WHO response to malnutrition in Syria: a focus on surveillance, case detection and clinical management

By Hala Khudari, Mahmoud Bozo and Elizabeth Hoff

Hala Khudari, WHO Technical Officer at WHO Syria, joined WHO in 2011 and is a BSc (Nutrition and Dietetics) and MSc in Nutrition graduate from the American University of Beirut. For the last 3 years she has helped develop the WHO nutrition response programme in Syria.

Hala Khudari, WHO Technical Officer at WHO Syria, joined WHO in 2011 and is a BSc (Nutrition and Dietetics) and MSc in Nutrition graduate from the American University of Beirut. For the last 3 years she has helped develop the WHO nutrition response programme in Syria.

Mahoud Bozo is a nutrition expert/paediatrician and a WHO consultant since Nov 2013. He has widespread experience in research in paediatric gastroenterology and nutrition and was former general coordinator of paediatrics in MOH Syria (2005-2012).

Elizabeth Hoff was appointed WHO representative in Syria in April 2014 (acting representative July 2012 – April 2014). She has more than two decades experience in Africa, the Middle East, Asia and Eastern Europe and previously was coordinator for resource mobilisation and external relations under the Emergency Risk Management and Humanitarian Response department in WHO HQ, Geneva.

We wish to express our sincere appreciation for the support and input from WHO’s information management team and field staff for their feedback, commitment and responsiveness to build up the information provided. Special thanks go to Dr. Ayoub Al-Jawaldeh, Nutrition Regional Advisor, for his invaluable technical support and guidance, in addition to the publication office at the Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office.

We wish to express our sincere appreciation for the support and input from WHO’s information management team and field staff for their feedback, commitment and responsiveness to build up the information provided. Special thanks go to Dr. Ayoub Al-Jawaldeh, Nutrition Regional Advisor, for his invaluable technical support and guidance, in addition to the publication office at the Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office.

Three years into a brutal crisis, the protracted conflict in Syria has had an immensely negative impact on essential living conditions of the Syrian population. Access to basic services and commodities such as food, livelihoods, safe drinking water, sanitation, education, shelter and health care has been compromised. This in turn has increased the populations’ vulnerability to poverty, violence, food and nutrition insecurity, and disease. The volatile nature of the crisis has created unpredictable and unstable living conditions for the population. The ongoing conflict has caused forced displacement, socioeconomic limitations, insecurity and a lack of access to basic services. Coupled with recurrent droughts, the conflict has significantly affected food security and livelihoods and thus, has adversely impacted nutritional status, especially in children under 5 years; an already vulnerable population. More specifically, chronic poor dietary diversity, inadequate/improper infant, young child and maternal feeding practices, as well as geographical and gender inequalities have heightened the risk of malnutrition in children under five years.

According to the Syrian Family Health Survey (2009), conducted prior to the crisis, the nutritional situation of children under five years of age was poor, with an estimated 23% of them being stunted, 9.3% wasted and 10.3% underweight. Exclusive breastfeeding rates stood at 42.6% while the proportion of newborns introduced to breastfeeding within the first hour was 42.2%1. Micronutrient deficiencies were also recorded in pre-crisis Syria in 2011, presenting a risk for sub-optimal growth among children; for example, anaemia prevalence among 0-59 month old children was 29.2%2, while there was an 8.7% Vitamin A deficiency rate3 and 12.9% iodine deficiency prevalence4. Neonatal mortality rates, infant mortality rates and under-five mortality rates stood at 12.9/1000, 17.9/1000 and 1.4/1000 respectively5.

According to the Syrian Family Health Survey (2009), conducted prior to the crisis, the nutritional situation of children under five years of age was poor, with an estimated 23% of them being stunted, 9.3% wasted and 10.3% underweight. Exclusive breastfeeding rates stood at 42.6% while the proportion of newborns introduced to breastfeeding within the first hour was 42.2%1. Micronutrient deficiencies were also recorded in pre-crisis Syria in 2011, presenting a risk for sub-optimal growth among children; for example, anaemia prevalence among 0-59 month old children was 29.2%2, while there was an 8.7% Vitamin A deficiency rate3 and 12.9% iodine deficiency prevalence4. Neonatal mortality rates, infant mortality rates and under-five mortality rates stood at 12.9/1000, 17.9/1000 and 1.4/1000 respectively5.

Coordinating response

The confluence of factors and lack of solid data on the nutritional status alerted the humanitarian community to the possibility that cases of malnutrition in Syria were going undetected. This prompted international organisations and national counterparts to address the prevention, detection and treatment of emerging malnutrition cases. With the establishment of the Nutrition Sector Working Group headed by UNICEF and the Ministry of Health (MOH) in the second quarter of 2013, which emerged as a result of expanded nutrition activities and increased nutrition partners in the field, the response to malnutrition has gradually been strengthened. This has been realised through the involvement of key UN agencies including the World Health Organisation (WHO), UNICEF and the World Food Programme (WFP) and key national authorities and implementing partners including the MOH, Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE), as well as international and national non-governmental organisations (NGOs) such as International Medical Corps, Action Against Hunger (ACF) and the Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC). These stakeholders have scaled up their response by adopting a holistic strategic approach that covers i) preventative micronutrient supplementation; ii) screening for and referral of malnutrition cases; and iii) outpatient and inpatient treatment of acute malnutrition. WHO’s response has focused on strengthening screening of children under five years for malnutrition and hospitalised care of complicated cases of severe acute malnutrition (SAM).

Scaling up WHO nutrition activities

Scaling up WHO nutrition activities

Revitalising the Nutrition Surveillance System

Prior to the conflict, in 2009, a national nutrition surveillance system was established to report on acute and chronic malnutrition of children under 5 years visiting health facilities for their routine immunisation. The system extended to providing parents with information and a service to monitor child growth. However, with the conflict driven damage to the health system and the consequential shortage in nutrition personnel, the national nutrition surveillance system has suffered from a reduction in the quality of nutrition service provision and deterioration in reporting and monitoring. With an expected increased number of acute malnutrition cases, and a scarcity of nutrition services, there was a concern that malnutrition cases were going undetected.

In order to understand the impact on overall nutrition related morbidity and mortality, detection and reporting on cases would need to be improved. In order to enhance the detection of malnourished children and fill the information gap, WHO is collaborating with the MOH and other partners to improve and strengthen the Nutrition Surveillance System. Between April and July 2014, twelve health centres from 12 governorates were selected to pilot a modified surveillance system. This modification encompassed revised reporting and monitoring tools and providing trained human resources. The pilot governorates were selected using two criteria: (i) conflict-impacted areas (Daraa, Homs, Aleppo, Rural Damascus, Idlib, Quneitera and Deir-ez-zor) and (ii) densely populated areas with high numbers of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) (Damascus, Tartous, Latakia, Hama and Sweida). Coverage rates of nutrition surveillance, capacity of human resources, availability of physical space, and equipment needs were also assessed and evaluated within the pilot timeframe. Aside from the pilot centres, nutrition surveillance was also started up again in the highly conflict-affected governorate of Ar-Raqqa, through the coordinated efforts of WHO field staff.

Numerous constraints were reported by the pilot nutrition surveillance centres. The lack of human resources, space, equipment and telecommunication-reporting utilities were cited as challenges by a number of Governorates. These obstacles were especially evident in the case of Deir-ez-Zor, with a significantly under-staffed health centre, where the single health provider present was only able to take mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) measurements of 300 U5 children per month.

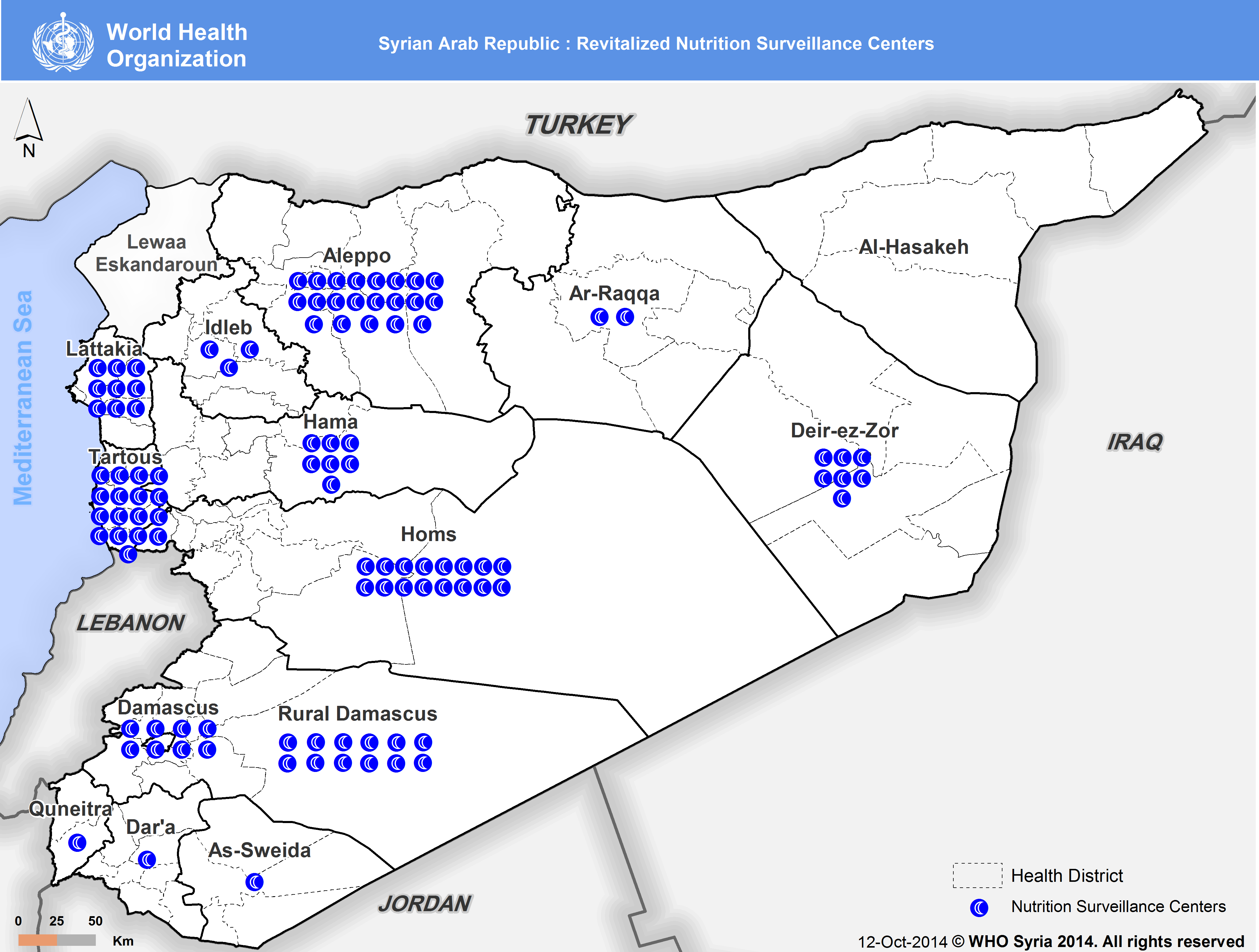

One aim of the pilot was to test the effectiveness of the capacity building trainings conducted on anthropometric measurement techniques including weight, height and MUAC and the reporting system. This included assessment of the tools and flow of data and adequacy of referrals and standardised management following community based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) and WHO 2013 protocols. The findings of the pilot have demonstrated what changes need to be effected for the next phase of the nutrition surveillance strengthening which aims to expand to 10 health centres within each governorate including enhancing capacity, provision of supplies and equipment and reporting templates and tools. The expansion began in mid-July when a team of health workers from 20 centres in Damascus and Rural Damascus were trained. By mid-October, 105 surveillance centres were following the improved surveillance system (see Map 1).

Map 1: Revitalised Nutrition Surveillance Centres

By the end of 2014, it is anticipated that more than 115 health centres will be integrated into national surveillance system. In 2015, a number of NGOs will be integrated into the programme in order to reach more children in affected and hard-to reach areas. The regular and accurate flow of information through monthly paper-based published reports shared with WHO and centrally with the MOH by main nutrition offices at the directorates of health in the governorates. Reports include cases of malnutrition in children under five years across the country that will be analysed and utilized to monitor prevalence and trends, and more importantly early detection of cases and referral for treatment.

A step towards success: Active surveillance in Aleppo Governorate

The surveillance system in the northern Governorate of Aleppo has set a high standard and many ways been exemplary. As one of the main the population centres in Syria, Aleppo city was once considered the industrial heart of the country. It is surrounded by large rural areas that have been severely affected by violent conflict for over 2 years. Huge population displacement, food shortages and economic losses are some of the many hardships Aleppo Governorate inhabitants have faced, making families and especially their children more susceptible to malnutrition. With a very active surveillance team, screening for malnutrition was optimised not only through screening cases entering facilities but also via mobile teams visiting shelters for the internally displaced in the city and conducting referrals for cases in need of treatment.

Since the start of 2014, the surveillance in Aleppo has consistently reported on cases from four health centres in four health districts in the governorate of Aleppo (the numbers available so far are limited to specific locations in the governorate, are not statistically representative and therefore not included here). In the month of August, 12 facilities have been activated in urban and rural areas of Aleppo. These facilities are expected to screen an approximate 4000 children per month. In locations experiencing intermittent violence like north Aleppo, due to the security situation, some health centres stop reporting when the security situation is dire. This varies the total number of centres reporting from month to another with a typical difference of 1-2 centres.

Referral of detected cases and hospital care of complicated cases of severe acute malnutrition (SAM)

The implementation of the pilot phase of the modified Nutrition Surveillance System led to an increase in the detection of cases of malnutrition requiring treatment and confirmed morbidity and mortality due to nutrition related disease. Data collection and analysis on SAM is still ongoing; the full report will be out by early 2015. This increase highlighted the importance of establishing a solid referral system for specialised treatment to reduce associated mortality and morbidity.

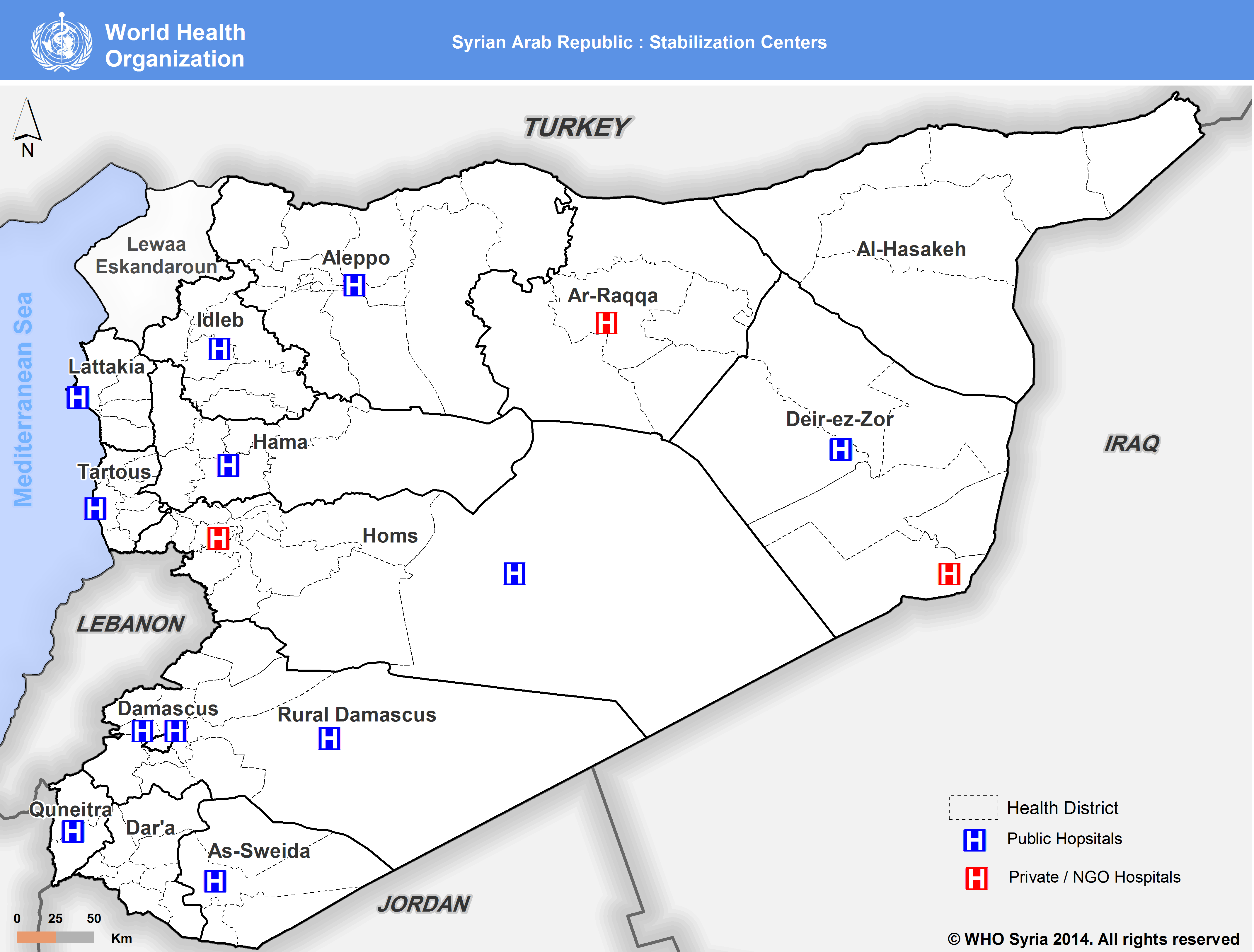

Since January 2014, WHO has supported the establishment of Stabilisation Centres (SC) for the management of SAM in hospitals across the country in line with WHO’s SAM Management Protocol, updated in 2009 and 2013. So as to not create parallel systems within hospitals, these centres have been integrated within paediatric departments at the main public hospitals. Support to these SCs has been extended in three main areas, (i) building the capacity of the health workforce, critical for effective SAM management and treatment (ii) filling gaps in medicines, medical supplies and equipment for treatment of complicated SAM, e.g. anthropometric equipment, antibiotics, minerals, vitamins and F100, F75 formulas and (iii) providing technical support for treatment protocols and reporting. To date, over 350 health professionals from MOH, MOHE and private hospitals in Damascus, Rural Damascus, Homs (including Homs city and Tadmor), Hama, Aleppo, Idlib, Lattakia, Deir-ez-zor, and Quneitera have been trained on the WHO SAM Management Protocol adopting best practice techniques and food safety measures6. Additionally, systemised reporting through a developed hospital reporting template, has been initiated in collaboration with MOH.

As of August 2014, SCs in hospitals were established in nine governorates with MOH and local NGOs. Centres within the public hospitals are available in Damascus (2), Aleppo (1), Hama (1), Lattakia (1), Qutaifeh in Rural Damascus (1), Homs (1-Tadmor), Quneitera (1), Sweida (1), Deir-ez-Zor and Idlib (1) (see Map 2). Eight of these centres have received SAM cases in Damascus, Aleppo, Lattakia, Idlib, Deir-ez-Zor, Sweida and Hama. In cities where public health facilities have been significantly damaged such as Homs, Deir-ez-Zor (Boukamal), Dara’a and Ar-Raqqa, cases are referred to private or NGO hospitals.

Map 2: Functional Stabilisation Centres in Syria

Reports from Damascus, Homs, Dara’a, Aleppo, Latakia, Hama and Deir-ez-Zor have been received on complicated cases of SAM requiring urgent medical attention. In the case of Hama, over a period of three months (April-July), 42 cases of complicated SAM were admitted in comparison to six cases admitted between January and March before the establishment of the SC. Further expansion of SCs to all governorates is planned with the aim to situate at least one centre per governorate to manage the caseload of SAM cases requiring hospitalised care. Future centres will be located in hospitals in Deir-ez-Zor (Deir-ez-Zor city), Dara’a, Tartous, Sweida, Qamishli, and Hassakeh.

Mainstreaming Infant and Young children feeding promotion

Mainstreaming Infant and Young children feeding promotion

Infant and young child feeding (IYCF) and breastfeeding promotion has been prioritized and mainstreamed within most nutrition support activities. In Syria before the crisis, the rate of six-month exclusive breastfeeding had been consistently low (approximately 43%). Without the proper support of health staff and community based initiatives, lactating mothers have been struggling during the crisis with initiating breastfeeding. In many cases, due to displacement and overcrowded living conditions compounded by conflict-related distress, mothers lose confidence in the quantity and quality of their breastmilk, stopping breastfeeding all together and resorting to other practices. During an observational mission in early 2013, doctors and midwives reported an increasing number of women who wished to breastfeed their infants, mainly because they could not afford infant formula. Due to the short stay in health facilities following delivery, help with initiation of breastfeeding had been insufficient. Also during 2013, WHO received numerous requests from NGOs supporting populations in need including the displaced to provide breast-milk substitutes like infant formula. These requests were not supported as they counteract WHO/UNICEF global guidance to promote exclusive breastfeeding; instead, WHO focused on promoting optimal IYCF practices. Requests for infant formula over 2014 significantly decreased.

A capacity building and programme-strengthening project was identified as an essential element to promote breastfeeding at the health facility and community level with the aim of raising awareness among lactating mothers in both displacement shelters and host communities. Since early 2014, WHO has conducted five trainings for more than 190 doctors and health workers from Aleppo, Damascus, Rural Damascus, Quneitera, Sweida, Homs, Derezzor, Hama, Latakia, Hassakeh, Tartous and Daraa in cooperation with the MOH-primary health care department. Trainings covered the importance of breastmilk, its constituents, techniques on initiation of breastfeeding and its benefits for both child and mothers.

Breastfeeding promotion has been streamlined across all WHO nutrition activities. It has been included in all training courses conducted on nutrition surveillance allowing surveillance health workers to conduct breastfeeding consultations for concerned visiting mothers. Data collection on breastfeeding rates will also be included through the nutrition surveillance system in the upcoming months, providing information for analysis of trends and further investigations on causal factors of the changes to breastfeeding rates. As yet, no assessment has been conducted to investigate any links between breastfeeding status and acute malnutrition.

Preventative micronutrient supplementation

Equally important to strengthening treatment capacity, preventative measures against micronutrient deficiencies have also been scaled up by nutrition working group partners through blanket distribution of ready-to-use supplementary foods (RUSF). WHO has also contributed to this initiative through the distribution of micronutrients for children and mothers during immunisation campaigns and in health facilities. In 2014, up to 900,000 children and 7500 adults were provided with micronutrient supplementation.

The way forward

During the second half of 2014, WHO will be further enhancing its nutrition activities across four main areas:

1) Further strengthening of the nutrition surveillance system will be achieved through conducting decentralised trainings on nutrition surveillance to expand the re-activation of nutrition surveillance in 10 health centres in Latakia, Tartous, Idleb, Hama, Dara’a and Homs. Efforts will also be made to improve data entry, collection and reporting through strengthened operational capacity and procedures at the nutrition surveillance centres.

2) Distribution of supplies to SCs to improve and enhance treatment of admitted SAM cases. In order to expand geographical coverage, WHO is drawing on NGO and private sector capacities across the country. NGOs operating hospitals will be trained and supported with in-kind donations to also be able to treat detected complicated SAM cases.

3) Mainstreamed IYCF activities through extensive trainings for health workers in the health centres providing nutrition surveillance, allowing them to deliver key messages to mothers on the importance of breastfeeding and complementary feeding. Furthermore, two courses of training of trainers will be implemented to decentralise IYCF trainings across the country, contributing to raising the awareness of mothers visiting health centres or hospitals, or residing in displacement shelters or the host community.

4) Strengthened coordination with the Nutrition Working Group partners will be crucial in enhancing a coordinated referral process from surveillance centres, outpatient and inpatient treatment centres. Nutrition sector partners including MOH and SARC predominantly supported by UNICEF have worked to establish Outpatient Therapeutic Programmes (OTPs) in health centres to include the follow up and management of both SAM and MAM (moderate acute malnutrition) cases. Additionally, preventative nutrition services and blanket supplementation has been supported by WFP. These efforts have been strongly coordinated and continue to be through regular Nutrition sector meetings and bilateral meetings with UN sister agencies to bridge programmes and fill in gaps working towards a holistic CMAM approach.

WHO in coordination with nutrition sector partners has scaled up its nutrition response to help alleviate nutrition insecurity from a health perspective, aiming to provide quality nutrition services at health facilities to prevent, detect and treat cases of malnutrition and related mortality and morbidity. Efforts continue to obtain a clearer picture of the prevalence of malnutrition across the country. Halting the increase of malnutrition prevalence during the protracted Syrian crisis is crucial for children’s health, well-being and physical and cognitive development.

For more information, contact: Hala Khudari, WHO Technical Officer - khudarih@who.int

1WHO/MOH, Syrian Family Health Survey, Syria, 2009.

2Ministry of Health, Nutrition surveillance system report, Syria, 2011.

3Ministry of Health, Vitamin A deficiency Study, MOH, 1998

4Ministry of Health, Study on Iodine deficiency prevalence in Syria, MOH, 2006.

5See footnote 1

6World Health Organisation, Training course on the management of severe malnutrition, WHO/NHD/02.4, 2009