Participatory risk analysis and integrated interventions to increase resilience of pastoral communities in Northern Kenya

By Daniel Nyabera, Charles Matemo and Muriel Calo

Daniel Nyabera is Food Security and Livelihoods Programme Manager, ACF-US, Yemen Mission. Daniel has over nine years of experience managing food security and livelihoods programmes in South Sudan, Northern Kenya and Yemen.

Charles Matemo is Water Sanitation and Hygiene Coordinator, AC-US, Kenya Mission. Charles has over nine years of experience managing water sanitation and hygiene programmes in South Sudan and in Northern and coastal regions of Kenya.

Muriel Calo was Senior Food Security and Livelihoods Advisor in ACF’s New York office at the time of writing. She has a decade of domestic and international experience working on food security and livelihood issues in vulnerable settings, supporting ACF-USA country programmes in East Africa and Asia.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of USAID, which funded the 4 year drought response programme in Northern Kenya through the Arid and Marginal Lands Recovery Consortium that was comprised of ACF, Food for the Hungry International, CARE International, Catholic Relief Services (CRS) and World Vision International. Thanks also to Pascal Debons who provided peer review on an earlier draft of this article.

This article builds upon a case study by ACF available at: http://www.actionagainsthunger.org/publication/2014/09/acf-kenya-participatory-risk-analysis-integrated-resilience-pastoral-communities

Location: Kenya

What we know: Pastoralism is a key livelihood system that is threatened by recurrent drought in the Arid and Semi-Arid Lands (ASALs) of Kenya.

What this article adds: An ACF drought response in Northern Kenya involved improving drought preparedness capacity through rangeland and pasture regeneration, maintenance of water harvesting structures and livestock marketing initiatives. In emergencies, interventions can and should develop such local longer term capacities in addition to ‘classic’ short-term livestock assistance. Cash can be an important tool to achieve both ends.

Extensive livestock keeping or pastoralism is an efficient and productive livelihood system that has evolved to enable pastoralist households to survive and thrive in arid and semi-arid rangelands. However, cyclical droughts in the Arid and Semi-Arid Lands (ASALs) of Kenya continue to threaten mainly livestock-based livelihood resiliency. The context is characterised by extensive livestock-keeping (shoats, camels and cattle), a livelihood system that is increasingly under threat and at risk of dependency on aid as drought limits viable livelihood options outside of livestock production.

In Kenya, livestock production in the ASALs accounts for nearly 90% of the livelihood base and nearly 95% of household incomes1. With an estimated livestock resource base of 60 million animals2, the livestock sector in Kenya contributes 12% of the total GDP and 42% of the agricultural GDP3. Despite their contribution to the local and national economy, pastoralists in the ASALs of Kenya have been systematically marginalised for decades. The ASALs were significantly affected in 2011 by a drought which developed into a crisis, as well as the gradual erosion of community resilience and traditional coping strategies by successive shocks and limited development investments. A post-disaster needs assessment identified the entire period from 2008 to 20114 as one continuous drought, causing the loss of over US$805 million worth of physical and durable assets5.

In the 2011-2013 drought response in Northern Kenya, Action Against Hunger (ACF) intervened in Merti and Garbatulla Districts as part of the USAID-supported Arid and Marginal Lands Recovery Consortium (ARC). More than 85% of these districts were affected by the drought that saw up to 70% of livestock lost due to worsening pasture and browse conditions6. Livestock migration from Merti and Garbatulla also intensified due to depressed rainfall, while cases of insecurity and conflict rose.

ACF adopted an integrated approach for the drought response programme which focused on improving drought preparedness capacities of the communities in the two districts. The integrated programmes were designed to put the communities as the key actors, thus mobilising them to address collectively common risks and pursue risk reduction measures.

Enhancing community resilience

ACF supported the communities to analyse their risks and then implement practical interventions to increase their resilience. In this regard, communities identified three key areas of support that would mitigate total loss of livestock herds and associated livelihoods. These were: rangeland and pasture regeneration along strategic grazing corridors in the districts, construction and maintenance of water harvesting structures, and support to livestock marketing initiatives to facilitate herd control based on anticipated changes in climatic conditions.

Rangeland regeneration

Rangeland degradation is one of the major problems that pastoralists face in Northern Kenya, in addition to continuous bush encroachment that has reduced the size of available pasture, productivity of the rangeland and pasture quality. ACF supported local communities to conduct a resource mapping and stakeholder analysis. Information was collected from local institutions on the diverse resources in the rangelands of Garbatulla and Merti, and the groups (formal/informal) that have had a role to play in rangeland resource management. Migratory corridors were drawn and dry and wet season grazing areas mapped out within the livestock movement corridors.

With all stakeholders identified, ACF supported revitalisation of community rangeland management institutions with longstanding indigenous knowledge systems that focused on protection of the rangeland hotspots. To strengthen the local community capacities in the management of dry season pasture graze lands along the migratory corridors, technology transfer was largely based on experiential learning that firmly built on indigenous capacities and best practices. Focus group discussions were held along the migratory routes to determine strengths and capacities, skills and knowledge of the communities within the context of natural resource management.

At this stage, cash based interventions were used to protect identified hotspots (dry season graze lands) mainly through pasture regeneration. Cash was used to stimulate community participation in pasture regeneration in the dry season grazing blocks in an area that was coming out of a long drought. A total of 1346 Cash for Work (CFW) beneficiaries received an average of 3.75 USD for each of three days worked in regenerating the pastures. As a result, more than 15,140 USD was injected into the local economies from the cash disbursement. Pasture regeneration activities involved reseeding by either over-sowing into existing vegetation with a superior species or complete reseeding of denuded land, depending on the condition of the pasture. In both cases, the reseeded land was then enclosed and utilized as per a grazing plan.

These activities were implemented along with training of Rangeland Management Committees on land use and implementation of appropriate grazing management regimes. For example, community action plans on pasture utilisation in the dry and wet season were developed, with dry season blocks being the main focus for reseeding interventions. The use of perennial seeds for reseeding of denuded pastures was also recommended since perennial grasses have good self-seeding ability; with proper management they can establish and spread quickly to give good cover. In this regard, Cenchrus ciliaris was identified and utilised.

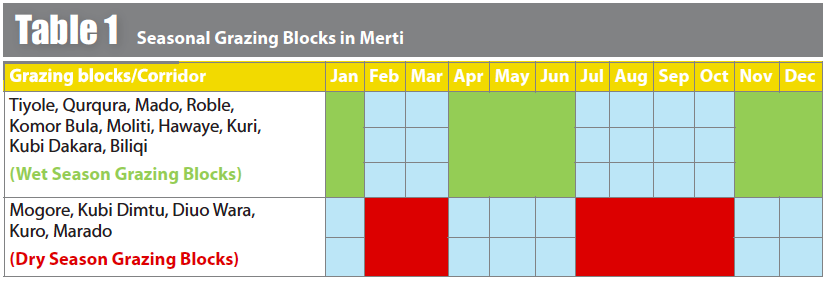

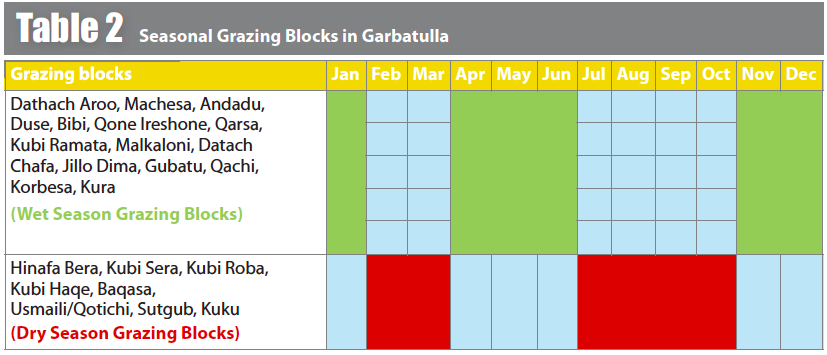

Training and planning with the committees was done as a safeguard to protect management of the regenerated pastures. A rangeland management plan specifying the roles and responsibilities of the rangeland management institutions was drawn up, providing information on the resources and their condition and an outline of the rangeland management processes that will be followed, including monitoring and evaluation of adaptive management. Seasonal pasture availability was analysed based on indigenous technical knowledge of the pastoral communities in the programme area and covered both wet and dry seasons. A grazing plan was drawn up to regulate herd mobility between dry and wet season pastures in Merti and Garbatulla Districts as shown in Tables 1 and 2.

During rainy seasons, pastoralists were in favour of leading herds to very distant pastures in areas highlighted in the seasonal plan to ease grazing pressure. In the dry seasons, noting that the lack of surface water would force herds back to the pastures around the wells, rangeland management committees proposed to have milking herds grazed in the inner circle around the wells, while other animals were kept in the outer circle. The plan was sensitive to the need of the herders – to be in close contact with their herds, and the natural environment.

In addition, the plan highlighted the communal resource-tenure regimes for extended user groups to coordinate access to shared grazing resources in normal years and to allow for negotiations over use of key resources during times of scarcity. This also acted as a guide to other herders to know exactly where to move their animals in order to find available forage and water resources and subsequently mitigating against pasture related conflicts.

While communities prefer to utilise the regenerated pastures in the dry season for grazing, future engagement would focus on supporting the resource management committees to address seasonal deficiency by conserving surplus forage during the high fodder availability period.

Today, restoration of pastureland is one of the principal drought mitigation measures being implemented by the communities with additional support from the newly created county government of Isiolo. A total of nine reserve pastures of 12ha each were regenerated along migratory routes between Garbatulla and Merti District, thus improving access to fodder for at least 23,000 livestock who traditionally utilize the dry season grazing blocks where the reserves are located.

Apart from improving acceptance of ACF participatory strategy in rangeland management, the cash based pasture regeneration exercise promoted information flow and cascading of the roles and responsibilities of Rangeland Management Committees from location to village level, which was essential for mitigating consequences of poor rangeland management.

Simple decision support tools and local level monitoring mechanisms were developed in order to inform decision making, trigger early warning for livestock marketing and inform herd control decisions especially when pasture availability is inadequate to carry herds over to the next season. The main early warning indicators used for development of support tools to monitor pasture include changes in vegetative cover through visual biomass estimates, and changes in water cycle and recharge levels.

An analysis of potential synergies between various land use strategies in the context of Merti and Garbatulla was conducted to improve productivity of the rangeland. This specifically targeted the dry season grazing blocks which were mapped out to guide implementation of integrated water resource management interventions and exploit livestock marketing potential.

Water harvesting for livestock

Water harvesting for livestock

With the migratory routes clearly mapped out, ACF rolled out a CFW programme that supported rehabilitation and construction of livestock water points to reduce livestock and human deaths at times of drought. The community provided locations for the water pans rehabilitated through the project. Key considerations were the grazing patterns and corridors to the market. It is critical to note that the community was against establishment of new water points without thorough consideration of the effects to the rangeland. The programme therefore concentrated on improving on prioritised water pans. An estimated 186,440 livestock and 40,845 livestock owners benefited from rehabilitated or newly constructed water sources which include water pans, shallow wells, borehole, water storage tanks and access points (livestock water troughs), while 1359 people participated in CFW water point rehabilitation and construction activities.

The CFW programme assisted households to meet immediate needs during a vulnerable period and created employment opportunities for the unemployed, while the rehabilitated and constructed water points ensured retention of milking herds near the settlement to provide required milk for the children and surplus taken to market for income and made it possible to de-silt more earth-dams. As a result of cash inflows from CFW activities, purchasing power of the beneficiaries increased and in turn markets were stimulated. A majority of participants, after action review focus group discussions, asserted that in the unfortunate event of a new drought, they would suffer less because the implementation of activities under the economic asset development component of the ARC project (see earlier) will reduce the risks and mitigate negative effects. “We have no fear of the threat of drought as we have learned to preserve and store pasture, grow and preserve food” responded a participant during a focus group discussion session in Garbatulla7.

Improving livestock markets

In the ASAL of northern Kenya, there are significant barriers and obstacles to improving household income due to climatic conditions, disabling government policies, poor services, and low terms of trade between livestock products and staple foods. Despite these barriers, a significant proportion of those living in the ASALs retain valuable and profitable assets in the form of livestock. Pastoral communities in northern Kenya face severe challenges in the marketing of their livestock however, including long distances and poor roads in reaching marketing infrastructure, lack of organized market days, limited connections between traders and livestock owners, and poor market awareness. ACF’s livestock marketing initiatives in Isiolo County sought to address these issues by contributing to greater sustainability and efficiency of the marketing system.

ACF’s assessment of livestock markets in Garbatulla district in 2010 attributed the cause of dilapidation and abandonment of livestock markets to poor placement decisions, weak and corrupt maintenance revenue collection systems, lack of ownership and insecurity. With the livestock migratory routes already mapped out by the Rangeland Management Committees, ACF supported participatory decision-making on appropriate livestock market locations within the migratory routes with a view to rehabilitating ‘best bet’ market yards that would support strategic destocking of household herds. This should also open up the location to other districts which would then assure the pastoralists of income in the face of drought. Site selection was based on ensuring that there was adequate demand from both traders and producers. Critical location factors for producers that influenced decision making on market rehabilitation included: the market being within a reasonable trekking distance, the site being accessible without infringing on other rangelands, and accessibility to livestock water sources being nearby. In addition, market placement decision making took into account the locations of other markets to ensure they do not undermine each other.

With ACF support, two livestock markets were rehabilitated in Garbatulla and equipped with the necessary infrastructure that included a sales yard, loading ramp, sanitation facilities, water sources (for livestock water), shading/resting area for livestock, crushes8 for isolating and examining livestock and office infrastructure. On average, the rehabilitation works cost 20,000USD per market. To sustain efficient management of the rehabilitated livestock markets, ACF facilitated the creation of two Livestock Market Management Committees (LMMC) comprised of local community representatives responsible for managing the markets. Inclusive representation in these committees was guaranteed by representation from key stakeholders drawn from livestock traders, community based animal health workers, peace committee members, environmental management committees, registered women groups and livestock producers. The LMMCs were responsible for setting livestock market days, promoting market awareness (destocking campaigns in the face of droughts), recording livestock sales data, participating in resolution of conflicts and overseeing maintenance of livestock market infrastructure.

In June 2012, ACF partnered with Food for the Hungry (FH) Kenya and SNV Netherlands to lobby for a livestock market co-management model in which local communities share roles and revenue collected with the county council. The model fosters sustainability and efficiency through community ownership and re-investment of funds into improving market infrastructure and support to market processes, based on a revenue-sharing formula whereby the collected cess (tax) is shared between the respective county councils and the Livestock Marketing Associations (LMA). Responsibilities for personnel and repair costs incurred on market days are also shared between the two entities. Prior to the development of this model, no amount of the collected revenues was ploughed back into the market. The model ensures that a considerable amount of the revenue collected is committed towards market maintenance and provision of essential services such as security, loading, and effective structures. The model was adopted in Isiolo County following signing of a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between the County Council of Isiolo & Oldonyiro LMA, as this was the selected livestock market for piloting before replication and roll out in four ARC funded livestock markets in Isiolo County.

Significant impact on County Council and LMA revenue and capacity to manage sites was noted with the introduction of the livestock market co-management model:

-

Increased revenue raising capacity: Before livestock co-management in Oldonyiro, the County Council of Isiolo collected Ksh.791,780 (USD 9,897) over 28 market days (May 2011-June 2012). This revenue included cess from auction, barter and export fees. Following the introduction of co-management, Ksh.465,355 (USD 5,817) was collected during the first 3 market days (seven weeks only), representing 60% of one year (28 market day) collections before co-management9.

-

Reduction of operation & maintenance costs: Under the new model, a total of Ksh.90,600 (USD 1,133) was spent on operation costs to collect a total of Ksh.465,355 (USD 5,817), representing 19% of total cess income generated; compared to 42% average daily expenditure for market days before co-management.

-

Sharing of revenue: Both parties got their share as agreed in the MOU. During the period of seven weeks of co-management, County Council of Isiolo received a total of Ksh. 257,605 (USD 3,220) while the local community got Ksh.117,241 (USD 1,466) representing 69% and 31% respectively after deduction of daily expenses

In Figure 1, expenditures are expressed as a percentage of total income received for market days before and after co-management. The weekly maintenance cost was an average of Ksh.13,000 against average net revenue of Ksh.70,000. This significant change in revenue is an indication of viability and sustained operations and management of livestock markets in the absence of external support.

Figure 1: Trends in expenditure for market operations as a percent of total income

Lessons for sustainability

Investments in rangeland management are likely to be sustained if follow-up actions are taken:

-

Assessing the pasture seed value chain and promoting the informal sector to carry out seed production/bulking functions

-

Supporting grassroots trainer of trainers’ workshops to equip farmers and extension workers with methods, skills and knowledge to design, facilitate and implement seed multiplication initiatives in their respective areas. It involves participatory approaches based on experiential learning techniques and participatory training methods provided by government research actors.

-

Supporting establishment of seed production plots where pastoralists are provided with the starter grass seed to start them off. In this regard, pastoralists will maintain reseeding of dry season grazing blocks, harvest seeds and store for regeneration in the event of an imminent drought. Technical backstopping is required from government research actors to assist pastoralists in dealing with emerging challenges in the field especially in grass management, seed harvesting and storage.

Considerations for sustaining investments in water point infrastructure:

-

Local artisans provide technical skills for minor maintenance and running of boreholes, with major maintenance carried out with support from the County (at a fee). Fuel expenses and other running costs are covered through community contribution to a common fund. During the dry period, expenses drastically increase, sometimes exceeding existing community resources. Tariffs reflecting seasonal needs, regular fund contribution and effective fund management remain essential for ensuring continued service on borehole water provision.

-

Community prefers water pans due to unhindered water access, especially during the dry season, when large herds water from the same water points. Less conflict was noted at the water pans due to every pastoralist getting water unrestricted for the livestock. Considering rain scarcity in this location, it is critical to maintain harvesting of adequate volumes every season through silt removal and adequate fencing.

-

Community contributions towards maintaining the water pans is considered a low priority due to low frequency of maintenance needs, making it a challenge for longer term sustainability of the infrastructure. Even though water pans near settlements are able to raise revenue from livestock accessing water, those in the interior of rangeland lack revenue generation due to lack of follow-up on water payment. If water pan and other water source maintenance needs are considered as an imbedded service cost for optimal rangeland management, this would allow funds to be recovered through other existing services such as markets. Costs could be co-shared between the community and the County Council.

Considerations on sustainability of livestock market co-management model:

-

Putting local pastoral communities at the centre of decision-making in the management of the livestock markets not only resulted in vibrancy of the livestock markets, but also stimulation of the local economies and improved social welfare. Communities, including the youth, have bought into livestock trade to promote pastoral production systems that are sensitive to drought.

-

The co-management has played a critical role in facilitating the livestock value chain. Improved market infrastructure as a result of implementing the livestock market co-management model enabled market access to livestock value chain actors. The trickle- down effect was felt on employment and introduction of platforms to transmit market information outside the market catchment area. Informal employment opportunities were created such as tea vending, catering, animal trekking and branding.

-

Replicability of the co-management model is attributable to community participation as the central pillar of the model. The communities served by the model were easily able to identify themselves with it, contributing to the success rate of the model in livestock markets in Northern Kenya.

Conclusions

As climate change puts growing pressure on livelihoods in Northern Kenya, pastoralism is becoming more economically productive as a result of these types of integrated approaches to mitigating drought related risks. It is observed that pastoralists in the ARC programme areas are continually finding new forms of managing and using resources to adapt to drought. The experience of the programme shows that even in emergency contexts, interventions can and should seek to build and develop local capacities to manage appropriately key livestock assets such as rangelands and water, using local and indigenous structures, knowledge and good practice – in addition to providing more classic short term emergency assistance such as destocking or feed and water distribution. Cash can be an important tool to achieve both ends simultaneously. There is strong evidence that in terms of economic growth, secure livelihoods and environmental sustainability, pastoralism is the most appropriate economic activity when local capacities are harnessed to design drought risk reduction interventions.

For more information, contact: Pascal Debons, ACF-US Disaster Risk Management & Resilience Technical Advisor, email: pdebons@actionagainsthunger.org

1 Kenya Ministry of Livestock Development Session Paper #2 National Livestock Policy, November 2008

2 AU-IBAR – Animal Health and Production in Africa, 2009

3 Quick Scan of the Dairy and Meat Sectors in Kenya, Issues and Opportunities, SNV, 2010

4 The 2005/06 drought affected four million people in the ASALs and an estimated 50-60% of livestock (shoats, camels and cattle) died. Many households and communities had only started to recover when 2007/2008 brought triple shocks of post-election violence, high food and fuel prices and El Niño related flooding.

5 Kenya Post Disaster Needs Assessment (PDNA) 2008-2011 Drought. Republic of Kenya

6 National Drought Management Authority – Drought Monitoring Bulletin December 2012

7 ARC Evaluation Report - July 2013

8 A strongly built stall or cage for safely examining livestock.

9 Oldonyiro Livestock Market Co-Management Model (Quarter 1 Report) by FH Kenya (2012)