Child Development Grant Programme (CDGP) in northern Nigeria: influencing nutrition-sensitive social policy programming in Jigawa State

By Fatima Adamu, Maureen Gallagher and Paul Xavier Thangarasa

Fatima Adamu is the Communication Officer for Action Against Hunger Nigeria’s Child Development Grant Programme (CDGP), based in Jigawa State. Her previous experience includes working on maternal and child health programmes and on social protection in Nigeria.

Maureen Gallagher is the Senior Nutrition & Health Advisor Action Against Hunger USA, based in New York. She is a public health specialist with an MSc in Social Policy and Planning, specialising in health policy. She has been working in nutrition programming for the last 15 years in Niger, East Timor, Uganda, Chad, DRC, Burma, Sudan and Nigeria.

Paul Antony Xavier Thangarasa is the Social Protection Programme Manager for the Action Against Hunger Nigeria Mission, based in Abuja. He has an MSc in Disaster Management. He has worked in food security, livelihood and social protection programmes for the last ten years in Sri Lanka, Pakistan, South Sudan, Philippines and Nigeria.

The authors would like to thank the Government of Nigeria at federal, state and local government levels as well as partners, particularly Save the Children, for their collaboration in fighting undernutrition in Nigeria, particularly with their work in the CDGP programme. Thanks also to Action Against Hunger field teams in Jigawa State for their hard work and commitment to the programme. Thank you to Julien Morel and Melanie Roberts for their contributions to the article. Finally, the authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of the Department for International Development (UK AID) for their support to nutrition-sensitive programming in northern Nigeria.

Location: Nigeria

What we know: Despite an annual growth rate of 6.6%, acute and chronic malnutrition are prevalent in Nigeria, associated with poverty and inequality. Political will supports social protection to address poverty but investment remains low.

What this article adds: The Child Development Grant Programme is a five-year programme in Jigawa State and Zamfara State that involves a monthly, unconditional cash grant coupled with behaviour change communication (BCC) to address maternal education, healthcare facility access, improved household economic status, infant feeding, food consumption and women’s empowerment. Implemented by Action Against Hunger (Jigawa) and Save the Children (Zamfara), it targets women through pregnancy and until the child reaches two years of age. Key multi-sectoral practices are the basis for behaviour change. The CDGP includes nutrition-sensitive objectives, targets the full 1,000 days, integrates a robust monitoring and evaluation (M&E) system, prioritises women’s empowerment, and includes an independent research component. Final outcome analysis will be available in 2017; improvements in antenatal attendance are already being observed. Findings will inform nutrition-sensitive social protection policies and schemes in Nigeria.

With a population of approximately 170 million people, Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa. It is the 12th largest producer/exporter of petroleum worldwide with an annual Gross Domestic Product of USD262.6 billion in 2013 (World Bank, 2013) and an annual growth rate of around 6.6% (National Health Demographic Survey, 2014). Despite this, it has one of the highest numbers of people living in poverty and inequality. National prevalence of global acute malnutrition (GAM) is estimated at 7.2% with severe acute malnutrition (SAM) at 1.8% (SMART Survey 2015).

With a population of approximately 170 million people, Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa. It is the 12th largest producer/exporter of petroleum worldwide with an annual Gross Domestic Product of USD262.6 billion in 2013 (World Bank, 2013) and an annual growth rate of around 6.6% (National Health Demographic Survey, 2014). Despite this, it has one of the highest numbers of people living in poverty and inequality. National prevalence of global acute malnutrition (GAM) is estimated at 7.2% with severe acute malnutrition (SAM) at 1.8% (SMART Survey 2015).

Action Against Hunger (AAH) has operated in north-eastern Nigeria since early 2011, focused on nutrition, water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) and food security, working closely with UNICEF and Save the Children. In 2013, the Child Development Grant Programme (CDGP) was developed by a consortium led by Save the Children with AAH in order to pilot and build evidence on social protection schemes in Nigeria and their specific impact on undernutrition and the first 1,000 days. It is hoped that this five-year programme will lead to further development of nutrition-sensitive social protection policies and schemes in Nigeria. The programme is being implemented in Jigawa (AAH) and Zamfara (Save the Children) states. This article focuses on the Jigawa State context and activities and includes excerpts from a case study produced by the Cash Learning Project (CaLP) (Trousseau, 2014).

Project context

Acute undernutrition is the major contributor to death of children under five years old. In northern Nigeria, half of all children under five are stunted and one in ten suffers from acute undernutrition. Jigawa State has a GAM of 11.9% (9.5-14.9%), with reported prevalence of SAM of 1.7% (0.9-3.4%) (SMART, 2015). Nutritional status is influenced by factors related to food, health and care. Household food production in the north-west region covers on average less than 20% of household’s needs (Kuku-Shittu, Mathiassen, Wadhwa et al, 2013). Children are directly affected by limited food access in terms of quantity and quality. Other contributing factors include the absence of skilled health workers and husband’s disapproval of the use of health services by family members (UNICEF, 2013)

Social policy context1

The Government of Nigeria with support from development partners has identified social protection as a tool to tackle the country’s high rate of poverty, yet investment remains low. Social protection has been on the Nigerian policy agenda since 2004, when the National Planning Commission (NPC), supported by the international community, drafted the first social protection strategy. Since 2004, the strategy has generated limited political traction, despite a chapter dedicated in Nigeria’s most recent national policy implementation: Nigeria Vision 20:2020 (Holmes, Akintimisi, Morgan et al, 2011). Social protection schemes are estimated to cover less than 0.02% of the poor at country level and impact is affected by short-term participation and low transfer value. There has been some progress with the recent appointment of a special advisor on social protection to the Vice President, who is working closely with the NPC to move the policy forward. DFID is also following this closely, as the World Bank and President Buhari’s Government has pledged for specific funding in 2016 (See Figure 1). Most recent revisions have included specific services for internally displaced people. Presently, social protection programmes are implemented ad hoc in various parts of the country by the federal and state governments under different ministries and agencies (see Box 1 for examples). The absence of a finalised policy on social protection at the federal level is a major constraint for effective social protection programming in Jigawa State. Nonetheless, several programmes are run at individual ministry and agency level without a state coordinating body.

Box 1: Social protection programmes in Nigeria2

The Conditional Cash Transfer in Care of People funded by the office of the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) targets poor, female-headed households with members who are elderly, physically challenged, HIV/AIDS patients, and with children of school age. Beneficiaries receive 12 monthly payments of USD10 per child with USD33 cap for households with four or more children. Conditions attached include enrolment of children in basic education, participation in free healthcare programme and attending business and life-skills training.

The Maternal and Child Health care programme is a health-fee waiver for pregnant women and children under five implemented by the office of the Senior Special Assistant to the President on MDG in collaboration with the National Health Insurance Scheme. This is only implemented in selected states and coverage within areas of implementation is not 100%.

A community-based health insurance scheme implemented in several states (Holmes et al, 2012).

Box 2. Social protection programmes in Jigawa State

Social protection schemes in Jigawa State include:

Social protection schemes in Jigawa State include:

Social Security programme for the physically challenged and the disabled: Since 2007, this falls under the Directorate of Rehabilitation Board under the Ministry of Women Affairs and Social Development. Covers 50,000 families across 27 local government areas. Provides 7,000 Naira (about USD35) monthly to Ministry of Health (MoH)-assessed individuals. Disabled children included through access to education and proper health services.

Safe Motherhood Initiative: Under the Ministry of Women Affairs. Provides mobile clinics for safe delivery to address maternal health gaps in rural communities.

Free Girl Child education for girls: For children with disabilities; provides scholarship for students in higher institution of learning.

Women in agriculture programme: Run by the Ministry of Agriculture; provides fertilisers and seedling subsidies.

Women’s empowerment initiative: Widows are given three goats (one male, two female). Female local food vendors are given 10,000 Naira (USD50) to boost business.

In Jigawa State, social protection programming has been a priority with funding of schemes prioritised over civil servants’ payments. Through collaboration of some international non-governmental organisations and the Food and Nutrition Committee, a Food and Nutrition policy is under development to address child-related concerns which will be informed by the CDGP pilot project. However, despite the political will and previous achievements, there is still some way to go towards finalising and achieving a state policy on social protection.

The CDGP consortium is currently closely working with State Governments through the State Steering Committees (SSC) for the adaptation of the draft National Social Protection Policy to define a state-focused/state-specific social protection policy. This aims to generate political commitment and funding for social protection programmes and to establish a sustainable coordination mechanism for social protection interventions. CDGP had recently facilitated a presentation for the key members of the SSC on setting the context for social protection policy, supported by the Sector Lead for Social Protection from the Federal Ministry of Budget and National Planning. Jigawa State is planning to domesticate the National Social Protection Policy after it has been passed into a law and, at the same time, the SSC for CDGP has shown commitment to develop a state policy on social protection if the National Social Protection Policy is further delayed in becoming law.

CDGB in Jigawa State

In Jigawa, CDGP is being implemented in three local government areas (LGAs) (equivalent to district and county administrative units in other countries): Buji, Gagarawa and Kirkassamma. It provides unconditional monthly cash transfers of 3,500 Naira (USD12) to 30,000 pregnant women in Jigawa State through pregnancy and until the child reaches the age of two. The transfer is accompanied by nutritional advice and counselling. The programme vision is to produce evidence of impact and ensure the takeover of the programme – with eventual scale-up – by the Government in the intervention states. The combination of cash transfers and BCC is geared to be more politically acceptable by State Governments’ stakeholders than standalone unconditional cash transfers; many actors fear the latter may be used for expenditures that do not serve the programme purposes. It is also expected to serve as a model for nutrition-sensitive social protection programmes and pave the way for other state and federal level social protection schemes. It includes a government contribution-tracking tool that will help calculate the monetary value of the State and LGA contribution to the programme. The assumption is that demonstrating nutrition impact on mothers and children will generate long-term government buy-in. However, more work is needed on estimating costs for a sustainable government-funded and led scheme.

The CDGP outputs are:

- Secure payment mechanisms providing regular, timely cash transfers;

- Effective systems for mobilisation and complementary interventions, including BCC;

- Enhanced government capacities for managing cash transfer in target states; and

- Evidence of impact provided to policy-makers.

Since April 2014, 14,960 pregnant women have been registered on the programme and as of September 2015, 13,065 beneficiaries had received payment in Jigawa State. A complaints and response mechanism is in place that includes involvement of community-level committees (Beneficiary Reference Groups) as well as LGA officials.

The nutrition-sensitive component of the CDGP follows the following principles (reflecting the recommendations of the ACF’s Nutrition Security Policy):

- Includes nutritional-specific objective and indicators;

- Focuses on the most nutritionally vulnerable population and areas;

- Considers potential negative impacts on undernutrition and how to mitigate these;

- Is of adequate duration and timeliness to influence nutritional status of children (1,000 days);

- Monitors nutritional effects and outcomes;

- Empowers women, and considers women’s time allocation; and

- Includes nutrition promotion and behaviour change strategies.

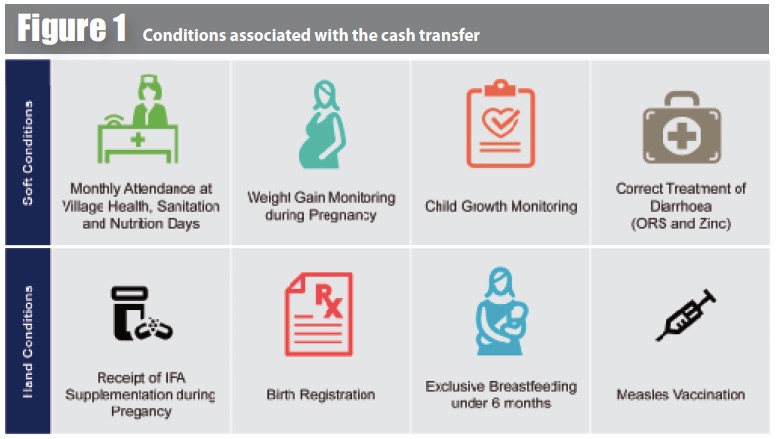

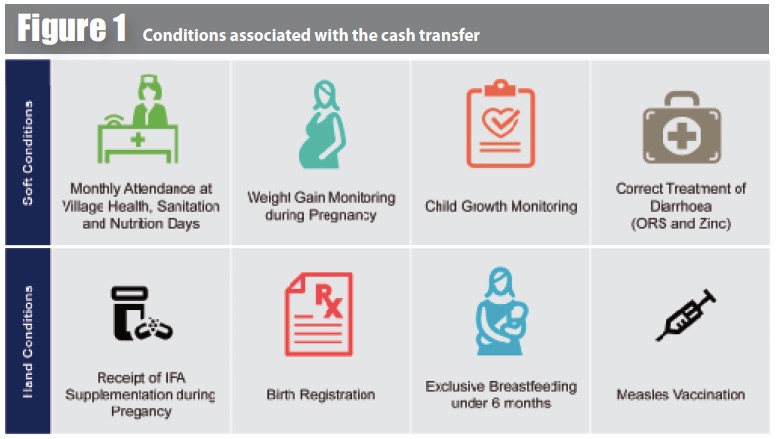

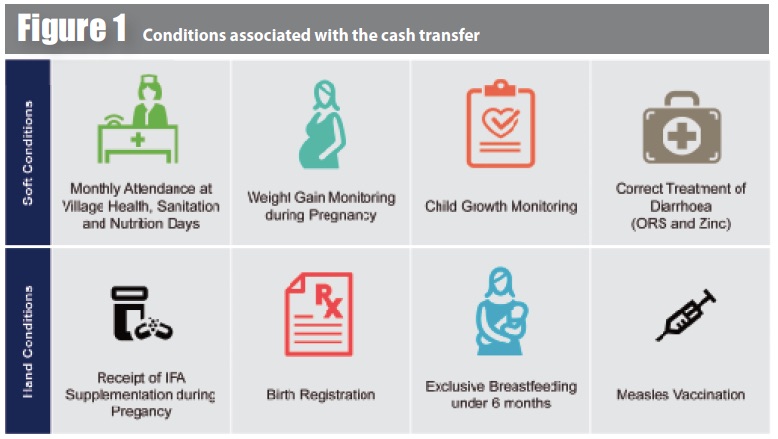

A set of key practices is the basis for promoting improved behaviours amongst beneficiaries, as seen in Box 3 (Holmes et al, 2011). The design reflects the multi-sectoral nature of the project in bringing together better nutrition, health, food security, and hygiene practices. The cash mechanism provides flexibility for caregivers to have better access to services for children, such as education and health services. In some cases, caregivers engage in economic activities as shared by one beneficiary in Box 4. The main aim of the programme remains in food and nutrition security of households.

Box 3: Key nutritional behaviours promoted as part of the CDGP programme

- Mothers to eat one additional meal each day during pregnancy.

- Attend antenatal care at least four times during pregnancy.

- Place the newborn on the breast within 30 minutes of delivery (early initiation)

- Do not offer pre-lacteal feeds to your baby.

- Practice exclusive breastfeeding (from birth to six months of age) – no water, no breastmilk substitute.

- Introduce complementary foods at six months of age (180 days) while continuing to breastfeed.

- Use good hygiene practices (three practices – wash hands with soap before food preparation, wash your hands and the child’s before and after feeding baby/child, wash hands each time after using toilet or cleaning baby’s bottom).

- Purchase healthy/nutritious foods for your family.

- Feed your child a variety of foods and increase that variety as the child gets older.

Box 4: Beneficiary testimony on improved access to health, education services and economic empowerment

Hadiza, a beneficiary in Gagarawa LGA:

“From the money, I buy food and nutritious meals for my family. Also, through saving which I do with other women in the programme, I have been able to treat myself in the hospital because I have high blood pressure. Before the programme my husband and I found it difficult to pay fees for my children’s education but now I can do that. I have even bought a bicycle for my son to use as means of transport to school because his school is far from the house and I have also started awara business, selling soya bean cake.”

State engagement and advocacy3

A Political Economy Analysis (PEA) was conducted in 2014 at the inception of the programme to capture the political enabling and constraining factors. Findings will influence the state engagement strategy that is currently being developed (Zasha & Magaji, 2014). The work of ministries and department agencies on social protection and child nutrition are key existing opportunities in the State. The Ministries of Women’s Affairs and Social Development, the Rehabilitation Board and the MoH are all champions of social protection and child nutrition programming. More importantly, there is a body of multi-sector experience in policy development in Jigawa State exemplified in the gender mainstreaming in policies of the Ministries of Education, Health, Environment, Water Resources and Women Affairs and Social Development. One major constraint is the lack of coordination in the execution of state social protection programmes; there is also no coherent framework or policy that initiatives can draw upon. This makes for a less cost-effective and cost-efficient service delivery platform for beneficiaries. Furthermore, with the change in the governing party in Jigawa State, there may be a need to conduct a new PEA.

A Political Economy Analysis (PEA) was conducted in 2014 at the inception of the programme to capture the political enabling and constraining factors. Findings will influence the state engagement strategy that is currently being developed (Zasha & Magaji, 2014). The work of ministries and department agencies on social protection and child nutrition are key existing opportunities in the State. The Ministries of Women’s Affairs and Social Development, the Rehabilitation Board and the MoH are all champions of social protection and child nutrition programming. More importantly, there is a body of multi-sector experience in policy development in Jigawa State exemplified in the gender mainstreaming in policies of the Ministries of Education, Health, Environment, Water Resources and Women Affairs and Social Development. One major constraint is the lack of coordination in the execution of state social protection programmes; there is also no coherent framework or policy that initiatives can draw upon. This makes for a less cost-effective and cost-efficient service delivery platform for beneficiaries. Furthermore, with the change in the governing party in Jigawa State, there may be a need to conduct a new PEA.

The government of Jigawa State is progressive with regards to social protection and willing to implement such programmes. This is reflected in a recent request for an impact assessment to be carried out on the cash transfer programme for people with disabilities funded by the state and also the women empowerment initiatives (see Box 2). The Ministry of Local Government & Chieftaincy Affairs is responsible for supervising, monitoring and coordinating the activities of the Local Government councils in the State and in Jigawa, is the focal agency for social protection programming. The selection of the hosting Ministry was based on four criteria:

- The capacity to facilitate government support in the development of Social Protection Policy;

- The capacity to provide sustainability and support government takeover of the programme;

- The provision of personnel and funds to support programme implementation;

- The technical and political capacity for institutionalisation of the programme.

Other key stakeholders such as the Directorate for Budget and Economic Planning, and Ministries of Health, Women Affairs and Social Development, will constitute a committee that will help by financing social protection programmes and implementing schemes like the CDGP.

Since inception, state government, local government and traditional leaders have been involved in programme management through a three-tier system of committees. These are the SSC (programme oversight); LGA Technical Working committee (implementation support); and the Traditional Ward Committee comprising traditional leaders in the communities (community-level implementation). Activities aimed at informing and mobilising state, LGA and community stakeholders were conducted from the early stages of the programme with the support of the SSC.

Project impact on undernutrition

The CDGP is being evaluated by an external partner, ePACT. The key nutritional outcome indicators to be measured at baseline and endline and the targets are presented in Table 1. Key features of the monitoring plan include:

- Baseline (qualitative and quantitative) – 2014;

- Midline (process monitoring) – 2016;

- Endline (qualitative and quantitative) – 2017; and

- Quarterly and bi-annual post distribution monitoring (PDMs).

Positive results for some key health-seeking behaviours are already noted; 55% of pregnant women beneficiaries attend antenatal care in Jigawa (45% baseline) (CDGP, 2015). In relation to the nutrition and food security aim of the project, the same report revealed that nearly all (99%) of beneficiaries ticked food as one of the items they spent money on. Thirty-nine per cent of respondents solely spend the cash transfer on purchase of food and food-related items (CDGP, 2015).

* CDGP Logframe; no state specific baseline information is available.

Lessons learned

-

Elements to consider in designing a nutrition-sensitive intervention

Key components to consider when designing a nutrition-sensitive approach include defining nutrition sensitive objectives, targeting the full 1,000 days for better impact, integrating a robust monitoring and evaluation system, and prioritising women’s empowerment. There is value in including an independent research component to strengthen capacity to produce evidence to influence national and state nutrition-sensitive social protection policies.

-

Nutrition and BCC

The nutrition component is very dependent on the work of community volunteers. The complementary nutrition and health BCC can be strengthened with the cash disbursement. A wider range of activities that involve more time with the beneficiaries are required in order for behaviours to be adopted by women enrolled in the scheme.

-

Roles and responsibilities

At the end of the inception phase, the involvement of the hosting ministry resulted in the provision of staff and facilities by local governments. Seconded staff have been provided and a counter-funding mechanism for the payment of secondees is already in place. This is expected to play an important role in programme sustainability and to help scale-up.

-

Importance of multi-sector collaboration

Close collaboration with other agencies and state ministries that are not directly linked with the programme is needed. So far, CDGP has worked with the NPC and National Identity Management Commission to ensure that beneficiaries are presented with birth certificates and appropriate identification mechanism; a practice which is not common in the northern part of the country that will improve the quality of national data.

Working closely with MoH, especially with the Gunduma Health System Board (GHSB), has facilitated an increased number of health workers in facilities in CDGB areas. CDGP relies on the health workers and Community Health Extension Workers (CHEWs) for verification of beneficiaries’ pregnancy and health education. The GHSB provided ten CHEWs per LGA to contribute approximately 20% of their time to CDGP as a result of continuous sensitisation by the programme. This will support women’s antenatal care attendance and behaviours for improved child nutrition and survival. In turn, it may also be a motivating factor for health workers in seeing that as a result of BCC, more women are seeking services.

Conclusion

Despite challenges, the CDGP looks to provide women with more flexibility in access and choice on where to invest resources towards improved nutrition and food security, including improved health and education. Impact on antenatal care attendance and food access is already indicated. The final outcome analysis will be available in 2017, as the ‘first generation’ of children will have graduated from the project by the latter part of 2016.

For more information, contact Maureen Gallagher

Footnotes

1 Based on the case study produced by the Cash Learning Project (CaLP). (Trousseau, 2014)

2 Based on summary from CaLP.

3 Excerpt from CaLP.

References

CDGP (2015). Post-Distribution Monitoring report.

Holmes, R. et al (2011); Social protection in Nigeria: an overview of programmes and their effectiveness. ODI Project Briefing No 59.

Holmes, R., Akintimisi, B., Morgan, J. & Buck, R. (2012). Social Protection in Nigeria. ODI Research project

Kuku-Shittu, O., Mathiassen, A., Wadhwa, A., Myles, L. & Ajibola, A. (2013). Comprehensive Food Security and Vulnerability Analysis – Nigeria.

National Health Demographic Survey (2014).

SMART survey (2015).

Trousseau (2014). Planning for government adoption of a social protection programme in an insecure environment: The Child Grant Development Programme in northern Nigeria. Save the Children and ACF retrieved from www.cmamforum.org

UNICEF (2013). Improving Child Nutrition, the achievable imperative for global progress.

World Bank (2013). Annual report 2013. www.worldbank.org as cited in Nigeria National Demographic Health Survey (2014) p.2.

Zasha, J. & Magaji, B. (2014) Political Economy Study for Child Development Grant Programme in Jigawa and Zamfara States Report; Save the Children and Action Against Hunger, March 2014 .