Challenges in addressing undernutrition in India

By Ajay Kumar Sinha, Dolon Bhattacharyya and Raj Bhandari

Ajay Kumar Sinha (left) is the Founder Secretary and Executive Director of FLAIR. He is an expert on public policy and public finance. Dolon Bhattacharyya (middle) is an expert on budget analysis and is the Director of Policy, Research and Documentation at FLAIR. Dr Raj Bhandari (right) is a senior paediatrician and technical advisor to various committees on health and nutrition. He has actively collaborated with UNICEF and Government for more than a decade to scale up nutrition programmes in various States of India. He is the chief mentor of FLAIR.

Ajay Kumar Sinha (left) is the Founder Secretary and Executive Director of FLAIR. He is an expert on public policy and public finance. Dolon Bhattacharyya (middle) is an expert on budget analysis and is the Director of Policy, Research and Documentation at FLAIR. Dr Raj Bhandari (right) is a senior paediatrician and technical advisor to various committees on health and nutrition. He has actively collaborated with UNICEF and Government for more than a decade to scale up nutrition programmes in various States of India. He is the chief mentor of FLAIR.

FLAIR (Forum for Learning and Action with Innovation and Rigour) is a forum of expert individual researchers and practitioners, as well as organisations, which was formally registered as a Society in June 2013. It draws from the experience and expertise of the founding individuals and organisations. FLAIR creates, nurtures and operates the spaces for learning by organising and/or facilitating consultative processes, seminars, lectures, etc. It works through (a) participation in the processes of policy and programme formulation via research and development of protocols and standardised operating procedures (SOPs) based on a combination of learning from grassroots and inputs from sector and subject experts, (b) programmes in the social development sector that interface with Information and Communications Technology (ICT).

The context

The context

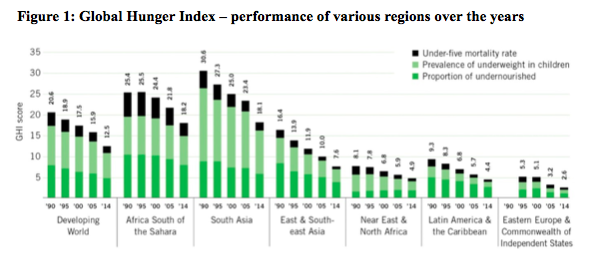

The Global Hunger Index1 (a composite of under-five mortality rate, prevalence of underweight in children and proportion of undernourished) for South Asia, East and Southeast Asia remains “serious” and warrants continued concern (see Figure 1). Although India’s 2014 GHI score fell to 17.8, it remains in the ‘serious’ category. The progress in reducing child malnutrition (underweight2) in India has been commendable, decreasing from 43.5% in 2005-6 to 30.7% in 2013-14. However, India is still ranked 120th among 128 countries with data on child undernutrition from 2009 to 2013; much work is needed at national and state levels so that a greater share of the population can enjoy nutrition security. India ranks highest out of all countries with respect to annual incidence of deaths of children below 5 years; in 2012, there were 1.4 million deaths amongst children under the age of five years3.

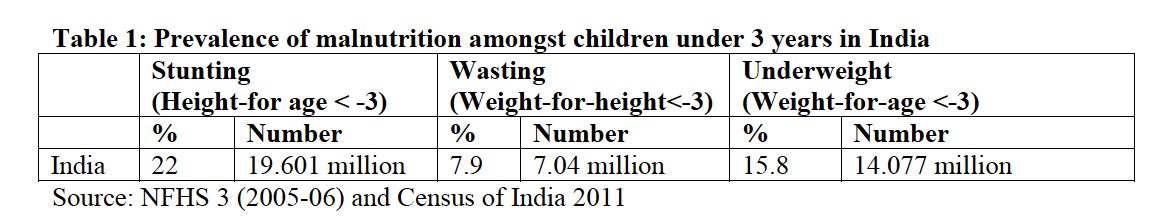

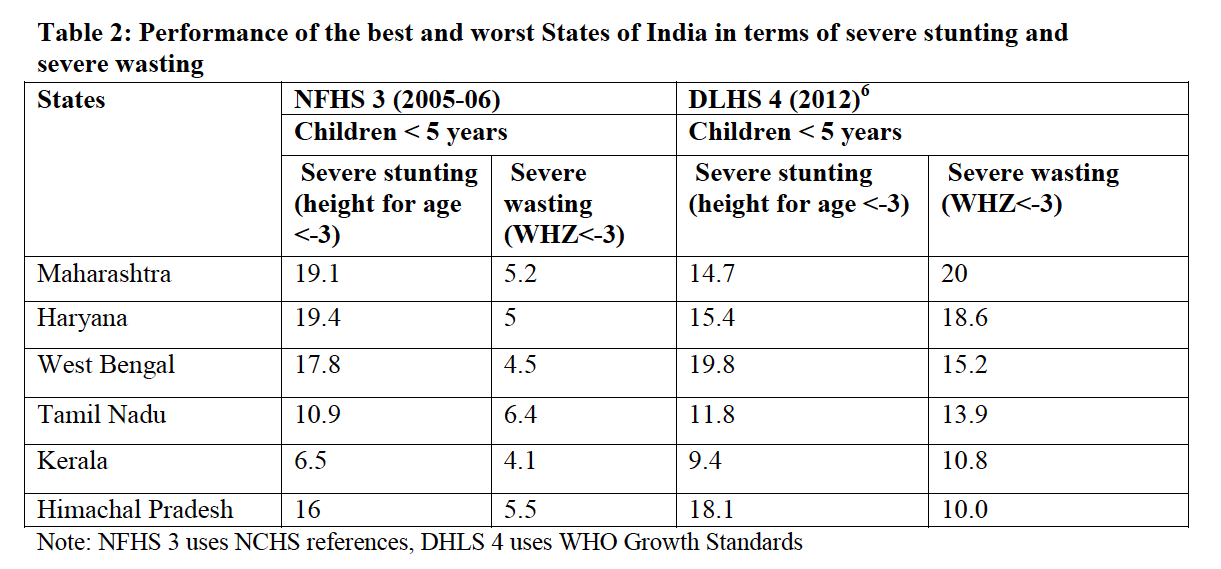

The prevalence of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) (weight for height <-3 z-scores) is estimated to be 7.9% in India (as per the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) 3, 2005-06) , translating to approximately seven million children under 3 years of age with SAM (see Table 1). At the present rate of progress, the country is unlikely to meet the Millennium Development Goals related to eradicating hunger and malnutrition and improving maternal and child health4. Whilst more recent data on malnutrition prevalence is available, these data are challenging to interpret. Variations in target age-group and survey timing, different references/standards5, lack of qualitative information to aid interpretation of prevalence figures and lack of serially consistent data to track change all hamper analysis and conclusions. With these limitations in mind, the latest malnutrition prevalence data comes from the District Level Household Survey – 4 (DLHS 4), conducted in 2012-13. However, as not all the data have been analysed, in this article we only compare SAM prevalence (WHZ < -3) between DLHS 4 and NFHS 3 in the three best performing and three worst performing Indian States (see Table 2). It is important to note that while NFHS -1 and NFHS -2 assessed children under 3 years, both NFHS 3 and DLHS 4 assessed children under 5 years.

Severe wasting is considerably higher in DLHS 4 and indicates prevalence at a phenomenal ‘emergency’ level of 20% (34% global acute malnutrition) in the state of Maharashtra, for example. There is a lack of contextual data to help explain this extreme prevalence; in fact, a number of smaller surveys have not indicated any increase in prevalence of SAM for children less than 3 or 2 years of age and in some cases have shown a decline, such as the Comprehensive Nutrition Survey in Maharashtra (CNSM) in 20117. Our field experience is that wherever Governments have worked with an integrated and comprehensive approach that combines addressing care and feeding practices with food based initiatives, there have been positive results for nutrition. But, without an intensive Government programme, nutrition insecurity takes its toll, especially on poor and marginalised families. Positive results seen in the CNSM could be attributed to good programming practices for pregnant women and lactating mothers and good infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices. Although the CNSM does not show nutrition improvement compared with NFHS 3, this may be related partly to differences in the target age group surveyed.

During our field experience of working in Maharashtra and other States of India, we have observed that Governments of late have been working on multiple fronts to address undernutrition. The Government of Maharashtra has taken a number of steps to reduce malnutrition with interventions focusing on pregnant mothers and the -9 to 24 months age group. Examples of state initiatives are included in Box 1. The results of this can be seen in a substantial reduction in measures of malnutrition including stunting and wasting prevalence between 2006 and 2012, as per the 2012 CNSM. Overall, it appears that there has been progress in programming for improvement of nutritional status of young children under 2 years of age. Less may have been achieved for the 2-5 years age group; however, strong conclusions cannot be drawn due to lack of data – in particular, a data subset for children below 2 years or 3 years from DLHS 4.

Box 1: State initiatives to address malnutrition in Maharashtra

- Addressing malnutrition issues in Mission Mode though Rajmata Jijau Health and Nutrition Mission (The Mission).

- IYCF and infant and young child nutrition (IYCN) as an integrated package through the Breastfeeding Promotion Network of India (BPNI), addressing anaemia among adolescents and linking with the Health and Education Department.

- Micronutrient drives through National Rural Health Mission (NRHM), such as biannual de-worming (12- 59 months) and vitamin A supplementation (9-59 months) rounds which have ensured a coverage of >75% among children under 5 since 2007.

- Take Home Rations introduced which makes it convenient for working mothers and adolescent girls.

- Janani & Shishu Suraksha Karyakram, free delivery services, free transport and food, free antenatal care (ANC) check- ups during pregnancy, weekly visits of gynaecologists to primary health centres (PHCs) for check-up of pregnant women, free iron and folic acid (IFA) tablets for pregnant women – all geared towards improvement in maternal health.

- The Supplementary Nutrition Programme (SNP) guidelines have been revised so that expenditure per child and the calories allocated have increased. Severely underweight children between 6 months to 3 years old are provided with 950 kcals and 23-28g of protein. The revised cost is Rs 9.00 per day per beneficiaries8.

- Models of Village Child Development Centres (VCDCs) have been developed with funding support from the NRHM to allow identification of SAM and moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) by measuring weight-for-height in addition to weight-for-age.

- Home based VCDC for home based management of SAM and MAM children, the ‘anganwadi' model and the 'muthhi bhar dhanya' model; the latter invokes donation of food grains by the village community to the households that have malnourished children.

- Regular training programmes on child care, nutrition, care during illness etc. involving Integrated Management of Neonatal and Childhood Illnesses (IMNCI), IYCN, Home Based Newborn Care (HBNC), breastfeeding etc. funded by the NRHM.

- Raising awareness about the importance of 10 essential interventions, e.g. breastfeeding, complementary feeding, etc and about ICDS services including the television series ‘Deshache Dhan’ on the ICDC services and the monthly newsletter ‘Aamchi Aanganwadi’ on the latest schemes, anecdotes and stories from the field.

- Other innovations, such as the malnutrition free village campaign implemented by The Mission, the crèche scheme operational in six tribal districts through Gram Panchayat and the mobile Anganwadi project for migrated population.

Source: Annual Project Implementation Plan, 2012-2013, ICDS, Dept of Women and Child Development, Government of Maharashtra

Factors to improve nutritional status of children in India

It is commonly accepted that the factors to address which will lead to improvements in nutritional status of children in India are a) nutritional status of women preconception and during pregnancy; b) infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices; c) dietary intake of children and lactating mothers; and d) availability of safe, clean drinking water, sanitation and hygiene facilities. All these factors are associated with social grouping and the income categories of the households to which the children belong.

a) Nutritional status of women

a) Nutritional status of women

Children born to short, thin women are more likely themselves to be stunted and underweight (low weight for age). Data shows 21.5% of children in India are born with low birth weight (LBW), i.e. below 2.5 kg. Anaemia remains a critical public health problem affecting 51.2% of women9 and 49.4% of children aged 6-35 months10 in India. Anaemia begins in childhood, worsens during adolescence in girls and is aggravated during pregnancy., The prevalence of anaemia is high because of low dietary intake of iron (<20 mg/day) and folic acid; poor bio-availability of iron (3-4% only) in the phytate and fibre-rich Indian diet; and chronic blood loss due to infectious diseases (faecal iron loss in the context of parasitic infections)11 or consecutive child births12. Data shows that only 46.6% of mothers in India have consumed 100 IFA tablets as prescribed during pregnancy13.

b) IYCF practices

The risk of increased morbidity and mortality due to pneumonia and diarrhoea is higher for infants who are not exclusively breastfed14. According to NFHS 3 (2005-06), while breastfeeding is nearly universal in India, very few children are put to the breast immediately after birth. Only one-quarter of last-born children who were ever breastfed started breastfeeding within the recommended half an hour of birth, and almost half (45%) did not start breastfeeding within one day of birth. Fifty-seven per cent of mothers gave their last-born child something to drink other than breastmilk in the three days after delivery. Only 69% children below two months of age are exclusively breastfed. Exclusive breastfeeding drops to 51% at 2-3 months of age and 28% at 4-5 months of age. Overall, slightly less than half of children under six months of age are exclusively breastfed15.

NFHS – 3 (2005-06) also shows shortcomings in complementary feeding practices amongst both breastfed and non-breastfed 6-23m children. Only 21% of breastfed and non-breastfed children are fed appropriately according to all three recommended IYCF practices16, which varies widely among the states. Appropriate feeding practices are followed most often in Kerala and Sikkim, but even in these two states a large percentage of children are not fed appropriately according to all three IYCF practices. Other states with much better than average feeding practices are Goa, Manipur, Himachal Pradesh, and Delhi. Compliance with all recommended feeding practices is lowest in Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra, where only 1 in 10 children are fed according to all three IYCF practices17.

c) Food intake

In spite of India's rapid economic growth, there has been a sustained decline in per capita calorie and protein consumption during the past 25 years18. Deficiencies in micronutrients such as vitamin A, beta-carotene, folic acid, vitamin B12, vitamin C, riboflavin, iron, zinc, and selenium influence the vulnerability of a host to infectious diseases and the course and outcome of such diseases.

d) Issues of safe drinking water, sanitation and hygiene

Research suggests that an unhygienic environment, combined with high population density, creates a perfect storm for diseases to thrive and malnutrition to flourish in India. Residents of nearly 59.4% of the country’s rural homes defecate in the open19, exposing children to infectious diseases such as typhoid and diarrhoea, which reduces nutrient absorbtion. Madhya Pradesh, Bihar and Jharkhand have both the highest percentage of homes having no toilet facilities20 and highest child malnutrition prevalence. Conversely, states like Kerala, Manipur, Mizoram and Sikkim, where 80% or more of the rural population have access to toilets, have the lowest levels of child malnutrition.

The effects of child undernutrition among the different social groups are reflected in higher neonatal mortality, child mortality, U5 morality rate (U5MR), LBW, etc. amongst the scheduled population (both Scheduled Caste (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST)21) compared to children of higher castes. The calorie intake of the poorest quartile continues to be 30 to 50% less than the calorie intake of the top quartile of the population in India22.

Existing nutrition interventions in India

The Indian government has rolled out and expanded several programmes that target a mix of direct and indirect causes of undernutrition amongst mothers and children. Direct nutrition-specific interventions include food supplementation programmes under the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS)23 and Mid-day Meals (MDM)24. The National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) aims to address micronutrient deficiencies through immunisation, IYCF, IFA distribution, communicable and non-communicable disease control programmes, etc. and pursues convergence between water, sanitation, education, nutrition and health programmes though implementing comprehensive programmes. Indirect causes of undernutrition are addressed through initiatives such as the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (a rural jobs programme) and reforms, in several states, to the Public Distribution System for improving household food security among the poor. Recent sanitation and hygiene initiatives by the Indian Government, such as the ‘Swachh Bharat Mission’ that involve construction of toilets in rural areas to eliminate open defecation are also important. However, current interventions do not address structural and systemic causes of India's malnutrition; they have poor coverage and miss important sections of the undernourished population. For example, ICDS does not recognise SAM and focuses supplementary feeding only on the 3-6 year old population.

Financing food and nutrition programmes

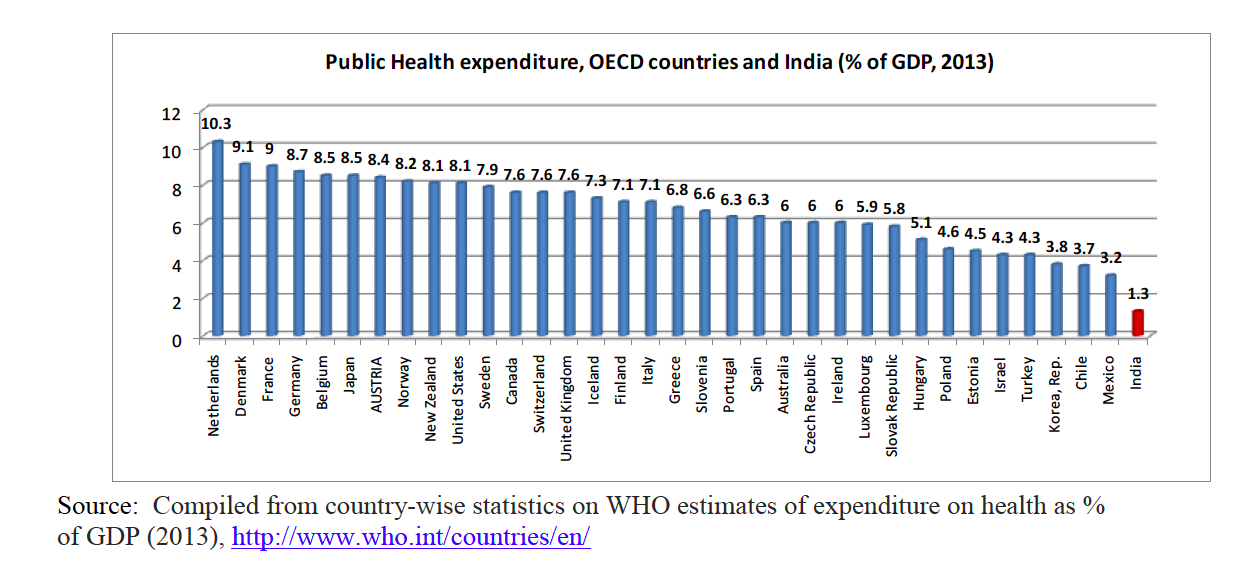

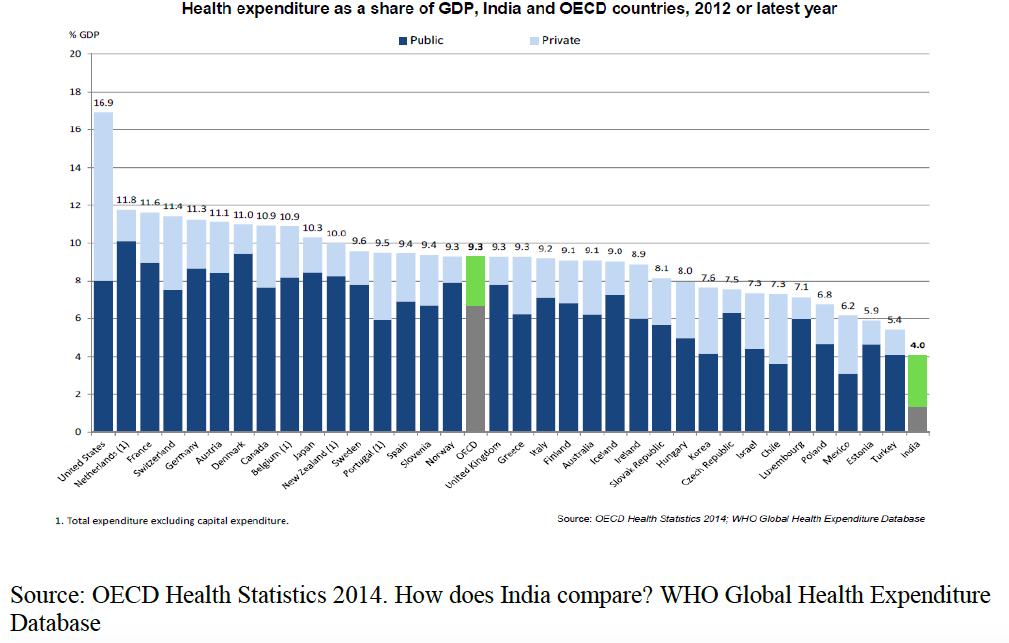

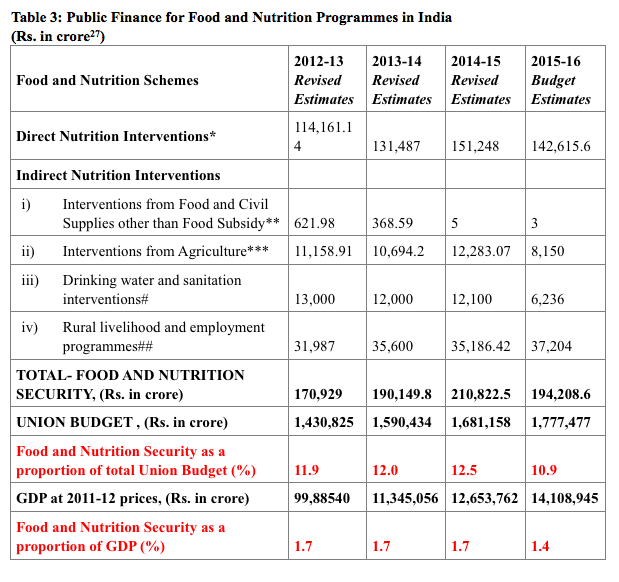

Malnourished children require more health services and more expensive care and treatment than well-nourished children. Yet, India has one of the lowest health spends as a proportion of gross domestic product (GDP). Public expenditure on health in India was 1.3% of GDP in 2013, ranking well below the OECD25 average of 6.7% (see Figure 2). The overall total expenditure on health in India stands at 4%, but it is mainly due to the contribution of the private sector (see Figure 3). As per a recent study on ‘Budget analysis of Food and Nutrition Programmes in India’ (forthcoming publication)26 by FLAIR, the share of expenditure on schemes27 in the Union Budget for achieving nutrition security averages 11.83% of the total country budget and only 1.63% of GDP % (between 2012-13 and 2015-16), which is inadequate given the extent of malnutrition in India (see Table 3).

Figure 2

Figure 3

Crucially, large amounts of public finance meant for preventing and treating undernutrition through interventions under the NRHM have also remained unspent in India. Interventions such as the National lodine Deficiency Disorders Control Programme and Reproductive and Child Health Project show under spend by 76% and 69% respectively for the financial year (FY) 2012-13. This is compounded by the overall inadequacy of funding for nutrition schemes. For example, in FY2015-16, only 57% of required funds were allocated for the MDM scheme for school children, while only 34% of necessary funding for the ICDS scheme was allocated by government in the same year29.

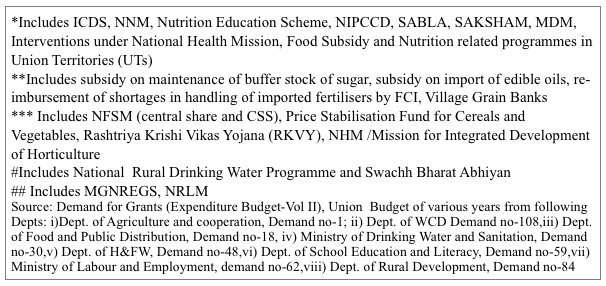

The burden of undernutrition is higher amongst children belonging to socially disadvantaged groups. There is a provision for earmarking allocations in the Government Budgets for these groups through the Special Component Plan (SCP) and Tribal Sub Plan (TSP). However, the Union Government has not been fulfilling SCP and TSP guidelines for earmarking Plan allocations for SCP and TSP in proportion to their representation in the population and allocations are still far below the required 17% and 9% respectively (based on 2011 Census)30. The share of allocation under SCP and TSP in total plan allocation in the Union Budget stands at 5.02% and 2.42 % respectively (as an average of FY 2012-13 to 2015-16)31 (see Figure 4).

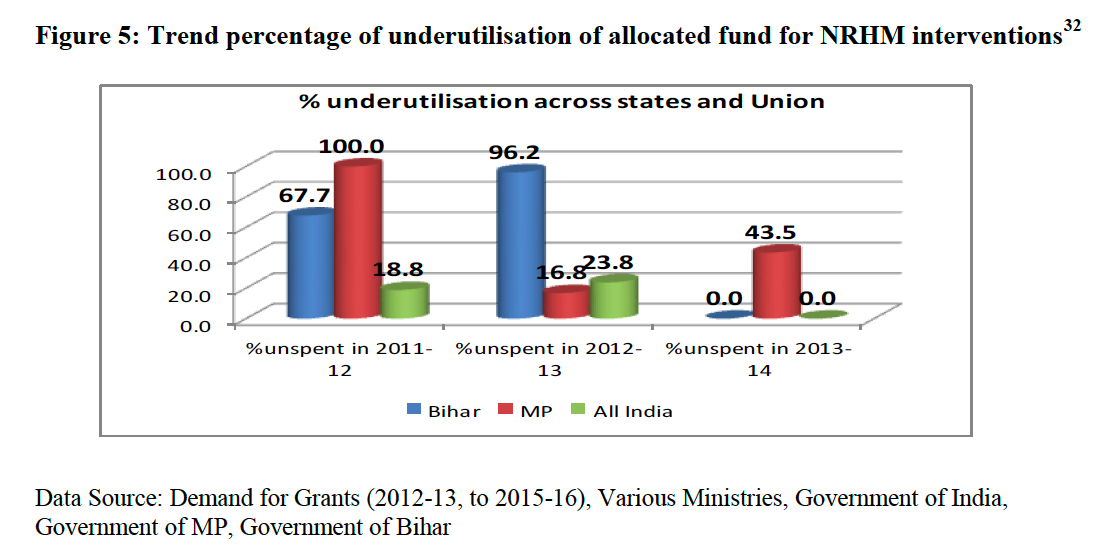

Micronutrient related schemes and schemes for disease control to combat malnutrition are budgeted under the NFHM in the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare in all the States. Here again, as reflected in Figure 5 and below, there has been massive under-expenditure in these programmes:

- India: National lodine Deficiency Disorders Control Programme and Reproductive and Child Health Project shows under spending by 76% and 69% respectively.

- Bihar: 78.1% and 49% of allocated funds for ‘Care of Sick Children and Severe Malnutrition’ and ‘Management of diarrhoea and acute respiratory infection (ARI) and Micronutrient Malnutrition’ were unspent in 2012-13.

- Madhya Pradesh: Programmes such as the National lodine Deficiency Disorders Control Programme, IYCF Programme, and the Micronutrient Supplementation Programme shows underspend by 33%, 27% and 73% respectively.

Thus we see that the crucial public finance meant for preventing and treating undernutrition as part of NFHM interventions are not only inadequately financed but that a substantial proportion of funds that are allocated remain unspent. The main reasons are inadequacy of infrastructure (so certain services cannot be delivered or scaled up), vacancy of staff and worker positions (thus activities are not implemented), delay in submission of utilisation certificates33 and delay in release of funds.

Priority areas

A major gap in India’s capacity to address undernutrition in India is the absence of programmes to both prevent and treat cases of childhood SAM. Energy dense food that is soft or crushable, palatable and easy for children to eat through community based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) need rapid scaling up in India. Operations research using energy dense food fortified with Type 2 micronutrients (magnesium, phosphorus, sulphur, lysine) is needed. Reductions in stunting are better achieved through interventions such as IYCF micronutrient supplementation for vulnerable children; access to high quality food; health care; safe water sources and basic sanitation. IYCF and CMAM should be conceptualised and planned as two integral parts of a single programme to prevent and treat undernutrition in its range of forms.

Quantifying need and determining impact of interventions is critical. However, in India, tracking programme performance over time is compromised by surveys that gather data on different child age groups. For example, CNSM (2012-13) collects data for children under 2 years of age, whilst NFHS 3 (2005-06) and DLHS 4 (2012-13) collected data for under-fives. DLHS 3 was conducted in almost the same reference period (2007-08) as that of NFHS 3 (2005-06), but DLHS-3 did not give information on any of the three indicators of malnutrition. DLHS 4 and CNSM are also of the same time reference period (2012-13), but the age group of children covered is different. As a result tracking change (improvement or decline) is hugely challenging.

Early identification and treatment of wasting may play a role in prevention of stunting in particular contexts. Programmes could be designed and directed to reduce wasting and stunting with preventive food based approaches. Policy, programme and finance should address the issue of wasting and stunting in an integrated way and attempt to bridge the divide between the two categories; it is unfortunate that neither the Ministry of Women and Child Development (WCD) nor the Health Department records length/height of children during growth monitoring promotion (GMP). The continuum of care has to be established and encompass preconception, during conception, natal and post-natal management of small for gestational age (SGA) babies, IYCF, complementary feeding, early detection of severe undernutrition by growth monitoring, disease prevention and treatment and care practices. Improvement in Maternal Health is also a priority action. Mid upper arm circumference (MUAC) standards appropriate for Indian children, should be used in community screening. Considering the high rate of small for gestational age (SGA) and preterm babies, there is an increased risk of children growing with Metabolic Syndrome, which is likely to triple the burden of malnutrition in future generations.

Finding solutions to malnutrition requires traversing many pathways and integrating interventions in multiple sectors including agriculture, food distributions, feeding and care practices, disease control, hygiene and sanitation and public health programmes for disease control. In India, these interventions and pathways fall under the portfolios of at least seven different ministries, e.g. Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Food and Public Distribution, Ministry of WCD, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Ministry of Water and Sanitation, Ministry of Rural Development, Ministry of Urban Development and Poverty Alleviation. Specific attention to socially marginalised groups comes within the remit of three more separate ministries, i.e. Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Ministry of Tribal Affairs and Ministry of Minority Affairs. This requires a tremendous effort at coordination. Achieving positive nutrition outcomes is therefore contingent upon effective coordination between these ministries.

In order for nutrition problems to be addressed effectively, India may well need a Nutrition Mission that has the authority and system to coordinate an integrated approach between the myriad of actors implementing nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive programming and holds various stakeholders, including government, to account for actions and inaction.

For more information, contact: Ajay Kumar Sinha, email: ajay.s@flairindia.org C-102, J. M. Orchid, Sector 76, Noida – 201301, U.P., India. Website: www.flairindia.org Email: info@flairindia.org

1The Global Hunger Index (GHI) is designed to comprehensively measure and track hunger globally and by country and region. It is calculated each year by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). The GHI ranks countries on a 100-point scale. Zero is the best score (no hunger), and 100 is the worst, although neither of these extremes is reached in practice. Visit http://www.ifpri.org/

2 Weight for age <-2 SD. This data is for children under 5 years of age and is provisional as reported by the Global Hunger Index (GHI), see: http://www.ifpri.org/sites/default/files/publications/ghi14factsasia.pdf

3Levels and trends in Child Mortality, Report 2013, by UNICEF

4GHI, The challenge of Hidden Hunger, 2014

5NFHS-3 uses NCHS references, while DLHS 4 and CNSM (cited later) use WHO Growth Standards.

6District Level Household and Facility Survey (DLHS), round IV, 2012-2013

7 For example, Comprehensive Nutrition Survey in Maharashtra, CNSM 2012, http://www.iipsindia.org/pdf/CNSMFACTSHEET%20-%202012.pdf

8Annual Project Implementation Plan, 2012-2013, ICDS, Dept of Women and Child Development, Government of Maharashtra

9 DLHS III 2007-08

10 NFHS III

11 Two common parasitic infections are Giardia Lamblia and Hookworm infection.

12 Toteja GS, Singh P. Micronutrient profile of Indian population New Delhi: Indian Council of Medical Research; 2004

13 DLHS III

14 Black, Robert E., and others, ‘Maternal and Child Undernutrition: Global and Regional Exposures and Health Consequences’, The Lancet, vol. 371, no. 9608, 19 January 2008, pp. 243–260.

15 NFHS 3 (2005-06), Vol. I September 207, (http://www.rchiips.org/nfhs/NFHS-3 Data/VOL-1/India_volume_I_corrected_17oct08.pdf

16 WHO recommended IYCF practices are: Breastfed children of 6-23 months to be fed three or more food groups daily and a minimum number of times according to age (twice a day for 6-8 months and at least 3-times a day for 9-23 months); Non-breastfed children aged 6-23 months to be fed milk or milk products, at least four or more food groups, and four or more times a day.

17Ibid

18 Hunger, Under-Nutrition and Food Security in India, N C Saxena, IIPA, New Delhi, 2011

19 69th round NSSO survey report on drinking water, sanitation, hygiene and housing condition in India

21 The Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) are official designations given to various groups of historically disadvantaged people. The terms are recognised in the Constitution of India and the various groups are designated in one or other of the categories. During the period of British rule in the Indian subcontinent, they were known as the Depressed Classes. In modern literature, the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled tribes are referred to as Dalits and Adivasis respectively. SCs and STs have been among the most disadvantaged sections of our society due to their socio-economic exploitation and isolation over a long period of time.

22National Sample Survey Organisation. Nutrition Intake in India 2011-12, Report No. 560, NSS 68th Round (July 2011 - June 2012)

23 ICDS is the programme initiated with increased emphasis on the provision of supplementary feeding and preschool education to children of 3-6 years.

24 initiated to provide a cooked meal with 300 calories and 8-12 grams of protein to the school children

25 As of now, 34 countries have signed Convention on the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

26 Ajay Kumar Sinha and Dolon Bhattacharyya, Budget analysis of Food and Nutrition Programmes in India, FLAIR, 2015

27 All schemes taken from Detailed Demand for Grants, Government of India, and various Ministries; those relevant are footnoted in Table 3.

28 Crore is equivalent to 10,000,000 rupees or 1,00,00,000 in the Indian system

29Ibid

30 As per census 2011, share of SCs and STs in total population calculated as 17% and 9% respectively

31 Ajay Kumar Sinha and Dolon Bhattacharyya, Child Under-Nutrition and Public Finance for Food and Nutrition Security, FLAIR WORKING PAPER – NUTRITION FINANCE (version3), June 2015 (http://www.flairindia.org/documents&reports/discussion_paper/Health%20and%20nutrition/FLAIR_working_Paper_Version%203_Policy_and_Budget_for_food_and_nutrition.pdf)

32Ibid

33 Utilisation Certificates are sent by State Governments to the Union Government for the release of funds for the next quarter. These are essentially financial reports showing usage of funds.

English

English Français

Français Deutsch

Deutsch Italiano

Italiano Español

Español