Integrated food security programming and acute malnutrition prevention in the Central African Republic

By Amanda Lewis, Food Security and Livelihoods Head of Department, ACF Central African Republic

Amanda Lewis is the Head of Department for Food Security and Livelihoods with Action Against Hunger in the Central African Republic. She has experience in food security, agriculture, and nutrition and provides technical support to ACF’s projects in CAR.

This project is financed by the Comité Interministériel d’Aide Alimentaire (Inter-Ministry Committee for Food Aid) of the French Embassy. The author extends thanks to the Project Managers, Ioana Georgescu and Lisa Peyre, and to the field team.

Location: Central African Republic (CAR)

What we know: Since 2013 there has been an ongoing crisis in the Central African Republic (CAR) with associated food insecurity.

What this article adds: During 2015, ACF implemented a short-term (five months with a three-month extension) nutrition security project in Bangui, CAR that integrates food security, nutrition, and mental health and care practices (MHCP), targeting pregnant and lactating women and children 6-24 months of age. It comprises food voucher distribution, creative behaviour change communication, individual and group MHCP sessions, infant and young child feeding (IYCF) sensitisation and support, and one-off cash transfers. To date, women’s individual dietary diversity score and IYCF knowledge, mother-child relationship, and maternal psychosocial functioning have improved considerably. Strong collaboration between food security and MHCP teams included cross-training, joint targeting, harmonised messaging, shared activity delivery and common monitoring and evaluation (M&E) indicators. Challenges related to beneficiary selection, low knowledge base of caregivers and staff, and ongoing insecurity. Further learning will be available post-endline evaluation in early 2016.

Introduction

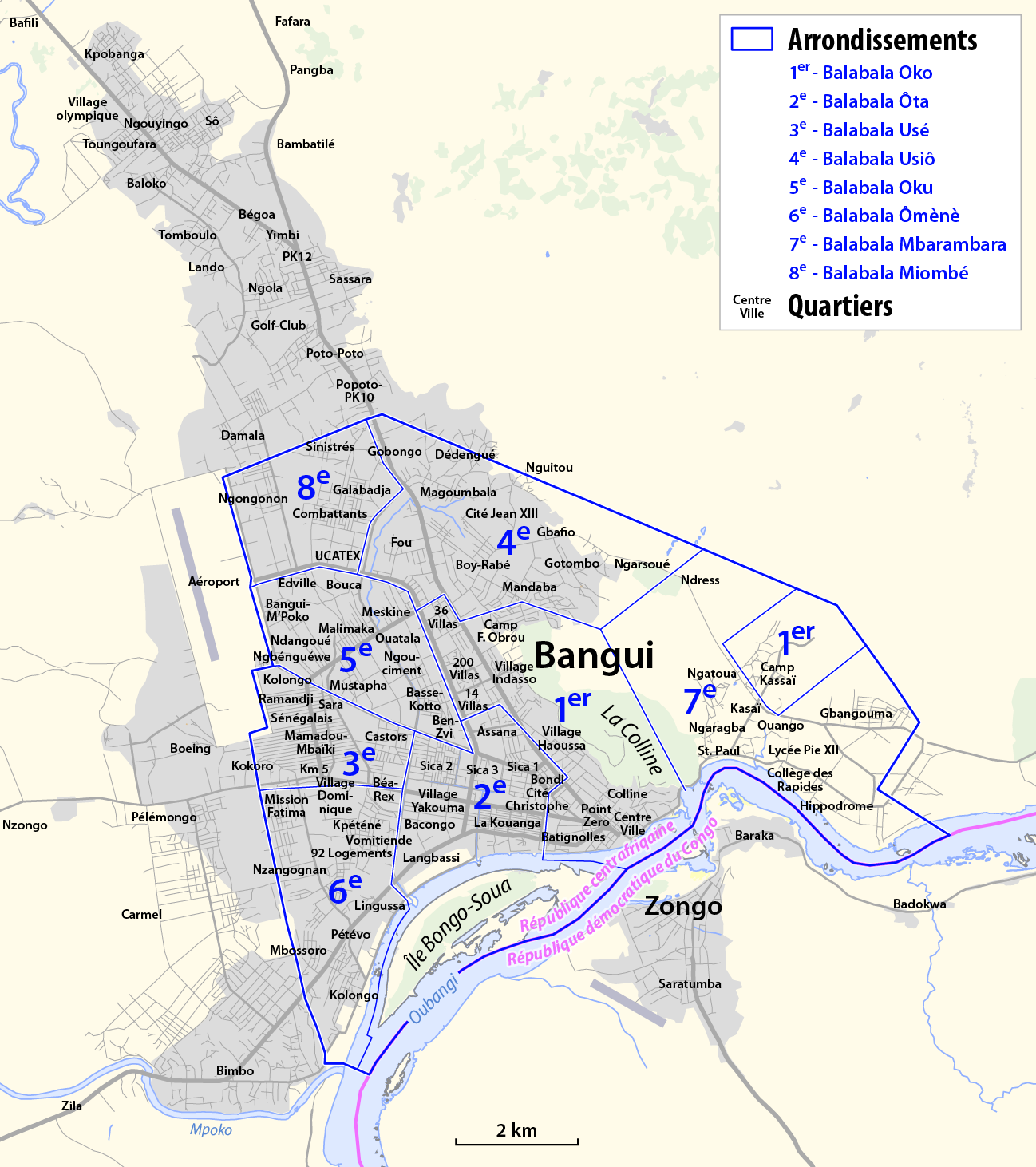

Action Against Hunger (ACF-International) has been present in CAR since 2006, carrying out activities related to nutrition; water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH); food security and livelihoods; and MHCP. The crisis that began in 2013 has greatly affected the population in Bangui (see map), where food insecurity remains high and coping strategies are limited. In this context, ACF is using a nutrition security approach in one of the programmes to address both immediate and underlying causes of malnutrition, integrating food security, nutrition and MHCP. This project is financed by the Comité Interministériel d’Aide Alimentaire (CIAA) of the French Embassy.

Action Against Hunger (ACF-International) has been present in CAR since 2006, carrying out activities related to nutrition; water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH); food security and livelihoods; and MHCP. The crisis that began in 2013 has greatly affected the population in Bangui (see map), where food insecurity remains high and coping strategies are limited. In this context, ACF is using a nutrition security approach in one of the programmes to address both immediate and underlying causes of malnutrition, integrating food security, nutrition and MHCP. This project is financed by the Comité Interministériel d’Aide Alimentaire (CIAA) of the French Embassy.

This project was preceded by three short-term food voucher projects also funded by the CIAA. In the current project, ACF has expanded the nutrition-sensitive elements of the project to have a greater impact on preventing malnutrition and reducing food insecurity. Targeting 900 pregnant and lactating women (PLW) and women with children under two years of age, this five-month project supported access to a diverse diet through the use of food vouchers, including nutrition messaging using a variety of communication methods such as cooking demonstrations and theatre groups, and provided support to improve childcare practices through group interactions and individual support to women in psychological distress.

The project was planned for a period of five months, from May to September 2015, with three months of coupon distributions (June to August). It was extended by three months (originally one month) due to violence leading to suspension of activities during October 2015 of several supplemental activities detailed below. These activities were due to be carried out in November and December 2015 at the time of writing.

Project context

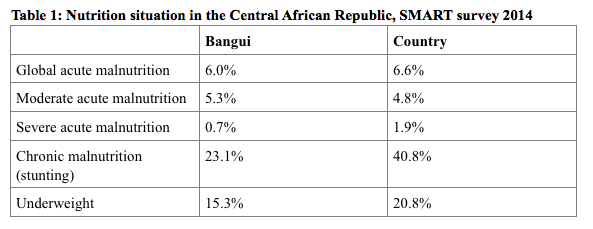

The project was implemented in a context of high levels of food insecurity. The October 2014 Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) analysis classified the food security situation in project areas as ‘crisis’ level. While this has improved to ‘stressed’ according to the April 2015 IPC report, the needs remain great, with 20% of the population in Bangui considered in a humanitarian needs phase. The nutrition situation in CAR is also worrying, with a classification by WHO in the ‘alert’ category. Nutrition statistics from the most recent SMART survey in 2014 are provided in Table 1.

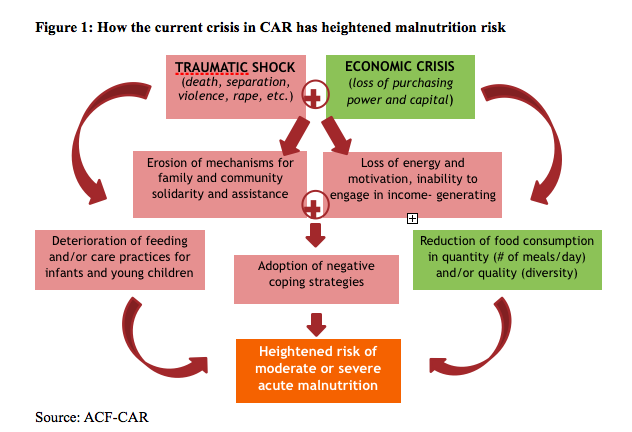

Care practices that promote positive nutrition outcomes for infants and young children are weak. The exclusive breastfeeding rate in Bangui is 20.5%, and only 44% of mothers give at least two meals a day to their infants aged 6-8 months. Mothers feed cereal and clear gruel to young children in small amounts, while animal-source proteins and fruits and vegetables are less frequently given. Although the causes of malnutrition in CAR have not been systematically studied, issues related to food insecurity and care practices play a role, alongside other underlying causes such as limited access to healthcare services, water and sanitation. Figure 1 illustrates the ways in which the current crisis has heightened the risk of malnutrition.

Project approach

Objectives

This ACF project addresses these multi-sectoral issues with the objective of preventing severe and moderate acute malnutrition among 900 PLW and their children under two years of age in Bangui. The project has two specific aims:

- Infants and children aged 6-24 months old and PLW will have improved access to sufficient amounts of high quality food; and

- PLW and mother/infant pairs affected by the crisis will improve their feeding and care practices.

Location

The project is implemented in the 7th arrondissement in Bangui. ACF has worked with the nutrition treatment centre in this area, Centre St. Joseph, since 2009; the previous three food voucher projects also took place in this arrondissement. According to the most recent information available, there are 12,897 households living in the 7th arrondissement, thus this project covers 7% of the general population.

Beneficiaries and targeting

Beneficiaries were selected through a community-based committee that was established with a representative from each quartier (neighbourhood). Using population data, a quota was set for each quartier and the committee selected 900 beneficiaries according to vulnerability criteria. These included being in the last three months of pregnancy or having a child under two and being economically vulnerable, i.e. having no or very limited income source (a list of economic activities was created with the community), and being isolated without a partner or family to provide financial support. The list of project participants was validated by ACF staff by checking a random selection of 10% of households to ensure that the criteria were followed by the committee.

Beneficiaries were selected through a community-based committee that was established with a representative from each quartier (neighbourhood). Using population data, a quota was set for each quartier and the committee selected 900 beneficiaries according to vulnerability criteria. These included being in the last three months of pregnancy or having a child under two and being economically vulnerable, i.e. having no or very limited income source (a list of economic activities was created with the community), and being isolated without a partner or family to provide financial support. The list of project participants was validated by ACF staff by checking a random selection of 10% of households to ensure that the criteria were followed by the committee.

Implementation

Each beneficiary received a monthly distribution of food coupons for three months, exchangeable in the local market. The coupons provided a nutritious food basket consisting of cassava, cowpeas, groundnut, vegetable oil, fish, beef, tomato, rice and salt, and were printed with the monetary amount exchangeable for each food item. This food basket was established with the input of ACF-CAR’s nutrition head of department during a prior coupon project to provide 50% of the food needs for a household of five people (the official household average size). The coupons provide approximately 135,900 kcal per month per household. For a household of five people, this would provide the equivalent of approximately 900 kcal per person per day. The coupons provide a ratio of 11% protein: 56% carbohydrates: 33% fats.

To avoid negatively impacting markets and vendors, the quantity of food exchangeable for the cash amount was not prescribed. However, weekly market price surveillance and beneficiary feedback allowed the team to respond if food vendors increased prices for the participants. The food vendors participating in the project also received training on marketing and business management, as this was identified as a weak point in previous projects.

During the weeks when the voucher distributions were not taking place, the food security team carried out cooking demonstrations with small groups of project participants. This showed how to prepare a balanced porridge for complementary feeding, as well as training on household economics using an interactive game in which participants practiced decision-making and learned about balanced diets and the importance of savings. During the last voucher distribution, a theatre group acted out a comic sketch summing up the different themes covered during the project, including dietary diversity, managing income and savings, and using positive care practices. A radio show with these messages was also broadcast for wider impact.

Alongside the food security team, the MHCP team provided individual and group support to the project participants. Many of the women had suffered loss and abandonment during the crisis and the team saw high rates of depression and anxiety. The individual case management helped mothers to bond with their infants and find strength and support. The group activities provided an environment for mutual learning, exercise of good childcare practices and reinforcement of social ties. The MHCP team also provided sensitisation on care practices, including breastfeeding and IYCF. These sessions were a chance for women to ask questions and discuss issues that were important to them, such as family planning and women’s health. The team also trained 25 healthcare personnel from the St. Joseph’s Health Centre, where the project activities took place, on topics including IYCF, mother-infant attachment and the relationship between patient and caregiver.

The project extension, referred to above, included a cooking demonstration for adults to complement the child-targeted porridge demonstration already completed; the distribution of a ‘baby kit’ containing cloth diapers, soap, and a bathing basin, as well as training on how to use these items; and the distribution of 10,000 CFA (approximately 16 USD) in cash, along with a final theatre group sketch to remind beneficiaries of the project messages. This activity was ongoing at the time of writing, so final evaluation findings related to these activities are not yet included.

Working multi-sectorally

To achieve both aims of the project an integrated approach is required, bringing together access to and use of nutritious food with support for MHCP. While both aims were present in previous projects, in this instance the activities were combined more intentionally, including training and collaboration between food security and MHCP teams. For example, the programme managers provided cross-sector trainings to ensure that food security field staff understood the MHCP messages and that the MHCP teams understood the food security messages. This allowed the food security team to refer beneficiaries to the MCHP team for individual support when they became aware of needs and it strengthened the team approach to the project. The beneficiary targeting and voucher distributions were carried out by both teams. Project activities and messaging were also harmonised; for example, the food security and MHCP teams worked together on the cooking demonstrations, highlighting messages on IYCF care practices, as well as dietary diversity and budgeting for a healthy diet. The two programme managers collaborated to create harmonised M&E questionnaires that addressed the indicators for both sectors. As described above, the ACF-CAR nutrition department was also involved in determining the coupon food basket and validated the key nutrition messages for the trainings and the radio broadcasts.

Project impact

ACF’s Nutrition Security Policy helped inform the mix of nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive activities in this project. The project includes specific nutrition indicators and focuses on the most nutritionally vulnerable population in an area with high levels of food insecurity. It also focuses on empowering women and includes behaviour-change strategies for nutrition and care practices. These nutrition-sensitive characteristics have been shown to have impact in other projects. While it is not possible to separate out the effects of the different components of this project, the project evaluations do point to a number of positive impacts, which are described below.

The women’s average individual dietary diversity score (IDDS) was five at baseline, with a number of women declaring that they had not eaten at all the previous day. At endline, the IDDS average had increased to eight and all women had a score of at least four. Improvements in the food consumption score (FCS) were also noted. At baseline, FCS score was 31, with 33% of households in the poor consumption category. By endline, the average score had risen to 50 and no households fell into the poor category. For infants, at baseline there were two cases of SAM and one case of MAM. By the end of the project, there were no SAM or MAM cases and 65% of infants had improved their MUAC score, with 97% having an adequate MUAC in the endline sample. During the intervention (between baseline and endline), no MAM or SAM cases were detected by the team.

The women’s average individual dietary diversity score (IDDS) was five at baseline, with a number of women declaring that they had not eaten at all the previous day. At endline, the IDDS average had increased to eight and all women had a score of at least four. Improvements in the food consumption score (FCS) were also noted. At baseline, FCS score was 31, with 33% of households in the poor consumption category. By endline, the average score had risen to 50 and no households fell into the poor category. For infants, at baseline there were two cases of SAM and one case of MAM. By the end of the project, there were no SAM or MAM cases and 65% of infants had improved their MUAC score, with 97% having an adequate MUAC in the endline sample. During the intervention (between baseline and endline), no MAM or SAM cases were detected by the team.

Using Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices (KAP) surveys allowed the team to evaluate changes in participants’ perceptions relating to care practices. There was a significant rise in knowledge across all the key messages (exclusive breastfeeding, complementary feeding practices, maternal nutrition, etc.). Due to the short implementation period, feeding practices were not assessed. All the women who received individual MHCP case management had improved their mother-child relationship (ACF, 2013). In addition, 94% of women demonstrated improved psychosocial functioning; ‘suffering scale’ scores improved from an average of 9.24 at admission to 2.8; and the social support score improved from 3.8 to 8.6, using standard suffering and social support scales. (These use a set of drawings to capture participants’ perceptions of social support they receive and their suffering. Decreasing suffering score denotes an improvement; an increasing social support score shows more support received.)

Despite the project’s short duration, these results provide strong evidence for improvements in food security, knowledge related to IYCF and care practices, and feelings of social support among the project participants. The participants’ response was overwhelmingly positive regarding the quality and usefulness of the different project components, including both the access to food and the knowledge gained; 97% stated that they had learned a lot from the project activities.

Project reflection

The project was not without its challenges. These included issues with beneficiary selection, the short duration of the project that limited the depth of individual care that could be provided and limited the ability to measure longer-term behaviour change, and the fact that some beneficiaries (5% according to endline surveys) preferred to sell some of their coupons to have money for non-food needs.

Lessons learned from the challenges with the community-based beneficiary selection have helped us to adapt the selection methodology when designing another food voucher project (with a different donor). In this new project, beneficiary selection committees were developed in each quartier rather than one committee for the whole arrondissement, and the preliminary list of potential beneficiaries created by the committee was validated 100% by ACF teams to ensure that all potential participants met vulnerability criteria. This approach greatly reduced complaints and will be recommended for future coupon projects in Bangui, where the crisis, in addition to the urban setting, contributes to a lack of social cohesion and trust.

Some beneficiaries were selling or exchanging their coupons for cash. Reasons for this included the fact some young women were pressured by household members to provide for non-food needs and had little power to make their own decisions on the matter. In other cases, the women felt that having the cash to invest in their livelihood activities would give greater returns. While ACF staff emphasised the importance of a diverse diet and the use of the coupons to help achieve this, and stressed with the food vendors that exchanging coupons for cash was not allowed, it was not possible to avoid all exchanges for cash. Related to this issue, many women expressed a strong need for assistance not only with access to food, but more importantly for assistance to start or strengthen income-generating activities. Empowering women economically can be a tool for reducing malnutrition, especially when paired with behaviour change communication such as used in this project.

Furthermore, beneficiaries and even health centre staff lack knowledge on IYCF and care practices. Many of the participants did not have basic information on hygiene practices and dietary needs, and very few had knowledge of household money-management. In this context, the project participants were very eager for information and were active participants in the trainings; some even attended the same training several times. In order to make the information accessible within the short timeframe of the project, it was important to keep the activities interactive and participatory. Using games, theatre, hands-on demonstrations and small group activities helped to promote these messages and engage with the women. Other strengths of the project included having team members with experience from the previous coupon projects who were excited to add more depth to the project, and a programme manager who had strong creative, as well as team management, skills.

Further learning will be possible after the final evaluation following the extension activities. It will be especially important to see if food security indicators, perceptions of social support and knowledge of care practices remain positive, or if the situation has deteriorated despite the new distributions following the upsurge in violence in September and October 2015.

Conclusion

This article focuses on ACF’s experiences at a programming level. While lessons learned from the project are being used to impact further programming, as described above, and have been used and shared in coordination with other NGOs working on food voucher programmes in the country through the food security cluster and other NGO coordination mechanisms, scale-up at the level of ministries or state institutions is not currently feasible due to the state of crisis in the country.

This article focuses on ACF’s experiences at a programming level. While lessons learned from the project are being used to impact further programming, as described above, and have been used and shared in coordination with other NGOs working on food voucher programmes in the country through the food security cluster and other NGO coordination mechanisms, scale-up at the level of ministries or state institutions is not currently feasible due to the state of crisis in the country.

Drawing on the ACF nutrition security approach, which stresses synergies and holistic, integrated approaches, this project brought together the food security, nutrition, and MHCP sectors to create a multi-dimensional intervention that addresses a number of the possible causes of malnutrition in Bangui. By improving access to nutritious food and promoting positive care practices and psychosocial support while integrating nutrition messaging into all project activities, the project aimed to improve the food security, nutrition and coping strategies of the project participants. Even with a food voucher distribution project that is focused on responding to the short-term impacts of the current crisis, it is possible to work towards more sustainable, long-term goals of behaviour change and impact through engaging beneficiaries in relevant activities that creatively promote dietary diversity and improved care practices.

While this project took place in an emergency setting, it is possible to imagine a similar approach in other contexts where commodity vouchers are paired with multi-sectoral messaging and support for improved care practices, mental health for mothers, and dietary diversity. In the current context, ACF-CAR hopes to continue this approach, while adding further support to the development of women’s economic activities as described above to promote resilience and economic empowerment that can also have an impact on food and nutrition security.

For more information, contact: Amanda Lewis.

References

ACF, 2013. Using a Mother-Child Interaction observation grid, based on a scoring system (1 = always or constant, and 2 = occasional or absent and 0 = not observed) for listed interactions between the child and his/her mother (refer to ACF, 2013, Manual for the integration of child care practices and mental health into nutrition programmes, Table 6.)