The Syria Needs Assessment Project

By Yves Kim Créac'h and Lynn Yoshikawa

By Yves Kim Créac'h and Lynn Yoshikawa

Yves Kim Créac'h is currently the Project Lead for the SNAP Project. He is a seasoned humanitarian worker, with 15 years of experience in the humanitarian field at senior level, with focus on strategy formulation, management of large scale humanitarian operations in complex emergencies and policy influencing. He’s one of the founders of the ACAPS project.

Lynn Yoshikawa is an analyst with the Syria Needs Analysis Project (SNAP) based in Amman, Jordan. She has worked in the humanitarian sector for over 10 years in Afghanistan, Southeast Asia, the Middle East and in headquarters, primarily focused on policy research.

A special acknowledgement goes to Nic Parham, former SNAP Project Lead, whom with his team has established the SNAP Project and developed a totally new approach to information within the humanitarian system.

A special acknowledgement goes to Nic Parham, former SNAP Project Lead, whom with his team has established the SNAP Project and developed a totally new approach to information within the humanitarian system.

A year after the start of the Syrian crisis, ACAPS1 was approached by a range of donors to consider a small project to bring together all existing information concerning the humanitarian situation of those affected by the crisis. Many organisations (humanitarian, governmental, media etc.) were reporting on elements of the crisis, usually specific to a particular problem in a particular age-group or in a particular country, such as shelter for refugees in Lebanon or food for Palestinians in Syria. With UNHCR country offices responsible for the coordination of the response in refugee-hosting countries, (the exception being Turkey where government took responsibility for coordination), and OCHA responsible for coordination in Syria, obtaining a holistic picture of the situation was challenging. It was also impossible to determine what was known and what the gaps in information were, due to the sensitivities of reporting on the humanitarian situation, particularly by agencies working from Damascus, as well as those working cross-border without registration. Most actors engaged in the Syria conflict response agreed that there was an incoherent picture of the humanitarian situation in Syria and neighbouring countries, and how dynamics in Syria affected host countries and vice versa. Humanitarian stakeholders had an insufficient shared situation awareness, and there were significant and persistent inconsistencies in reports on the actual number of affected Syrians both inside and outside the country, the movement and flows of populations, general humanitarian needs and the longer-term impact on infrastructure and livelihoods in-country. This problem was further exacerbated by the sensitivities associated with information management while ensuring continued access to the affected population. It was for this reason that SNAP (the Syria Needs Analysis Project) was born in December 2012.

SNAP was initially conceived as a two to three person project with some remote support from the ACAPS and MapAction2 headquarters, aimed at improving the humanitarian response by creating a shared situational awareness. Using ACAPS’ skills and experience in the analysis of secondary data, SNAP would seek to build trust with sufficient stakeholders in the region so as to gain access to as much information as possible then, bearing in mind the various levels of confidentiality by which information is shared, create products to inform the strategic decisions to be made by the humanitarian community. As such, SNAP created the RAS (Regional Analysis of Syria), which was initially monthly and would cover both humanitarian issues in Syria and neighbouring countries. In addition, due to increased demands from humanitarian stakeholders, thematic reports of governorate profiles3, cross border access analysis4, etc. were produced as well. Within a month of starting the project, SNAP took advantage of an opportunity to support a joint multi-sectoral needs assessment in northern Syria (J-RANS). By providing the bulk of the technical capacity (analytical skills, geographical information system (GIS) and assessment expertise), SNAP facilitated the process for the humanitarian community to gain the first comprehensive overview of needs in northern Syria. As a result, SNAP expanded its objectives to include the provision of support to coordinated assessment initiatives and staffing increased accordingly, with additional needs assessments facilitated in Dar’a and Quneitra governorates in southern Syria.

SNAP was initially conceived as a two to three person project with some remote support from the ACAPS and MapAction2 headquarters, aimed at improving the humanitarian response by creating a shared situational awareness. Using ACAPS’ skills and experience in the analysis of secondary data, SNAP would seek to build trust with sufficient stakeholders in the region so as to gain access to as much information as possible then, bearing in mind the various levels of confidentiality by which information is shared, create products to inform the strategic decisions to be made by the humanitarian community. As such, SNAP created the RAS (Regional Analysis of Syria), which was initially monthly and would cover both humanitarian issues in Syria and neighbouring countries. In addition, due to increased demands from humanitarian stakeholders, thematic reports of governorate profiles3, cross border access analysis4, etc. were produced as well. Within a month of starting the project, SNAP took advantage of an opportunity to support a joint multi-sectoral needs assessment in northern Syria (J-RANS). By providing the bulk of the technical capacity (analytical skills, geographical information system (GIS) and assessment expertise), SNAP facilitated the process for the humanitarian community to gain the first comprehensive overview of needs in northern Syria. As a result, SNAP expanded its objectives to include the provision of support to coordinated assessment initiatives and staffing increased accordingly, with additional needs assessments facilitated in Dar’a and Quneitra governorates in southern Syria.

Concurrent to this support to primary data collection in northern Syria, SNAP worked to develop relationships with humanitarian actors throughout the region. Linking quickly with UNHCR and some key non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in Lebanon and Jordan proved essential in understanding the refugee context. It quickly became clear that few organisations made public their most useful and interesting data due to operational sensitivities, particularly with host governments and at times, with donors. Thus SNAP strove to build personal relationships with key stakeholders across the humanitarian community which necessitated a further expansion, deploying additional analysts in Jordan and Turkey and expanding the core team in Lebanon. Over the first six months of the project, the SNAP team grew from three to nine, with further expansion to 20 staff planned in 2014.

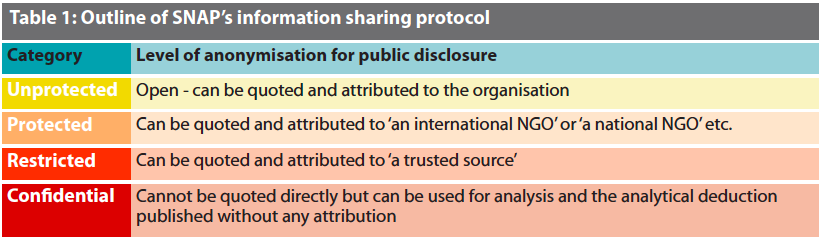

Key to accessing data and information in the Syrian context has been confidentiality; many organisations are sensitive about details of their operations – particularly in Syria, due to the complex nature of the crisis and the need to work in areas under control of the various parties to the conflict. SNAP quickly developed a simple information sharing protocol to facilitate the sharing of information and clarify the level at which it could be made public (see Table 15).

SNAP also aims to source and hyperlink all information in the reports to enable readers to further investigate and judge the reliability of the source. However, where organisations are reluctant to be associated by name with information sharing, two levels of general sourcing are used: a) ‘an INGO’ or a UN agency’ etc. or b) ‘a trusted source’. Where partners share information on the understanding that it is not shared publicly, SNAP uses it to triangulate data from other sources and to inform general analysis. ‘Off the record’ conversations with experts in a particular field are useful as they may either confirm or question information from other sources, highlight issues of which we are unaware, assist us in reprioritising issues, as well as contribute to our overall understanding of the situation. Support to assessment initiatives across the region also contributes to SNAP’s overall aim, by increasing the quality of timely data available.

The absence of systematically collected, reliable information from Syria also presents a challenge in deciding the level of information that is ‘good enough’. When information is scarce, a particular piece of information can seem especially valuable, but if it is highly specific (such as information on a particular village) and no comparable information is available, it is misleading to include it in a report as it gives the impression that the information is the most important piece of information. For example, credible and reliable information might be available that village X has suffered repeated aerial bombardment and that food is scarce and insufficient for the population. Without information on the situation in other villages in the area, reporting this information may give the impression that village X is the only part of the district witnessing direct attacks and in need, or that it is the most in need.

Collecting information on nutrition in the Syrian context has been particularly challenging due to the need for specialised training of enumerators and achieving proper sampling in a context where population estimates and displacement are highly dynamic. In the second iteration of the J-RANS in April 2013, SNAP included nutrition in the multi-sectoral assessment, however, it was found that enumerators lacked adequate training properly to distinguish between food security and nutrition needs. Hence, the results blurred the lines between the two sectors, and in subsequent assessments, nutrition was not included as a standalone sector.

Underpinning SNAP’s work is the view that information is never perfect and thus we strive to give analysis deemed ‘good enough’ to enable decisions to be based on the best possible evidence. To this end, SNAP seeks to highlight information gaps and the most recent information while giving a sense of the reliability of the information.

Various challenges have arisen: the sheer number of actors in the crisis; the significant part played by actors who do not link to the international humanitarian architecture (such as diaspora, armed groups, community-based and faith-based organisations, etc.); the political sensitivity of headline numbers; the operational sensitivity of information in Syria (especially regarding access and border crossings); lack of access to and information on certain areas within Syria; lack of information on certain groups and sectors; the dynamic nature of the crisis and thus humanitarian decision-makers’ information needs.

SNAP thus adopts a graduated approach to information collection that starts with a daily trawl of the internet. Each piece of information is captured in a spreadsheet which categorises it according to geographic location, affected group, sector, date, type of information (conflict; needs; response etc.), source, etc. The data can then be filtered by sector and location, say health in Ar-Raqqa governorate, to view all the recent/new information on health in that governorate. Combined with unpublished information gathered directly from other sources, this gives a basis for identifying key issues (or gaps in knowledge) of the situation. Weekly team analysis sessions help the team identify issues for further investigation/data collection. Prior to the drafting of a report, SNAP invites specialists in particular fields, and some general humanitarian analysts, to help analyse the issues that have been identified as particularly important, and that will be highlighted in the report.

One of SNAP’s strengths is that it is independent – in that, not being an operational response organisation, SNAP has no cause to promote the needs in one sector, location, or of one group over another. That all SNAP’s analysts are generalists also reduces this risk – although it does necessitate the involvement of specialists in the analysis process. Not being operational in Syria also means that SNAP can publish information with which the Government or opposition might disagree, although the need to ensure that our publications do not compromise the safety and security of staff in Syria or jeopardise humanitarian operations remains paramount.

A second strength is that SNAP has no mandate for coordination or information management in a specific context and can produce independent analysis of the whole humanitarian situation based almost entirely on information provided by others. Many organisations see this as useful, as it gives them evidence from a trusted source to support interventions and appeals for donor funding. UNHCR in Lebanon and Jordan also see SNAP’s products as contributing to their effort to coordinate the response. Coordination with OCHA is more of a challenge due to the constraints faced by Damascus-based organisations on publicly sharing information and analysis, since most information coming out of Damascus-based operation have to be approved by the Government of Syria.

A growing part of SNAP’s focus is direct support to humanitarian needs assessments, especially within Syria but also in Jordan and Lebanon. SNAP only supports initiatives that are coordinated with multiple actors such as the J-RANS6 and SINA7 exercises in Syria and the MSNA8 in Lebanon. As SNAP’s added value is in secondary data collation and analysis, we are working increasingly closely with other specialist primary data collection organisations such as REACH. Further to that, in both Turkey and Jordan, SNAP has provided a number of assessment trainings to the humanitarian communities and intends to expand this service that would include in the future, in-depth trainings in specific topics, such as analysis or devising sampling methodologies.

Monitoring the use of SNAP’s analysis and the catalytic effect the project has had on assessment coordination and information sharing is one of the more challenging parts of the project. An independent evaluation undertaken nine months into the project found that SNAP “offered significant value to the humanitarian community in strengthening the targeting of assistance and in making an important contribution to a shared situation awareness” and that its relevance “stemmed from its ability to fill critical gaps in the information and analysis of the humanitarian community”. While anecdotal evidence suggests many donors and NGOs, both international and national, use and value SNAP products, their value to the humanitarian community within Syria, especially the Humanitarian Country Team, remains unclear.

Over the first 15 months of SNAP, it has become clear that there is a huge appetite for independent analysis and a consolidated report on the overall humanitarian situation, although views differ as to the level of detail required. SNAP has also proved that it is possible to gain the trust of a variety of organisations, UN, NGO, faith-based etc., and gain access to otherwise confidential information. However, to do this takes both time and staff and it is a constant challenge to ensure that the value of SNAP’s products is worth the cost of the project.

For more information, contact: Yves Kim Créac'h, SNAPLead@acaps.org

1 ACAPs is a consortium of NGOs created at the end of 2009 to strengthen assessment and analysis methodologies as well as providing surge capacity for the IASC in time of crisis

3 For example, see latest Idlebl governorate profile at http://www.acaps.org/en/pages/syria-snap-project

4 For example, see: http://www.acaps.org/reports/downloader/cross_border_movement_of_goods/67/syria

5 The more detailed SNAP information sharing classification system is available at http://www.acaps.org/en/pages/syria-snap-project

6 J-RANS: Joint Rapid Assessment of Northern Syria

7 SINA: Syria Integrated Needs Assessment

8 MSNA: Multi-Sector Need Assessment

English

English Français

Français Deutsch

Deutsch Italiano

Italiano Español

Español