Non-food cash voucher programme for IDPs in Northern Syria

By an international NGO

Written April 2014

The war in Syria is now in its third year and having displaced over four million Syrians internally - with over 2 million fleeing their country to Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq and Turkey - there is no end in sight. In Northern Syria, over 200,000 Syrians are living in internally displaced population (IDP) camps, namely Atmeh, Qah, Karameh, Aqqrabat, Bab-Al- Hawa and Al-Salham, while 35,000 people are living in non-camp settings in villages.1

Provision of assistance to such a large number of displaced people in camps with inadequate infrastructure is a challenge to humanitarian organisations. Most of the emergency response involves in-kind distributions of food and nonfood items. These interventions have been effective in saving lives and preventing a further deterioration in the humanitarian situation. However, the approach has several drawbacks, including the fact that it is a huge logistical burden and time consuming activity -from procurement to stocking and transporting commodities to distribution. This is made all the more difficult in conflict affected areas. Also, it disempowers the affected population as it does not provide them with the ability to decide what commodities they want or prefer. With the aim of mitigating these problems, a pilot voucher programme was designed and implemented by an international non-governmental organisation (INGO) in one of the IDP camps.

Overview of voucher programme

This involved voucher distribution and the arrangement of two market days at which to spend the vouchers. The programme was implemented over one month. The programme was informed by a needs assessment and market assessment (1 week) by the INGO, followed by vendors’ selection and beneficiary registration before implementation.

The needs assessment involved four focus group discussions (FGD) to understand the IDPs’ need for non-food items. The FGDs were conducted with men, women, young boys and young girls. They indicated that the top three priorities were hygiene items, clothing, and kitchen items. The preference was for Syrian made items that met their social and cultural values, such as scarves, long skirts, specific shampoos and detergents. Based on the identified needs, market prices were collected for the major items and maximum prices were agreed with the vendors that would apply for the two market days. This was undertaken to protect the value of the vouchers that was based on the findings of the market assessment. Findings from the market and price assessments were shared with both vendors and beneficiaries. The arrangement was governed by a signed memorandum of understanding with the INGO office to keep the price as agreed or constant. An exception was if vendors wished to sell at a lower rate (while maintaining quality) to attract buyers, they were free to do so. Beneficiaries had also the right to negotiate on price in order to buy more items. Either way, better deals could be made for the same quality of product. The agreements also included clauses on the respect of humanitarian principlesand using an agreed upon stable exchange rate of Syrian Pound (SP) to United States Dollar (USD). Field monitoring and support was undertaken by the field staff.

Vendors were identified from nearby Syrian cities and their capacity to meet the identified needs was assessed. Twelve vendors were selected to participate in the market day to create enough competition to lower the prices, however only seven were able to participate. The five vendors who did not participate pulled out at the last minute; no reasons were given but may have been due to security issues or lack of sufficient stock.

Implementation

A total of 420 IDP households benefited from the pilot programme in the camp. Each household was provided with 12 vouchers, worth 12,000 SP (69 USD). The vouchers had denominations of 3,000, 1,500, 600 and 300 SP, to provide more flexibility in shopping for smaller or bigger items.

Two market days were selected and agreed on with the beneficiaries and vendors. The vendors trucked their goods to the camps on the agreed dates and the camp leaders were responsible for securing a space for the market place and for crowd control. The INGO staff monitored all activities during both market days and provided guidance when needed. At the end of the first market day, the vendors packed their remaining items and carried them back to their home towns. With a better understanding of what the IDPs wanted to buy, the vendors increased the amount and the diversity of the items they brought to the second market day.

Feedback

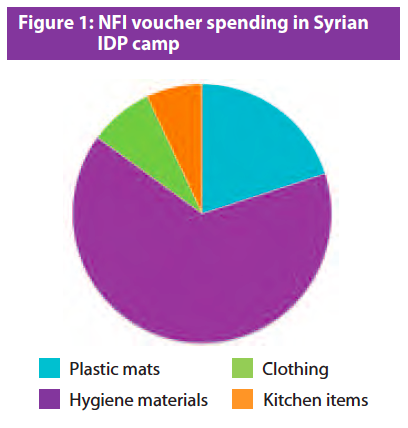

A rapid post distribution survey was conducted which found that all 420 households had spent 100% of their vouchers. The top three purchased commodities were hygiene materials, plastic mats, and clothing (see Figure 1). Beneficiaries indicated that they were highly satisfied with the programme and commented that it was the first time in two years that they were able to do their own shopping. They were pleased to regain their ability to make their own decisions about what to purchase for their families. However they commented that the price of goods had risen sharply over the past years due to loss of SP value. Some of the beneficiaries observed that prices were three times higher compared to what they used to pay in their hometowns a couple of years ago. Overall, the pilot programme was appreciated by the beneficiaries because it gave them the opportunity to choose goods depending on their needs, the goods were from Syria, the suppliers were Syrian, and the response time between the need assessment and the market days was very short. There was no security problem and no complaints were registered from the beneficiaries or the vendors. To date (May 2014), the programme has not been repeated but the team is preparing to scale up the voucher system to other camps.

Conclusions

The voucher programme was a speedy response to the camp IDPs and the best way to address their basic needs. Satisfaction among the beneficiaries was very high mainly due to a high level of participation (involving the beneficiaries) during the needs assessment, the market assessment and consultations at various levels. Also, use of local suppliers (Syrian) who are known by the community and part of the same culture helped to supply materials that fit to the context and cultural values of the IDP’s. The voucher system has proven to be applicable in an IDP camp setting. It was implemented quickly in an emergency context to address basic needs of the IDP’s, and carried lower risks due to the requirement for less logistic activities and low visibility of the approach.

Above all, the voucher approach empowers beneficiaries and respects their dignity as it gives them the right to choose how they meet their needs, which is fundamental principle of the humanitarian charter.

1Turkey and Syrian refugees: the limits of hospitality. http://www.brookings.edu/research/reports/2013/11/14-syria-turkey-refugees-ferris-kirisci-federici