Child Survival Week as a platform for promoting vitamin A supplementation in Niger

By Doudou Halidou Maïmouna, Banda Ndiaye and Aissa Diatta

Dr Doudou Halidou Maïmouna is a paediatrician and holds a doctorate in public health. She has more than 20 years of experience in planning, management and monitoring and evaluation of health and nutrition programmes in Niger. Previous positions include National Director of Nutrition/Focal Point for SUN for the Ministry of Public Health in Niger, and Programme Coordinator with Micronutrient Initiative. She is currently international facilitator for the REACH initiative in Burkina Faso and a member of the Epidemiological and Clinical Centre in the Public Health School of Brussels, Belgium.

Banda Ndiaye is the Regional Director for Micronutrient Initiative (MI) Africa. He has almost 30 years of experience in nutrition, public health and international development. Appointed in 2006, he oversees all MI programmes on micronutrient deficiencies in Senegal, Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso and Ghana. In 2013, he obtained the prize ‘Nutrition Champion’ awarded jointly by Transform Nutrition, the research consortium funded by DFID, in partnership with the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) and the SUN Movement.

Dr. Aissa Diatta is a paediatrician with more than 20 years of experience in clinical operations and programme management. She was chief physician of the emergency department at the national hospital in Niamey and is currently responsible for the Division for the prevention of malnutrition in the Department of Nutrition of the Ministry of Public Health.

The authors wish to thank the entire team of the Nutrition Department of the Ministry of Health and all Regional Directors of Public Health Regions who facilitated the implementation of the Child Survival Weeks in Niger. They acknowledge all technical and financial partners, including UNICEF and Helen Keller International (HKI), for their technical and financial support and the good cooperation during the campaigns. Finally, the authors and ENN acknowledge the support of Translators without Borders in translating this article, with special mention of Dona Petkova, Tara Horan, Chris Hall, Pauline Teale and Jeanne Zang.

This article is also available in French from here under ‘online only’ content.

Location: Niger

What we know: In Africa, National Vaccination Days (NVDs) against polio have provided a valuable platform for achieving high coverage of preventive vitamin A supplementation (VAS).

What this article adds: In Niger, NVDs are being replaced with local days that have more limited coverage of target children; integration of VAS into routine health services is not widespread. To address this gap, in 2013, pilot Child Survival Weeks (CSWs) were implemented by the Ministry of Public Health across 17 health districts with the support of UNICEF, the Micronutrient Initiative (MI) and Helen Keller International (HKI). High-impact services, such as deworming and VAS, were provided with high investment in leadership, management-strengthening, logistics, community sensitisation, and monitoring and evaluation. The district VAS coverage (104%) exceeded the national target (80%). More than two-thirds of children received vitamin A in the course of the CSW campaign and at home. The post-campaign reported lower coverage (average 45.2%) but, due to recall bias, is difficult to interpret (it was conducted four months post-campaign rather than one month later). Leadership and management-strengthening activities have been crucial to effective implementation of CSWs in Niger. State funding was low (8%); this has implications for sustainability. The CSW proved a feasible platform for VAS; strengthening routine nutrition activities of health centres and of community activities and addressing obstacles (particularly state funding) are critical to the future of VAS in Niger.

In order to extend child survival from 0 to 59 weeks, Niger’s Ministry for Public Health (MPH) has put in place a range of policies relating to health and nutrition, and a national child survival strategy paper (MPH, Niger [1-3]). This strategy is based on VAS given that it results in a 23% reduction in child mortality (Fawzi, Chalmers, Herrera et al, 1993; Sall, Sylla, Ndiaye et al, 2001). In places where vitamin A deficiency constitutes a public health issue, VAS is recommended for infants and children aged six-59 months as a high-impact intervention to help reduce child morbidity and mortality (strongly recommended by the World Health Organization) (WHO, 2013).

Two vitamin A strategies are currently in existence in Niger. VAS campaigns for children aged six-59 months run since 1999 have consistently been coupled with NVDs held every six months with a coverage rate of over 80%. However, some NVDs have now been replaced with Local Vaccination Days (LVDs), which does not enable effective targeting all children from 0-59 months. Stopping NVDs without putting in place an alternative large-scale system for VAS risks the high coverage rate within the country. With regard to routine, peripheral-level VAS, health workers have not yet integrated vitamin A effectively in their daily activities due to insufficient training or a shortage of capsules. The VAS coverage rate remains very low and varies from region to region (14% in Tillabéri, 82% in Maradi) (MPH [4], 2013).

Given the likely discontinuation of NVDs and enhanced routine supplementation measures, since 2010 Niger has progressively launched pilot CSWs (‘la semaine de survie de l’enfant’ (SSE)) in 17 health districts across the country to offer a range of high-impact services aimed at improved child survival, including VAS. This article sets out to describe how CSWs are implemented in Niger, as well as the results obtained, the difficulties encountered and the main challenges that exist.

Organisation and implementation of CSW

Responsibility for the campaign to eliminate vitamin A deficiency and the provision of vitamin A supplements in Niger is a burden on the MPH’s Nutrition Directorate. In 2013, the department within the Nutrition Directorate responsible for alleviating micronutrient deficiency was nominated as a task force for the coordination of pilot CSWs across 17 health districts with the support of partner organisations. CSWs involve a number of activities organised on a regular basis that offer an integrated package of preventive services directed at improving child survival and maternal health that are recognised for their excellent cost/efficiency (Aguayo, Garnier & Baker, 2007). CSWs are implemented according to the following steps:

Responsibility for the campaign to eliminate vitamin A deficiency and the provision of vitamin A supplements in Niger is a burden on the MPH’s Nutrition Directorate. In 2013, the department within the Nutrition Directorate responsible for alleviating micronutrient deficiency was nominated as a task force for the coordination of pilot CSWs across 17 health districts with the support of partner organisations. CSWs involve a number of activities organised on a regular basis that offer an integrated package of preventive services directed at improving child survival and maternal health that are recognised for their excellent cost/efficiency (Aguayo, Garnier & Baker, 2007). CSWs are implemented according to the following steps:

Step 1: Drafting of a CSW planning guide aimed at health district managers

A number of partner organisations, including MI and HKI, provided the necessary documentation to draw up a planning guide. It was developed based on experiences of implementing training and orientation workshops as part of CSWs across a number of countries, namely Senegal and Ghana (Cisse, et al, 2007; Amoaful, Agble & Nyaku, 2004). The necessary documentation called upon the assistance of other MPH directorates, in particular the maternal and child health directorate, the expanded programme on immunisation, the national malaria control programme and the national helminthiasis control programme. This committee was approved following a decision by the MPH in 2011 and met regularly over a three-month period to put together a draft proposal. This document, entitled Organisation of How to Plan, Implement and Monitor Vitamin A Supplementation as part of CSW, was adopted by a national workshop funded by MI and overseen by a consultant. A number of centralised and decentralised technical service agents and other partner organisations also took part.

The guide is broken down into ten parts which contain all of the necessary banners for successful planning: (1) orientation process, (2) review of previous CSWs, (3)lanning of future CSWs, (4) human resources, logistics and supplies, (5) social mobilisation, (6) training of service providers and administration of vitamin A capsules and de-worming tablets, (7) management, (8) monitoring and assessment, (9) reporting and feedback, (10) financial management/review of CSW action plan and funding. The final version of the guide has been widely distributed among health districts.

Stage 2: Training of instructors and members of the core teams of districts

Three series of three-day training courses were organised in 2012, initially for a pool of 16 instructors (two per region). The directorates/key programmes in charge of children, regional directorates of public health and the Association of Paediatricians were involved. The first in the series took the form of a workshop to select the essential package of preventive health services to be added to the CSW determined by local level needs: deworming; immunisation against measles, tetanus and poliomyelitis; and screening of malnutrition. Additional services are added to this minimum package by districts, such as promotion of exclusive and continued breastfeeding, and treatment of diarrhoea. The second and third series of training have been organised in the regions and districts, respectively.

Stage 3: Choosing the districts and budgeting of the activities of CSWs

In 2013, immunisation days took the form of LVDs and did not cover all of the country’s districts. This information has guided the selection of 17 districts for CWSs. Each chosen district made a budget proposal for the organisation of CSWs (from planning to evaluation by referring to the guide made available to them).

Stage 4: Mobilisation of partners for the Global Alliance for Vitamin A (GAVA) surrounding CSWs

The three technical and financial partners, MI, HKI and UNICEF, set up a consultation framework and established a support plan for CSWs: MI, through UNICEF, funded the purchase of vitamin A capsules, the review of messages for raising awareness during CSW campaigns, a portion of the payments to the teams, and the monitoring and evaluation (M&E) process; HKI financially supported the purchase of accessories, such as reconditioning bags, scissors, the routing of inputs including vitamin A capsules for the regions and/or districts, and the debriefing of health workers and community liaison officers about the administering of vitamin A. UNICEF took care of the remaining team payments, coordination and supervision, vehicle rental and fuel. Strong advocacy from the Nutrition Directorate has mobilised approximately 8% of fuel needs from the Government.

Stage 5: Progress of the CSW campaigns, monitoring and evaluation

Mobile teams comprising health workers and travelled to the villages, door-to-door, to administer the outlined package of activities. Data was monitored daily and the end of the campaign was sanctioned as an outcome of meetings on M&E results. A 30x30 cluster survey regarding VAS and mebendazole coverage during the CSWs in 17 pilot districts was carried out four months after the first visit in March 2013. The survey was conducted by the National Institute of Statistics in collaboration with the Nutrition Directorate.

?Strengthening of the leadership of the and the districts

Leadership and management-strengthening activities have been crucial in the effective implementation of CSWs in Niger. At national level, the Ministry of Health has set up an integration plan for NVDs and SVAs in the survival weeks of the child. An advocacy plan has allowed resource mobilisation in the state’s budget of in 2013, versus 1% in previous years. At decentralised level, the CSW guides have been made available to health districts. At least 90% of the core team’s district members have been trained on this guide. Seventeen out of 42 districts have been included in the pilot phase and have a budgeted micro plan for CSWs. All 17 districts have used CSWs as a platform for VAS, the deworming of children and immunisation against poliomyelitis. The monitoring of activities in the survival weeks of the child is carried out at the end of each half year in the districts. No district has reported a stock-out of vitamin A, relating to at least 80% of their service delivery points. Communication, data collection and reporting tools for training of community health workers have been developed and distributed to the districts. At least 80% of women and childminders have been made aware through communication activities for behaviour change, so that they are able to bring their children to the service delivery points.

Strengthening of the consultation framework for GAVA partners

GAVA partners (MI, HKI and UNICEF) have set up a consultation framework in order to harmonise their interventions, which includes a joint work plan with a clear allocation of the tasks and responsibilities. They have supported the Ministry of Health from planning to evaluation of the results and played an important role in the coordination of activities.

VAS coverage

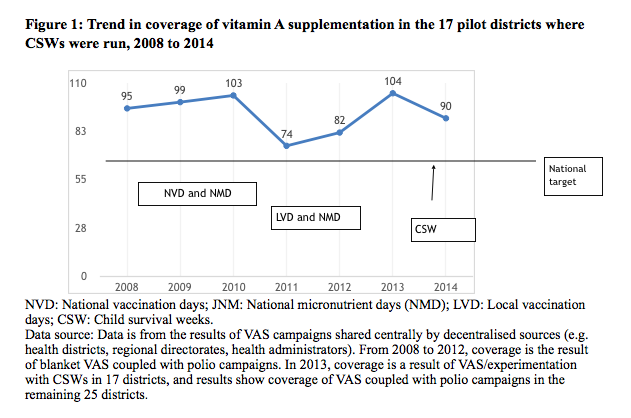

In 2013, the CSWs served as a platform for improving coverage of the main child survival services routinely offered. Distribution of mebendazole was coupled with the administration of vitamin A. Most children in the target group aged six-59 months received VAS in the first (98.5%) and second (103%) visits respectively in 2013 in the 17 pilot districts, including 99.0% and 102% for children aged 12-59 months and 95.6% and 101% for infants aged six-11 months. Thus a high level of coverage of VAS was maintained (Figure 1). The national coverage target set by the country was to achieve a coverage rate of at least 80%. The districts reported that over 80% of mothers or child-minders were informed of the CSW campaign.

In 2013, the CSWs served as a platform for improving coverage of the main child survival services routinely offered. Distribution of mebendazole was coupled with the administration of vitamin A. Most children in the target group aged six-59 months received VAS in the first (98.5%) and second (103%) visits respectively in 2013 in the 17 pilot districts, including 99.0% and 102% for children aged 12-59 months and 95.6% and 101% for infants aged six-11 months. Thus a high level of coverage of VAS was maintained (Figure 1). The national coverage target set by the country was to achieve a coverage rate of at least 80%. The districts reported that over 80% of mothers or child-minders were informed of the CSW campaign.

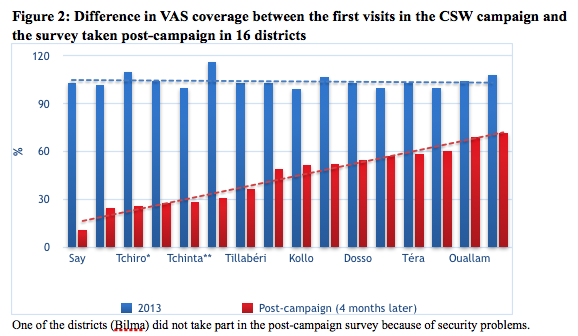

Figure 2 shows the coverage of the campaign in 2013 in 17 districts compared to the the results of a survey conducted four months after the campaign. It is recommended (WHO, HKI) that post-campaign surveys should take place within one month. In Niger, this deadline was not met due to logistical constraints, with the possibility of bias as a result (such as recall bias on the part of mothers). Bearing in mind these limitations, the post-campaign survey results revealed overall coverage of 45.2% of children. Coverage varied by health district, ranging from 10.8% in Say in the Tillabéry region to 71.6% in the Agadez Commune health district. These results also reflect the challenges of achieving good coverage in some areas, despite strong campaign organisation.

Figure 2: This is the cover of the first results of SSE campaign in 2013 in 17 districts compared to the results of a survey that was conducted four months after that first campaign. Normally as recommended (WHO, HKI), post-campaign surveys must take place within one month. In Niger this deadline was not met with the possibility of bias (such as recall bias on the part of mothers). According to the team of the Nutrition Directorate, despite advance planning, logistical constraints did not facilitate the achievement of the post-campaign survey in the period. This was a problem of appreciation on the VAS coverage (low and very low for some districts).

The 80% target is relative to the results of campaigns and VAS that were achieved during the campaigns in Niger. Good covers are those from the countryside.

We wanted the presentation of the results of the post-campaign survey to take into account the difficulties encountered, despite the good organisation of the campaign.

The survey revealed that for mothers or child minders, the main reasons the children had not received VAS was that the teams had not visited the households (36.1%) or villages (31.1%) or the child was absent from the household (11.9%). One fifth (21%) of mothers said they did not know about the campaign. Of the children who received VAS, 97.8% of mothers said the child received their capsule during the CSW campaign and 2.2% during routine activities. Most (90.4%) said the child received their capsule at home and 9.6% at the health centre or public locations (market, water standpipe, etc.).

According to the same survey, 41.2% of respondents were informed of the distribution of VAS during the CSW campaign, whereas, as detailed above, it was reported as over 80% by the districts. This proportion varied from one district to another; e.g. from 16.0% in Arlit to 78.5% in Ouallam. The respondents channels of information were mainly members of the community (town criers, community liaison representatives, family/neighbours and leaders) 75.2%; the media (radio and TV) 50.6%; and health organisations (health officers and mobile teams) 30.6%.

In addition to VAS and deworming with mebendazole, the main additional themes, which were virtually common to all districts, were the promotion of breastfeeding and washing hands with soap and water. Messages about breastfeeding that were enlarged upon by the teams in the CSW campaign and cited by the mothers were: putting the baby to the breast immediately after birth and giving it colostrum (50.2%); not giving anything other than breastmilk for the first six months (32.8%); and breastfeeding the baby frequently, day and night (14.0%)Messages cited about washing hands with soap and water at appropriate moments were: washing hands before preparing to eat (37.5%); washing hands before feeding child (32.2%); washing hands before and after eating (28.4%); and washing hands after using the toilet (25.0%).

Discussion

In Africa, NVDs against polio have acted as a sufficiently financed platform for preventive VAS programmes and have undoubtedly improved visibility for large-scale, regular VAS for children. In light of the gradual abolition of NVDs in most African countries, it is proving necessary to attract decision-makers’ attention to national child survival strategies, including VAS. Some countries have succeeded in establishing CSWs as opportunities to carry out essential child survival activities – including VAS – with a greater reach and in addition to the routine services provided at health facilities (Aguayo et al, 2007). In Ghana, CSWs have offered a package of services, including VAS, vaccination, reimpregnation of mosquito nets, the provision of child health record books and the registering of births (Amoaful et al, 2004).

MPH

On an organisational level, the leadership of the MPH, collaboration between the various departments of the MPH and between the partners, the micro-planning of activities on the decentralised level, and the involvement of the various entities (political, administrative, traditional and religious leaders) in the preparation and implementation of the CSWs has greatly contributed to the success of the SSEs. The principal organisational difficulties related to delays in providing the input materials, reagents, and management tools in some enclaved districts; underestimation of the targets, making it difficult to accurately estimate material needs; the need to increase human resources due to the volume of activities; and the lack of security noted in some locations. A sufficient number of communication media is lacking in several districts.

From a funding point of view, meeting the deadline for the requests formulated by the MPH and making the partners’ funds available in time, and the transparency of the information on rates of indemnities, are noteworthy The delay in setting up funds at the level of some districts for sub-funding some items like social mobilisation was an issue. The state’s contribution was low (8%). Local organisations in some districts in the Tillabéry region made cash contributions or contributed by strengthening the teams’ means of transportation (carts, fuel, etc.). Increasing the state’s budget constitutes a major challenge to carrying out the CSWs. In Ghana, the VAS programme became a national activity; the government takes responsibility for 73% of the costs and the partners take care of the remaining 27% (Amoaful et al, 2007). This made it possible to institutionalise the Child Survival/Health Days.

With regard to evaluation/follow-up, key factors were improvement of management tools, regularity of supervisions, daily validation of the data by team in each district, and holding workshops to evaluate the CSWs with all the stakeholders by district, region, and at the central level. The data were broken down by age and geographic area.

The CSWs have already proven their usefulness, especially in improving national coverages of interventions such as VAS, deworming, and measles vaccination in some countries like Ghana (Amoaful et al, 2007) , Senegal (Begin, Aguayo & Mulder-Sibanda, 2004) and the Congo (Bandenga & Mouyokani, 2007). The VAS coverages obtained at the district level exceeded the threshold of the objective set at the national level (the coverage was 104% in 2013 relative to the national target of 80%). More than two thirds of children received vitamin A in the course of the CSW campaign and at home. This confirms once again the relevance of mass campaigns in VAS in children and the door-to-door strategy used.

According to the literature (Institut National de la Statistique; Thwing, Perry, Ndiaye et al, 2009), in order to assess the equity of the VAS campaigns the survey of beneficiaries is the method most used to evaluate coverage. That survey should be conducted in the month following the campaign in order to catch the children who did not receive the supplement, to detect organisational problems, and to better prepare the next campaign. The survey conducted in Niger was done four months afterwards, which undoubtedly allowed the introduction of bias and made it difficult to interpret the results of VAS coverage. The post-survey campaign helps identify the areas to strengthen before the second round.

The districts that displayed high proportions of mothers informed about the campaign were also those that had relatively better post-campaign VAS coverage. These districts were Téra and Ouallam in the Tillabéry Region; Dosso, Boboye, and Loga in the Dosso Region; and Agadez commune.

For the other interventions (such as breastfeeding promotion and hand-washing), the effectiveness is not strong, but the value added of their incorporation into the CSWs is not negligible with respect to the results of the routine statistical data.

Conclusion

The CSW approach is a multi-disciplinary intervention that was set up in Niger in order to offer Nigerien children a package of free, high-impact services in a door-to-door strategy at the level of districts that were not involved in LVDs. The objectives were achieved with regard to VAS and deworming in children under five. Maintaining the CSWs and the effectiveness and relevance of the interventions will depend on resolving the obstacles encountered; in particular the financial contribution of the state. Nevertheless, given that the CSWs constitute an alternative solution to the abrupt halt of the NVDs, their cessation requires strengthening the routine activities of health centres and of community activities with regard to nutritional monitoring, as well as VAS by community agents.

References

Aguayo V.M., Garnier D., Baker S.K., (2007). Des gouttes qui sauvent: Supplémentation en vitamine A pour la survie de L’Enfant. Progrès et leçons apprises en Afrique de l’Ouest et du Centre [Drops that save: Vitamin A supplementation for child survival. Progress and lessons learned in West and Central Africa]. UNICEF West and Central Africa Regional Office.

Amoaful E., Agble R., Nyaku A., (2004). Sustaining the gains of vitamin A supplementation. Innovative ways of integrating vitamin A supplementation into child health services in Ghana. In: Vitamin A and the common agenda for micronutrients. Report of the XXII International Vitamin A Consultative Group (IVACG) Meeting in Lima.

Bandenga O., Mouyokani I., (2007). Impact of coupling vitamin A supplementation with deworming into immunization activities in the Republic of Congo. In: Consequences and control of micronutrient deficiencies: Science, policy and programs – Defining the issues. Program abstracts. Micronutrient Forum Meeting, Istanbul.

Begin F., Aguayo V.M., Mulder-Sibanda M., (2004). Acceleration of vitamin A supplementation in Senegal. Country assessment report, UNICEF and Micronutrient Initiative.

Cisse D., Diene S.M., Baker S.K., Gaye Y., Bendech M.A., Haselow N.J., (2007). Ensuring twice-yearly vitamin A supplementation in Senegal: assessment validates high coverage. In: Consequences and control of micronutrient deficiencies: Science, policy and programs – Defining the issues. Program abstracts. Micronutrient Forum Meeting, Istanbul.

Fawzi W.W., Chalmers T.C., Herrera M.G., Mosteller F., (1993). Vitamin A supplementation and child mortality. A meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association, (17) 269: 898-903.

Institut National de la Statistique – Ministère de l’Economie, de la Planification et de l’Aménagement du Territoire Enquête post-campagne de vaccination contre la rougeole, d’évaluation de la distribution de la vitamine A et du mebendazole au Cameroun, et d’évaluation des LVD contre la polio dans les régions septentrionales en 2012, [National Institute of Statistics – Ministry of the Economy, Planning, and Land Use. Measles vaccination post-campaign survey, evaluation of the distribution of vitamin A and mebendazole in Cameroon, and evaluation of the national polio vaccination days in the northern regions in 2012] Phase 1. CMR-INS-EPC1-2012.

Ministry of Public Health of Niger [1]. Plan de development sanitaire 2011-2015 [2011-2015 Health Development Plan] (PDS). Retrieved November 2014 from www.who.int

Ministry of Public Health of Niger [2]. Politique Nationale de Nutrition [National Policy on Nutrition].

Ministry of Public Health of Niger [3]. Document de stratégie nationale de survie de l’enfant octobre 2008 [National strategy of child survival document October 2008]. Retrieved November 2014 from www.africanchildforum.org

Ministry of Public Health of Niger [4]. Annuaire statistique de la santé 2013 [2013 Statistical Health Yearbook]. Retrieved November 2014 from www.snis.cermes.net

Sall, M.G., Sylla, A., Ndiaye, O., Diouf, S. and Kuakuvi, N. (2001). Impact de la supplémentation en vitamine A sur la mortalité dans un service de pédiatrie générale au Sénégal [Impact of vitamin A supplementation on mortality in a general pediatric department in Senegal]. Journal de Pédiatrie et de Puériculture, Volume 14, Issue 5, Pages 266-270

Thwing, J., Perry, R. Ndiaye, S. Diouf, M.B., (2009). Evaluation de la campagne intégrée de distribution de moustiquaires imprégnées à longue durée d’action, de vitamine A, et de mébendazole au Sénégal 2009 [Evaluation of the integrated campaign of distributing screens with long-lasting action impregnation, vitamin A, and mebendazole in Senegal 2009]

Retrieved October 2014 from this link.

World Health Organization Supplementation en vitamine A [Vitamin A supplementation]. Retrieved January 2013 from www.who.int