Developing guidance and capacities for nutrition-sensitive agriculture and food systems: lessons learnt, challenges and opportunities

By Charlotte Dufour

Charlotte Dufour has worked as Food Security, Nutrition and Livelihoods Officer in the UN FAO’s Nutrition Division in Rome since 2010, focusing on sub-Saharan Africa. Her current work includes support to mainstreaming nutrition in agriculture policies and programmes and incorporating food and agriculture in multi-sectoral approaches to nutrition.

Location: Global

What we know: There has been recent unprecedented interest and growing support for enhancing agriculture and food systems’ contribution to nutrition.

What this article adds: A series of guidance and tools have been collectively developed and compiled by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO); these have been informed by regional and country lessons learned, to strengthen nutrition within agricultural structures and complementing broader capacity development efforts. Key principles in this process have been demystifying nutrition, using experience-based evidence, consultation and experience sharing, being practical and meeting the target audience’s programming needs. Such resource development is part of a continuous learning process. Making food and agriculture nutrition-sensitive requires significant shifts in perspective and approaches. The political environment has never been more favourable.

A growing momentum for nutrition-sensitive agriculture and food systems

In the last two years, the international development community has seen an unprecedented interest and growing support for enhancing agriculture and food systems’ contribution to nutrition. The Rome Declaration on Nutrition and its Framework of Action, adopted by 170 countries during the Second International Conference on Nutrition held by FAO and WHO in November 2014, placed a strong emphasis on the role of food systems. In countries that have made nutrition a development priority, in particular members of the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement, partners in the agriculture sector are strengthening their engagement in multi-sectoral nutrition efforts. Major development partners have made nutrition a priority of their agriculture and rural development portfolio (EU/FAO/WB/CTA, 2014; IFAD, 2014; USAID, 2014; DfID, 2015). The global governance mechanisms for agriculture are also repositioning nutrition as central to the evolution of agriculture and food systems: nutrition is being mainstreamed across the work of the FAO, and nutrition challenges and solutions are discussed in the Committee for World Food Security (CFS), as well as the Committees for Agriculture (COAg), Fisheries (COFI), and Forestry (COFO). This political momentum is both carried by, and giving rise to, a growing body of work on crop production and nutrition, livestock and nutrition, nutrition-sensitive value chains, biodiversity and nutrition, natural resources and nutrition and integrating nutrition in agriculture extension.

Note on terminology

In this article, ‘agriculture’ encompasses all food production activities, including crop production, horticulture, livestock, fisheries, and forestry. Programmes commonly called ‘agriculture investment’ programmes are seldom limited to food production and often include value chain development, social development, and rural development. ‘Food systems’ encompass all processes whereby food is produced, processed, transported, marketed and consumed. Finally, the term ‘food and agriculture’ is used to cover both food systems and agriculture.

It is hard to believe that less than five years ago, if one discussed nutrition with an agriculture professional, the reaction would be either: “Nutrition? That’s the business of health, isn’t it?”. Or: “Of course we improve nutrition. We raise income and staple food production.” Meanwhile, many nutritionists with a public health background would remain sceptical of agriculture’s contribution, referring to the limited availability of impact evaluations. To the question: “What are the top ten interventions agriculture can implement to improve nutrition?”, many remained unconvinced by the answer: “It depends on the context. Are you working in a pastoralist setting? With fishermen? In a peri-urban slum?”.

This article describes some of the guidance materials that have been developed to accompany the transition towards a greater understanding of nutrition within the agriculture sector and a greater understanding of agriculture among public health nutritionists. The article focuses on FAO’s experience, but the authors fully acknowledge that what has made progress possible is the collective engagement and efforts of all major development partners. The article highlights lessons learnt regarding the development of these tools that can be of value for other sectors.

These tools are not intended to be stand-alone products that can strengthen capacities in and of themselves. They are meant to complement broader capacity development efforts, in particular country-level technical assistance delivered through on-the-job mentoring, training, and organisational strengthening. Furthermore, they have been produced by building on lessons learnt from country and regional level capacity development efforts, and designed to help scale up similar capacity development initiatives. Indeed, while there has been much progress in terms of building ownership and commitment to strengthen agriculture and food system’s contribution to nutrition, most of the work still lies ahead. And it is urgent to scale up efforts of sensitisation, training and innovation to ensure food and agriculture policies and programmes can help eradicate malnutrition in all its forms.

Existing and upcoming resources for nutrition-sensitive agriculture and food systems

The present section describes a selection of materials developed by the FAO Nutrition Policy and Programme team to guide the design of nutrition-sensitive agriculture policies and programmes, as well as interventions related to social protection and resilience, and multi-sectoral programming for nutrition. This list is not exhaustive. FAO’s Nutrition Division produces a broader range of resources on nutrition education; dietary assessments, for example (www.fao.org/nutrition/en/). And many other organisations have developed useful resources for nutrition-sensitive planning. The Secure Nutrition Platform resources pages (www.securenutritionplatform.org/Pages/Home.aspx) and USAID SPRING Library (www.spring-nutrition.org/library) provide access to many of these tools and resources.

The present section describes a selection of materials developed by the FAO Nutrition Policy and Programme team to guide the design of nutrition-sensitive agriculture policies and programmes, as well as interventions related to social protection and resilience, and multi-sectoral programming for nutrition. This list is not exhaustive. FAO’s Nutrition Division produces a broader range of resources on nutrition education; dietary assessments, for example (www.fao.org/nutrition/en/). And many other organisations have developed useful resources for nutrition-sensitive planning. The Secure Nutrition Platform resources pages (www.securenutritionplatform.org/Pages/Home.aspx) and USAID SPRING Library (www.spring-nutrition.org/library) provide access to many of these tools and resources.

The following set of tools has been developed to guide the design of nutrition-sensitive agriculture policies and programmes:

- Key Recommendations for Improving Nutrition through Agriculture and Food Systems (www.fao.org/3/a-i4922e.pdf) This document is composed of two sets of recommendations. The first ten describe what are key features, or guiding principles, for designing agriculture programmes in a nutrition-sensitive way. It is complemented by a list of five recommendations for optimising the nutritional impact of food and agriculture policies.

- Designing nutrition-sensitive agriculture investments: Guidance and checklist for programme formulation (www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/6cd87835-ab0c-46d7-97ba-394d620e9f38/) This guide is designed to assist programme planners to operationalise the Key Recommendations for Improving Nutrition in Agriculture and Food Systems, through the design of nutrition-sensitive agriculture investments. The guide is composed of a series of key questions, tips and sources of information, which can be used for situation analysis, programme design and programme review.

- The Compendium of Indicators for Nutrition-Sensitive Agriculture (to be published early 2016) This document describes a range of indicators, which can be used to monitor and evaluate the nutrition-related impacts of investments in agriculture and rural development. It is structured around major impact pathways that link agriculture investments to nutrition outcomes including: on farm food production and availability; food environment in markets; income; women’s empowerment; and natural resource management practices. It provides guidance on what each indicator measures and key features of data collection, as well as references to relevant manuals.

- The Compendium of Food and Agriculture Actions for Nutrition (to be published early 2016) This compendium provides a list of interventions related to crop production, horticulture, livestock, fisheries, food processing, forestry and nutrition promotion, which can contribute to improving nutrition as part of a multi-sectoral nutrition strategy. It also includes advice as to how policies and programmes in each of these fields can be better linked to other sectors relevant to nutrition. (Note: the Compendium is an adaptation of the Food, Agriculture and Diets section of the REACH Compendium of Actions for Nutrition. Both publications will be released in 2016.)

FAO is now engaged in developing a set of e-learning modules on nutrition and food systems, which will capture the content of the guidelines described above, in an interactive way using a scenario-based approach and experiential learning. These are being developed through a consultative process involving multiple organisations from academia, civil society, UN organisations and donors. The first module was released in September 2015 and others will be gradually released over the course of 2016.

FAO has also developed specific guidance oriented towards ensuring investments in resilience-building and social protection are nutrition-sensitive:

- Technical paper on Nutrition and Resilience – Strengthening the links between resilience and nutrition in food and agriculture (www.fao.org/3/a-i3777e.pdf): this paper argues that good nutrition is both an essential “input” for resilience and an outcome of resilience. It highlights key areas of convergence between the two concepts, as well as opportunities to enhance the nutritional impact of resilience-building programming in the context of the food and agriculture sector.

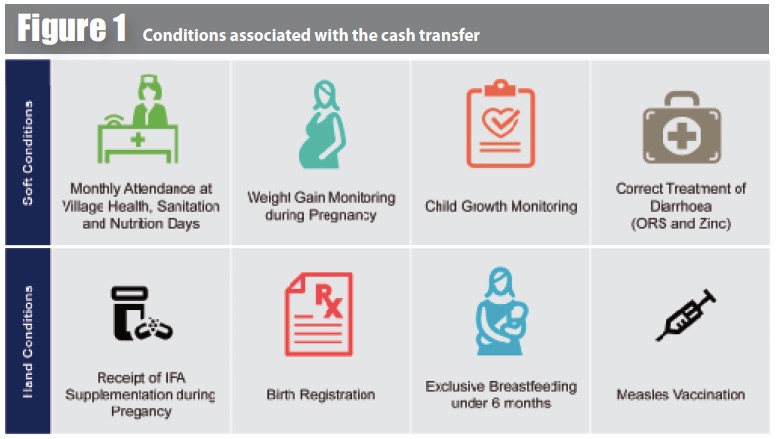

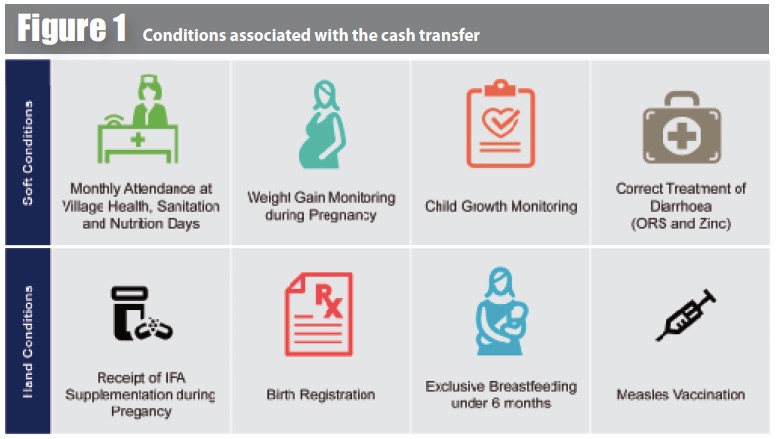

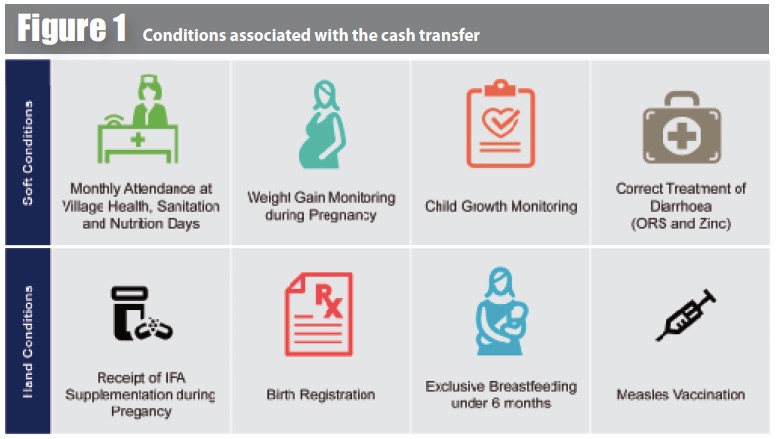

- Technical paper on Nutrition and Social Protection (www.fao.org/3/a-i4819e.pdf): the paper identifies how the main social protection instruments can address the causes of malnutrition, and proposes guiding principles to make these instruments nutrition-sensitive. It also presents each social protection instrument and describes how its impact on nutrition can be enhanced, illustrating propositions with case studies.

Finally, a key feature of making a programme nutrition-sensitive is ensuring it is well embedded in a multi-sectoral approach. FAO has developed the guidelines Agreeing on causes of malnutrition for joint action (www.fao.org/3/a-i3516e.pdf). This document presents a workshop methodology that uses the problem/solution tree approach to inform the design of integrated information systems and programmes, and to develop partnerships for sustainable improvements in nutrition. This tool is very effective to foster a better understanding of the interactions between causes of malnutrition and build consensus among professionals from different sectors on a common strategy.

Principles and approach

The following principles have informed the overall approach for developing guidance and organising capacity development activities for professionals working in food and agriculture:

Demystifying nutrition: One of the obstacles preventing agriculture professionals from addressing nutrition is the anxiety associated with being tasked with doing something beyond one’s competencies, or which increases one’s workload. An important part of developing guidance was thus to emphasise that agronomists would not be asked to distribute vitamin A capsules or measure weights and heights, for example, but rather to apply a ‘nutrition lens’ to the activities they already carry out. It was also important for the message to be conveyed by peers, using the language and approaches common in food and agriculture.

Using ‘experience-based evidence’: When the momentum around agriculture-nutrition linkages started growing around 2010, the scientific evidence base was very limited, especially if one limits ‘evidence’ to randomised control trials, which are usually difficult to apply to research in agriculture and food systems (Pinstrup Anderson, 2013). But the lessons learned emerging from the experience of dozens or hundreds of professionals across institutions tended to point towards similar advice. In 2010, FAO commissioned a review of recently published guidance on agriculture-nutrition linkages and carried out an extensive stakeholder consultation, to assess the level of consensus that existed between organisations on this topic. The rationale was that experience-based evidence should be harnessed to inform policies and programmes concurrent with the gathering of further experimental evidence. The result was the Synthesis of Guiding Principles on Agriculture Programming for Nutrition (www.fao.org/docrep/017/aq194e/aq194e.pdf), which were the foundation for the Key Recommendations for Improving Nutrition through Agriculture and Food Systems (www.fao.org/3/a-i4922e.pdf) (see below). These proved to be a key reference for many institutions and were used to inform advocacy and capacity development activities at global, regional and country level. (Herforth & Dufour, 2014).

Consultation and experience sharing: The business of making agriculture ‘nutrition-sensitive’ is not an exact science, nor are there ‘magic bullets’. It is one which entails identifying entry points and solutions according to local malnutrition problems and livelihoods, the agro-ecological context, and the framework of the programme in which nutrition is integrated. Developing guidance therefore requires the perspectives of professionals from different disciplines and regions, with experience from a diversity of programmes. Much of the guidance has therefore been developed through extensive consultation processes using a variety of forums including the Ag2Nut Community of Practice and the FAO Food Security and Nutrition Forum. Tools have been informed by, and enriched with, the lessons learnt and case studies gathered through knowledge sharing events such as the regional workshops organised by the African Union and New Partnership for African Development for the CAADP Nutrition Capacity Development Initiative (Dufour, Jelensperger, Uccello et al, 2013) and the USAID Agriculture-Nutrition Global Learning and Evidence Exchange (see www.spring-nutrition.org).

Being practical and meeting the target audience’s programming needs: developing guidance for nutrition-sensitive agriculture and food systems requires an understanding of the priorities and planning cycles and processes of the different sectors and sub-sectors involved. For this reason, in FAO, the professionals from the Nutrition Division worked very closely with colleagues from FAO’s Investment Centre, which specialises in the formulation of agriculture investment plans. Guidance for professionals working in livestock, crop production and horticulture, fisheries and forestry, as well as on social protection and resilience, was developed in close collaboration with sub-sector specialists. We also sought inputs from specialists in information systems, monitoring and evaluation, gender and food safety. Many of the tools were first elaborated as guidance for hands-on exercises with field practitioners in the context of training and planning workshops. Practitioners’ feedback on these exercises was then used to inform the design of published materials.

Looking ahead: challenges and opportunities

The experience of developing these guidance materials, and the broader capacity development efforts of which they are part, have shown that it is important to consider such activities as part of a continuous learning process, where materials are regularly enriched with experience. Opportunities for inter-organisation and inter-country experience exchange, dialogue and sharing of experiences are thus essential to ensure relevance and effectiveness. Furthermore, materials are, of course, ineffective if not part of a broad capacity development strategy that simultaneously strengthens individual skills and knowledge, the organisational structures within which individuals work, and the overall policy and programmatic environment within which structures operate (FAO, 2015).

The experience of developing these guidance materials, and the broader capacity development efforts of which they are part, have shown that it is important to consider such activities as part of a continuous learning process, where materials are regularly enriched with experience. Opportunities for inter-organisation and inter-country experience exchange, dialogue and sharing of experiences are thus essential to ensure relevance and effectiveness. Furthermore, materials are, of course, ineffective if not part of a broad capacity development strategy that simultaneously strengthens individual skills and knowledge, the organisational structures within which individuals work, and the overall policy and programmatic environment within which structures operate (FAO, 2015).

Making food and agriculture nutrition-sensitive is on one hand accessible and not ‘rocket science’, but on the other does requires significant shifts in perspective and approaches. For example: adopting a consumer-centred approach as opposed to a food supply-driven approach; nutrition objectives can be at odds with economic objectives of agriculture programmes, or entail opportunity costs. Finally, integrating nutrition in individual programmes may be feasible, but making food and agriculture nutrition-sensitive also requires changes in policies affecting each stage of the food system (input supply, production priorities, regulations around marketing, food standards etc.). Going beyond sensitisation and generating a genuine shift in the way agriculture and food systems operate will thus take time and investments. It will require innovation, multi-stakeholder dialogue, trial and error, improved monitoring and learning, and perseverance.

The political environment has never been more favourable. The growing interest in social protection, which presents big opportunities to leverage agriculture in favour of nutrition outcomes, is an illustration of this. And the centrality of nutrition-sensitive food systems to the ICN2 Framework for Action and the Sustainable Development Goals provide an opportunity to accelerate the strengthening of capacities to make food systems environmentally sustainable and conducive to good health and nutrition.

References

DFID. Department for International Development (UK) (2015). DfID’s Conceptual Framework on Agriculture. www.gov.uk

Dufour, C., Jelensperger, J., Uccello, E., Moalosi, K., Giyose, B., Kauffmann, D., AgBendech, M. (2013). Mainstreaming nutrition in agriculture investment plans in sub-Saharan Africa: lessons learnt from the NEPAD CAADP Nutrition Capacity Development.SCN News 40 (ps 59-66). www.unscn.org

European Commission, UN Food and Agriculture Organization, the Technical Center for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation, World Bank Group (2014). Agriculture and nutrition: a common future. www.fao.org

FAO (2015). Enhancing FAO’s practices for supporting capacity development of member countries.? Learning module 1. www.fao.org

Herforth, A. and Dufour, C. (2013). Key Recommendations for Improving Nutrition through Agriculture: establishing a global consensus. SCN News 40 (p. 33-38)

IFAD. International Fund for Agricultural Development (2014). Improving Nutrition through Agriculture. www.ifad.org

Pinstrup-Andersen, P. (2013). Nutrition-sensitive food systems: from rhetoric to action. Lancet 2013; 382 (9890):375-376.

USAID Feed the Future (2014). Feed the Future Approach (webpage) www.feedthefuture.gov