Briefing on the Bihar Child Support Programme, India

By Oxford Policy Management (OPM) India

By Oxford Policy Management (OPM) India

Oxford Policy Management (OPM) is a development and research based consultancy company that has 30 years’ experience is providing rigorous analysis, policy advice, management and training services to national governments, international aid agencies and other public sector and non-government organisations. OPM works across the policy cycle, including formative research and analysis, diagnostic and design work, strategic implementation support, the development of monitoring systems, and operational, process, programme and impact evaluations). In India, OPM has a full time office in Delhi and six states.

Oxford Policy Management (OPM)’s India office has supported the Government of Bihar to design, pilot and evaluate the Bihar Child Support Programme.

The Bihar Child Support Programme is implemented by the Social Welfare Department, Government of Bihar and funded by the Department for International Development (DFID). It is supported through the Bihar Technical Assistance and Support Team (BTAST) and by Oxford Policy Management.

Location: Bihar, India

What we know: There is limited evidence within India of the impact of conditional cash transfers on nutrition outcomes. Existing schemes have implementation challenges.

What this article adds:

The Bihar Child Support Programme is a pilot conditional cash transfer (CCT) within the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) Scheme introduced in Gaya District to test the viability and effectiveness of a CCT aimed at improving child nutrition outcomes. Women are registered at the end of the first trimester of pregnancy and are eligible to receive INR 250 per month until their child is three years old if certain conditions are met; bonus payments are possible (for birth spacing and child wasting outcomes). A mixed-methods impact evaluation will generate evidence on effectiveness, impact and relative cost-effectiveness. Operational reviews and monitoring data to date have found robust payment systems and indicate improvements in staff and beneficiary attendance, growth monitoring and ORS use. Impact evaluation results will be available in April 2016.

This article provides an overview of the Bihar Child Support Programme (BCSP), a pilot experiment that tests whether a CCT aimed at pregnant women and mothers of young children can help improve child nutrition outcomes. It is being piloted by the Social Welfare Department of the Government of Bihar in 261 Anganwadi centres. Findings will support the Government’s consideration of scale-up in Bihar and may also help in strengthening existing centrally and state-funded CCT programmes. The sections below discuss the context for the programme, the programme objectives, the implementation design, the evaluation strategy and current project status, as well as the next steps.

The context

In recent years there has been immense interest in Bihar in combating child malnutrition. Child malnutrition rates in the state have declined over the past decade but remain high in absolute terms. The Office of the Registrar General has been conducting Annual Health Surveys for the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare since 2010. The clinical, anthropometric and biochemical (CAB) Survey conducted in 2014 to supplement the Annual Health Surveys (Office of the Registrar General, 2010) found that 40.3% of children under five years of age were underweight, 52% were stunted and 19.2% were wasted. The provisional results of the Rapid Survey on Children 2013-2014 released by the Ministry of Women and Child Development show that these figures for children under three years of age in Bihar were 37%, 49% and 13%, respectively. Despite the decline, the rates of child malnutrition are still very high in absolute terms. This is not a problem peculiar to Bihar; malnutrition rates across all of south Asia are stubbornly high, and higher than much poorer countries in sub-Saharan Africa. This is acknowledged to be the ‘South Asian enigma’.

In Bihar, and across India, CCTs have been suggested as a potential policy instrument to address this problem, based on promising global experience (Lagarde, Haines & Palmer, 2009; Manley, Manley, Gitter, & Slavchevska, 2012). However, there is a limited evidence base within India of the potential merits of cash transfers. Therefore, there was need for pilot projects such as the Bihar Child Support Programme (BCSP), a CCT within the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) Scheme in Bihar aimed at improving child nutrition outcomes. It is hoped that this pilot can provide rigorous evidence of the potential effectiveness and value for money of cash transfers and help inform the debate at national and state levels. The BCSP is also an opportunity to develop a ‘ best-practice’ standard of cash transfer implementation that can be a beacon to all other schemes, using cutting-edge technology. It was introduced to test a) the viability and b) the effectiveness of a CCT on child nutrition outcomes.

About the Bihar Child Support Programme

The BCSP is being implemented in two blocks in Gaya District. It began with a pre-pilot programme in August 2013, followed by implementation of the pilot, which began in September 2014 and will continue until at least April 2016.

The pilot is testing two things:

- Viability: Is it feasible for the State Government to implement on a reasonable scale the high-quality systems required to deliver a monthly CCT in a way that is realistically scalable and sustainable?

- Impact: As a policy instrument, does a CCT have a significant impact on the uptake of ICDS services and adherence to nutrition-sensitive behaviours, and is this sufficient to improve child nutrition outcomes?

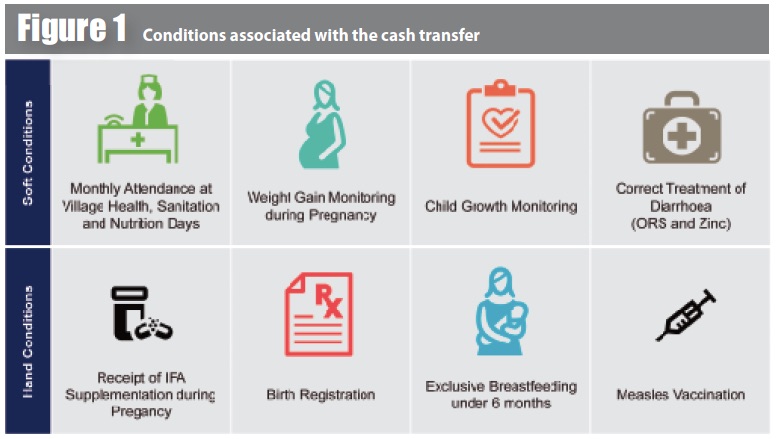

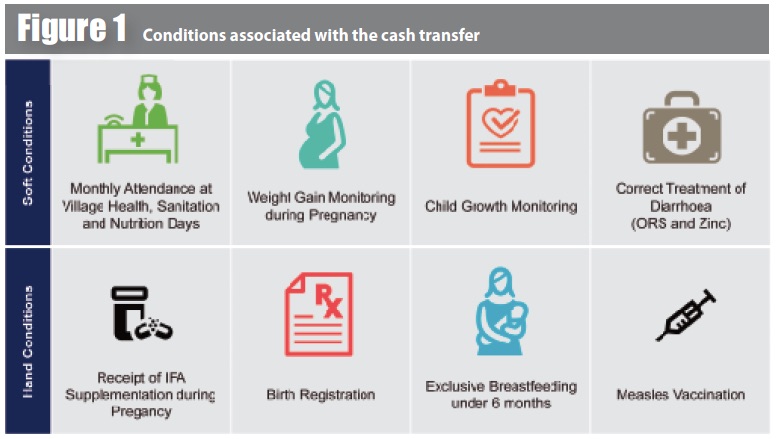

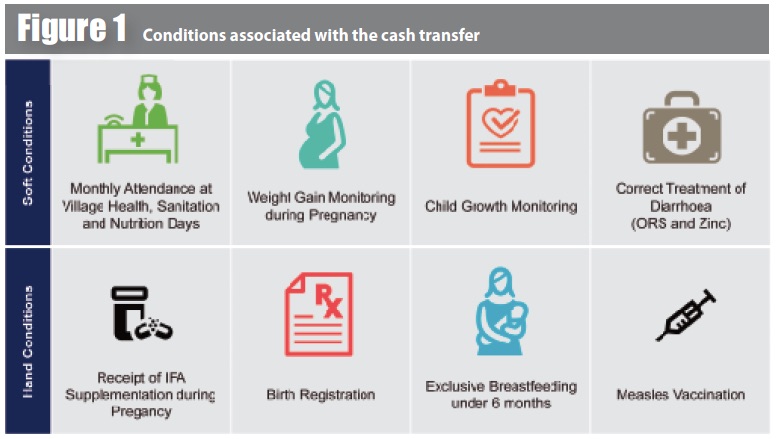

Under the BCSP, women are registered at the end of the first trimester of pregnancy and are eligible to receive INR 250 per month until the child is three years old (i.e. for a total of 42 months). This was calculated to be one third of household monthly consumption expenditure on food. Women receive the money only if they meet certain conditions (see Figure 1). The conditions relate to the uptake of government-provided community nutrition services (through monthly Village Health and Nutrition Days) and certain pro-nutrition behaviours.

IFA: Iron Folic Acid

The pilot is set up to test different configurations of conditions to help understand which are most amenable to change as a result of a CCT. There is also a set of bonuses when a child turns two and three years old if a mother has not become pregnant again (to promote birth spacing) in one configuration, and if a child is not underweight (to promote mothers to undertake other complementary actions to promote positive outcomes). In total, a mother can receive up to INR 15,500 conditional on meeting all conditions throughout the duration of her programme enrolment.

The Anganwadi centre worker is responsible for registering beneficiaries and recording their adherence to conditions, using a customised mobile phone application. Data are transmitted to a server, which generates payment lists. Payment lists are reviewed and approved by the Child Development Project Officer (CDPO) and District Programme Officer (DPO). Funds for the programme are held in the DPO’s official bank account and an instruction is given to the bank to execute the payments, which are made through direct bank transfers using National Electronic Funds Transfer (NEFT). The State Government transfers funds in advance to the DPO based on utilisation certificates of previous expenditure. This ensures that cash is delivered on time (within 20 days of the end of the month), leakages and fraud are minimised through using banks’ own systems of verification for enrolment and withdrawal, and transaction costs are kept low. The process is summarised in Figure 2.

Roles and responsibilities

The BCSP aims to support and strengthen ICDS service delivery. Anganwadi centre workers are at the centre of the BCSP, since they register beneficiaries and record adherence to conditions. In turn, the conditions support the effectiveness of the workers by increasing demand for their services and counselling. A Community Monitoring Group (normally an existing self-help group) is engaged to ensure full enrolment, accurate data recording and effective grievance redress. Female supervisors monitor the performance of Anganwadi workers, facilitated by the Management Information Systems (MIS) data generated by the project. CDPOs review programme performance and verify payment lists at the block level. The DPO reviews programme performance and verifies payment lists at the district level and executes payment instructions to the bank. Project staff have been engaged on a temporary basis to support the CDPOs and DPO in their roles. The State Government has an overall oversight role and transfers funds to the DPO quarterly.

Evaluating impact

A mixed-methods impact evaluation is being undertaken alongside the pilot to generate evidence on the questions of effectiveness, impact and relative cost-effectiveness outlined above. A baseline population survey covering 6,600 households was undertaken in 2013 and a quantitative midline survey was completed in September 2015; these will be complemented by two qualitative studies (results will be available in April 2016).

The quantitative evaluation uses a quasi-experimental design, comparing blocks receiving treatment with matched blocks not receiving treatment. A separate block just receiving the technology underpinning the cash transfer is also included for evaluation purposes to see the relative importance of this compared to the demand-side incentive, as it is likely to independently improve outcomes through supply-side improvements.

The impact evaluation primarily seeks to ascertain whether there has been any change in the value of the evaluation indicators as a result of the BCSP monthly cash transfer. The impact evaluation is meant to be based on measuring these indicators both before the introduction of the BCSP monthly cash transfer (the baseline) and after its introduction. The end line, and changes in the value of the indicators in the treatment and control groups, will then be compared; this is a difference-in-differences approach.

The baseline and midline surveys were conducted in four selected blocks: two treatment blocks, one control block, and one pure control block.

- Pure control block: where there is no cash transfer or mobile phone application to improve service delivery;

- Control block (with technology system): where there is no cash transfer but the Anganwadi workers will be using the mobile phone application to improve service delivery;

- Treatment block 1 (Wazirganj): where there is cash transfer conditional upon soft conditions; and

- Treatment block 2 (Atri): where there is cash transfer conditional upon hard conditions.

The potential ‘pathways to impact’ that the BCSP may have, which will be tested through the evaluation, include:

- A resource effect: whether the additional household income received due to the BCSP is translated into increased expenditure on food (and more nutritious food), healthcare and other pro-nutrition expenditures;

- An empowerment effect: whether the fact that the cash is transferred to the women improves her status within the household and her decision-making power, control over resources, and time use;

- An incentive effect: whether beneficiaries change their behaviours and seek out available services in order to receive the money; and

- A social accountability effect: whether beneficiaries pressure service providers to improve the accessibility and quality of services to enable them to meet the conditions.

The theory of change is summarised in Figure 3. Child nutrition outcomes, in addition to a whole range of output and outcome indicators, will be measured and compared across the four blocks.

Current status and findings

The BCSP started as a pre-pilot across ten Anganwadi centres in Sahora Gram Panchayat in August 2013 to test the implementation systems and was scaled up across two blocks, Atri and Wazirganj, in September 2014, covering 261 Anganwadi centres. A total of 6,095 beneficiaries were enrolled by the end of August 2015; approximately 81% of eligible beneficiaries across the two blocks were enrolled. The remaining 19% include: the population covered by non-functional Anganwadi centres; those who migrate out for long periods of time (e.g. to brick kilns); those who were not interested in the scheme; and those who were unable to open bank accounts (consequently, the programme implementation team is facilitating account opening).

By the end of November 2015, a total of 7,504 beneficiaries were registered and 74% of them met their conditions and received payment. Payments initially suffered from delays and a high number of bounced-back payments (up to 18%), due to errors in transcription of bank account details, dormant accounts, and an inability of some rural bank branches to receive NEFT payments. With field-based support to check bounced-back payments, this was relatively easily solved, with bounced-back payments now under 1% of total payments and payment times down to under three weeks.

By the end of November 2015, a total of 7,504 beneficiaries were registered and 74% of them met their conditions and received payment. Payments initially suffered from delays and a high number of bounced-back payments (up to 18%), due to errors in transcription of bank account details, dormant accounts, and an inability of some rural bank branches to receive NEFT payments. With field-based support to check bounced-back payments, this was relatively easily solved, with bounced-back payments now under 1% of total payments and payment times down to under three weeks.

In general, the systems underpinning the CCT have been found to be robust. This is supported by a formal operational review of the programme that was undertaken in March to April 2015 for the period up to March 2015. MIS data suggests that:

- There has been a steady increase in the number of Village Health, Sanitation and Nutrition Days (VHSNDs) held across the programme area;

- The attendance of Auxillary Nurse Midwives (ANMs) and Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) and stock availability has improved considerably at VHSNDs; and

- This has translated into increased attendance, higher rates of pregnancy weight-gain monitoring, child-growth monitoring and greater receipt of IFA tablets by pregnant women.

Next steps

The formal impact evaluation of the BCSP entails a midline survey which was recently conducted in the August to September 2015 period in conjunction with two qualitative assessments. Further, a second follow-up operational review will be undertaken in 2016 to review the evolving and dynamic programme aspects. The evaluation population will include a range of stakeholders encompassing programme beneficiaries, ICDS functionaries (including Anganwadi centre workers), government officials, project implementation staff and banking correspondents.

The impact evaluation report will be finalised by April 2016 and summarised in a future edition of Field Exchange. It will enable understanding of the impact of the pilot programme and inform any decision to scale up. It is hoped that the systems learning can be applied to other similar schemes, such as Indira Gandhi Matritva Sahyog Yojana (IGMSY), a maternity benefit programme introduced in 2010 by the Government.

For further information, please contact Tom Newton-Lewis.

References

Lagarde, M., Haines, A., & Palmer, N. (2009). The impact of conditional cash transfers on health outcomes and use of health services in low and middle income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 4(4).

Manley, J., Gitter, S., & Slavchevska, V. (2012). How effective are cash transfer programmes at improving nutritional status? A rapid evidence assessment of programmes’ effects on anthropometric outcomes. London EPPI Centre. Social Research Science Unit. Institute of Education. London: University of London.

The Office of the Registrar General, India, 2010. CAB Survey factsheets www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/hh-series/cab.html?