Timely expansion of nutrition development activities in repose to an acute flooding emergency in Malawi

By Natasha Lelijveld, Elizabeth Molloy, Jennifer Weiss, Gwyneth Hogley Cotes

By Natasha Lelijveld, Elizabeth Molloy, Jennifer Weiss, Gwyneth Hogley Cotes

Natasha Lelijveld has recently completed a nutrition research project in Blantyre, Malawi and is undertaking a PhD at UCL. She volunteered to assist Concern Worldwide during their nutrition response to the flooding in Nsanje District.

Natasha Lelijveld has recently completed a nutrition research project in Blantyre, Malawi and is undertaking a PhD at UCL. She volunteered to assist Concern Worldwide during their nutrition response to the flooding in Nsanje District.

Elizabeth Molloy is an education and gender specialist with experience in The Gambia, Nepal and Ethiopia. She was Concern Worldwide’s Education Programme Coordinator, based in Nsanje district (2013-2015), and managed Concern’s emergency nutrition and protection responses post Jan 2015 floods.

Elizabeth Molloy is an education and gender specialist with experience in The Gambia, Nepal and Ethiopia. She was Concern Worldwide’s Education Programme Coordinator, based in Nsanje district (2013-2015), and managed Concern’s emergency nutrition and protection responses post Jan 2015 floods.

Jennifer Weiss, MPH is the Health and Nutrition Coordinator at Concern Worldwide in Malawi. Jenn has over ten years of experience in the design, implementation, and evaluation of community-based maternal and child health, nutrition, and HIV/AIDS programmes.

Jennifer Weiss, MPH is the Health and Nutrition Coordinator at Concern Worldwide in Malawi. Jenn has over ten years of experience in the design, implementation, and evaluation of community-based maternal and child health, nutrition, and HIV/AIDS programmes.

Gwyneth Hogley Cotes, MPH is Programmes Director for Concern Worldwide, leading Concern’s programming, development, and advocacy work in Malawi. She has spent the past 12 years working as a manager and technical advisor in a range of nutrition and health issues.

Gwyneth Hogley Cotes, MPH is Programmes Director for Concern Worldwide, leading Concern’s programming, development, and advocacy work in Malawi. She has spent the past 12 years working as a manager and technical advisor in a range of nutrition and health issues.

Location: Malawi

What we know: Scale up of CMAM services at country level relies heavily on health system capacity that may be already overburdened. Surge response in emergencies and to seasonal peaks in malnutrition is necessary in many contexts but an added challenge.

What this article adds: Malawi was affected by severe flooding in early 2015 prompting cluster activation, including nutrition. Concern and UNICEF quickly responded in Nsjane district to support existing CMAM services to meet increased need but exposing weaknesses in doing so. Despite longstanding investment, services were not up to standard, not truly integrated and unable to surge to respond; volunteers were successfully used in the short-term to help compensate for already overburdened staff. Integration was also lacking in INGO led activities. Better preparedness, support for ‘true’ integration and stronger inter-sectoral (including cluster) coordination and communication would have strengthened the response.

In early January 2015 heavy rains, four times the monthly average, caused the most severe flooding seen in Malawi for over two decades. The floods affected 15 districts and an estimated 638,000 people countrywide. At least 174,000 people were displaced in the three most affected districts: Nsanje, Chikwawa, and Phalombe. Nsanje District, already amongst the poorest districts in the country, was the worst affected, with an estimated 170 deaths as of January 17th 2015, and a joint district assessment identified 15,274 households (approximately 84,000 individuals) who had been displaced or suffered severe damage.

In the days and weeks following the flooding, internally displaced persons (IDPs) gathered in makeshift camps, looking for shelter and support. Floods had washed away houses, crops and livestock, leaving families with limited access to food or income.

By February 2015, 19 camps had formed in Nsanje district, housing around 400-500 households each. Management of the camps was complicated with no one organisation taking full management responsibility. Additionally Malawi does not have a standing cluster system, and instead activated clusters (including shelter, logistics, food security, WASH, protection, education, and nutrition) soon after the emergency under the coordination of the Malawi Government and Humanitarian Country Team with support from UNDAC (UN Disaster Assessment and Coordination). The donor response was rapid and adequate; in this instance, funds tended to be channelled through NGOs and UN agencies rather than the Malawi government.

The destruction of bridges and roads by floodwaters meant that much of Nsanje district was cut off and difficult to access. IDPs whose homelands were located on seasonal floodplains were prevented from returning home and the process of their relocation to less risky land remains uncertain due to tensions with host communities and confusion over land ownership.

After the initial response, which focused on shelter, food and clean water, Concern Worldwide, with financial and technical support from UNICEF and in collaboration with the Nsanje District Health Office, provided emergency technical support, training, logistical support and supervision for nutrition services aimed at preventing and treating acute malnutrition among children under five years and pregnant and lactating women. These activities began in Nsanje district on 26 January 2015, 12 days after the worst of the flooding occurred.

Prior to the flooding, Concern Worldwide already had existing livelihoods and education programmes within Nsanje, with staff based in the district full-time, including education, food security, finance, administration and transport personnel. From 2005 to 2010, Concern Worldwide supported the scale up of CMAM services in the district, after which support for nutrition activities was handed over to the District Health Office. Due to their existing presence in the community, Concern Worldwide were closely involved in coordination efforts both in Nsanje District and at the national cluster level, and were in a strong position to lead on a timely nutrition intervention.

Activities

Supporting government health facilities

There are 14 health centres in Nsanje district and one district hospital. Community based Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM) is provided within all health facilities through the primary health care system in Malawi. Management of CMAM activities is delivered through the government health system, with financial, technical and logistical support from UNICEF. Concern Worldwide assessed all health facilities using the Nutrition Cluster data collection tool. Assessments found that there was a lack of IEC (information, education and communication) materials and job aids in most centres and inadequate documentation on screening by Health Surveillance Assistants (HSAs). At the time the flooding hit, CMAM activities were focused primarily on provision of outpatient and inpatient therapeutic care at health facilities. Community or facility-based screening did not happen regularly and supplementary feeding services were sporadic or inactive due to lack of food supplies. The assessment found that facilities had a reliable Ready to Use Therapeutic Food (RUTF) supply chain in place and staff had received appropriate training. Concern Worldwide’s initial response to this was to distribute job aids, such as RUTF ration charts, to health facilities and to begin supportive supervision of Outpatient Therapeutic Programmes (OTP) and Supplementary Feeding Programmes (SFP) across the health facilities in cooperation with the District Health Office.

Extending nutrition services to IDP camps

At their peak, the IDP camps varied in population size from over 9,000 people in the largest, to 600 people in the smallest. Through assessment of the 19 camps, Concern Worldwide found that they all reported availability of cooking and eating utensils and water was supplied either through a borehole or by water bowser visits. WFP was responsible for monthly deliveries of food rations, consisting of maize flour, beans and oil, to all camps. Despite these rations, the diets of most camp residents were poor, consisting of one meal per day of maize flour and legumes. Cooking was taking place in family groups using open fires and firewood collected locally.

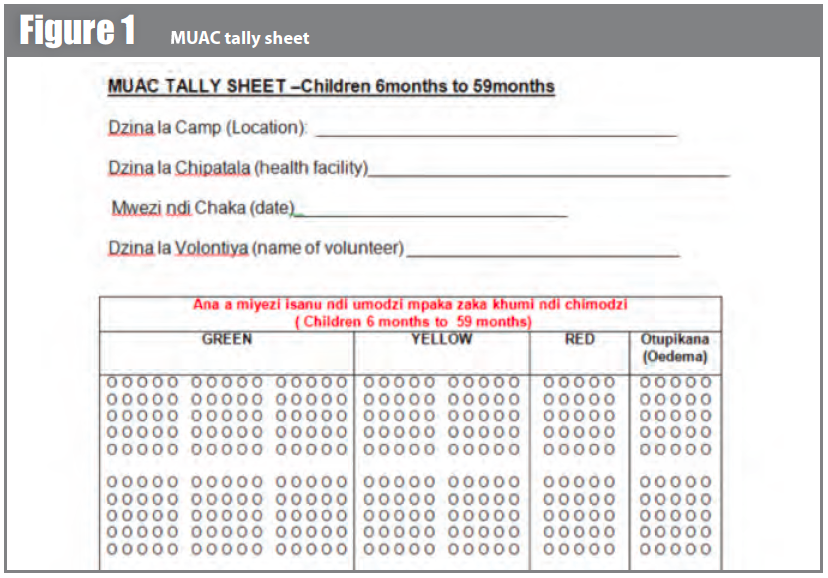

In order to extend CMAM services to the IDP camps, Concern Worldwide recruited and trained 10 Nutrition Volunteers from each camp. These volunteers were identified by the camp management committee and were required to be literate, willing to help and reside full-time in the camp. At each camp, Concern Worldwide provided a half-day orientation to the volunteers on how to screen for acute malnutrition using MUAC and assess for nutritional oedema. Each volunteer was equipped with one MUAC tape and a screening tally sheet (see Figure 1). Some HSAs working in the camps also participated in the training. Volunteers were instructed that camp-wide screening would take place each week, for at least three months. Each child under 5 years and pregnant and lactating women were screened; any cases of moderate or severe malnutrition were referred to the HSA or health facility for further assessment and appropriate management. Most camps were within the catchment area of their allotted health centre. However, due to flooding and inaccessibility, some health centres had to support camps several kms away, increasing their catchment population considerably and stretching resources, particularly staff, supplies and fuel.

The use of tally sheets allowed the screening exercise to also function as a monitoring system, with numbers of children screened and referred collected weekly and then analysed through a national nutrition information dashboard service managed by the Clinton Health Access Initiative. Initial screening reported a slightly elevated prevalence of global acute malnutrition (GAM) in the camps (9%), but a low prevalence of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) (1%). GAM rates in Malawi are usually between 4-6% (Malawi DHS, 2010). Both SAM and MAM cases identified by volunteers were referred to the nearest health centre for treatment. It is hoped that continuation of this intervention will result in prevention of further SAM cases though active case-finding and therefore early intervention.

Support to Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF)

In addition to MUAC screening, Nutrition Volunteers also conducted outreach education on IYCF messages following a 2-day training course, using simplified versions of government nutrition education booklets, translated into the local language. Thirty HSAs also joined this training. The integration of hygiene messages proved particularly important as the risk of cholera was high in the area, following an outbreak originating in the neighbouring Jamila province in Mozambique. However, mothers found it challenging to implement the IYCF guidance they were given due to the lack of diverse sources of food available to them. There was some anecdotal evidence that households were supplementing their diets with purchased foods from the surrounding community but camp diet assessments did not find that to be adequate. Given the acute nature of the emergency, and the fact that most households were expected to remain in camps for only a short time before returning to their homes, Concern Worldwide focused on advocating through the food security and agriculture clusters for appropriate and diverse materials for the winter planting season. A number of donors responded to this need, providing seeds and cuttings for maize, beans and orange-fleshed sweet potato.

Key challenges and learning points

Accessibility proved to be a great challenge for all nutrition activities, especially orienting and supporting the camp-based volunteers. With flood water levels fluctuating greatly day by day following rain or periods of sunshine, it proved difficult to access the six camps in the eastern part of the district, which had been cut off by flood waters and hosted the greatest population of IDPs. WFP operated a passenger helicopter from mid-January until March 23rd. Following the end of helicopter operations, the WFP-led logistics cluster developed innovative ways to access Nsanje’s eastern bank camps, such as the use of an airboat to navigate the fluctuating water levels of the River Shire. Malawi, being a land-locked and resource-limited country, does not have necessary transportation equipment, such as boats and helicopters, needed to respond to major flooding. This limitation needs to be considered and better planned for in similar situations in the future.

Secondly, the existing health infrastructure in Nsanje district, which this nutrition programme supported, suffered from a number of challenges. Malawi was one of the first countries to embrace and roll out CMAM programmes nationally and provides CMAM services in more than 80% of facilities. However, as the CMAM activities are delivered as a separate clinic one day per week, it appeared to be seen as an ‘add-on’ to routine health services rather than an integral component of routine child health services and was often deprioritised by health staff. Routine screening and community outreach, which is intended to be done by HSAs, was rarely done. This made the nutrition response to the flood more difficult, with the need to recruit and train additional volunteers to handle community screening. From the period 2010 to 2013, several specific initiatives that aimed to support the scale-up of CMAM came to an end, such as NGO-supported nutrition programmes and the CMAM Advisory Service. There seems to have been a general erosion of the programme affecting training, supervision and resources following the reduction of these support services. For example, replacing broken weighing scales with functioning ones in health centres was slow to happen and there were reports that fuel for supervisors to make visits to rural health centres was lacking.

Secondly, the existing health infrastructure in Nsanje district, which this nutrition programme supported, suffered from a number of challenges. Malawi was one of the first countries to embrace and roll out CMAM programmes nationally and provides CMAM services in more than 80% of facilities. However, as the CMAM activities are delivered as a separate clinic one day per week, it appeared to be seen as an ‘add-on’ to routine health services rather than an integral component of routine child health services and was often deprioritised by health staff. Routine screening and community outreach, which is intended to be done by HSAs, was rarely done. This made the nutrition response to the flood more difficult, with the need to recruit and train additional volunteers to handle community screening. From the period 2010 to 2013, several specific initiatives that aimed to support the scale-up of CMAM came to an end, such as NGO-supported nutrition programmes and the CMAM Advisory Service. There seems to have been a general erosion of the programme affecting training, supervision and resources following the reduction of these support services. For example, replacing broken weighing scales with functioning ones in health centres was slow to happen and there were reports that fuel for supervisors to make visits to rural health centres was lacking.

The HSAs, a fundamental part of the CMAM programme and overall health system, were actively involved in responding to needs of the flood-affected population, but lacked skills and knowledge in delivering emergency health and nutrition activities. This emergency response highlighted the many responsibilities delegated to HSAs and their large workload meant that some tasks were not prioritised, as was the case with CMAM surveillance. It quickly became clear as nutrition activities began to be implemented that the HSAs would not be able to play as large a role as imagined due to their already high workload and volunteers were recruited to support with screening and referral.There are many opportunities for better integrating nutrition activities into routine health services in Malawi, such as twice-yearly Child Health Days, outpatient clinic visits and iCCM (Integrated Community Case Management. A Health Facility Assessment conducted by Concern in 2014 found that nutrition actions such as screening and counselling are rarely carried out as a part of sick child visits or other routine maternal and child health contact points. If CMAM services and nutrition actions were better integrated into routine child health services, this could ease the burden on health personnel, particularly HSAs.

There is a need to work with the health system to better plan for increased resource requirements during both emergencies and also during routine spikes in malnutrition during the lean season. The CMAM Surge model, piloted by Concern Worldwide in Kenya, is an approach to strengthening the capacity of health service providers to identify and respond to surges in caseloads; it could be applied in other settings to improve routine CMAM activities and better prepare the health service for emergency response. The CMAM surge model employs capacity-based response thresholds that trigger support based on existing health system capacity. The model aims over time to improve health system capacity to manage spikes in cases of acute malnutrition. The support components align with the WHO’s health system building blocks, including elements for health workers, information and leadership.1

As a result of the heavy workload of HSAs, the camp-based nutrition volunteers took on a more prominent role in this intervention. The motivation of the volunteers was higher than expected and the nutrition programme not only aimed to prevent and treat malnutrition, but gave other members of the camp a meaningful role in their new camp society. IDP camps can be boring and demoralising places and these volunteers were grateful for the activity and status that came with MUAC screening and IYCF messaging. Although this method was successful, it could have been improved had the volunteers been integrated with other services. There were missed opportunities to combine MUAC screening and IYCF messaging with either the vitamin A campaign or the camp health clinics run by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). Despite the merging of the health and nutrition clusters, due to low numbers of agencies participating in the nutrition cluster, opportunities for coordination were unexploited, with health clinics seeing many women and children without screening for malnutrition.

Coordination and communication could have been improved throughout the emergency. Coordination with both government officials and other organisations was initially strong immediately following the flooding however it quickly tapered off as the weeks passed, with information being shared in an ad-hoc manner rather than through formal structures. Although the joint health-nutrition cluster continued to be active, meetings became less frequent and more poorly attended. Additionally, communication to and from the national level clusters was inconsistent. Access to accurate and relevant data was also an issue both before and during the nutrition response; however the simple tally sheet used by nutritional volunteers proved an invaluable source of data and was an adequate stand-in for a costly nutrition survey.

Conclusion

Many children in Nsanje District in Malawi are experiencing their first 1000 days during an emergency flood crisis. The risk of malnutrition due to loss of resources and threat of infections is high; therefore the importance of preventing heightened levels of malnutrition throughout the 1st 1000 days is urgent. Concern Worldwide, with support from UNICEF, responded to this need by setting up support for health centres, CMAM screening and referral and IYCF outreach messages within 12 days of the emergency. Better integration of nutrition services into routine services could result in a more sustainable CMAM programme. In addition, better inter-sectoral coordination and communication would have strengthened the response and improved efficiency of activities, with opportunities for ‘piggy-backing’ interventions maximised. Exploring a model for strengthening surge capacity in health facilities, as used by Concern Worldwide in Kenya, could strengthen both data management and the health facilities in their capacity to respond to sudden increases in caseloads, such as this flood emergency.

For more information, contact: Jennifer Weiss, email: Jennifer.Weiss@concern.net

1For more detail on the CMAM Surge model, see Field Exchange issue 47: Regine Kopplow, Yacob Yishak, Gabrielle Appleford and Wendy Erasmus (2014). Meeting demand peaks for CMAM in government health services in Kenya.).