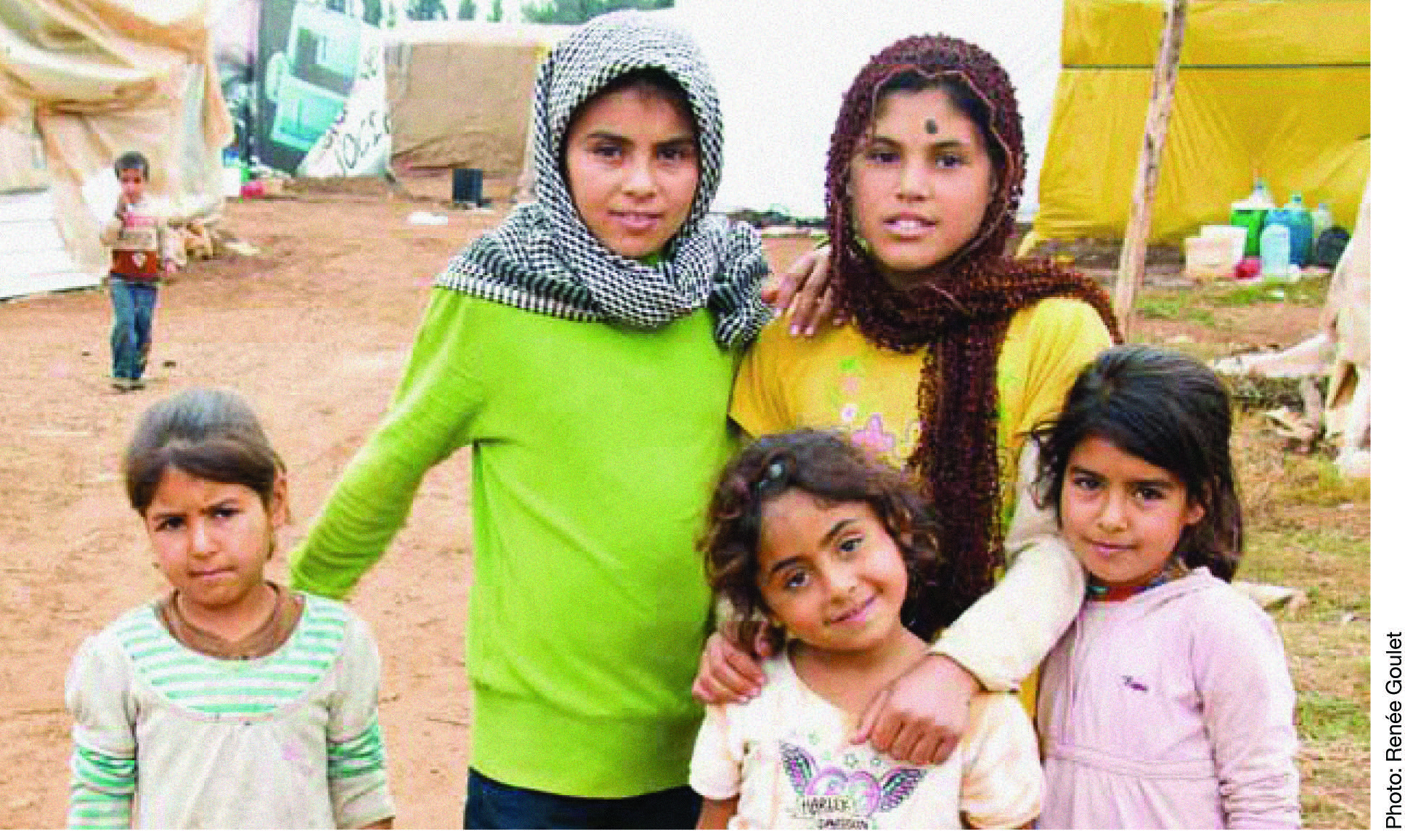

Meeting cross-sectoral needs of Syrian refugees and host communities in Lebanon

By Leah Campbell

By Leah Campbell

This summary is based on a longer written case study written by Leah Campbell for CaLP1. A video presenting the programme is also available2. If you would like more detail on the case study, particularly the context, decision to support host communities as well as refugees, protection impacts and monitoring strategy, please consult the longer case study.

Introduction

In complex crises such as the Syrian conflict and resulting regional displacement, affected populations have an equally complex set of needs, which do not fit neatly into the current architecture of humanitarian response. Refugees who have fled their homes with few physical or social assets, require support which considers their needs holistically. The rise of cash-based responses in the humanitarian sector is in part due to the flexibility of this modality to meet a diversity of needs through one intervention. Nevertheless, many cash-based responses remain sector-specific, with organisations providing cash for rent or vouchers for specific food items.

Cross-sector cash programmes (also called multi-sector) address need across the boundaries of sectors and clusters. Providing cash which is intentionally cross-sectoral places decisions in the hands of affected households, who are empowered to make choices and prioritise needs.

IRC’s programme

Between February and October 2013, the International Rescue Committee (IRC) implemented an unconditional cross-sector cash programme in Akkar, north Lebanon. The programme provided monthly cash assistance for a time-limited period of 4-6 months to 700 Syrian refugee and 425 vulnerable Lebanese households. Heads of households, most of whom were women, received an ATM card which was reloaded monthly with $200 USD. The objective of the programme was to improve living conditions and allow recipient households to meet basic needs, which were diverse and changing. It aimed to reduce negative coping strategies, particularly for women, and reduce social tensions between Syrian and Lebanese vulnerable households.

IRC undertook gender based violence (GBV) and livelihoods assessments in order to understand the needs and situation of the affected population, particularly the risks for women and girls and the income opportunities available. These assessments found that Syrian refugees and Lebanese host communities were under severe financial strain and relying increasingly on negative coping strategies. Rented accommodation was hard to find and the capacity of communities to host refugees was diminishing. The influx of refugees had a significant impact on the income and expenditure of both refugees and host communities. Daily wages were reduced by up to 60% and as a result, many families couldn’t meet basic needs. Almost all were resorting to incurring debt to meet their expenses, alongside negative coping strategies, such as selling assets/in-kind assistance and sending children to work. Providing assistance to both vulnerable Syrian and Lebanese households can help to mitigate the tensions caused by these difficult economic circumstances by addressing the needs of both groups transparently, focusing on vulnerability rather than nationality.

Establishing the value of the transfer was a challenge, and required consideration of needs across multiple sectors, differences between urban and peri-urban areas, and harmonisation between multiple agencies providing similar, or sector-specific, cash assistance. The value of $200 USD was based on minimum expenditure basket calculations led by the Cash Working Group in Lebanon. It is estimated to be equivalent to 40-50% of basic needs expenses for a family of six. This value was transferred to the programme’s selected recipients through reloadable ATM cards, which were found to offer the least risk and highest flexibility of the options available. Less than 3-6% of programme participants had previous experience of using an ATM card. However, after a 1 hour training and practice session, 59-71% were able to use the card without assistance and almost all were able to use the card with the assistance of family or friends. The programme did find that ATM cards are not the most suitable option for the elderly and those with disabilities.

IRC identified potential affected vulnerable populations via referrals from a variety of sources and then conducted assessments exploring various vulnerability criteria, including dependency ratio, assets, food consumption and income-expenditure gap. Following interviews and observations to assess regular income and expenditure, food consumption and coping strategies, households were ranked and the most vulnerable selected as programme recipients. Those households were then invited to an information session to receive their ATM card and training. IRC operated a hotline to address questions and problems for card users, and acted as an intermediary between recipients and the card provider.

IRC’s initial vulnerability criteria prioritised women-headed households, many of whom had little experience managing household budgets. Funds were always provided to the head of household. In an effort to extend the long-term impact of the programme, IRC piloted financial literacy training alongside the cross-sector cash programme. This training, delivered over six weeks, provided micro-level budgeting and debt management support in conjunction with IRC’s Women’s Protection and Empowerment team. Increasing women’s self-reliance and capacity to maximise available resources is particularly important, and can mean reduced exposure to negative coping strategies and GBV.

Due to the growing need in Lebanon, IRC has expanded its cross-sector cash programme as well as other related programmes, including financial literacy. IRC is also expanding its livelihoods assistance programming and will offer conditional assistance in the form of cash for work and cash for training.

Monitoring impact

IRC conducted post-distribution monitoring (PDM) through a survey with different recipients every 2-3 months. This survey looked at satisfaction with modality, ability to access funds, impact of the assistance on coping ability and security concerns. Price monitoring was also conducted at selected shops to monitor changes (over time and between Syrian and Lebanese shoppers) in market prices of a basket of frequently purchased items.

IRC conducted post-distribution monitoring (PDM) through a survey with different recipients every 2-3 months. This survey looked at satisfaction with modality, ability to access funds, impact of the assistance on coping ability and security concerns. Price monitoring was also conducted at selected shops to monitor changes (over time and between Syrian and Lebanese shoppers) in market prices of a basket of frequently purchased items.

Measuring impact of cash assistance can be complex, particularly when multiple organisations are providing cash. When the programme is cross-sector, it can be a challenge to see sector-specific impacts. IRC’s PDM gives a general understanding of how the cash is being used and what potential impacts it is having. For example, the PDM surveys track the percentage of recipients reporting that their main expenditure of IRC cash assistance is food, rent, healthcare or debt repayment. Though these figures are general, they give a clear indication that needs are varied and IRC’s single programme is able to support a diversity of vulnerable households. IRC also examined the percentage of recipients who report an increase in a variety of wellbeing indicators. For example, IRC PDM showed that, on average, 52.5% of recipients report they are “able to provide larger portions of food” to their family, and 72.5% report being able to “eat higher quality food” as a result of IRC’s cross-sector cash support. These nutrition-related impacts are alongside other sector-specific impacts (“better health conditions”, “improved shelter/accommodation”) as well as cross-cutting impacts (“reduction in household debt”).

Challenges and lessons learned

Three key challenges faced during implementation of this programme were that of dependency, funds not being spent as expected, and inflexible coordination mechanisms. The risk of dependency is amplified when supporting needs in multiple sectors. IRC’s cash assistance was designed to provide short-term support to vulnerable refugees and Lebanese households. Though recipients were informed about the nature and timeframe of the support so they could make informed decisions, need is high and humanitarian response in the region is underfunded. As for how funding is spent, the challenge of cross-sector programming is that the choice of how funds are to be spent lies with the affected household. This does not fit well within existing humanitarian funding and reporting mechanisms, which expect funds to be allocated to specific sectors and for decisions about allocation to be made in advance. Programme monitoring relies on recipients being honest and accurate, which adds to the challenge. IRC built strong assessment and monitoring systems and trusted in these. Recognising the importance of coordination to ensure harmonisation and avoid duplication where possible, IRC sought to participate in coordination mechanisms. However the existing coordination structure does not appear flexible enough to accommodate a cross-sector programme effectively. IRC’s first monitoring results showed that for most, food was the main expenditure. As a result, IRC participated in the Food Security Working Group. However, on further monitoring the amount spent on rent was higher than that for food and in most cases, households reported that they spent the funds in multiple sectors. As it is impractical to participate in every sector working group, and how funding is used by affected people changes month to month, it is unclear how actors such as IRC should participate in the coordination system in Lebanon.

Several lessons emerge from IRC’s cross-sector cash programme in Lebanon. Firstly, the humanitarian system must be more flexible, and let go of the need to control how cash transfers are allocated by households. It needs to trust crises-affected people to make decisions for their own households. Secondly, it needs to find ways to adapt planning and coordination mechanisms to accommodate cross-sector programming, rather than attempting to force a square peg into a round hole. Thirdly, agencies should recognise that though cash can meet a variety of needs, not everything can or should be monetised. Additionally, ATM cards will not work for every household. Finally, IRC’s programme highlighted the importance of working holistically and in partnership with colleagues. Specific lessons on working with local municipalities, banks and protection colleagues can be found in the full case study.

For more information on this case study, contact Leah Campbell l.campbell@alnap.org

Recommended further reading

Adeso (2013). Adeso workshop report: Multi Sectoral Cash Transfer. Nairobi

Afghanistan Cash and Voucher Working Group (2013) Cash transfer programming in complex emergencies: Technical Operational Guidelines for Afghanistan http://afghanctp.org/Content/Media/Documents/Annex-15CashTransfersTechnicalOperationalGuidelines-Afganistan-309201352515963553325325.pdf

CaLP (2011) Making the Case For Cash: A field guide to advocacy for cash transfer programming http://www.cashlearning.org/downloads/resources/tools/CaLP_Making_the_case_for_Cash_v2-FINAL_screen.pdf

Midgley, T. & Eldebo, J. (2013). World Vision. Advocacy Report. Under Pressure: The Impact of the Syrian Refugee Crisis on Host Communities in Lebanon