Practical pointers for prevention of konzo in tropical Africa

By J.H Bradbury, J.P.Banea, C. Mandombi, D, Nahimana, I.C. Denton and N. Kuwa

Dr J Howard Bradbury, Emeritus Fellow, Australian National University, developed the cassava cyanide and urinary thiocyanate kits and the wetting method that removes cyanogens from cassava flour,

Professor Jean Pierre Banea is Director of the National Institute for Nutrition (PRONANUT) in Kinshasa, DRC and directed all the field work.

Sister (Dr) Chretienne Mandombi of Caritas examined patients for konzo and lead the small team that visited the villages monthly.

Mr Damien Nahimana directs the full team and oversees training in the wetting method and collectiona and analysis of samples of flour and urine.

Mr Ian C Denton assists in preparation and despatch of cyanide and urinary thiocyanate kits at ANU.

Mrs N'landa Kuwa is involved with food surveys to check on malnutrition and training of women in use of wetting method.

Konzo is an upper motor neuron disease of sudden onset that causes irreversible paralysis of the legs mainly in children and young women, due to high cyanide intake and malnutrition from consumption of a monotonous diet of bitter cassava.1 Konzo occurs in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Mozambique, Tanzania, Cameroon, Central African Republic and Angola and is spreading into new areas with increasing cassava production needed to feed rapidly increasing populations. In the DRC, konzo occurs in at least four provinces and in 2002, there were an estimated 100,000 cases. The disease was first reported in Bandundu Province, DRC in 1938 and it was first prevented there in 2011, by the daily use by village women of a new simple wetting method, that removes nearly all residual cyanogens present in cassava flour produced by traditional methods. We wish to share our experiences of the practical aspects of the prevention of konzo using the wetting method in similar contexts.

1. Choice of villages for intervention. The regional and local health authorities are consulted and they usually know the extent of konzo in their area; if this is not known, a survey for konzo cases may be needed.2 The choice of villages in which interventions are to be made depends on the konzo prevalence in the village, the presence of capable village leaders, their willingness to be involved in the project and the accessibility of the village to a 4 wheel drive vehicle. A first visit is necessary to choose suitable villages for an intervention.

2. Intervention team. The team must include (a) a medical doctor familiar with the diagnosis of konzo3 and rehabilitation of those with konzo, (b) a teacher to explain in the local language the cause of konzo and to teach the women how to use the wetting method, (c) a person trained to make a census of the village and conduct a food consumption survey used to assess the extent of malnutrition and (d) a technician trained to collect and analyse urine samples from school children for thiocyanate and cassava flour samples for cyanide.4

3. Second visit to konzo villages. About one month later, baseline data are obtained on population, numbers of konzo cases, urinary thiocyanate analyses made on site from 50 school children. Approximately 30 cassava flour samples analysed for cyanide and food consumption data are then obtained from konzo and non-konzo households. The senior women are subsequently taught about the poisonous cyanide present in cassava flour and the means to remove it using the wetting method. This is shown to them by the teacher as follows:

“Cassava flour is placed in a bowl and the level is marked on the inside of the bowl. Water is mixed in and the level of the flour at first decreases and then increases up to the mark. The flour is spread in a thin layer about 1 cm deep on a mat in the sun for two hours or the shade for five hours to allow hydrogen cyanide gas to escape. The treated flour is mixed with boiling water to make the traditional thick porridge called fufu.”

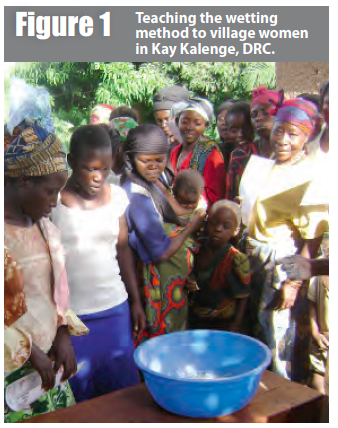

Each senior woman then trains 15-20 village women to use the wetting method until all the women in the village are trained (see Figure 1). A committee of the leading women is formed to ensure that all the women are trained in the wetting method and that it is used on a regular daily basis to remove cyanogens. Each household is given a plastic bowl, knife, mat and an illustrated poster which explains the wetting method in their own local language.

4. Subsequent visits to konzo villages. After the second visit, a small team visits each month to check on konzo cases and that the wetting method is still being used daily. Four months after the second visit, there is another visit of the full team to check urinary thiocyanate and flour cyanide levels. This is followed by three monthly visits of the small team and a final visit by the full team to conclude the nine month intervention.

5. Targets: Village women are very satisfied with the wetting method and at least 60-70% need to use it daily for it to be effective.5 Recently in Mozambique, only about 40% used the method, because there were very few new konzo cases in the villages and hence there is less incentive for the women to use the wetting method than where there are recent konzo cases as in DRC. However, it is expected that this attitude would change under drought conditions when the cyanide content of flour increases very greatly6 and konzo outbreaks occur.

During the intervention there are no new konzo cases. At the end of the intervention, mean cassava flour cyanide levels are less than 10 ppm and no children have high urinary thiocyanate levels of >350µmole/L.

Years after completion of the intervention, there are no new konzo cases in the villages, the wetting method is still being used and it’s use has spread by word of mouth to nearby villages.7

6. Cost of intervention. Our first intervention took 18 months8 but now takes 9 months.9 We have undertaken interventions in 13 villages reaching nearly 10,000 people. The cost per person has been reduced to $16,10 but could be reduced further by scaling up the operation.

7. Comparison of preventing konzo by reducing malnutrition or reducing cyanide intake. A cross-sectoral approach has been used to reduce malnutrition and prevent konzo in Kwango District11 but this approach is less direct and much more expensive than our methodology, which greatly reduces uptake of poisonous cyanide from cassava.

Funding is needed to continue work to prevent konzo amongst poor village children and young women.

For more information, contact: Dr J Howard Bradbury, email: Howard.Bradbury@anu.edu.au or Professor Jean Pierre Banea, Director PRONANUT, email: jpbanea@yahoo.fr

1Banea JP, Bradbury JH, Mandombi C, Nahimana D, Denton IC, Foster MP, Kuwa N and Tshala Katumbay D, Konzo prevention in six villages in the DRC and the dependence of konzo prevalence on cyanide intake and malnutrition. Toxicology Reports, 2, 609-615 (2015).

2Banea JP, Bradbury JH, Nahimana D, Denton IC, Mashukano N and Kuwa N, Survey of the konzo prevalence of village people and their nutrition in Kwilu District, Bandundu Province, DRC. African J. Food Sci., 9: 45-50, (2015).

3World Health Organisation, Konzo: a distinct type of upper motor neuron disease. Weekly Epidemiol. Rec. 71: 225-232 (1996).

4See http://biology.anu.edu.au/hosted_sites/CCDN

5See footnote 1.

6Cardoso AP, Mirione E, Ernesto M, Massaza F, Cliff J, Haque MR and Bradbury JH, Processing of cassava roots to remove cyanogens. J. Food Comp. Anal. 18: 451-460 (2005).

7Banea JP, Bradbury JH, Mandombi C, Nahimana D, Denton IC, Kuwa N and Tshala Katumbay D, Effectiveness of wetting method for control of konzo and reduction of cyanide poisoning by removal of cyanogens from cassava flour. Food Nutr. Bull. 35: 28-32 (2014).

8Banea JP, Nahimana D, Mandombi C, Bradbury JH, Denton IC and Kuwa N, Control of konzo in DRC using the wetting method on cassava flour. Food Chem. Toxicol. 50: 1517-23 (2012).

9See footnote 1.

10See footnote 1.

11Delhourne M, Mayans J, Calo M, Guyot-Bender C. Impact of cross-sectoral approach to addressing konzo in DRC. Field Exchange, No. 44, 50-54 (2012).

English

English Français

Français Deutsch

Deutsch Italiano

Italiano Español

Español