WFP’s emergency programme in Syria

By Rasmus Egendal and Adeyinka Badejo

Rasmus Egendal has more than 20 years of experience in international development and humanitarian aid assistance. Currently he is serving as Deputy Regional Emergency Coordinator for WFP’s Emergency Response in Syria and neighbouring countries.

Rasmus Egendal has more than 20 years of experience in international development and humanitarian aid assistance. Currently he is serving as Deputy Regional Emergency Coordinator for WFP’s Emergency Response in Syria and neighbouring countries.

Adeyinka Badejo joined WFP in 2001 and is currently Deputy Country Director for WFP in Syria. Previously, she served as a WFP Programme Officer in Afghanistan, Zimbabwe, Sudan and in Rome and undertook field work in Pakistan, Palestine, Tanzania, Egypt, Cambodia, Nepal and Afghanistan.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Sarah Gordon-Gibson, Regional Programme Manager, WFP Syria and neighbouring countries; Lourdes Ibarra, Head of Programme, WFP Syria; Yasmine Lababidi, Nutrition Programme Assistant; and Nicoletta Grita, Reports Officer.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Sarah Gordon-Gibson, Regional Programme Manager, WFP Syria and neighbouring countries; Lourdes Ibarra, Head of Programme, WFP Syria; Yasmine Lababidi, Nutrition Programme Assistant; and Nicoletta Grita, Reports Officer.

Overview

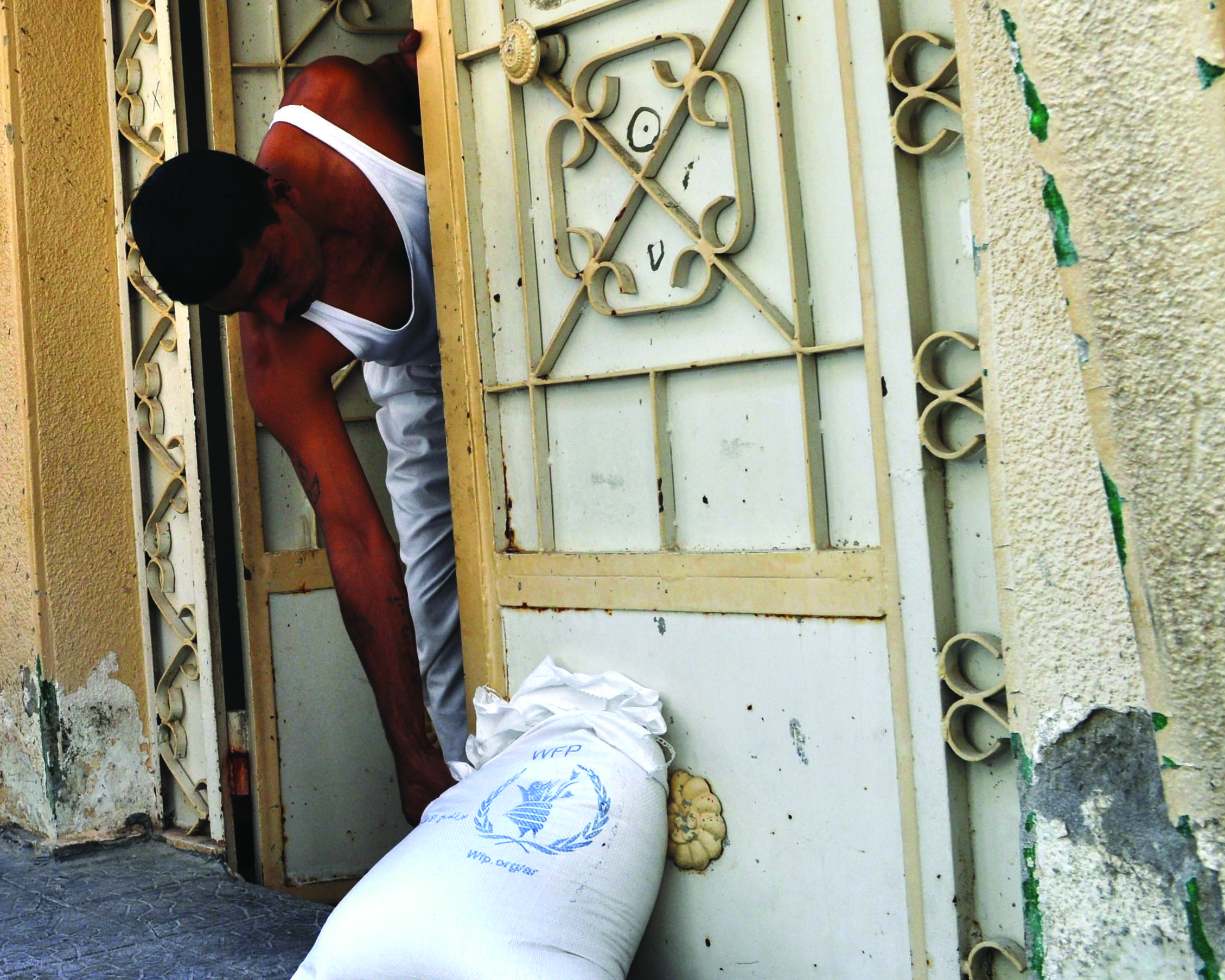

WFP has had a continued presence in Syria for almost 50 years, providing more than US$500 million worth of food assistance into the country through development and emergency operations. Prior to the current conflict, WFP, together with its partner organisation the Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC), responded to emergency food needs following consecutive droughts, assisted in the implementation of school feeding programmes and provided assistance to Iraqi refugees seeking sanctuary in Syria. In October 2011, WFP launched an emergency operation to provide relief food assistance to affected families, in what was then a localised conflict. Initially targeting 50,000 beneficiaries, the operation was rapidly scaled up as the conflict spread over the following months. Over time, WFP modified the composition of the food basket, in response to changes in the availability and accessibility of individual commodities. A blanket supplementary feeding programme (BSFP) for young children was developed following concerns over declining nutritional indicators. Ready-to-eat food rations were provided for newly displaced families without access to alternative sources of food or cooking facilities.

In 2013, WFP gradually scaled up its response, reaching close to 3.4 million beneficiaries across all 14 Syrian governorates. WFP expanded its network of local non-governmental organisations (NGOs) beyond SARC to enhance its capacity and reach to meet rapidly growing needs. As of June 2014, a total of 27 partners support the delivery and distribution of WFP food assistance. These include SARC, 25 local NGOs, and one international NGO (the Aga Khan Foundation) working in Hama governorate. Through their long established presences and extensive local networks, WFP’s partner organisations, local authorities and community leaders mobilised to help ensure and organise the safe delivery of assistance. Each partner has been selected to ensure their compatibility with WFP’s mandate and with the principles of the UN Global Compact1 and the WFP Code of Conduct.

In 2013, WFP gradually scaled up its response, reaching close to 3.4 million beneficiaries across all 14 Syrian governorates. WFP expanded its network of local non-governmental organisations (NGOs) beyond SARC to enhance its capacity and reach to meet rapidly growing needs. As of June 2014, a total of 27 partners support the delivery and distribution of WFP food assistance. These include SARC, 25 local NGOs, and one international NGO (the Aga Khan Foundation) working in Hama governorate. Through their long established presences and extensive local networks, WFP’s partner organisations, local authorities and community leaders mobilised to help ensure and organise the safe delivery of assistance. Each partner has been selected to ensure their compatibility with WFP’s mandate and with the principles of the UN Global Compact1 and the WFP Code of Conduct.

Considerable efforts to strengthen local capacity have been made throughout 2013 including supplying crucial equipment and providing training on warehouse management, safe distribution practices, and programme monitoring. While allocation to partners varies on the basis of needs, capacity and access, on average approximately 55% of total food rations are allocated to SARC, while the remaining 45% are distributed by the NGO partners. SARC implements distributions through its branches and sub-branches, or through local charities in locations where it has no presence.

The number of WFP staff in country has gradually increased to over 200; the majority of these are national staff. WFP and local partners are currently implementing three main schemes - general food distribution, BSFPs for young children and ready-to-eat rations. The latter are distributed to newly displaced families with limited access to food or cooking facilities during the initial days of their displacement. In late 2014, two additional components were added: a school feeding programme to encourage regular attendance in school and distribution of food vouchers to promote dietary diversity for pregnant and breastfeeding mothers.

Needs assessment in November 2013

A WFP/FAO Joint Rapid Food Needs Assessment was conducted in November 2013 in Syria, in collaboration with the Ministry of Agriculture and Agrarian Reform and the Ministry of Social Affairs. It indicated that some 9.9 million people were estimated to be vulnerable to food insecurity and unable to purchase sufficient food to meet basic needs. Of these, some 6.3 million were estimated to be particularly exposed to the effects of conflict and displacement and in critical need of sustained food assistance. A severe reduction in agricultural production, combined with constraints in marketing available produce, as well as weakened import capacity to meet domestic demands, have increasingly limited food availability over time. Compounding the devastating effects of the conflict, exceptionally low levels of rainfall during the 2013/2014 winter season conditions impacted food production in 2014 and further exacerbated Syria’s humanitarian crisis. Furthermore, inflation, high commodity prices and growing rates of unemployment significantly reduced household purchasing power. Foods and fuels have been severely hit by price inflation particularly in northern governorates. On the other hand, prices have actually dropped in some southern governorate areas. As available resources have been depleted over time and resilience weakened, households have increasingly resorted to negative coping strategies including a reduction in both the quantity and quality of food consumed, a decrease in dietary variety, withdrawing children from school and selling assets.

General food distribution (GFD)

General food distribution (GFD)

Targeting

WFP’s GFD targets the most vulnerable households across all 14 governorates. WFP establish the target for each governorate on the basis of available needs assessment as well as consultation with partners (see Box 1). The assistance prioritises displaced households who have lost their main source of income, as well as poor communities hosting a large number of displaced families. Each household receives a food basket sufficient to feed a family of five for one month. The monthly family food basket consists of a variety of commodities such as rice, bulgur wheat, pasta, pulses, vegetable oil, sugar and salt. In 2014, the food basket was revised from 1680 kcals to provide up to 1,920 kcal per person per day. This increase was effected as WFP’s programme monitoring findings suggested that families were increasingly less able to access additional food from alternative sources, mostly relying on the GFD. The quantity and composition of the basket has been subject to changes depending on commodity availability and pipeline status. Figure 1 presents the target and reached populations up to July 2014. In August 2014, food distributions reached over 4.1 million people, or 98% of the month’s target.

Box 1: WFP’s targeting approach

WFP establishes the ration type in consultation with partners, according to nutrition considerations, local preferences and procurement capacity. The ration is then approved by the relevant government authorities. Targeting criteria are also established in consultation with partners, based on the following vulnerability criteria:

- Persons and households that have been displaced and have little or no income for food

- People located in or near areas subject to armed activities with little or no income for food

- Persons and households hosting a displaced family with little or no income for food

- Poor people in urban and rural areas affected by the multiple effects of the current events and who have little or no income for food.

Challenges

Distributions are conducted on a monthly basis in order to balance meeting the immediate food needs of beneficiaries with logistical challenges associated with such wide-scale activity across insecure areas. In 2013, widespread insecurity restricted access to many areas of the country, preventing the distribution of assistance at the planned scale. Particularly in the north, escalating infighting among multiple armed groups closed access routes and deadlocked assistance to Al-Hasakeh for most of the year, to rural Aleppo from August 2013 and eastern Aleppo city from September 2013. By November, the entire north-east was cut off as routes to Ar-Raqqa and Deir-ez-Zor were also blocked by continuous clashes. Haphazard access narrowed the scope of monitoring activities which could not be conducted in Ar-Raqqa, Deir-ez-Zor and Quneitra for the entire year. Furthermore, shifting patterns of active conflict prevented WFP teams from visiting the same sites each month, obliging them to rotate distributions among locations as security conditions permitted. Access constraints continued into 2014 as the crisis became more protracted. WFP planned and ‘reached’ general food distribution beneficiaries are shown in Figure 1 (Jan – July 2014).

Distributions are conducted on a monthly basis in order to balance meeting the immediate food needs of beneficiaries with logistical challenges associated with such wide-scale activity across insecure areas. In 2013, widespread insecurity restricted access to many areas of the country, preventing the distribution of assistance at the planned scale. Particularly in the north, escalating infighting among multiple armed groups closed access routes and deadlocked assistance to Al-Hasakeh for most of the year, to rural Aleppo from August 2013 and eastern Aleppo city from September 2013. By November, the entire north-east was cut off as routes to Ar-Raqqa and Deir-ez-Zor were also blocked by continuous clashes. Haphazard access narrowed the scope of monitoring activities which could not be conducted in Ar-Raqqa, Deir-ez-Zor and Quneitra for the entire year. Furthermore, shifting patterns of active conflict prevented WFP teams from visiting the same sites each month, obliging them to rotate distributions among locations as security conditions permitted. Access constraints continued into 2014 as the crisis became more protracted. WFP planned and ‘reached’ general food distribution beneficiaries are shown in Figure 1 (Jan – July 2014).

Food assistance to millions of civilians trapped in besieged locations, including an estimated 800,000 in Rural Damascus, remained sporadic despite unrelenting appeals for unhindered access. Al-Hasakeh is one of the hardest governorates to reach with humanitarian assistance. The continued closure of border crossings, active fighting in neighbouring governorates and radical armed groups blocking passage of trucks severely disrupted overland food deliveries since July 2013. As needs in the governorate continued to grow and food security of affected populations deteriorated, on three instances WFP was compelled to resort to costly but necessary emergency airlifts as the only means to deliver food to the targeted 227,170 civilians. The first airlifts were conducted in December 2013 when 6,025 food rations for 30,000 people were airlifted from Erbil to cover just 13% of the monthly requirements. Through the second round of airlifts, conducted between February and March 2014, WFP was able to deliver just over 16,000 rations out of a planned 32,500 to support 80,000 people in the governorate. These were suspended in mid-March after Turkish authorities granted the long awaited greenlight for the passage of 10,000 food rations into Al-Hasakeh through Nusaybeen on the Syria-Turkey border. However from April 2014, the governorate was once again cut-off from access. As a result, in July 2014, a third round of airlifts was implemented from Damascus. A total of 10,000 family food rations for 50,000 people and 3,000 ready-to-eat rations to support the immediate needs of newly displaced families were delivered. During January 2014, 17,500 people were assisted with 3,500 ready-to-eat rations in Homs and Rural Damascus.

Each monthly cycle is typically completed over the course of 45 days, due to access constraints and extended dispatch cycles. WFP has continuously had to make adjustments to the ration due to funding and supply chain issues. This has resulted in reductions in ration size. There have been many constraints to providing a full ration including delays in procurement, inspection and quality issues that delay approval in country and insufficient pledges from donors. To date (September 2014), cash flow problems have been mitigated by the use of WFP’s internal advance funding mechanism, which have allowed borrowing against future contributions. However inadequate funding commitments have become a severe constraint (see later).

In April 2013, WFP added wheat flour to the food basket in response to widespread wheat flour and bread shortages. Targeting 70% of WFP’s planned beneficiaries, the flour is provided to households living in areas where the effects of the conflict have decreased availability and reduced milling and bakery capacities, to the extent that target beneficiaries are reliant upon WFP wheat flour distributions to meet their bread needs. For the beneficiaries that receive fortified wheat flour, the food basket provides approximately 80% of daily caloric requirements. The food basket satisfies approximately 52% of minimum daily caloric needs for those residing in areas not targeted by wheat flour distributions, In areas where home baking is common, wheat flour is distributed directly to beneficiaries, while in other locations, wheat flour is supplied to functioning bakeries through SARC and other partners. Governorates that do not receive wheat flour include Damascus, Tartous and Lattakia due to availability of bakeries. Governorates that receive 100% of wheat flour include Rural Damascus, Hama, Idleb,Ar-Raqqa, Al-Hassakeh, Deir ez-Zor and Dar’a. All remaining recipient governorates receive 70% of wheat flour. Those that do not receive flour do not get any additional items.

Monitoring

Monitoring

WFP have common monitoring tools and platforms in the region, as well as dedicated monitoring staff, although monitoring has been weak in Syria (only 15% coverage for 2013) due to insecurity and access constraints. However, by January 2014, WFP was able to augment its monitoring capacity by engaging third-party monitors who are able to access locations WFP staff cannot. This has led to an improvement of the monitoring coverage to 41% of distribution locations. WFP monitors all accessible distributions by examining the process of beneficiary verification and the performance of cooperating partners. Beneficiary satisfaction with the distribution procedures is also monitored. Both female and male beneficiaries are consulted in the process. Shop monitoring examines the redemption of vouchers, type of commodities purchased, prices charged as well as beneficiary and shopkeeper satisfaction with the overall process. Beneficiary monitoring examines household outcome indicators including food consumption scores, dietary diversity and the various coping mechanisms used.

Monitoring data allowed comparison of beneficiary and non-beneficiary households and findings indicated poorer dietary diversity of the latter – especially with regard to access to fruits, vegetables, meat and dairy products.

Prevention of acute malnutrition

In March 2013, a BSFP was initiated to provide nutrition support to young children, prioritising 240,000 children aged 6-59 months. In 2014, over 189,000 children at risk of malnutrition were provided with nutrition support, including those in hard-to reach areas in Hama and Rural Damascus for the first time in months. Two programme variations (using different products) have been employed in different governorates. Implemented in partnership with the Ministry of Health and UNICEF, one scheme provides monthly rations of Plumpy’Doz® (a nutritional supplement for children) to children aged 6-59 months living in internally displaced persons (IDP) collective shelters. Since September 2013, three NGOs in partnership with WFP extended the feeding programme beyond official IDP collective shelters to reach vulnerable children residing in host communities in Tartous, Homs and Hama. Under the second BSFP variant, the supplementary product Nutributter® for the prevention of micronutrient deficiencies is being distributed to children aged 6-23 months living in collective shelters and among host communities in the northern governorates of Syria.

Fuel distribution

In response to anticipated harsh winter conditions during 2013/14, WFP provided emergency fuel support to vulnerable families with limited access living in collective IDP shelters, in partnership with UNHCR. A total of 58 collective shelters in Homs, Hama and Damascus were supplied with 100,000 litres of fuel to cover heating requirements for four months while 10,000 heat-retention Wonder-bags® were distributed to families unable to cook WFP food rations. A total of 2,500 Wonder-Bags® (out of 4,100 dispatched), were distributed to families in rural Damascus, Damascus and Idleb while over 24,000 litres of fuel were supplied to the 58 targeted collective shelters.

Voucher scheme targeting pregnant and lactating (PLW) women

The October 2013 Humanitarian Needs Overview (HNO) estimated that 300,000 PLWs across the country were at risk of micronutrient deficiencies and required nutrition support, as well as improved awareness of appropriate feeding practices. In addition, WFP’s monitoring findings illustrated that access to and consumption of fresh produce (such as fruits, vegetables and animal protein) by families, including PLW, was very limited, increasing their vulnerability. Hence, WFP introduced a targeted voucher-based nutrition programme to complement the GFD ration and improve dietary diversity for pregnant and lactating women. Lauched in July 2014, the pilot is targeting initially 3,000 women in Homs and Lattakia cities. Beneficiaries receive vouchers to the value of US$23 to purchase fresh products, including vegetables, fruit, meat and dairy products, which are not part of the general food ration. It is planned to target up to 15,000 women as this programme is fully rolled out.

School feeding

School feeding

An estimated 2.3 million children in Syria are no longer regularly attending school or have dropped out completely. As part of the UNICEF-led ‘Lost Generation’ strategy to improve access to learning and facilitate a return to normalcy, in 2014, WFP introduced a school feeding programme targeting some 350,000 children in four critically affected governorates, including Rural Damascus, Homs, Tartous and Aleppo. The first phase of the project was launched in July 2014, targeting schools in critical districts in Rural Damascus and Tartous. During the first phase, up to 100,000 elementary school children aged 6-12 years received daily rations of fortified date bars, conditional on attendance. The programme, which was initially implemented in summer schools, has been transferred to regular schools when classes resumed in September.

Inter-UN coordination

Inter-UN coordination

WFP has had a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with UNICEF in Syria, since January 2013, whereby both agencies have committed, through joint programming, to scale up nutrition interventions to address malnutrition, as well as to tackle micronutrient deficiencies and promote the population’s nutrition status. Accordingly, WFP currently focuses on the prevention of acute malnutrition (using Plumpy’Doz), while UNICEF focuses on its treatment (using Plumpy’Sup and Plumpy’nut). In addition, both agencies collectively focus on the prevention of micronutrient deficiencies (using Nutributter and micronutrient powder). A key challenge for both organisations has been the lack of current nutrition data to guide programming, due to access constraints to certain areas. WFP’s programme for PLW complements the support already provided by UNICEF, WHO and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), in the form of micronutrient supplementation and reproductive health services. Through the Nutrition Sector Working Group, led by UNICEF, nutrition assessments are conducted to update the nutrition situation as well as define nutrition strategies.

Logistics

Logistical needs inside Syria are continuously changing due to the fluidity of the security and access situation on the ground, and require a high degree of flexibility in planning. In this context, a complex chain of delivery underpins the implementation of these programmes.

WFP imports food into Syria through the primary supply corridors of Beirut and Tartous, while the use of Lattakia port was also increased during 2013. In addition, a fourth corridor through Jordan has been activated in July 2014 following the adoption of UN Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 21652. WFP retains the capability to rapidly adjust its use of available corridors in response to changes in the operating environment. Accordingly, the expansion of additional corridors through Turkey is also under use, thanks to UNSCR 2165.

Upon arrival in Syria, food commodities are assembled in five storage and packaging facilities strategically located in Safita, Lattakia, Homs and Rural Damascus. To avoid assembling the food basket on-site under challenging security conditions, food is packaged prior to dispatch, thus mitigating the risks of losses and ensuring that each family receives the adequate food items. Each packaging facility produces up to 10,000 food rations every day, which are then dispatched by over 1,000 trucks each month to governorates allocated to each centre according to respective strategic advantages. Facilities in Safita, Lattakia and Homs offering a good staging point to cover the requirements of central and northern governorates, while facilities in Damascus serve the southern governorates. This allocation maximises the efficiency of food dispatches while reducing travel times, thus mitigating exposure of cargo to security threats.

Once packaged, the family food rations are dispatched to secondary storage points inside Syria and delivered to WFP partners on the basis of monthly allocation plans. In some cases, WFP purchases pre-packed rations which are transported by suppliers directly at the handover

points to partners inside Syria, without being processed through WFP facilities. Wheat flour milling is undertaken outside of the country, in Mersin and Beirut. Subsequently, bagged wheat flour is shipped respectively to Syrian ports or trucked to Damascus. For transport inside Syria, WFP utilises existing commercial transport settings, encouraging local capacities where possible. Previously working with one single transport partner, WFP contracted five additional transport companies in September 2013 to increase its delivery capacity and respond to the growing need for humanitarian assistance within the country. Each transporter is allocated specific areas on the basis of a previously established presence in certain parts of the country. This maximizes WFP’s ability to deliver to all locations. For specific areas where surface access can be sporadic and the humanitarian situation particularly dire, contingencies for airlift of life-saving supplies are arranged.

Food distributions take place at final distribution points (FDPs) agreed upon with partners. Due to the instability of security conditions on the ground, the number of FDPs and their locations vary from month to month, as partners may no longer be able to perform distributions in previously accessible locations, or beneficiaries may be unable to reach planned distribution sites.

Activation of the Logistics Cluster

Activation of the Logistics Cluster

Following the recommendation of the UN Regional Emergency Coordinator for the Syria Emergency, the Logistics Cluster was activated in January 2013 to support overall logistics coordination and provide services to humanitarian actors responding to the emergency in Syria. The Logistics Cluster, led by WFP, fills logistics gaps in emergencies on behalf of the humanitarian community, whilst also providing a platform for coordination and sharing of key logistics information among partners. As such, it provides free-to-user services to its humanitarian partners, including dedicated warehousing space for inter-agency cargo, as well as transport services throughout Syria. In addition, the Cluster ensures support for inter-agency convoys to deliver assistance to the most vulnerable communities in otherwise inaccessible parts of the country. The Logistics Cluster offers also humanitarian flights to Qamishli, on a cost-sharing basis.

Furthermore, the Logistics Cluster has established a logistics coordination forum in Damascus, Beirut and Amman. Over 30 organisations (UN agencies, NGOs, INGOs, and donor agencies) regularly attend meetings where participants discuss logistics bottlenecks and develop common solutions for improved humanitarian response. In addition, the Cluster produces regular logistics information products including situation reports, maps, assessments, meeting minutes, snapshots and flash updates on the Syria Logistics Cluster webpage, and shares them via a Cluster mailing list. As of June 2014, a total of 17 organisations were benefiting from the Logistics Cluster services for their operations inside Syria. As additional organisations are allowed to work in Syria, the number of service requests has been increasing. Accordingly the Cluster has been rapidly scaling up its operations, and continues to be ready to expand further if required.

In 2014, WFP logistics in close coordination with procurement and shipping units, updated the Concept of Operations for the Syria Operation’s Supply Chain and put in place measures to mitigate pipeline breaks and ensure timely arrival of commodities in Syria. Arrangements with suppliers now ensure a readily available stock of food commodities for immediate purchase upon receipt of funds by WFP. Additionally, procurement will be conducted solely within the Mediterranean, significantly accelerating lead times for the arrival of food in the country.

Risks to staff safety continue to represent the greatest threat to sustaining WFP operations in the country. Should the security environment deteriorate further, WFP may be forced to reduce its footprint inside the country by deploying both national and international staff to work from alternative locations. Remote management plans have been developed, including the increasing use of WFP’s Lebanon and Jordan offices if necessary.

Ongoing challenges and lessons learnt

Ongoing challenges and lessons learnt

WFP’s ability to deliver and distribute adequate food is affected by access restrictions and shrinking humanitarian space. However, WFP continues to work with the UN Country Team and partners to maintain a presence on the ground, implement activities and continuously advocate for unhindered humanitarian access.

WFP, and hopefully the Syrian population, have benefited from a clear WFP operational strategy at the outset. Recognising the political nature of the crisis and that high levels of insecurity were going to prevent WFP from operating as normal, the decision was taken early on to adopt a pragmatic and opportunistic approach. WFP began its Syria emergency operation in 2011 and was the first organisation to launch an emergency operation without the full approval of the Syrian government, gradually building on its programming base to expand the humanitarian space through engagement and negotiation. This has been a slow process requiring persistence. Although at first and for many months it was only possible to work through SARC, WFP were gradually allowed to engage with more local NGOs and were not shut down as a result. WFP did not control the modus operandi but found that they could expand humanitarian space in a way that was acceptable and met needs of millions of people, including other organisations working on behalf of the conflict affected population. WFP has worked through numerous local partners since they have better access to most of the governorates. This has been a very positive development and has effectively changed the landscape of civil society in Syria by investing in building up capacity of national agencies.

While working in Syria, WFP have had to tread carefully with regard to the cross-border programme from southern Turkey as this expanded with an increasing number of agencies basing themselves in Gaziantep and Antakya in southern Turkey. With mounting criticism of the UN’s lack of engagement in the cross-border programme, WFP began engaging with INGOs involved in cross-border work in early 2013 and sent a number of staff to liaise with the NGOS and ACU in order to focus on information management and nurture mutual understanding. This was followed by the deployment of a Global Food Security Cluster lead to work with NGOs doing cross-border work and to improve collaboration. This was a slow consensus and trust building exercise leading to the establishment of systems for sharing information about programming from southern Turkey and Damascus.

In May 2014, additional measures to improve operational coordination and joint planning were taken. This involved constructing a joint forward looking plan that indicated where there were operational overlaps and engaging in discussions with partners about how to decide on ‘who does what, where’. Another meeting was held in July 2014 where an action plan was agreed for cross-border programming from Turkey, Jordan and programming from Damascus, looking at the whole of Syria. A key challenge for all stakeholders is how to determine numbers in need.

Adoption of UNSCR 2165 on 14th July has had a positive impact in enabling WFP use the most direct route to reach cut-off communities. All WFP programming, including cross-border and cross-line, is now managed from Damascus. There are no WFP cross-border operations managed from Turkey or Jordan. This position has been taken in order not to undermine the mandate under UNSCR 2165. This has made programming harder in one sense as there are complex discussions and negotiations with the Syrian Government but WFP is gradually overcoming challenges related to fragmented and uncoordinated responses. While information about INGO programming is treated confidentially, any WFP cross-border programming from Turkey is planned from Damascus and the government is informed accordingly through the office of the Humanitarian Coordinator. An unexpected consequence of the UNSCR 2165 has been an increased readiness of the Government of Syria to facilitate cross-line convoys, a welcome development for WFP. This may partly reflect the battle for hearts and minds as the threat of ISIS appears to have increased.

Adoption of UNSCR 2165 on 14th July has had a positive impact in enabling WFP use the most direct route to reach cut-off communities. All WFP programming, including cross-border and cross-line, is now managed from Damascus. There are no WFP cross-border operations managed from Turkey or Jordan. This position has been taken in order not to undermine the mandate under UNSCR 2165. This has made programming harder in one sense as there are complex discussions and negotiations with the Syrian Government but WFP is gradually overcoming challenges related to fragmented and uncoordinated responses. While information about INGO programming is treated confidentially, any WFP cross-border programming from Turkey is planned from Damascus and the government is informed accordingly through the office of the Humanitarian Coordinator. An unexpected consequence of the UNSCR 2165 has been an increased readiness of the Government of Syria to facilitate cross-line convoys, a welcome development for WFP. This may partly reflect the battle for hearts and minds as the threat of ISIS appears to have increased.

Against the backdrop of these positive humanitarian and political ‘sea-changes’ is a looming resource crisis affecting WFP, who will effectively be running out of money for this and other programmes in the region in late 2014, resulting in dramatic scaling back of programming3. This could not be happening at a worse time as winter approaches. The irony is that in August 2014, WFP managed to reach almost 4.1 million Syrians in Syria, the highest number since the emergency response began in 2011. In October, WFP hopes to still reach 4.25 million Syrians in country but will provide a food basket with a 40% reduction of the planned caloric requirement. WFP will do everything it can to advocate and strengthen resource mobilisation efforts in order to avoid a reduction of WFP assistance.

For more information, contact: Rasmus Egendal, email: rasmus.egendal@wfp.org +962 7989 47301 or Adeyinka Badejo, email: adeyinka.badejo@wfp.org

1 https://www.unglobalcompact.org

2 http://unscr.com/en/resolutions/2165

3 http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2014/sep/18/world-food-programme-cut-aid-syria