Experience of intersectoral integration in an NGO nutrition programme and a typology for programme design

By Aaron Buchsbaum and Jody Harris

Jody Harris is a Senior Research Analyst in the Poverty, Health and Nutrition Division of the International Food Policy Research Institute. A public health nutritionist, her research interest is primarily around the theory and practice of linking the agriculture and health sectors for nutrition outcomes, including the study of intersectoral coordination in government and NGO systems.

Aaron Buchsbaum worked for two years with the USAID SPRING project as a research assistant and as a knowledge management coordinator. Aaron has a technical and academic background in international public health and clinical nutrition, with an interest in agriculture and health policy. He served as a U.S. Peace Corps volunteer in Burkina Faso from 2008-2010, where he focused on community health in a town of 5000 people.

This study was funded by the USAID Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) Project, with additional funding from the CGIAR Research Programme on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health (A4NH).We would like to thank the HKI/Burkina Faso team for their invaluable support, as well as the data collection team and the study respondents. We also thank colleagues at IFPRI, SPRING, and HKI/Washington who contributed critical feedback throughout the research.

This article draws upon the following report: Harris, Jody and Aaron Buchsbaum. 2014. Growing Together? Experiences of Intersectoral Integration in an NGO Nutrition Program: A Study of HKI’s Enhanced Homestead Food Production Model in Burkina Faso. USAID/Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) Project, Arlington, USA. https://www.spring-nutrition.org/publications/reports/growing-together-experiences-intersectoral-integration-ngo-nutrition-program

Location: Burkina Faso

What we know: Multi-sectoral efforts are needed to address malnutrition. There is limited definition of and evidence on how to implement intersectoral actions.

What this article adds: A qualitative assessment of HKI’s multi-sectoral homestead food production programme explored experiences of how intersectoral action was implemented in practice. The study found that, although the project was designed for beneficiaries to benefit from harmonised agriculture and nutrition activities, little attention was paid to ways programme staff could work collaboratively; many found ways to work together in an ad-hoc manner, varying implementation over different programme areas. The analysis reveals a typology of different ‘modes of integration’ which can help programme designers explicitly address ways of working across sectors, which should then be monitored and tested for impact.

Malnutrition is fundamentally multi-causal, and efforts to comprehensively address it will therefore necessarily be multisectoral. Two sectors in particular are known to have a direct influence on the underlying determinants of malnutrition: the health sector, in particular public health and hygiene; and the agriculture sector, which generates food and income. But ‘development’ and ‘emergency’ nutrition actors are wrestling with how to bring these discrete and differently-oriented sectors together. This case study documents how intersectoral coordination happened in a homestead food production project for improved nutrition outcomes in Burkina Faso, and what this tells us about design of intersectoral programmes more broadly. The analysis offers an early ‘typology’ of ways to approach integrated projects, which may assist those designing programmes to better articulate how implementers are expected to work across sectors.

Defining and measuring ‘integration’

There is now a fairly comprehensive literature on ‘what works’ in reducing undernutrition, including integrating actions across several different sectors1. However, partly due to challenges in the definition and measurement of ‘integration’, there is a limited literature base from which to gather evidence on how to implement these intersectoral actions. Modes of intersectoral working- or how the sectors can or should interact - are not well defined in the few intersectoral non-governmental organisation (NGO) programmes available for review. Where definitions of integration are made explicit in different studies, they appear to form a continuum moving from less to more coordinated working; each stage along this continuum represents different levels of interaction between actors in different sectors, but definitions are often unclear. There is a need for further research on different modes of integration in practice, particularly as multiple sectors are increasingly being programmed together.

Context

Burkina Faso is a Sahelian country and, as is the case with many of its neighbours, food insecurity is a major challenge; agricultural production is subject to cyclical crises of drought, heat waves, and flooding. Food access is therefore variable, with an annual hunger season falling between June and September during which staple grain stores are low, and availability of fresh foods varying over the year. Alongside poor access to diverse foods, child feeding practices are often seen to be inadequate in the country, with very low rates of exclusive breastfeeding in infants and late introduction of complementary foods. As a result, levels of chronic undernutrition (manifesting as stunting) remain at around 45 percent.

In response to these challenges, Helen Keller International (HKI) implemented its flagship Enhanced Homestead Food Production (E-HFP) programme model between 2009 and 2012, targeting women and children in 1,200 households across 30 villages. Marrying the health and agriculture sectors within its programmes, the project provided support for home gardening and small animal production alongside messages on Essential Nutrition Actions (ENA). The aim of the E-HFP model is to expand access to nutritious food and to improve knowledge and practices for better nutrition outcomes, specifically iron status and child growth. The project was targeted to mothers of children under two years of age and was designed to 1) increase the availability of micronutrient-rich foods through increased household production of these foods; 2) generate income through the sale of surplus production; and 3) increase knowledge and adoption of optimal health- and nutrition-related practices, including the consumption of micronutrient-rich foods. These pathways were supported by homestead food production activities and nutrition behaviour change & communication (BCC) activities and delivered by a variety of NGO, government, and volunteer trainers.

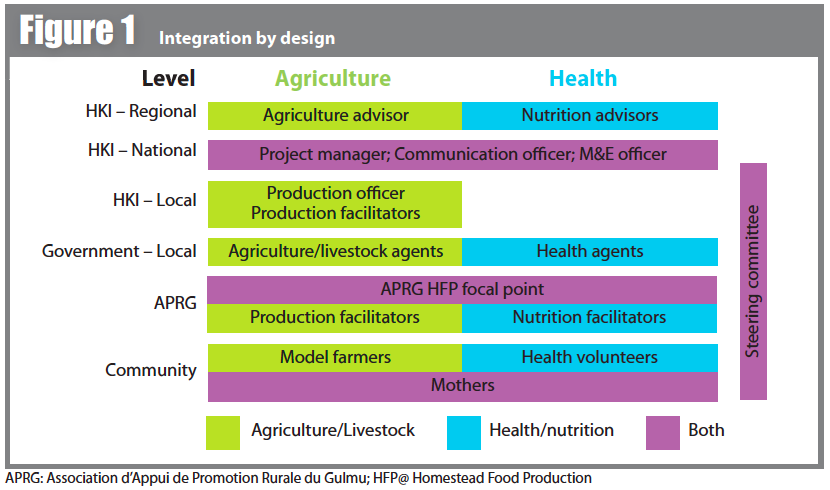

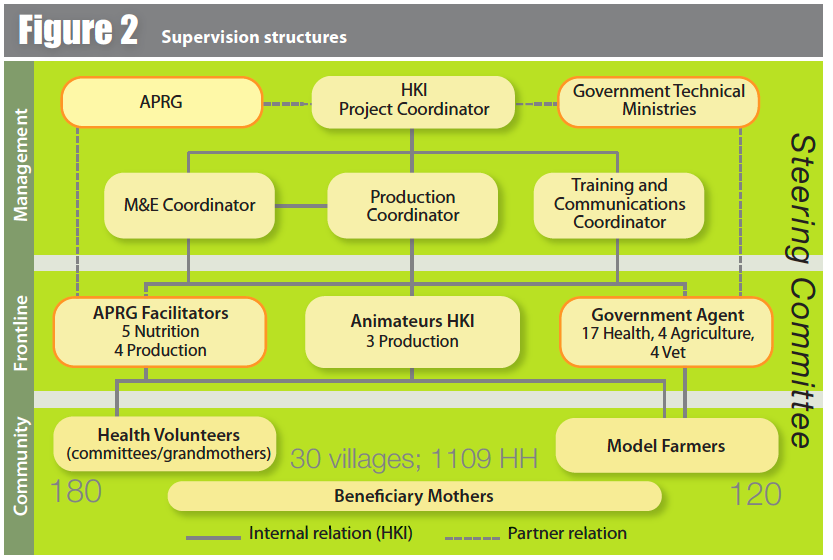

A number of levels of staffing were involved in the E-HFP project: managers from HKI, partner NGOs, and local government ran the project, overseen by a steering committee. Government field agents and NGO facilitators provided cascades of training and inputs to community-level farmer leaders and health volunteers, who in turn delivered the information to mothers of small children through Village Model Farms and women’s groups. These different levels of participant as well as project beneficiaries are the respondents who informed this study, providing their thoughts, experiences, and insights on the design, implementation, and monitoring of an intersectoral programme from the point of view of those working within it.

At the end of the 3-year program cycle, an independent impact evaluation conducted by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) found nutritional impact was limited to increases in children’s dietary diversity, intake of iron-rich foods, and small increases in haemoglobin concentrations among young children, but no reduction in stunting2. One major conclusion of the study was a need for stronger links to water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) programming3, adding an additional sector and therefore further need to understand how sectors can work better together.

Methods

This was a qualitative study, exploring experiences of intersectoral integration in HKI’s E-HFP programme in Burkina Faso. The overall research question was: How and why did different sectors integrate at different programmatic levels within HKI’s E-HFP project in Burkina Faso? Within this, seven sub-questions were articulated4; for this article, we choose to focus especially on the following: To what extent was any designed-for integration implemented at each programmatic level; how much integrated working was implemented even in the absence of integration in design? The study was exploratory, and analysis focused on what could be learned about implementing intersectoral action to inform similar future projects.

As part of the planning process for this study, an understanding of how integration was planned within the design of the programme was required. Various documents associated with the programme were reviewed to provide background, and an initial scoping visit to the programme site was conducted, after which a visual tool was constructed to show how integration was envisaged at different levels in initial project design (Figure 1). Subsequently, a published framework5 guided the creation of a full interview guide, and interviews were undertaken at different levels (management, government and NGO field staff, and beneficiaries) to capture (1) information on any planned integration, (2) how this was realised in implementation, and (3) how these integration efforts were monitored. Interviews were undertaken by a small team of four Burkinabé interviewers (two male, two female) familiar with both French and local languages; each had previously worked on IFPRI qualitative research, and full training on interview methods was given. Data were analysed using framework analysis, with themes compared between respondents of different categories (agriculture versus health sector workers, field workers versus managerial staff, etc.).

Findings

Design and organisation

The project was not designed to integrate sectors at all levels (Figure 1), and management structures reflect the mostly separate sectoral supervision and reporting lines at field level (Figure 2). While budgets in the initial plan were split evenly between agriculture and nutrition, managers reported that in reality, a far larger proportion was spent on agriculture—particularly agricultural inputs for community workers on the agriculture side—than was spent on nutrition BCC/ENA. The major structure in place for intersectoral coordination was the Steering Committee, comprising representatives for each sector at each level from management to beneficiaries. It was convened every six months to discuss project experiences, problems, and results, but was not felt to have achieved its full coordinating potential, and was said to be mostly a reporting body between different parts of the programme that also made decisions around process issues such as levels of procurement.

Management systems appeared to have evolved as the project progressed, adapting to the competencies of managers on the ground, and there was no reported monitoring of whether or how different sectors were interacting. In the design of the project, there was no HKI manager for the health side below the communications manager in Ouagadougou. Some respondents felt that this left a gap in technical and supervisory capacity on the health side, with BCC/ENA activities left entirely to the local partner NGO6 in terms of implementation. An innovation in intersectoral supervision was the advent of joint supportive supervision visits: Government and NGO managers from both sectors (health and agriculture) undertook periodic tours together of Village Model Farms to critique and find solutions to issues relating to different sectors. Overall, management was kept within separate sectors both by design and by implementation, other than the intersectoral Steering Committee and joint supervision visits every six months.

“There are no difficulties [in integrating the sectors from a management point of view]; it’s just that the managers [at HKI] haven’t seen that it is necessary. HKI has a different manager for each sector, who attends only that sector’s training. If there was a strategy for integration, it would be very interesting.” —NGO manager

Overall, the major conceptual basis for integration was not made explicit, but appears to have been through harmonised messaging; while programme managers designed messages to be complementary (and there was intersectoral oversight at the managerial level within each NGO), actors from separate technical sectors were asked to deliver messages separately in the field, and it was at the level of the beneficiary mother where all messages came together. It was therefore down to each mother to put these messages together and create improved nutrition through improved practices, preparation, and consumption of the nutrient-rich foods she produced.

Field-level integration

Field-level integration

HKI identified and trained government agents from agriculture and health to provide assistance to frontline workers in the form of specialised training and occasional supervision. Government agents from both sectors were evenly split in terms of their feelings around time pressures for this work, which was in addition to their formal roles. Some felt that they had too little time available for this additional work, that it upset their regular work, and that it was particularly time consuming to gather individuals for meetings or trainings. Others reported no difficulties in undertaking this additional work and were able to organise one set of roles around the other with no conflict with other activities.

Frontline respondents at all levels reported that they were not required by their supervisors to work together in the field with those from other sectors. However, some reported working together anyway; this varied by level, but general motivation for working with colleagues from other sectors was high. Government agents in particular were not told by their supervisors to meet across sectors, and according to these respondents, they never did.

NGO facilitators were also not required to work together in the field, although they were supposed to hold monthly planning meetings together. Some reported working together anyway, for practical reasons (such as companionship on journeys or better planning of coherent training sessions) although this was not mandated centrally, so it was down to individuals to decide and organize joint working. While joint field visits were reported on occasion, few facilitators reported holding joint trainings as a regular event.

At the community level, the picture appears to be more confused; several community-level workers professed that meeting with those working on the other side of the project was not ordered and did not happen; others said it was not ordered but happened anyway; still others said meetings across sectors were ordered and facilitated by supervisors. Again, processes appear to have been ad hoc, depending on the level of initiative taken by supervisors and individuals. Integration in this form was likely to have been uneven throughout the project areas.

“No, we never initiated a joint activity together. The health volunteers did their work; we did ours. There was no confusion between tasks.” - Village lead farmer

“No, it wasn’t planned, but we worked together. The farmer leaders helped often, and I supported them on certain occasions as well. That was a personal initiative and allowed us to pass certain information in a collaborative way, and to show us where our work needed to be completed.” - Community health volunteer

At all levels, the two main benefits of integrated working expressed by respondents were that it capitalised upon collective strengths to deliver complementary interventions, and promoted learning between individuals; disadvantages expressed particularly at higher levels were around practical issues, such as timing of getting to the field together, and work pressures.

Conclusions: thinking through modes of integration

Conclusions: thinking through modes of integration

The assumption in all homestead agriculture-nutrition programmes, including HKI’s E-HFP project, is that the provision of interventions to improve agricultural production, health behaviour, and empowerment will create synergies that help to improve nutrition outcomes. What is often less explicitly articulated is exactly how these synergies are expected to occur; it is likely that the form of integrated action chosen, and the assumptions underlying these choices, would affect achievement of programme goals. This case study describes how integrated working occurred in the context of one particular programme and sheds some light on how those involved in the E-HFP activity experienced intersectoral working, and suggest some lessons going forward.

While the overall intersectoral goal of delivering harmonised messages and activities to project participants remained throughout the design and implementation of the E-HFP project—and project staff at all levels were generally motivated to work with those from other sectors—intended modes of intersectoral working in practice were not clear in the project design. This is to be expected with a new project where ways of working across sectors are being learned at an organisational level, and aligns with findings from other assessments of intersectoral working. But without explicit attention to these different potential modes of working from the start, intersectoral processes become ad hoc and confused.

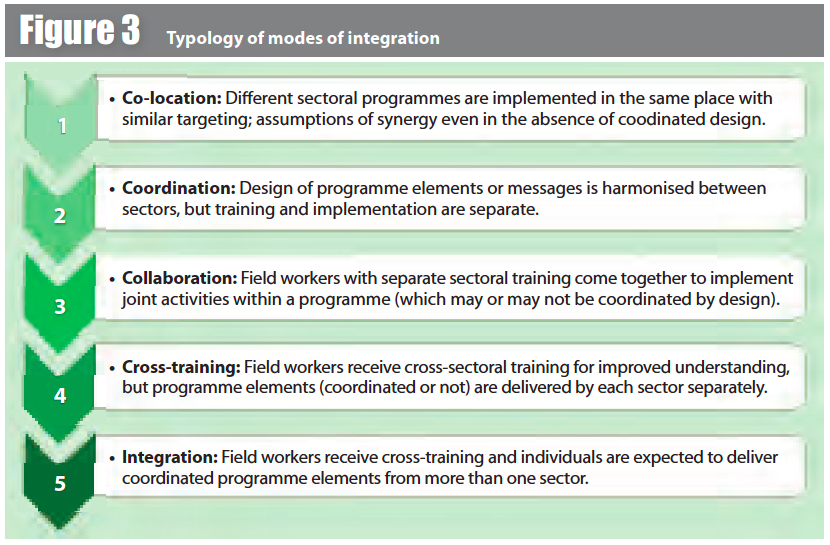

Several distinct modes of integration emerged from the interviews and subsequent analysis. These were seen with respect to approaches to targeting, message design, cross-sectoral training, and joint implementation. We have labelled the different modes with words found often in the intersectoral coordination literature but rarely defined; this is not intended to tie a particular word to a particular meaning forever, but only to facilitate this explanation and take discussion forward (Table 1). What emerged ultimately is a tentative typology of different modes of integration (Figure 3) which may help project designers be more explicit about the expected ways of working across sectors, and likewise help researchers test these different modes with a degree of standardisation.

Table 1 Definitions of words in the typology |

||||

|

Similar targeting? |

Harmonised design? |

Cross-sectoral training? |

Joint implementation? |

|

|

Co-location |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

|

Coordination |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Collaboration |

Yes |

Yes/No |

No |

Yes |

|

Cross-training |

Yes |

Yes/No |

Yes |

No |

|

Integration |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes* |

*Implementation is by a single cross-trained individual

Each of these modes of intersectoral working is being used in parts of the E-HFP project. There would be pros and cons to each mode of integration in different contexts (such as availability and initial level of understanding of actors from different sectors, project aims, existing extension systems etc.); these would need to be thought through for each particular project, and one or more modes of integration chosen accordingly.

In future projects involving cross-sectoral working, programme designers and managers should pay explicit attention to modes of integration at the design stage, thinking about strategies as well as day-to-day processes for collaborative working, about how to track and monitor whether these are happening during implementation, and about how to assess whether different modes affect impact. This learning can start to improve ways of working in complex intersectoral programmes such as those required for tackling malnutrition.

For more information, contact: Jody Harris j.harris@cgiar.org

1 Ruel, Alderman at al, 2013. Nutrition-sensitive interventions and programmes: how can they help to accelerate progress in improving maternal and child nutrition? The Lancet 382 (9891): 536–551

2 Dillon et al, 2012. Impact evaluation of HKI’s E-HFP program in Burkina Faso. IFPRI, Washington DC

3 HKI has added this component in their current round of programming, and a multi-country study is assessing impact in collaboration with IFPRI. See http://www.ifpri.org/book-741/node/10328 for details.

4 These questions, along with the full study design and findings, can be found in the full study report at http://www.spring-nutrition.org/publications/reports/growing-together-experiences-intersectoral-integration-ngo-nutrition-program

5 Garret and Natalicchio, 2012. Working multisectorally for nutrition. IFPRI, Washington DC

6 Association d’Appui de Promotion Rurale du Gulmu (APRG)