Measuring coverage at the national level in Mali

By Sophie Woodhead, Jose Luis Alvarez Moran, Anne Leavens, Modibo Traore, Anna Horner, Saul Guerrero

By Sophie Woodhead, Jose Luis Alvarez Moran, Anne Leavens, Modibo Traore, Anna Horner, Saul Guerrero

Based within the ACF-UK Operations Team, Sophie Woodhead coordinates all activities and research projects under the Coverage Monitoring Network. She has supported a number of coverage trainings in West, East and Central Africa as well as in Asia.

Jose Luis Alvarez Moran is a Public Health Epidemiologist with a PhD in Humanitarian Medicine and International Health. He is currently Senior Technical Advisor for Action Against Hunger UK, but has also worked with Terre des hommes and local NGOs monitoring and evaluating nutrition programmes in Mali, Benin, Philippines, Haiti and Pakistan.

Anne Laevens is UNICEF CMAM (IMAM) specialist in Bamako. She holds a Master in Public Health in Developing Countries from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. She has 14 years of experience working in nutrition and health projects in emergency, post conflict and development

Modibo Traore is a Nutrition Specialist at WAHO/ECOWAS Nutrition Department in Bobo Dioulasso, Burkina Faso. He obtained his Ph.D in nutrition from Université Laval, Canada. He has a great amount of experience on nutrition research and health disease control, spanning 17 years.

Anna Horner is Nutrition Manager with UNICEF Mali in Bamako. She holds a Master in Public Health Nutrition from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. She has been working in public health nutrition since 2003.

Saul Guerrero is Director of Operations at Action Against Hunger (ACFUK). Prior to joining ACF, he worked for Valid International Ltd. in the research, development and roll-out of CTC/CMAM. He has worked in over 20 countries in Africa and Asia.

The authors would like to thank the Government of the Republic of Mali, who gave authorisation for the implementation of the coverage survey and showed keen interest in the assessment. The authors would also like to thank Melaku Begashaw, Trenton Dailey-Chwalibog and Beatriz Perez-Bernabe for their joint implementation of the assessment, from organisation to data analysis. Last but not least, the carers, community leaders and community based volunteers work are acknowledged in this article as they were the major respondents of the SLEAC study. Their participation and time is much appreciated.

Location: Mali

What we know: Indirect national estimates of coverage of SAM treatment programmes are usual; there are few large scale/national coverage surveys to provide direct estimates.

What this article adds: In 2014, UNICEF, the Mali Ministry of Health and the CMN collaborated to implement a national scale assessment (SLEAC) of SAM treatment cove

rage in Mali. The overall point coverage level was estimated at 22.3%; sub-national coverage was heterogeneous. Lack of malnutrition awareness and programme awareness were the reasons most frequently reported for not accessing services. Those who were aware of both but did not attend gave reasons of distance and lack of money. A national workshop identified strategies to increase access, learning mechanisms to share programming experiences and further qualitative research in low coverage areas. Engaging government throughout increased planning and preparation time but was essential to ensure committed follow up action.

Over the last two years, the demand for national coverage information for severe acute malnutrition (SAM) treatment services has increased dramatically. This demand has come from national governments, United Nations (UN) bodies, and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), who recognise the need to measure programme quality and the barriers to access. Many donors have also recognised the importance for services to gain a better understanding of their treatment coverage, and actively encourage their programmes to reflect upon this. Whilst indirect national estimates are often available, based on estimated malnutrition prevalence data and admission reports, there are few countries that have direct estimations available. National or large scale coverage estimates do exist, however Nigeria and Sudan are indeed the only examples. Whilst in Sudan, the Simple Spatial Sampling (S3M) Methodology was used, the Nigerian government and Bureau of Statistics carried out a Simplified LQAS1 Evaluation of Access and Coverage (SLEAC) in collaboration with Action Against Hunger and Valid International.

In 2014, UNICEF approached the Coverage Monitoring Network (CMN)2 for support in the implementation of a national scale assessment of SAM treatment coverage in Mali. Results showed coverage to be low at a national level, demonstrating the need for improved programming and scaling up of treatment provision. Moreover the exercise also provided clear recommendations that have since enabled UNICEF and the Ministry of Health (DNS)) to take decisive action to improve access to SAM services in the country.

Why did we do it?

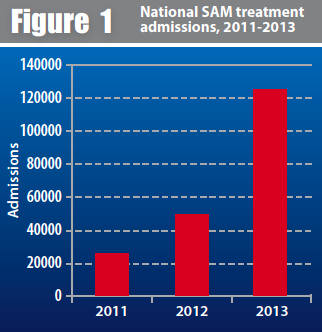

UNICEF has supported the Government of Mali to scale up access to SAM treatment, with all operational health centres in the country providing SAM treatment services by 2014. The number of SAM cases admitted and treated in the integrated management of acute malnutrition (IMAM) programme in Mali has increased steadily since 2011, with notable increases in 2013, which can be seen in Figure 1. Whilst services are increasingly available and clearly being utilised, levels of access must be evaluated against levels of need to understand why some areas may have high uptake and others low, as lessons can be learned from both scenarios. Where service uptake is low, it is particularly important to understand what barriers the population is facing so that measures can be taken to address those barriers, with lessons learned shared and disseminated to other areas.

Since the creation of the CMN, there has been increased interest in improving the accuracy of coverage data and this interest has grown to a desire for direct coverage estimates at the national level. Direct coverage estimates are able to demonstrate the proportion of children that treatment services are successfully reaching, as well as providing additional information on the barriers experienced in reaching the service. In 2014, the CMN partnered with UNICEF Mali in the implementation of a national coverage survey to help assess the performance of IMAM services in country and to inform future endeavours to ensure that treatment services are available to all3.

What did we do?

From April to June 2014, the CMN engaged with UNICEF to carry out a national coverage assessment. The survey was conducted across seven of nine regions in Mali, with the exception of the regions of Kidal and Gao, where the security conditions did not permit data collection at the time of the survey. The survey provided a detailed spatial representation of treatment coverage, with information at the ‘Cercle’ level, the administrative division into which regions are divided.

The SLEAC method was selected as the most appropriate survey method adapted to the national Malian context, as it is designed to estimate coverage over wide areas. SLEAC is intended for use in programmes delivering IMAM services over multiple or large services delivery areas, such as national or regional programmes delivering IMAM services in health districts through primary healthcare centres. The method classifies programme coverage for a service delivery unit, such as a health district. A SLEAC survey identifies the category of coverage (e.g. ‘low coverage’ or ‘high coverage’) that describes the coverage of the service delivery unit being assessed. The classification method is derived from a simplified LQAS classification technique that provides two-tier or three tier classifications. In this survey, a three-tier classification method was used in an effort to distinguish very high coverage service delivery units and very low coverage service delivery units from areas of moderate coverage.

The survey was implemented jointly by CMN, UNICEF and national counterparts, mainly the Division of Nutrition (DN) but also the Ministry of Health (DNS) and The National Institute of Statistics (INSTAT). Enough time was dedicated for planning, coordinating and communicating with the national counterparts in order to ensure capacity building and ownership. The results of the various stages of the planning were explained extensively and the participation of the national counterparts was sought in all stages of the planning, even if at times, making the process slower. The different stages of the joined planning involved the presentation of the SLEAC methodology to the national counterparts, the elaboration of a detailed budget, the elaboration and submission of a survey protocol to the ethical committee, the selection and training of data collectors, the supervision of field data collection and the collation and analysis of data. Even if making the planning process slower and the preparation phase longer, this capacity building process was essential to engender ownership by the national government and engage them in the recommendations that came out of the survey, which need national authorities’ commitment for implementation at large scale.

What came out of it?

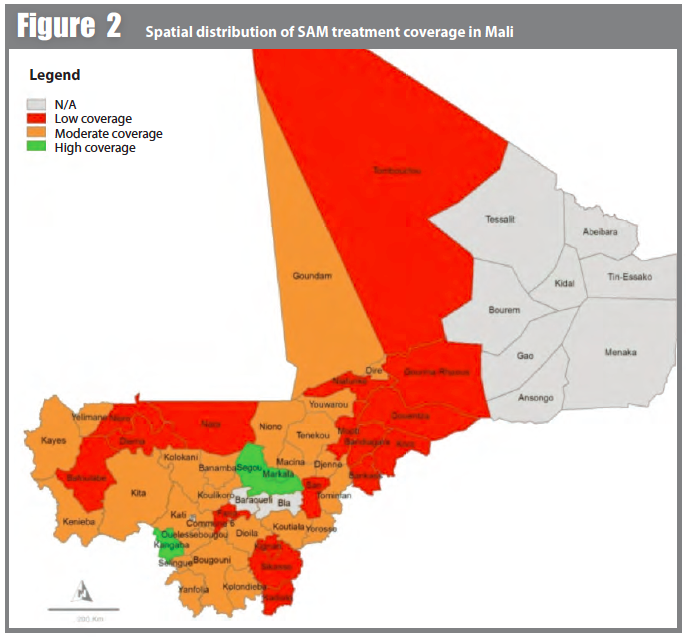

Based on a three tier classification of high (>50%), moderate (between 20% and 50%), and low (<20%), the survey found that 4% (n=2) of the 48 assessed Cercles had high, 46% (n=22) had moderate and 33% (n=16) had low point coverage levels. Coverage estimations could not be made for eight of the 48 surveyed Cercles because of a low sample size found during data collection. Figure 2 demonstrates the spatial spread of coverage across Mali.

The overall point coverage level was estimated at 22.3% (95% CI = 16.7%, 27.6%). Despite the fact that across the country coverage was found to be heterogeneous, providing an overarching estimate was deemed to be appropriate and relevant for advocacy purposes in order to demonstrate the need for increased response to SAM in country. At regional level, all the estimates fell below the SHPERE minimum standard of coverage for selective feeding programmes in rural settings (<50%).

The carers of children who met Outpatient Therapeutic Programme (OTP) admission criteria but were not enrolled were referred to the nearest health facility, and also interviewed about the reasons for their child not being in the programme. In total, 894 carers (all the non-covered cases) were interviewed. Table 1 gives an overview of the responses.

Table 1: Reasons given by carers for non-attendance (national figures) |

|||

Reasons given by carers for non-attendance |

Number of carers interviewed (n) |

Number of times mentioned (n) |

|

|

Demand side barriers |

|||

|

Lack of awareness about malnutrition |

Child is not considered as sick |

894 |

302 |

|

Amongst those who considered the child as sick, child not recognised as malnourished |

592* |

316 | |

|

Amongst those who recognised the child as sick/malnourished, lack of awareness of the programme |

276* |

138 |

|

|

Reasons given by carers who recognised their child as sick/malnourished and who were aware of the programme but still did not attend (n=138*) |

|||

|

Distance |

138 |

31 |

|

|

Lack of money4 |

138 |

21 | |

|

Husband refusal |

138 |

10 | |

|

No other person to take care of children |

138 |

6 | |

|

Carer busy/ high opportunity costs |

138 |

4 | |

|

Alternative Health Practitioners preferred |

138 |

4 | |

|

Defaulted due to travel |

138 |

2 | |

|

Programme organisation/quality |

|||

|

Previous rejection and fear of rejection |

138 |

15 | |

|

Child refused RUTF or RUTF did not help |

138 |

9 | |

|

RUTF stock out |

138 |

8 | |

|

Lack of programme information |

138 |

6 | |

|

Inter-programme interface problems (admissions in the wrong programme) |

138 |

6 | |

|

Other5 |

16 | ||

*Sample size calculations: 894-302=592; 592-316=276; 276-138=138

Lack of awareness about malnutrition, followed by lack of awareness of the programme, were the reasons most frequently reported. One third of carers (33%, 302/894) did not consider their child as sick and amongst those that did, over half (53%, 316/592) did not consider their child was malnourished. Amongst those that recognised their child was malnourished, half (50%, n=138/276) did not know where their child could be treated. This demonstrates that increased engagement with communities is needed in order to improve access, health seeking behaviour and eventual uptake of IMAM services in Mali.

Among those who knew their child was sick/malnourished and who knew where they could find treatment (n=138), major reasons at the community level were linked to distance to the health facility (n=31) and lack of money (n=21). Further data regarding distance was collected. In rural settings, median distance to travel to the nearest health facility varied from 7.5km to 15.5km. Those in Ségou travel on average half the distance compared with those in Mopti. In Bamako, the distances are very small but the time can be longer. At community level, other reasons evoked by carers concerned social norms, cultural beliefs and status of women (husband refusal, carer busy, alternative health practitioners, etc).

Finally, at programme level, various factors related to the organisation and quality of the OTP programme, which accounted for 44 of the answers provided, appear to highly influence, directly or indirectly, non-attendance. These include disrespect of admission and discharge criteria and admission to the wrong programme, rejection, Ready to use Therapeutic Food (RUTF) stock-out and lack of information provided to the beneficiaries (age of admission, appetite test, expected length of stay etc.).

The results of the survey were shared with a wide range of nutrition partners through a national workshop, providing a forum to analyse and discuss the results and ways forward. This forum was able to identify a set of activities related to increasing uptake of malnutrition treatment services, including more detailed qualitative research in five areas of low coverage identified by the SLEAC survey, which will lead into appropriate strategies of community mobilisation. The workshop participants also decided to set up a technical coverage group, where partner NGOs involved in supporting IMAM together with the government partners will share experiences and lessons learned on boosters, strategies that work and solutions to barriers that could be replicated at larger scale. Finally, partner NGOs committed to continue to monitor coverage following the national SLEAC through the implementation of annual SQUEAC surveys at health district level. In order to achieve this, capacity building and training of NGO and government partners will be organised with the technical assistance of CMN.

The experience of conducting a first national level coverage survey in Mali also allowed for significant learning around the process of implementing a large-scale survey of this type. Lessons learned included the need to allow sufficient time for planning, coordination and communicating with the national counterpart, especially when the country requires approval of the survey protocol by an ethical committee; the need to ensure very detailed, country specific and accurately costed logistics planning before the survey; the importance of ensuring the survey is fully planned and organised with the national counterpart and in the local language; and the need to conduct the survey during the period of high SAM rates to ensure sufficient sample size. It is also critical to ensure that all methodological questions are resolved, including the use of mid upper arm circumference (MUAC) only versus MUAC and weight-for-height for the survey in a country where admission criteria in the OTP programme include both MUAC and weight-for-height and the methodological issues around the inclusion of moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) coverage in the survey. The possibility of assessing MAM coverage together with SAM coverage was considered for one region at the initial stages of the survey planning at WFP’s request. However, the idea was abandoned considering the already numerous logistical and methodological challenges encountered during the survey implementation.

What next?

The results of the survey were used to identify priority areas for reinforcing programming, as well as for advocacy activities to increase support for nutrition to the health authorities, donors and the international community in general.

In most of the regions surveyed, the primary reason for non-attendance was found to be lack of awareness of acute malnutrition, of child illness and/or that IMAM services are available through the health system. Furthermore, a significant number of barriers were also identified relating not only to the supply but the demand for services. This is consistent with findings from similar assessments carried out in IMAM services around the world. In an effort to better understand the nature of awareness-related barriers and to explore alternative mechanisms for addressing it, further understanding of the existing social and community structures needs to be obtained in a systematic manner. In areas of low coverage, it is essential that more detailed data be gathered in order to be able to effectively modify programming to the context. In this regard, based on the results, the Government of Mali and UNICEF are in the process of establishing a qualitative research project in five areas of low coverage identified by the SLEAC in order to further investigate the barriers and boosters to coverage. The overall objective of the research project is to implement, document and evaluate qualitative investigations to further explore the reasons for non-attendance in the community with a view to adapt programmes and build a stronger community mobilisation strategy to achieve higher levels of access to treatment services.

For more information, contact Sophie Woodhead, email: s.woodhead@actionagainsthunger.org.uk

1 Lot Quality Assurance Sampling

2 http://www.coverage-monitoring.org/

3 The main investigator for this piece of work was Melaku Begashaw.

4 Not exclusively related to transport

5 Reasons unrelated to programme organisation such as mother sick, mother ashamed, security problem, discharged as non-responder, condition not serious, prefer traditional doctor.