Impact of community-based advocacy in Kenya

By Geoffrey Kipkosgei Tanui, Thatcher Ng’ong’a and Daniel Muhinja

Geofrey Kipkosgei Tanui is currently working as a Community Development Officer for the Kenya Signature Programme with Save the Children International. During the implementation of this project, he was a Public Health Officer with World Vision, based in Turkana County.

Thatcher Ng’ong’a is currently a Senior Programme Officer in the Programme Development and Grants Acquisition Unit, based at World Vision’s office in Nairobi. She was previously the Nutrition Project Manager in Turkana County. Thatcher has five years’ experience implementing nutrition in emergency projects in the arid and semi-arid areas (ASAL) of Kenya, with a brief stint in Kakuma Refugee Camp. She is currently focusing on resource development and development partners’ engagement.

Daniel Muhinja is currently working for World Vision Kenya as a National Nutrition Specialist in the Operations Department. He has over ten years’ experience in nutrition, having worked for the Government of Kenya for three years and for World Vision for seven years in the design, management and monitoring of nutrition programmes.

The authors acknowledge the support of DFID, UNICEF, the Ministry of Health, Bonyo Don Elijah (Associate Director – Policy and Advocacy based at World Vision), and the World Vision Nairobi Office, with regard to the programming reflected in this article. Thanks also to Colleen Emary, Senior Emergency Nutrition Advisor, World Vision International for assistance in the development of this article.

Location: Kenya

What we know: Local-level advocacy is a powerful social tool to improve community services by influencing decision-makers and holding leaders to account.

What this article adds: A World Vision social accountability methodology called Citizen Voice and Action (CVA) empowers citizens to understand and act on their rights. The approach was used in Kenya, where it resulted in substantial local government increases in health resource allocation (committed budget, healthcare worker recruitment, improved services) in rural communities in Turkana and Baringo Counties. In addition, the community’s new-found awareness of their rights to quality health care led to increased utilisation of outpatient services, surpassing immunisation targets and increased the number of children screened and treated for malnutrition. Tools and guidance are available at here.

Introduction

Local-level advocacy is a powerful tool for bringing change in underserved areas in a community. The following article provides two examples where a Citizen Voice and Action approach was used to increase health resource allocation in rural communities in Turkana and Baringo Counties in Kenya.

Local-level advocacy is a powerful tool for bringing change in underserved areas in a community. The following article provides two examples where a Citizen Voice and Action approach was used to increase health resource allocation in rural communities in Turkana and Baringo Counties in Kenya.

As part of health system strengthening, World Vision Kenya in collaboration with the Ministry of Health (MoH) implements a package of nutrition-specific interventions locally dubbed ‘High Impact Nutrition Interventions’. This package includes treatment of acute malnutrition; promotion of good maternal infant and young child nutrition (such as exclusive breastfeeding for six months); handwashing; provision of micronutrients for young children and their mothers through micronutrient supplementation and fortified foods. While the advocacy activities described in this article focused on broader health outcomes, improvements in the utilisation of services for acute malnutrition were observed.

CVA is World Vision’s primary approach to community-level advocacy (CVA, 2014). It is a social accountability methodology which aims to improve the dialogue between communities and government in order to improve services (like health care and education) that affect the daily lives of children and their families. Social accountability refers to civic engagement by communities (other than voting) designed to improve the performance of government. CVA works by educating citizens about their rights and equipping them with a structured set of tools designed to empower them to protect and enforce those rights. First, communities learn about basic human rights and how these rights are articulated under local law. Communities also have the opportunity to rate government’s performance against subjective criteria that they themselves generate. Finally, communities work with other stakeholders to influence decision-makers to improve services, using a simple set of advocacy tools.

Local-level advocacy kicked off in earnest in 2013 in Turkana County against a backdrop of worrying quality of community health services and low levels of health sector staffing and financing. In FY 2013/14, the County Government did not allocate any funds to the public health and environmental health department. The staffing gap for skilled health workers in Turkana Central, South and East sub-Counties stood at 98. World Vision introduced community-level advocacy through the CVA approach with the aim of creating accountability platforms on health service delivery. The CVA approach transformed health service providers to become increasingly responsive and accountable to the communities they serve.

World Vision, in collaboration with MoH officials, mobilised communities to elect community representatives as members of the local-level advocacy and accountability forums. World Vision also sensitised MoH officials on the CVA approach. The goal was to facilitate a common approach in addressing the accountability issues affecting the delivery of community health services in Turkana, Central and East sub-Counties, which serve a population of 530,204 (DHIS).

The process

Phase One: Training

The first phase focused on enabling citizen engagement. World Vision Kenya began by equipping community members with skills to engage in governance issues, which would provide the foundation for subsequent CVA monitoring and advocacy phases. This stage involved a series of processes that raised awareness on the meaning of citizenship, accountability, good governance and human rights (including women’s rights, children’s rights and the rights of people with disabilities). Most importantly, community members learned about how abstract human rights translate into concrete commitments by the Government of Kenya under national law. For example, the Right to Health (Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights) is also included as the ‘right to healthcare services, including reproductive health care’ in Kenya (Constitution of Kenya, 2010), which also includes a child’s right to receive vaccinations at the local clinic health facility.

The first phase focused on enabling citizen engagement. World Vision Kenya began by equipping community members with skills to engage in governance issues, which would provide the foundation for subsequent CVA monitoring and advocacy phases. This stage involved a series of processes that raised awareness on the meaning of citizenship, accountability, good governance and human rights (including women’s rights, children’s rights and the rights of people with disabilities). Most importantly, community members learned about how abstract human rights translate into concrete commitments by the Government of Kenya under national law. For example, the Right to Health (Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights) is also included as the ‘right to healthcare services, including reproductive health care’ in Kenya (Constitution of Kenya, 2010), which also includes a child’s right to receive vaccinations at the local clinic health facility.

The training enhanced communities’ readiness to engage governments in a constructive, productive and well-informed manner. World Vision Kenya rolled out local-level advocacy in Turkana County by providing materials to train nine World Vision nutrition staff and three partners’ staff (two from the International Rescue Committee and one from MoH) in March 2013. In collaboration with the MoH, World Vision identified three community groups (Kawalase, Katilu and Lokori ) from three sub-counties (Turkana Central, South and East). World Vison then trained 36 CVA members (20 males and 15 females) on governance, accountability (their right to quality health services and community social audit process), various policies and standards governing health service provision, the monitoring processes for health service delivery, and engagement with health service providers. World Vision facilitated three chiefs (two males and one female) and three male community health services focal-point persons to provide community sensitisation on local-level advocacy and the selection of community members to form CVA starter groups.

Phase Two: Engagement via community gathering

Community gathering describes a series of linked participatory processes that focus on assessing the quality of public services, such as health care, and identifying ways to improve their delivery. Community members who use the service (especially marginalised groups), service providers (such as health facility staff) and local government officials are all invited to participate. The process, which is collaborative and non-confrontational, hinges on the premise that nobody wants an underperforming service provider in their community, and local authorities are often eager to work with citizens to improve these essential facilities. World Vision Kenya followed four broad strategies in strengthening the collaboration for improving the wellbeing of children. As part of the community gathering, the following sessions were held:

- The initial meeting: At this meeting, citizens, MoH staff and representatives (service providers) and local government representatives (the Chief) learned about the CVA process, its objectives and what they could expect moving forward.

- The monitoring standards meeting: At this meeting, stakeholders recalled what they learned during the enabling citizen engagement phase of CVA; their entitlements under national law; and the service charter, including information such as the services available at the health facility, average waiting time, and cost. In May 2013 World Vision supported 35 CVA members, three community health focal persons and five chiefs (three male, two female) to hold community accountability dialogue meetings. Armed with information from the monitoring standards meeting, the CVA groups visited the health facility and compared the reality on the ground with the stated government commitments. The CVA group used a simple quantitative method to record what they observed. This visit, also known as ‘social audit’, was conducted in Lodwar County Referral Hospital, Katilu Health Center, Lokwii Health Centre, and Lopur and Namukuse Dispensaries.

- The community scorecard process: The scorecard process provided both service users and providers with a simple qualitative method for assessing the performance of service delivery. The scorecard process required service users and providers to compare the health facilities they visited with what an ideal health facility should look like. The CVA groups developed areas of concern in staffing and budgetary allocation at the county level for community health services and environmental hygiene and sanitation. The communities then developed proposals for improving service delivery.

- The interface meeting: At the interface meeting stakeholders shared information from the monitoring standards and scorecard processes with a broader group. In June 2014, in collaboration with World Vision Kenya and health workers from the previously mentioned health facilities, the five CVA groups invited the area chiefs and ward administrators to convene community meetings in Turkana South, East and Central sub-Counties, where they shared the social audit findings. The results, with community input, were then submitted to the county chief officer for health. Based on this information, the community, government and service providers created an action plan to improve the services monitored.

As a result of these four processes, the communities have a wealth of information about what the government has promised to do and what exists in reality. Communities also build essential relationships that strengthen civil society and begin to form actionable plans that will allow them to change the condition of the services on which they depend on a daily basis.

Phase Three: Improving services and influencing policy – submission of the memorandum on increased allocation of budget in public health sector

World Vision, in collaboration with the CVA of health public officials and Kawalase CVA group in Turkana Central, closely monitored the Turkana County FY 2014/15 budgeting process. Focus was drawn to the key areas of concern, particularly community health and environmental health services. World Vision facilitated the chairperson of Kawalase CVA group to collect signatures from community members petitioning the budget committee to allocate Ksh. 20 million ($200,000 USD) and Ksh. 30 million ($300,000 USD) for community health services and environmental health services respectively. The communities, through the CVA group, began the monitoring process again for the FY 2015/16 fiscal period.

The outcome

One of the notable successes of the local-level advocacy in Turkana County was its contribution to healthcare worker recruitment and the County Government’s budgetary allocation to community health services and environmental health services. A memorandum on the budget gap in the public health sector was presented to the Turkana County Assembly Budget and Appropriation Committee during a public meeting organised by Turkana County Assembly on 26 June 2014. The committee considered the submitted memorandum and allocated Ksh. 10 million ($100,000 USD) to the community health strategy and Ksh.5.5 million ($55,000 USD) to environmental health services in the FY 2014/15 budget. This marked the first time in Turkana County that local advocacy groups had influenced budget allocation for the public health sector. In September and October 2014 an additional 309 health workers were recruited (Lutta, 2014) in the five health facilities in which the CVA members conducted a social audit and submitted memoranda on health staffing. The CVA process influenced the recruitment and posting of skilled health workers to these health facilities.

Local level advocacy successes in Baringo county

In January 2015 World Vision Kenya partnered with the MoH and the community to roll out the Illng’arua Health and water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) emergency response project in Marigat sub-County. The project aimed to contribute to improved access to health services among children below the age of five and pregnant and lactating women in Illng’arua by June 2015. The project also aimed to contribute to increased access to safe water for domestic use among the Illng’arua community during this period. The CVA approach, facilitated by World Vision, was employed to engage the Illng’arua community, service providers and local leaders. The Illng’arua community health unit (comprised of 25 community health workers, Marigat sub-county Health Management Team, area chief, ward administrator, county assembly member and 35 village elders) participated in community-level advocacy and accountability dialogues where basic human rights and health care standards were discussed.

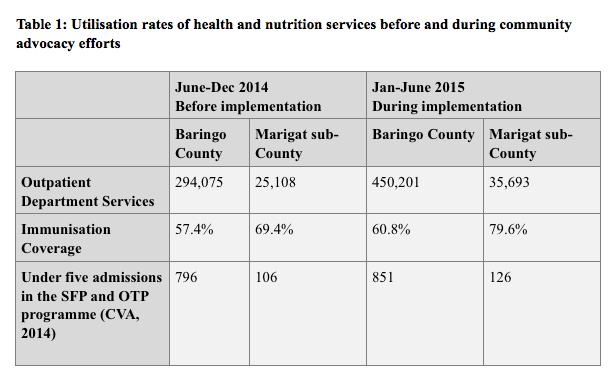

A notable achievement of local-level advocacy in Illng’arua community is the transformation of one of the temporary outreach sites into a dispensary. The County Government of Baringo funded a community proposal worth Ksh. 1.5 million towards construction of Longewan Dispensary. In addition, in an attempt to sustain gains realised by the emergency intervention, partners were successfully mobilised to maintain outreach services beyond the formal closure of the project. The Marigat sub-County Health Management Team continued to provide outreach services in Loropi, while Longewan outreach was provided by Catholic Mission while the construction of the dispensary progressed. In addition, the community’s awareness of its rights to quality health care could have contributed to increased utilisation of outpatient services, surpassing immunisation targets and increasing the number of children screened and treated for malnutrition (see Table 1). Although coverage data for Marigat sub-County are not available, outpatient therapeutic programme (OTP) coverage for East Pokot sub-County (in the same County) is about 46%. It is important to consider that seasonal factors may also have played a role in increased OTP and supplementary feeding programme (SFP) admissions.

Lessons learned

Local-level advocacy is a low-cost yet powerful approach for advocating for resource allocation, impact creation, ownership and sustainability of emergency projects as well as development projects. In Turkana County, a modest investment of about $10,000 USD in CVA training and support for monitoring directly contributed to substantial and long-term investment in the public health sector. By sensitising and training communities on their rights, community-based advocacy is a powerful platform to advocate for resource allocation and accountability.

Local-level advocacy is a low-cost yet powerful approach for advocating for resource allocation, impact creation, ownership and sustainability of emergency projects as well as development projects. In Turkana County, a modest investment of about $10,000 USD in CVA training and support for monitoring directly contributed to substantial and long-term investment in the public health sector. By sensitising and training communities on their rights, community-based advocacy is a powerful platform to advocate for resource allocation and accountability.

Challenges faced in the process included low literacy levels among the community members during the training process, which necessitated use of interpreters. In addition, community members often tended to avoid situations where they are expected to monitor and audit public projects for the purpose of making their leaders account for public money and resources. However, with continuous mentoring, experience and exposure, the CVA groups gained the courage to engage their leaders and demand services.

A recommendation emerging from this advocacy experience is to involve both the private sector and academia from the beginning. Private sector representatives (e.g. businessmen) and academia (e.g. Mount Kenya University) were only engaged in the feedback session to discuss the final report. The advocacy efforts may have a longer-term impact if these two groups had been involved in phase one.

The CVA approach can and has been used by World Vision to influence change in other sectors that are known to contribute to good nutrition; e.g. advocacy directed to government stakeholders in education and agriculture has improved resource allocation to these sectors. Furthermore, establishment of citizen voice action groups leads to empowerment of women and increased opportunities for their economic empowerment, as well as increased education for girls.

Conclusion

The CVA approach is an effective approach for local-level advocacy. In the case of Turkana County, support for local advocacy resulted in substantial investments by local government in sub-County health services through direct increases to the annual budget allocation. While the focus of the advocacy efforts was on improving staffing for the health sector and budget allocations for community health and environmental health, this leads to improvements in malnutrition treatment service resourcing and uptake. CVA also equipped local leaders to continue to monitor health services delivery, thereby strengthening the local accountability mechanisms. In Baringo County, the impact of CVA as a nutrition-sensitive approach was demonstrated by increased utilisation of outpatient services and surpassed immunisation targets, and may have been a contributory factor in the increased number of children screened and treated for malnutrition.

World Vision has developed specific tools for the CVA approach, including a field guide, a video and case studies. These are available here.

For more information, contact: Thatcher Awino Ng’ong’a or telephone: +254 724 668 836.

References

CVA, 2014. Project Model. World Vision International, 2014. www.wvi.org/local-advocacy

DHIS: Kenya District Health Information System 2 (DHIS2). Projected population for 2015 based on census of 2009 population.

Lutta, S,. 2014. Turkana hires 300 health workers to address shortage. Business Daily 20 November 2014.