Management of hypertension and diabetes for the Syrian refugees and host community in selected health facilities in Lebanon

By Maguy Ghanem Kallab

By Maguy Ghanem Kallab

Maguy Ghanem Kallab is the health coordinator of HelpAge International in Lebanon. She holds a Master’s degree in Public Health and is currently pursuing her doctorate in Health. She has 10 years of professional experience in the public health field.

Maguy Ghanem Kallab is the health coordinator of HelpAge International in Lebanon. She holds a Master’s degree in Public Health and is currently pursuing her doctorate in Health. She has 10 years of professional experience in the public health field.

The author is very grateful for the support and input of Dr Pascale Fritsch, Humanitarian Health and Nutrition Adviser, Help Age International. The author also extends thanks to Help Age International and to the Disaster Emergency Committee for funding the project and supporting services for Syrian refugees and vulnerable Lebanese. The author gratefully acknowledges the contribution of all the partners to the success of the project; Amel Association International, American University of Beirut/Centre for Public Health Practice, Medecin du Monde and the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) – Lebanon.

Location: Lebanon

What we know: Non-communicable diseases are a major and growing public health problem in low and middle income countries; this is relevant for protracted crisis situations.

What this article adds: In August 2014, Help Age International and partners began a clinic-based health project (prevention and management) in four regions of Lebanon targeting Type II Diabetes and hypertension in the Syrian refugee population and the vulnerable Lebanese host communities aged over 40 years.From November to May 2015, 1,825 patients were enrolled (two-thirds were Syrian refugees); 46% with hypertension, 27% with diabetes, and 27% with both. It has been a successful collaboration amongst partners; coordination and communication proved critical. Challenges include insecurity, transportation costs and workload.

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) constitute a major global public health problem expected to evolve into a staggering economic burden over the next two decades1. The upsurge in NCDs is related to the epidemiological transition from communicable to NCDs, demographic change related to the increased longevity, urbanisation and globalisation that has resulted in exposure to ‘junk’ food, increased consumption of alcohol, less physical activity and an overall unhealthy lifestyle.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), the four common NCDs are cardiovascular diseases (CVD), cancers, diabetes and chronic lung diseases. These diseases share common modifiable risk factors including smoking, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity and alcohol abuse. In 2012, cardiovascular disease was the leading cause of NCD deaths, causing 17.5 million deaths worldwide2. Two important risk factors CVDs are hypertension (HTN) and diabetes mellitus (DM) that are increasing in epidemic proportions globally. HTN affects about one billion people worldwide and is expected to reach 1,561.56 billion by 2025.3 DM affects 366 million people around the world and according to the International Diabetes Federation, one in 10 people will suffer from DM in 2030.4

The burden of NCDs is rapidly yet disproportionally increasing, with the highest impact in low and middle income countries (LMIC). In 2004, NCDs accounted for 60% of the 59 million deaths world-wide5, rising in 2012 to 68% of the 56 million global deaths.6 Nearly three quarters of NCD deaths occur in LMICs; about 48% of deaths occur before the age of 70 years.7 Furthermore, it is estimated that by 2030, NCDs in the LMICs will be responsible for three times as many disability adjusted life years (DALYs) and nearly five times as many deaths as communicable diseases, maternal, perinatal and nutritional conditions combined.8

In the Arab countries, data for NCDs and their risk factors are limited but there is clear evidence that risk factors for the development of NCDs are on the rise. According to WHO, physical activity in the Mediterranean region is very limited and the region ranks the highest for sedentary lifestyle among school-going adolescents (87.5%) and second highest for adults 18y plus (31.1%)9. Low physical activity in the Arab region has been attributed to the lifestyle changes that accompanied urbanisation and the cultural constraints of the conservative communities where women are more likely to stay homd.10 Except for tobacco smoking, between 1990 and 2010,attributable DALYs of all leading NCD risk factors increased in the Arab world and obesity reached an alarming stage.11In Syria, WHO estimates that NCDs accounted for 46% of total deaths of which 28% are attributed to CVD.12A survey conducted in Aleppo in 2006 involving 1168 adults aged 25 years plus showed a HTN prevalence of 45.6% and 15.6% for DM.13

In the Arab countries, data for NCDs and their risk factors are limited but there is clear evidence that risk factors for the development of NCDs are on the rise. According to WHO, physical activity in the Mediterranean region is very limited and the region ranks the highest for sedentary lifestyle among school-going adolescents (87.5%) and second highest for adults 18y plus (31.1%)9. Low physical activity in the Arab region has been attributed to the lifestyle changes that accompanied urbanisation and the cultural constraints of the conservative communities where women are more likely to stay homd.10 Except for tobacco smoking, between 1990 and 2010,attributable DALYs of all leading NCD risk factors increased in the Arab world and obesity reached an alarming stage.11In Syria, WHO estimates that NCDs accounted for 46% of total deaths of which 28% are attributed to CVD.12A survey conducted in Aleppo in 2006 involving 1168 adults aged 25 years plus showed a HTN prevalence of 45.6% and 15.6% for DM.13

In Lebanon, NCDs are rising rapidly and the gravity of NCDs relates to the prevalence of risk factors as well as proportion of undiagnosed patients. According to WHO, NCDs account for 85% of all deaths in Lebanon of which 47% relate to CVD and 4% to DM.14 A chronic diseases risk factors surveillance conducted in 2008 among a representative population aged 25-64 years old showed that 13.8% of the surveyed population were already diagnosed with HTN and 5.9% affected with DM. Disease prevalence increases with age; for the 55-64y age group, HTN is estimated at 41.6% and DM at 20.3%. Moreover the relatively high percentage of undiagnosed cases is alarming with 12.7% of people having high blood pressure that they did not know about.15 The problem of undiagnosed diseases was also reported in a survey conducted in 2012 -2013 among healthy Lebanese aged 40 years plus where 15% of the respondents had elevated blood pressure and around 10% had elevated random blood sugar.16 The Ministry of Public Health in Lebanon (MOPH) devotes a considerable amount of its budget to subsidise chronic medications that have been distributed free of charge for the last 18 years. In 2012, the MOPH and WHO initiated an NCDs screening programme at primary health care level for early detection and management of HTN and DM cases. Nowadays MOPH/ WHO are joining efforts with various stakeholders for the implementation of a national NCD strategy.

Situation of Syrian refugees in Lebanon

After four years of conflict, bombardments, killing and displacement, the Syrian crisis is turning into a complex protracted humanitarian crisis with millions of displaced people living in poor conditions, facing illnesses and death on a daily basis. In Lebanon, up till June 10th 2015, 1,174,690 Syrian refugees were registered with UNHCR and many more are awaiting registration (suspended since May 6th 2015 as per the Lebanese government directives).17 A vulnerability assessment survey conducted by UNHCR, UNICEF and WFP in 2014 among 1,747 Syrian refugee households showed that despite the continuous assistance provided, the situation of Syrian refugees in Lebanon was deteriorating with half of surveyed respondents below the extreme poverty line for Lebanon (3.84US$/day). Food, rent and health care constitute the main expenditures of 77% of the Syrian refugees. Of surveyed households, 69% benefited from food vouchers and for 41%, these vouchers are the main source of food. Nevertheless the most consumed food groups had low nutrient values and the diversity of food had decreased compared to the previous year.18 Significant variation of diet is associated with the financial status, location and type of shelter and household size.19 Syrian refugees adopted different coping strategies including reduced number of meals and reduced portions, reduced spending on education and health and engaging children in labour.20

For health, more than half of surveyed households articulated a need for greater health support either for chronic diseases or for maternity care. The high cost of health services was noted as the main barrier for management of health problems.21A study conducted in 2013 by Caritas Lebanon Migrant Centre and John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health among 210 older refugees in Lebanon showed that 79% of them did not seek health care because of its high cost and 87% complained of the very high cost of medication.22 Many refugees used to cross the border to get their chronic medication but with the implementation of the legal measures at the border in 2015,this is becoming too difficult.23 For 66% of older Syrian refugees, their health conditions deteriorated in Lebanon and more than half of them report poor health status. 24

Restricted mobility linked to limited legal status constitutes a major source of insecurity, fear and anxiety for the Syrian refugees. By the end of 2013, the Norwegian Refugee Council conducted an assessment among 1,256 Syrian refugees enquiring about the legal component of residency in Lebanon. The survey showed that 89% of respondents exhibited fear of arrest or mistreatment at checkpoints whilst travelling to UNHCR registration sites and trying to access health care services.25

HelpAge project in Lebanon

A survey conducted by HelpAge International (HelpAge) and Handicap International in 2013 among 3,202 Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon showed that 15.6% of the total surveyed population and 54% of older people are affected by at least one chronic disease and that they are facing barriers for proper disease management including difficult access to health care and lack of medications for chronic conditions. Cost was a key element.26 In August 2014, HelpAge launched a health project in Lebanon in partnership with Médecins du Monde (MdM), Amel Association International (AMEL), Young Men’s Christian Association, Lebanon (YMCA) and the American University of Beirut, Centre for Public Health Practice (AUB/CPHP). The project intends to address the major public health issues of Type II DM27 and HTN in the Syrian refugee population and the Lebanese host communities and targets adults from the age of 40. It aims at improving the management of DM and HTN at primary health care level through three pillars: 1) provision of appropriate medical care for HTN and DM, 2) capacity building of local staff with focus on the needs and vulnerability of older adults, and 3) advocacy for specific measures to account for the vulnerabilities of older people in the humanitarian response.

Provision of services

Following a baseline needs assessment and a pilot phase, the project was planned in eight health facilities (five health centres and three mobile units) run by AMEL in four regions in Lebanon that foster underprivileged refugee and host community populations (North Bekaa, West Bekaa, Tyr and Beirut). Pre-project, these facilities were providing basic NCDs care (mostly repeat prescriptions) without active involvement in their proper diagnosis and management. Some of these facilities were dedicated to mother and child care.

At the beginning of the project, the eight health facilities were provided with basic equipment for NCD management at primary health care level(blood pressure machine, stethoscope, weight/height scale, measuring tape, glucometer +lancet +strips), while the health staff received a refresher training on diabetes and hypertension management.

The project offers a comprehensive portfolio of services that cover promotion, prevention and management of DM and HTN. All patients above 40 years of age visiting the health facilities are screened for DM and HTN according to WHO guidelines; people at risk or diagnosed with any of these diseases will receive clinical examination,28 laboratory tests, chronic medications and necessary information about disease management, preventive measures, medication compliance and medical follow up. Information is provided within awareness/informal education sessions.

The clinical assessment is performed by a General Practitioner (GP) and when needed, patients are referred to a specialist -usually a cardiologist. Nominal fees (2000LBP-3000LBP) are paid for this service at the health care centre while it is free of charge in the mobile unit. Medications for chronic conditions are provided free of charge in compliance with the MOPH list for chronic medications and WHO recommendations. Medications are provided either on a monthly basis or quarterly for stable patients, those with disabilities and those aged 60 plus with reduced mobility, in order to minimise transportation issues.

The clinical assessment is performed by a General Practitioner (GP) and when needed, patients are referred to a specialist -usually a cardiologist. Nominal fees (2000LBP-3000LBP) are paid for this service at the health care centre while it is free of charge in the mobile unit. Medications for chronic conditions are provided free of charge in compliance with the MOPH list for chronic medications and WHO recommendations. Medications are provided either on a monthly basis or quarterly for stable patients, those with disabilities and those aged 60 plus with reduced mobility, in order to minimise transportation issues.

Selected laboratory tests, recommended by WHO for the diagnosis and management of DM and HTN, are prescribed at the health facilities (such as HBA1C tests and lipid profiles). To save the patients transportation costs and trouble (especially for disabled and older people), blood samples are collected on site and sent to a nearby laboratory for analysis. Alternatively, patients are directly referred to a laboratory that has a contract with AMEL/ HelpAge. The laboratories do not charge the patients but are reimbursed by AMEL/HelpAge on submission of monthly financial reports. At the mobile units, on-site blood tests for sugar, HBA1C, cholesterol and triglycerides are performed for those unable to reach the clinics.

Patient education is offered in the health centres under three modalities; 1) one-on-one, during the brief time of patient enrolment, 2) brief informal awareness sessions given in the waiting areas, 3) formal sessions scheduled every two weeks (usually 30-45 minutes long), followed by a questions/answers session. In the mobile units, nurses and social workers carry out informal educational and awareness raising sessions to people who gather around the mobile unit whenever the time and workload permits. Patient education and awareness sessions include information about HTN or DM or both. Items discussed include lifestyle modifications (general information on tackling common modifiable factors noted by WHO, such as smoking, alcohol, exercise and diet), and the importance of compliance to medications and follow-up. One to one specific dietary counselling is not provided.

Capacity building

A series of training was conducted throughout the project on different topics as per identified needs. AMEL staff involved in the direct implementation of project services received training on the management of HTN and DM by the Lebanese Cardiology Society and the Lebanese Diabetes Society respectively. The training was followed by one to one training at centres level by the AMEL medical coordinator to foster the implementation of WHO guidelines and ensure quality of care.

Training on drugs use and management was conducted by YMCA to all twenty AMEL centres with on-site follow up and monitoring for the centres included in the project.A training workshop on data collection methods and tools was conducted by the American University of Beirut (AUB/ Centre for Public Health Practice (CPHP) to AMEL staff highlighting the basic principles of evaluative research and data collection with much emphasis on the ethical aspect of data collection, including the concepts of respect, beneficence, social justice and informed consent.Training on accountability was provided by HelpAge to all partners with a focus on the practical application of accountability commitments: participation, transparency, complaint handling and feedback, staff competency, M&E and programme quality.Moreover,AMEL staff were consulted on and involved with the design and planning of activities and the development of monitoring tools and an evaluation plan.At national level, training on the specific needs and vulnerabilities of older adults’ with a focus on HTN and DM was conducted by YMCA for 285 health staff and social workers practicing at primary health care level. Besides the nutritional information and messages about specific dietary measures recommended for diabetic and/or hypertensive patients, training on a mini-nutritional assessment for older people29 was given within the comprehensive geriatric assessment (due to capacity limitations and workload, the mini-nutrition assessment was not implemented in the NCD project).

A specific session on nutritional needs of older people was also conducted in the training. The topics tackled includes nutritional assessment at old age, malnutrition at old age and associated risk factors, symptoms and diseases related to malnutrition at old age, food pyramid for older people, nutritional needs at old age and some tips about nutritional rehabilitation and community support programmes.

Outcomes

Inclusion of older people

This project has proactively supported the understanding and capacity of humanitarian actors to implement older person and disability inclusive humanitarian programming. Older people needs were highlighted on many occasions among humanitarian actors, governmental bodies, United Nations (UN) agencies, international non-governmental organisations (INGOs) and local NGOs.

Enrolment

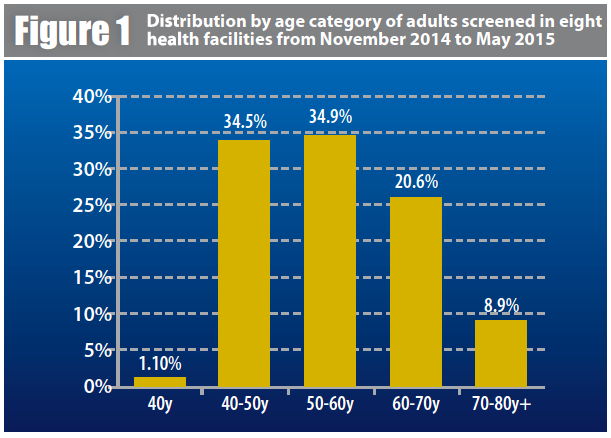

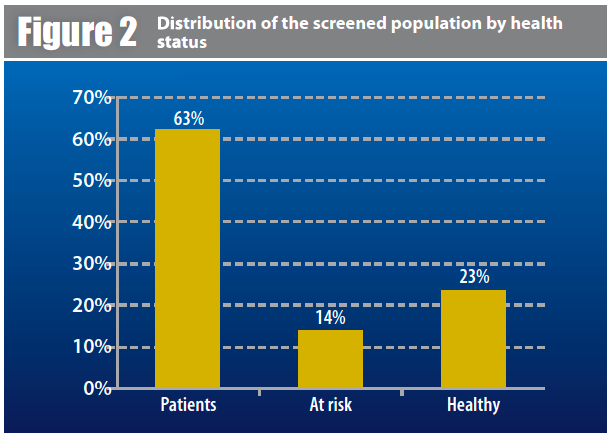

An average of 300 new patients is enrolled every month in the project and 350 patients are followed up every month for the management of their HTN or DM. A total of 2,447 adults aged 40 and above were screened for HTN and DM within a period of seven months of which 67% were females and 33% males (see Figures 1 and 2). From November till end of May 2015, 1,825 patients were enrolled in the programme; 66% were Syrian refugees and 34% vulnerable Lebanese. HTN accounted for 46% of the cases, DM accounted for 27% of the cases and the remaining 27% were affected by both diseases.

In accordance with the disease management schedule, patients receive a medical follow up visit every six months. Between November 2014 and May 2015, 22% of the recruited patients have had two visits, 10% three medical visits and a small number of uncontrolled cases had additional medical follow up.More than 90 awareness sessions about HTN and DM were conducted from December 2014 to May 2015 promoting healthy lifestyle and compliance to the medical treatment. However, only a few patients reported weight reduction and initiation of physical activity following the awareness sessions. Furthermore,both staff and patients had many concerns about the recommended diet since most beneficiaries consumed large amounts of bread (high in salt) and sugar; the main issue was that both the Syrian refugee and vulnerable host community consumed the cheapest type of food rather than the most nutritious or diverse. Diet diversity seemed associated with region, type of shelter and economic situation. Syrian refugees staying at the informal tented settlements in the Bekaa Valley reported high consumption of potato, rice, sugar and tea. Those residing in rented houses in West Bekaa were more likely to eat meat and cereals. Vegetables, fruits and fish were reported of high cost hence not affordable even for the host communities. There was no communication between the NCD programme and the WFP voucher scheme.

Exit interviews conducted among 59 beneficiaries during the month of March showed an overall high patient satisfaction with the programme, especially the opportunity to obtain medications for free, for being given the chance to identify disease through screening, and to be able to access lab tests free of charge. Focus group discussions with the health facilities personnel revealed the overall appreciation of the staff for the project, especially in that it provided the underserved population with a disease screening opportunity and management.

Information about the project was spread in the catchment areas of the involved health facilities including informal tented settlements through flyers and direct contact with key people such as “shawish”, “moukhtar” and municipalities.

Strengths of the programme

The HelpAge project addressed two main problems: lack of access to NCD services and lack of proper management of NCDs.In Syria, refugees were used to benefiting from free health services and regular free drug supply for their NCDs. In Lebanon, only poor people and older adults benefit from free drugs for NCDs, and only in selected facilities supported by the YMCA. Within the response to the Syria crisis, the Instrument for Stability Project funded by the European Union enabled distribution of chronic medication to 150,000 patients in 435 primary health facilities; however, shortage in chronic medication was still noted.30

The HelpAge project allowed more vulnerable older adults to benefit from free services.The programme was tailored according to the needs of the target population; for example blood sampling was done on site since transportation is problematic (in terms of security, availability and affordability).High levels of satisfaction and a sense of ownership was reported by AMEL staff who appreciated the positive work dynamics among all members and the efforts to make the best out of delivering the service.

The programme was very effective from a partnership perspective. It embraced five partners that interact and cooperate to attain the project objectives. From the early stage of the project design, all partners were consulted on how to design the intervention in a way to ensure complementarity, quality and sustainability of services; each partner brought its expertise and speciality into the project and efforts were geared to support and complement each other. Furthermore the training on older adults’ specific needs and vulnerabilities is a pioneer initiative acknowledged by all participants.

For the Lebanese population, the government provides medication for chronic conditions but only within the MOPH network that includes almost one-quarter of the primary health care facilities31. For the Syrian population, there is a project that enables them to access such medications in the MOPH network when certain conditions are met. HelpAge is planning to continue this programme for the next 30 months while building the capacity of AMEL centres to join the MOPH network to ensure access to patients and sustainability of services.

Challenges

The major constraint has been insecurity. The initial design of the project included an AMEL health facility in Ersal. However, following security incidents occurring in the early phase of the project, generating temporary suspension of humanitarian operations, the decision was made to provide in kind support (equipment and medication) rather than implementing the full package of services. The kidnapping of Lebanese soldiers in North Bekaa in September 2014 resulted in road blockades for 17 days and an overall period of no security clearance for 6-7 weeks, which delayed the health facilities assessment and the refresher training on WHO guidelines. Other security events affected the mobility of the refugees, i.e. the one day mobilisation campaign in Mashghara coincided with a military incident, leading to checkpoints being spread all over the region, preventing even the host community from going out. Consequently despite a well disseminated message about the campaign and thorough organisation of the event, the number of beneficiaries was relatively low and only three Syrian refugees were able to attend.Furthermore, the fluid movement of the refugee population according to the level of security made it difficult to accurately assess and meet the needs of this population, e.g. following refugee influxes, there might be greater demand for medications than planned.

It was important and challenging to align the approaches, have clear communication channels and consensus on roles and responsibilities of the five agencies involved in the programme.

It was important and challenging to align the approaches, have clear communication channels and consensus on roles and responsibilities of the five agencies involved in the programme.

Resistance to changes in practice was evident amongst some service delivery staff so a key element was to highlight the importance of the project and to trigger a sense of ownership through active involvement in the project activities. At the same time, close monitoring was critical to allow intervention as necessary.

From a beneficiary perspective, the main obstacle to visiting a health facility is transportation; transportation fees may add up to 15,000LBP (=10US$) which is considered expensive by both Syrian refugees and vulnerable host communities. Consequently, the services provided by the mobile units are considered “as a gift from heavens”. Waiting time at the health facility is another problem for beneficiaries, especially for the frail and older patients. Waiting times become a major obstacle at mobile units during harsh weather conditions as it is difficult for the patients to be standing outside in cold or excessively hot weather waiting to be screened or managed.Opening hours of the centres is another issue with most closing at 2 pm, making it difficult for people among the local host communities and a small number of refugees who work during the day. This might explain the high percentage of women compared to men.Shortage of medication is a major concern for patients who may not get all prescribed medication on the same visit. This relates to the high consumption of drugs associated with the increased number of beneficiaries. A contingency stock was established at AMEL headquarter to address this issue but delayed reporting of need and insufficient means of transportation created delay in the delivery of medication.

Health care providers state that the length of time it takes to perform all the required tasks as per the guidelines and the increased workload make services provision difficult and challenging. The screening process is viewed by the health staff as successful but highly stressful because of the high volume of patients and the requirement of a10-15 minutes consultation to collect data and indicators as per WHO guidelines. The consequences are longer waiting times for other patients to be screened and more congestion in the centres.

The increased workload is affected by a number of determinants such as 1) the security situation,e.g. when Syrian refugees fled from North to West Bekaa following military actions, the influx of patients necessitated the recruitment of additional staff to cover the additional work, 2) the shortfall in international humanitarian response funding resulted in closure of services; in February 2015, International Organisation for Migration (IOM) had to shut down services in two clinics in the Bekaa area resulting in an influx of patients to AMEL centre in Kamed El Loz; 3) the deteriorating economic situation for both Syrian refugees and host communities resulting in an increase in the number of vulnerable people requiring health services.

Key lessons learned

Essential basic equipment for the management of DM and HTN at primary health care level can be modest and affordable, however the capacity of the health staff and their skills in the management of HTN and DM are critical for the proper management of the diseases.Educational background, training and capacity building of staff are essential elements for the success of similar projects.

Flexibility in the implementation of guidelines and tailoring of activities as per resources and needs of the beneficiaries is vital; the guidelines needs to be adapted to the context and not adopted as they are. For example, laboratory tests implemented in the primary health care centres could not be implemented at the mobile clinics because of transportation strains.

Resistance to change, especially among older experienced staff, might be problematic and it is challenging to trigger the interest of such staff and generate a sense of commitment to the project.

Time is a key factor; in an emergency context especially, there may be major delays in activities due to insecure situations. Contingency planning is important in such contexts.

The success of partnership requires sound coordination and a number of key elements such as involvement of all partners in all stages of the project development and implementation to ensure that decisions and activities receive widespread support and recognition; clear communication of responsibilities and perceived roles to avoid misunderstandings, frustration and loss of commitment; and sharing of information continuously and in a timely manner. Trust takes time to be built between partners but it is the basis of a strong and sustainable partnership.

Conclusions

NCDs management should be seen as a fundamental pillar of the long-term policy response to the crisis in Syria. The HelpAge health project is a successful example of a comprehensive package of services and collaboration among different partners. Similar projects should be encouraged and scaled up to meet the increasing health needs of Syrian refugee and host communities.

For more information, contact: Maguy Ghanem, email: maguy.ghanem@helpage.org

1Bloom DE, Cafiero ET, Jane-Llopis E, Abrahams-Gessel S, Bloom LR, et al (2011). The global economic burden of non-communicable diseases.Geneva:World Economic Forum. p48

2World Health Organisation (2011). Global status report on non-communicable diseases 2010. Geneva

3P. M. Kearney, M. Whelton, K. Reynolds, P. Muntner, P. K.Whelton, and J. He, “Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data,” The Lancet, vol. 365, no. 9455, pp. 217–223, 2005

4N. Unwin, D. Whiting, L. Guariguata, G. Ghyoot, and D. Gan, Eds., Diabetes Atlas, International Diabetes Federation, Brussels, Belgium, 5th edition, 2011

5Global Burden of Disease 2004 Update (published 2008) http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GBD_report_2004update_full.pdf

6see footnote 2

7see footnote 2

8see footnote 2

9RWHO- Global Health Observatory Data Repository, Prevalence of insufficient physical at http://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main.2482?lang=en

10Abdul Rahim, H., Sibai,A., Khader, Y., Hwalla, N., Fadhil, I., Al Siyabi, H., Mataria, A., Mendis, S., Mokdad, A., Husseini, A., 2014, Non-Communicable Diseases in the Arab World, Lancet, 383: 356-367

11See footnote 10

12World Health Organisation-Non Communicable Diseases ( NCD) Country Profiles, 2014 Syrian Arab Republic 7

13Radwan Al Ali, R., Rastam, S., Fouad, F., Mzayek, F., Maziak., W, 2011, “Modifiable Cardiovascular Risk Factors Among Adults in Aleppo, Syria” International Journal of Public Health, 56 (1) 8

14WHO, Non communicable diseases profile Lebanon, 2014

15RSibai AM and Hwalla N. WHO STEPS Chronic Disease Risk Factor Surveillance: Data Book for Lebanon, 2009. American University of Beirut, 2010 (http://www.moph.gov.lb/Publications/Documents/WHO_Databook_Lebanon_2010_final.pdf).

16Yamout, R., Adib, S., Hamadeh, R., Freidi, A., Ammar, W., 2014, Screening for cardiovascular Risk in Asymptomatic Users of the Primary Health Care Network in Lebanon, 2012-2013, Preventive Chronic Diseases, 11: 140089

17href="http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/country.php?id=122">http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/country.php?id=122 accessed June 23rd 2015

18Syrian Refugee Response: Vulnerability Assessment of the Syrian Refugees in Lebanon 2014

19Jonathan Strong, Christopher Varady, Najla Chahda, Shannon Doocy, Gilbert Burnham. 2015. Health status and health needs of older refugees from Syria in Lebanon. Conflict and Health 9:12 doi:10.1186/s13031-014-0029-y 14. See also footnote 18.

20See footnote 18

21See footnote 18

22See footnote 19

23See footnote 19

24See footnote 19

25The Consequences of Limited Legal Status for Syrian Refugees in Lebanon, NRC Lebanon Field Assessment: North, Bekaa, South, March 2014

26Hidden victims of the Syrian crises: disabled, injured and older refugees copyright 2014 HelpAge International and Handicap International& UNHCR 2014. Health access and utilisation survey among non-camp Syrian refugees. Available at http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/download.php?id=6029

27RInsulin dependent (Type I) diabetes is not managed within this project.

28This included Body Mass Index (BMI) and waist circumference to assess risk of disease.

29This involved a screening tool that captures anthropometry (BMI, MUAC), weight loss history, social factors, mobility, psychosocial and dietary characteristics to generate a malnutrition risk score.

30Reducing conflict by improving healthcare services to vulnerable Lebanese and Syrian Refugees.Lebanon Update.3 July 2015.

31National Health Statistics Report in Lebanon, 2012 edition