Contributing to the Infant and Young Child Feeding in Emergencies (IYCF-E) response in the Philippines: a local NGO perspective

By Romelei Camiling-Alfonso, Donna Isabel S. Capili, Katherine Ann V. Reyes, A.M. Francesca Tatad and Maria Asuncion Silvestre

Romelei Camiling-Alfonso has worked for the Department of Health, Philippines as rural health physician prior to involvement in public health initiatives on maternal and child health. She participated in IYCF-E efforts post-Bopha and was a representative to the Nutrition Cluster IYCF technical working group (TWG) through Kalusugan ng Mag-Ina (Health of Mother and Child), Inc (KMI).

Romelei Camiling-Alfonso has worked for the Department of Health, Philippines as rural health physician prior to involvement in public health initiatives on maternal and child health. She participated in IYCF-E efforts post-Bopha and was a representative to the Nutrition Cluster IYCF technical working group (TWG) through Kalusugan ng Mag-Ina (Health of Mother and Child), Inc (KMI).

Donna Isabel S. Capili is a consultant on Maternal and Newborn Health, KMI. She is a neonatologist, working in public health and actively involved in the Essential Intrapartum and Newborn Care Programme. She acted as manager and a breastfeeding counsellor of the WICS - Nanay Bayanihan tent in Villamor Airbase for arriving Haiyan survivors, and was part of the KMI team represented at the National Nutrition Cluster TWG.

Donna Isabel S. Capili is a consultant on Maternal and Newborn Health, KMI. She is a neonatologist, working in public health and actively involved in the Essential Intrapartum and Newborn Care Programme. She acted as manager and a breastfeeding counsellor of the WICS - Nanay Bayanihan tent in Villamor Airbase for arriving Haiyan survivors, and was part of the KMI team represented at the National Nutrition Cluster TWG.

Katherine Ann V. Reyes, MD, MPP is a public health practitioner with background in health policy, health service development, and research, particularly regarding maternal and child health issues. She is Executive Director and founding member of the Alliance for Improving Health Outcomes, Inc, an NGO that supports health sector partners. She has previously worked with DOH, PhilHealth, WHO, Kalusugan ng Mag-Ina, Inc, USAID and MeTA among others.

Katherine Ann V. Reyes, MD, MPP is a public health practitioner with background in health policy, health service development, and research, particularly regarding maternal and child health issues. She is Executive Director and founding member of the Alliance for Improving Health Outcomes, Inc, an NGO that supports health sector partners. She has previously worked with DOH, PhilHealth, WHO, Kalusugan ng Mag-Ina, Inc, USAID and MeTA among others.

A.M. Francesca Tatad is a neonatologist, member and co-convenor of KMI, and founding member and medical advisor of LATCH, Inc (Lactation, Training, Attachment, Counselling and Help), an NGO that promotes and supports breastfeeding through training, counselling and advocacy.

A.M. Francesca Tatad is a neonatologist, member and co-convenor of KMI, and founding member and medical advisor of LATCH, Inc (Lactation, Training, Attachment, Counselling and Help), an NGO that promotes and supports breastfeeding through training, counselling and advocacy.

Maria Asuncion Silvestre is a neonatal and perinatal medicine specialist. She is a consultant for Early Essential Newborn Care and Breastfeeding, WHO Western Pacific Regional Office. The Founder and President of Kalusugan ng Mag-Ina (Health of Mother and Child), Inc., (KMI), she actively participated in delivering on KMI IYCF-E efforts in the Post-Haiyan response.

Maria Asuncion Silvestre is a neonatal and perinatal medicine specialist. She is a consultant for Early Essential Newborn Care and Breastfeeding, WHO Western Pacific Regional Office. The Founder and President of Kalusugan ng Mag-Ina (Health of Mother and Child), Inc., (KMI), she actively participated in delivering on KMI IYCF-E efforts in the Post-Haiyan response.

The authors wish to extend thanks to many individuals that are too numerous to mention here but include Nanay Bayanihan co-convenors Atty. Jenny Ong and others involved in LATCH and the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas; mother support groups in the cities of Cagayan de Oro, Davao and Cebu; Breastfeeding Pinays and Arugaan; the Alagang Kapatid Foundation in Metro Manila; doctors who spearheaded the Busuanga Mission; and Dr Paul Zambrano for engaging with KMI in Compostela Valley. Thanks also to Dr Anthony Calibo of the Family Health Office, DOH, for facilitating networks within the sector; Ms Flor Panlilio of the Health Emergency Management Bureau, DOH; the National Nutrition Council; the Regional Health Office National Capital Region for engaging LGU-trained breastfeeding groups for counselling; Dr Cristina Cornelio and the Breastfeeding Committee of the Philippine Pediatric Society; and individual PPS volunteers. We also thank the Philippine Air Force Officers' Ladies Club for giving us the space; the numerous individual volunteers for their time and resources; RMD Kwikform for providing the tent at Villamor Airbase; the human milk banks; and hospitals that enabled breastmilk donations. Most importantly, we thank the many breastfeeding mothers and their babies for their selfless “gifts of human kindness”, whether bestowed through wet nursing or through human milk banks.

Location: Philippines

What we know: The Philippines is prone to natural disasters. Recent emergencies have challenged meeting the needs of both breastfed and non-breastfed infants. National capacity and reactivity is critical to early frontline support in acute onset emergencies.

What this article adds: In response to Typhoon Haiyan (2013), an existing national NGO (Health of Mother and Child) mobilised an informal but wide network of experienced volunteers to support national IYCF-E efforts. Primary activity was frontline support to breastfeeding mothers in reception centres, development of Women and Infant Child Friendly Spaces (WICS) and advocacy and action regarding donations of breastmilk substitutes. Social media was heavily used. Pasteurised breastmilk was coordinated and successfully delivered via cold chain to targeted infants. Limited capacity and resources mean impact data is lacking; however insightful models of action through case studies are provided. The authors flag that support to non-breastfed infants (20% of under 1’s in one assessment) was a significant gap in both the national and international led response.

The Philippine archipelago is prone to natural disasters; hydrological events alone average to 25 tropical cyclones a year. A quarter of our population lives below the poverty line, and a recent series of both natural and man-made emergencies has amplified weaknesses in our disaster response. With climate change, mega-disaster scenarios similar to Typhoon Haiyan (local name Yolanda, 2013) should be anticipated here and in other countries.

With lessons learned from volunteer work during typhoons Ketsana/Ondoy (2009) and Bopha/Pablo (2012), our non-governmental organisation (NGO) Kalusugan ng Mag-Ina (Health of Mother and Child), Inc. participated in post-Haiyan nutrition responses. KMI is a non-stock, not-for-profit NGO working to promote and protect the health of the mother-child dyad through research, policy development, and programme implementation. We convened a network of volunteers, acted as an implementing partner for international NGOs (INGOs), and later contributed technical support to the national nutrition response through participation in the National Nutrition Cluster Technical Working Group (TWG). This article focuses on interventions for infants and young children in emergencies and learning and recommendations are highlighted.

Infant and young child feeding: the Philippine context

In 1986, the Philippine Milk Code (Executive Order 51) was legislated. Among other things, it prohibits donations of infant formula, breastmilk substitutes, feeding bottles, artificial nipples and teats during emergencies. The law bans indiscriminate distribution of these products as they put infants at greater risk of illness and death.12 Implementation of the law is poor at best. Local governments lack applicable operational guidelines for implementation of IYCF in emergencies. Messaging is often limited to promoting breastfeeding and limiting formula milk donations; poor understanding by the general public leads to the perception that the law is harsh and irrelevant. Post-Haiyan, this created a barrier to service delivery such that there was palpable pressure from multiple sectors to allow formula donations.

Toddler formula is widely marketed in the Philippines, being incorrectly perceived as exempt from Milk Code restrictions and a necessity both by health care providers and the general public. Well-meaning souls donate toddler milk assuming that it will be fed only to toddlers, not realising that mothers in low-resource settings will give any available milk to their young infants whether toddler milk or even coffee creamer. Diluted preparation of milk powder is common to make the powder last longer, contributing to both acute and chronic malnutrition. This puts infants at even greater danger post-disaster when clean water is not available, bottles cannot be cleaned, and congestion and lack of toilet facilities in evacuation centres make for extremely harsh environments.

In the Philippines, only 34% of infants under 6 months are exclusively breastfed. Also, only 34% continue to breastfeed until two years of age.3

The Philippine health system

To understand the challenges of implementing an effective emergency IYCF response, it is important to understand the structure of the Philippine health system. In 1992, the Philippines devolved the management and delivery of primary health services from the central Department of Health (DOH) to locally elected provincial, city and municipal governments in order to allow mid-level managers greater autonomy in decision-making, facilitate resource allocation based on local priorities and improve the management of local health services.4

The DOH maintains its leadership through health policies, technical assistance and regulation, with its regional health offices providing guidance to local government units. However, the implementation of DOH policies across the islands is variable, depending on each local government unit’s independent commitment to health. At the city/municipal level, primary health care services, such as breastfeeding and nutrition interventions, are delivered through Health Offices’ midwives that supervise barangay (village) health stations. Not unusually, one midwife may be in charge of several villages. There is also a designated Nutrition Officer per locality, which may or may not be part of the Health Office. Midwives heavily rely on barangay health workers (BHW), community volunteers often chosen for their leadership potential or/and political affiliations. Volunteers who assist specifically with nutrition services are called barangay nutrition scholars (BNS).

The integrity of the health care delivery system is vulnerable to large scale catastrophic events where even local health workers become victims. Rescue workers are often unfamiliar with local policies so NGOs like ours address this by providing technical assistance to meet immediate needs and assist in capacity rebuilding thereafter. Much of KMI’s work post-typhoon Haiyan focused on IYCF interventions at local or grassroots levels.

IYCF interventions in local or grassroots disaster responses: anecdotes

Nanay Bayanihan: A Woman, Infant and Child (WIC) or Mother-Baby Friendly Space

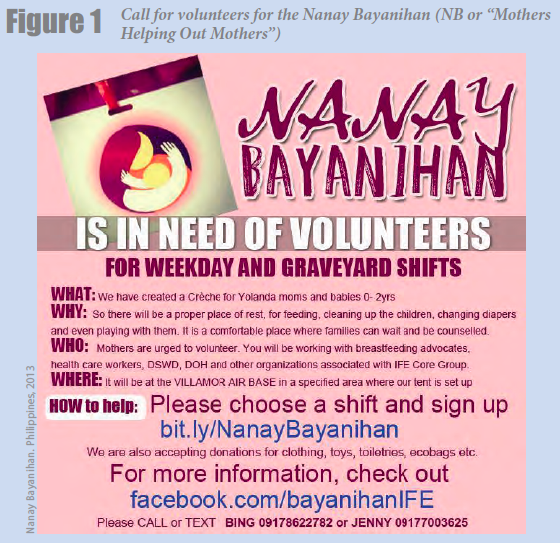

At about seven days post-landfall, we received a distress call from volunteers at the Villamor Airbase, the transit area for typhoon survivors who had been airlifted from Eastern Visayas to Metro Manila. “Mothers with small infants are being handed bottles with milk powder as they deplane! What should we do?” We contacted the relief organisers and briefed them on the importance of a Woman, Infant and Child (WIC) friendly space where mothers could support, protect and promote IYCF-E. Camp management then designated a WIC space, which was prepared, operated and promoted through word of mouth and social media. Volunteers from both private and public sectors converged and became known as Nanay Bayanihan (NB or “Mothers Helping Out Mothers”). What started out as woven mats laid out over cardboard sheets under a tree evolved into a modular steel framed shelter generously built by a private donor. The area served as a haven to weary and hungry mothers and children.

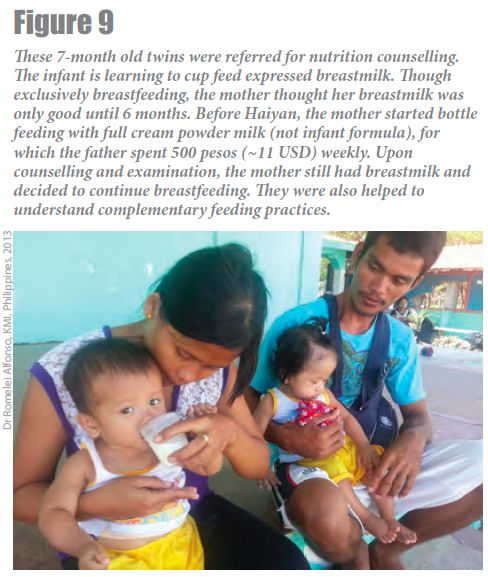

Over November 15-21, 98 children aged 0 to 5 years were referred to us. In the first 48 hours or so of our operations, marshals were not yet systematically directing all mothers with young infants and children to our tent yet. As such, this total of 98 reflects only those that arrived at our NB tent. Among those 0-6 months of age, 83.3% were breastfeeding (42.9% were exclusively breastfeeding, 40.4% were supplementing with infant formula). Among all infants 0-1 year of age, 79.9% were breastfeeding.

The NB WIC space was staffed by volunteers including lay personnel, breastfeeding mothers, peer counsellors, and health professionals, 24 hours a day. NB tent managers conducted daily orientation with materials made available via the group’s Facebook account.5 Each incoming flight was met by camp marshals who screened the arrivals for families with infants and young children. Families were registered at the social welfare desk then invited to the NB WIC space, with knowledge of their case worker. Mothers and their children were encouraged to rest and given warm food and water, hygiene materials and clothing. Oral vitamin A was administered. Trained counsellors and health professionals inquired about the mothers’ feeding practices from before and after Haiyan, and provided support, counselling and affirmation to those already breastfeeding. Counselling tools on infant and complementary feeding developed by the DOH-National Nutrition Council (NNC) were utilised for non-breastfed infants who were predominately fed infant formula. Volunteer wet nurses shared personal insights with fellow mothers, particularly those struggling with breastfeeding. Whenever feasible, mothers were referred to an IYCF counsellor at their final destination. Given our limited capacity, it was not possible to systematically gather quantitative data.

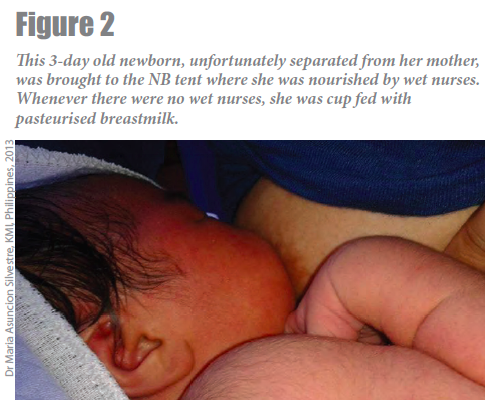

The Cold Chain Project

Although not a primary strategy, the provision of pasteurised donor breastmilk proved helpful in the absence of mechanisms to address non-breastfed babies’ needs. Donor breastmilk on standby weakened this loophole in our promotion of IYCF-E practices. Volunteers attended to mothers whose breastfeeding had been disrupted. NB reinvigorated a campaign for donor human milk. The response from donors and from milk banks at the Dr. Jose Fabella Memorial Hospital, Philippine General Hospital, and Philippine Children’s Medical Centre was overwhelming. When volunteer wet nurses were not available, the pasteurised donor milk was cup-fed to priority recipients, e.g. orphans, sick infants, or hungry infants whose mothers needed relactation support. Due to limited capacity with staff stretched to their limits in the response, it was not feasible to gather data systematically.

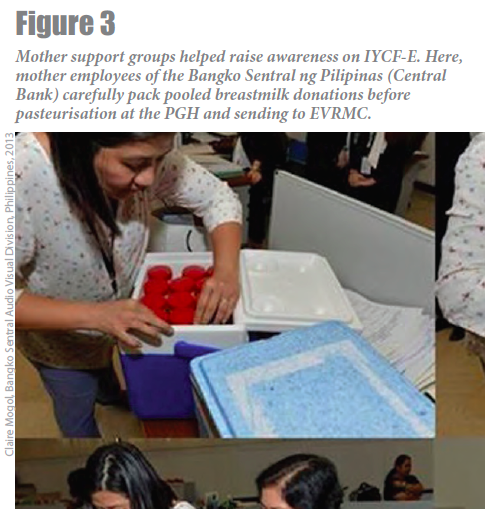

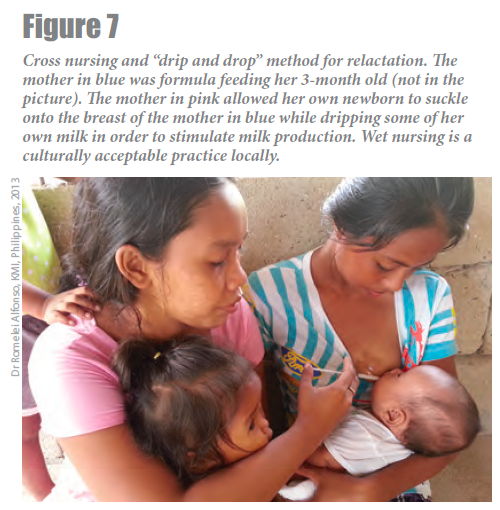

Donor breastmilk was also airlifted on military planes for 40 infants, some preterm babies in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) but mostly older diarrhoeic infants at the Eastern Visayas Medical Centre (EVRMC) in Tacloban which had made an urgent call for donor milk. Through the network of individuals and organisations, a generator was procured and sent to EVRMC. The need for donor breastmilk was addressed through multiple agencies (Armed Forces of the Philippines, DOH, NGOs, hospitals). It was feasible to collect, transport and store pasteurised breastmilk in a cold chain meeting the requirements of survivors without needing to solicit formula donations. In the transit areas, where mother-infant dyads’ stay was short term, the pasteurised donor milk was used for any young infant that needed to be fed acutely (whether exclusively breastfeeding, exclusively formula feeding or mixed feeding), after consent, via cup feeding. It was also used for the mothers who needed to be relactated using drip drop and cross nursing techniques. In the recipient hospital in Tacloban (EVRMC), the pasteurized donor milk (requested by the hospital chief) was fed via tube or cup feeding to mostly older formula feeding infants being treated for gastroenteritis in their paediatric wards. We also highlighted the shortage of breastmilk in referral hospitals, and the existence of mother support groups.

Monitoring of ‘Milk Code’ violations

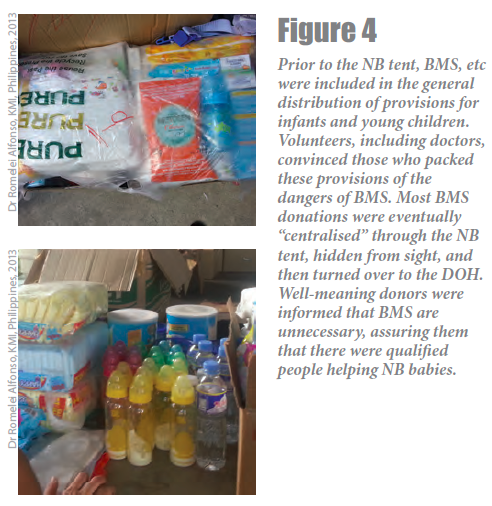

The NB tent became known as the babies’ and children’s tent, and as such the default recipient for food and clothing donations but also unsolicited powdered milk and feeding bottle donations. Donors who brought in breast milk substitutes (BMS) and feeding implements were diplomatically informed on why these were not helpful and that the items would be turned over to the DOH NCR office for inspection and disposition. NB convenors granted interviews to trimedia journalists and reporters who flocked to the NB tent, always emphasising breastfeeding protection and the dangers of BMS.

The Busuanga experience

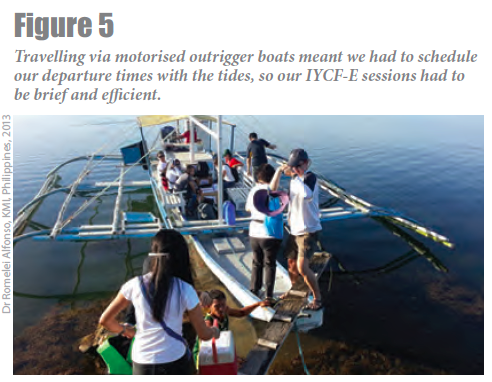

While most relief and media attention was focused on the Visayas, nine days post-first landfall, we participated in a “medical mission” to Busuanga, a site of Yolanda’s sixth and last landfall, where no medical groups had been deployed before. With 2 surgeons, 1 obstetrician and 3 other doctors, 2 nurses and a pharmacist, we conducted the IYCF-E efforts, bringing cups, syringes and pasteurised donor milk along with medical supplies. We first networked with their municipal health officer and his wife, a nutritionist. Because we were to travel by small boats between islands, we arranged to leave most of our back-up donor milk in the health unit’s vaccine freezer and transport aliquots of milk with us in coolers. At our base island, we bought out all the available vegetables for distribution to families with older children. We worked with the nutritionist and the “barangay nutrition scholars” to ensure sustainability, doing individualised feeding assessments and demonstrating methods to support relactation, i.e. the drip-drop method, tandem nursing, cup and syringe feeding, hand expression and proper storage of breastmilk. We counselled them on appropriate complementary feeding, handed out vegetables, and advised them to plant the seeds.

Nutrition interventions in the National Disaster Response

The National Nutrition Cluster led by the DOH-NNC and UNICEF, is activated during times of emergencies. There are four technical working groups: Assessment and Monitoring, Advocacy and Communications, Community Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM), and IYCF-E. Post-Haiyan, nutrition cluster counterparts were activated simultaneously in three regions. Sub-regional coordination hubs were further activated. As was the general experience among different clusters, coordinating these bodies proved challenging due to the unprecedented magnitude of destruction, as well as human resource limitations.

The government released its strategic plan, Reconstruction Assistance on Yolanda (RAY), to provide overall guidance for implementation of recovery and reconstruction programmes in Post-Haiyan areas. There was no recommendation specific to nutrition6 until Day 41, when the final report indicated under-five malnutrition prevalence as a health outcome to be monitored.7 Among 126 teams deployed by the DOH Health Emergency Management Bureau (HEMB) within the month following landfall, only one had a specific nutrition function.8Because local health workers were victims themselves, few could return to work quickly. Nutrition interventions (e.g. Rapid Nutrition Assessment, IYCF and breastfeeding support) were performed mainly by dedicated staff of NNC and partners deployed by the Nutrition Cluster.

During the rehabilitation phase, health care providers from barangay to municipal levels underwent various training activities from the different clusters. Implementing partners had to complete all activities before funds expire, often resulting in simultaneous trainings and competition for participants. In our experience as implementing project partners, local health officers expressed appreciation for trainings but also, their difficulty to absorb everything and compromises they had to make in order to attend. At some point, local executives requested minimisation of out-of-office days of local health staff, as service delivery was compromised in their absence.9

Rethinking intervention strategies

As an active partner of the NNC, we emphasised the following:

Operationalising IYCF-E in WIC Spaces as Mother-Baby Friendly Spaces

With an unprecedented 13 million people displaced, the capacity of local and national support systems to provide food, water and shelter was overwhelmed post-Haiyan. The need for WIC spaces was sorely felt in heavily congested evacuation centres. We recommend the early delineation of women and child-friendly spaces following the initial census taking. Specific steps towards integrating services for women and children can then be outlined to allow for their expedited and efficient delivery, and for monitoring indicators. Mothers of young children should not have to queue up for food and water supplies. While Department of Social Welfare and Development’s Camp Management Guidelines call for a WIC space, services are yet to be harmonized with IYCF-E strategies. The capacity of international coordinating staff on IYCF-E is also variable. The implementation of mother-baby friendly spaces, if any, still lacks functionality standards. For example, during Haiyan, one of the tents put up by an implementing partner was nicely constructed but utilisation was poor. One frontline responder observed it was too hot inside.

As such, we recommend standardisation of recommendations between the Health and Social Services Departments.

Health and nutrition services for pregnant women and their newborns are part of a continuum. A survey conducted in affected areas after the typhoon reveals that an alarming 14% of infants aged 0-23 months were never breastfed.10 The design of the survey captured infants born before, during and after typhoon Haiyan. This reflects a gap in basic maternal and newborn care. Furthermore, essential birthing services were unavailable until much later when tents and mobile vans were set up to provide obstetric services. Safe births and breastfeeding initiation rates could have been increased by creating WIC spaces with basic birthing supplies should transport to a health facility not be feasible just yet.

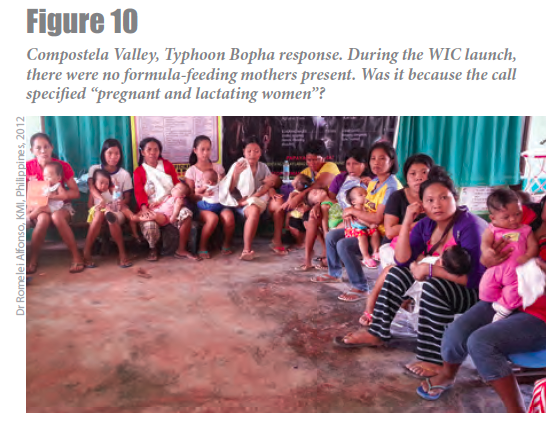

In implementing WICs, frontline staff should be careful in communicating about their target groups. Bottle-feeding mothers may be inadvertently excluded because “calls” are addressed to “Pregnant and Lactating Mothers”. Aiming to report official numbers of this high-risk group is critical nevertheless, formula-fed children can be “systematically” excluded from counting, especially when families have already left evacuation centres, effectively marginalising this high-risk group even more.

Reengineering capacity buildling

Essential competencies to IYCF-E implementers include skills in hand expression of breastmilk, alternative feeding methods such as cup feeding, relactation, and knowledge on the sourcing and preparation of appropriate complementary foods. Successful IYCF-E cannot be limited to counselling on exclusive breastfeeding and complementary feeding as the needs of non-breastfed and mixed-fed infants demand attention. The ideal IYCF-E response should be widespread and coordinated rather than dependent on a few local experts working reactively.

IYCF practices should be robust so that exclusive breastfeeding and appropriate complementary feeding are “pre-positioned” proactively. KMI promoted integration of IYCF-E in “normal” programming through the standard Essential Intrapartum and Newborn Care (EINC) or First Embrace 11. This notably included, training for 42 priority municipalities in the Haiyan corridor and in major medical, midwifery and nursing schools, and end-referral hospitals nationwide.

Responding with sensititivey to local context and cultures

While regulation of BMS is important post-disaster, this is easier said than done. It is difficult for health managers and the general public to fully appreciate the risks of formula feeding and to discourage or not distribute untargeted BMS supplies, if safeguards and systems of support are not in place for babies who do not breastfeed. In the absence of clear frameworks and safeguards, as was the case in this humanitarian response, “regulating” people often works only to burn bridges.

Social media and strong leadership from existing mother support groups e.g. LATCH and Breastfeeding Pinays, facilitated the convergence of volunteer mother support groups, a valuable resource for the government during times of disaster. There must be a mechanism for nurturing, sustaining and recognising their contributions to augment local health workers and government responders.

Reflections of a national organisation

The efforts reflected in this article were exerted by a lean organisation comprised of a network of committed volunteers, coordinated by at most six people – again volunteers - at a given time. Much of the activities we undertook were to fill locally unrecognised gaps in support of the national efforts and human resources spread out really thinly at that time. Our attempts to secure funding for relief efforts (related to WIC and “breastfeeding missions”) at the height of response were unsuccessful due to many constraints, including the manpower needed to develop proposals and solicit support. We subsequently secured funding from UNICEF in the rehabilitation phase to strengthen and capacitate birthing facilities in 42 municipalities. In the latter capacitation project, we incorporated an IYCF-E module targeting health officers and midwives.

Although we tried, we have little data to support our experiences in terms of numbers, coverage, and impact of the interventions. Our working in a very limited setting with capacity constraints, permitted showing models for action but not data on impact. We have worked in transit areas and there was no feasible way to track the outcomes. Our visits to communities were brief.

Through our work, we observed systems gaps that we feel are important to mention. In the Haiyan response, there were no specific actions for non-breastfed babies. Their needs must be met acutely to reduce “tension” but in ways that comply with the Milk Code by exhausting safer viable options like relactation, wet nursing and provision of donor milk as mainstream interventions. Otherwise, in the absence of official channels of support, families will source out BMS donations elsewhere, as observed in this crisis.

Cebu experience

We received an appeal for breastmilk on social media from a paediatrician in Cebu City, the largest transit area post-Haiyan. We thus airlifted pasteurized donor milk from Manila to the military hospital there. Donor milk was stored in BPA-free cups so it could be fed to recipients after thawing. The milk was directed to priority recipients at the Cebu hospitals and at the EVRMC in Tacloban. We delivered a donated freezer to the Cebu Provincial Hospital, the referral hospital for hardest hit municipalities in Northern Cebu. Being an MBFHI (Mother and Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative) hospital with high exclusive breastfeeding rates, the staff declined the donor milk. They had also confiscated and surrendered formula donations from a foreign medical group. We also visited a Cebu City orphanage and evacuation centre, and at the latter, met with social worker camp managers, educated them on IYCF-E and mother-baby friendly spaces.

An important gap: IYCF-E operational guidelines

Frontline health workers asked, “now that BMS donations are prohibited, what will I do with infants already formula feeding before the disaster?” This provoked heated discussions among donors, health workers and lay volunteers, many of whom lacked practical skills in breastfeeding counselling and support for complementary feeding. Hence, drafting of the national IYCF-E operational guidelines became one of the priorities of the National Nutrition Cluster. At the time of writing this article, the draft operational guidelines await review approval from the DOH.

The draft outlines ways of managing formula donations: return to donor, reusing ‘suitable’ milk (e.g. by pre-mixing with fortified blended food for blanket supplementary feeding, institutional support for other vulnerable groups, animal feeds, as ingredient for other foods that can be distributed), and destruction of ‘unsuitable’ products.

It was recommended that only qualified health/nutrition workers trained in breastfeeding counselling and infant feeding dispense formula to caregivers, after safer alternatives have been explored and formula feeding risks have been discussed with carers. Procurement and distribution of formula should only be a last resort, through responsible Regional Health Offices, and regulated according to set standards.

Conclusion

Though perceived as the most vulnerable, the exclusively breastfed infant is the most food-secure post-disaster. While IYCF-E and nutrition initiatives mention breastfeeding in policy and strategy frameworks, there is lack of direct interventions and capacity building for practical skills for its protection, promotion and support. Robust IYCF practices should be “pre-positioned” so that impact of post-disaster IYCF-E responses can be maximised. Our post-Haiyan experiences at the grassroots level supplied proof of concept activities that can be models for programming and implementation of national emergency responses.

For more information, contact Lei Alfonso, email: rcalfonsomd@gmail.com

1Adhisivam B, et.al. Feeding of infants and children in tsunami affected villages in Pondicherry. Indian Pediatr. 2006 Aug;43(8):724-7.

2Hipgrave DB, et.al. Donated breast milk substitutes and incidence of diarrhoea among infants and children after the May 2006 earthquake in Yogyakarta and Central Java. Public Health Nutrition. 2012 Feb;15(2):307-15

3The State of the World’s Children, UNICEF, 2014.

4Overview of devolution of health services in the Philippines. Rural Remote Health. 2003 Jul-Sep; 3(2):220.

5https://www.facebook.com/bayanihanIFE

6National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA), 2013. Reconstruction Assistance on Yolanda (RAY): Build Back Better. Manila. (http://www.gov.ph/downloads/2013/12dec/20131216-RAY.pdf)

7NEDA, 2013. Reconstruction Assistance on Yolanda (RAY): Implementation for Results. Manila. (http://www.neda.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/ray_ver2_final.pdf)

8DOH-HEMS Health Situation Update No. 7 as of December 6, 2013.

9Minutes of the Region 8 Nutrition Cluster Meeting, January 24, 2014.

10Source: Nutrition Survey Using the SMART Method in Typhoon Haiyan-affected Areas of Region VI, VII and VIII. The Philippines: 03 February – 14 March 2014.(http://www.humanitarianresponse.info/operations/philippines/document/nutrition-survey-using-smart-method-final-report)

11https://www.facebook.com/UnangYakap; http://www.wpro.who.int/topics/reproductive_health/maternal_child_health_brochure.pdf?ua=1