How MSF is mapping the world’s medical emergency zones

Summary of news item1

Summary of news item1

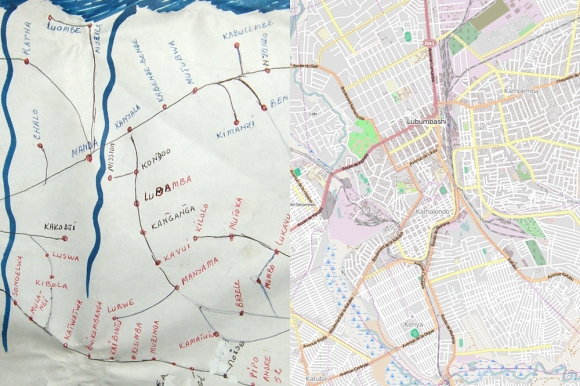

The Missing Maps project is a collaboration between MSF, the British and American Red Cross, and the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team that aims to create digital maps to log addresses for the “unmapped or undermapped” people of the world, who are often the poorest and most vulnerable. Launched on 7 November 2014, it aims to add an ambitious 200 million people’s addresses to the maps in the next two years with the help of volunteers worldwide (see Box 1).

Box 1: How MSF’s volunteers make the maps

Mapping involves four simple steps:

- Existing satellite images are loaded into OpenStreetMap software, a free world map that can be edited by multiple users (a wiki). It is a similar service to Google maps. Volunteer amateur cartographers, many enlisted through social media (check #MissingMaps on Twitter), can log in from anywhere in the world and use an easy tool to trace the outlines of buildings, roads, parks, and rivers over the satellite image

- This tracing lacks the names of streets or landmarks so local volunteers, often students or scouts, print out small sections and head out with a pencil to write down the names of streets and buildings

- Once complete, the maps are scanned back into OpenStreetMap and the labels are added to the map by more volunteers. The world then has free access to a validated map forever.

Anyone can volunteer their services on an individual basis or at sociable and technically supportive “mapathons.” At one of the first of such events, hosted by the UK Guardian newspaper in London on 7 November, 80 amateur cartographers along with 100 more remote volunteers, put the inhabitants of Baraka, a town in the Democratic Republic of Congo where malaria and cholera are endemic on the map.

Maps enable teams on the ground to provide a more rapid, more effective, and better planned response to vulnerable communities. Spatial epidemiology is critical to remain alert to and respond to disease outbreaks, such as cholera, as well as improve monitoring for and reaction to cases of less prevalent diseases, such as sleeping sickness. MSF can also create animated maps to show the spatial and temporal nature of a problem, e.g. animated maps were used to demonstrate how interruptions in the Haiti water network could be linked to spikes in cholera which then helped lobby government agencies for immediate, effective repairs to the network. It may be possible to do something similar in west Africa where the Missing Maps project has assisted the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team to map huge areas to support the Ebola crisis. The initiative has been well received by mapped communities.

Learn more and sign up to get involved at: http://www.msf.org.uk/missing-maps-project?

1 How MSF is mapping the world’s medical emergency zones. BMJ 2014;349:g7540