Global Forum on Nutrition-Sensitive Social Protection Programmes

Editorial note: As discussed in the editorial of this issue of Field Exchange, there is a lack of clarity and resulting confusion as to what actually constitutes a nutrition-sensitive intervention. In other words, what are the intrinsic elements and variables that help define whether an intervention is nutrition-sensitive or not? This inevitably leads to subjective classification and lack of harmonisation of definition. It was therefore of interest to the ENN to examine how the authors of the various case studies presented at the Global Forum on Nutrition-Sensitive Social Protection Programmes in Moscow in September and the organisers of the meeting classified nutrition-sensitive programming, i.e. what criteria were utilised.

SecureNutrition and the Russian Federation hosted the Global Forum on Nutrition-Sensitive Social Protection Programmes in Moscow, Russia, from 10 to 11 September 2015. The role of effective nutrition-sensitive social protection programmes has been increasing and the current global development agenda calls for raising the profile of nutrition by ensuring strong leadership and commitment at all levels and across multiple sectors. The Global Forum on Nutrition-Sensitive Social Protection Programmes looked to support these efforts by contributing to the evidence base for policy options and operations/operational actions.

The Global Forum aimed to:

- Better understand existing needs of countries to assist them in setting up well-functioning, nutrition-sensitive social protection programmes;

- Support countries in catalysing, building commitments for, designing, establishing, managing, and scaling up nutrition-sensitive social protection programmes;

- Disseminate best policies and practices and innovative approaches;

- Improve access to knowledge and build awareness related to nutrition-sensitive social protection;

- Facilitate south-south and triangular cooperation and exchange of experience and lessons learned;

- Enhance coordination and cooperation among development partners; and

- Promote engagement of all interested stakeholders.

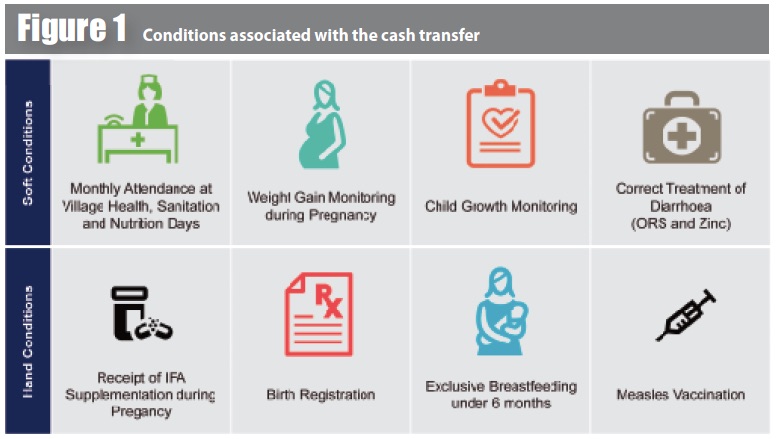

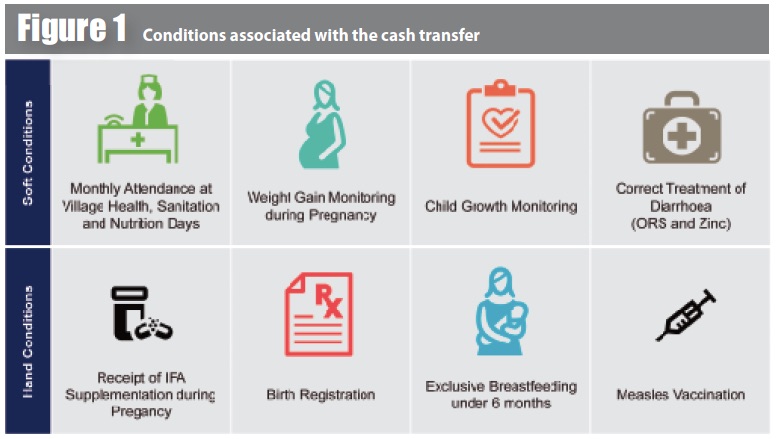

Among the case studies presented at the meeting, 21 have been analysed by the ENN in order to better understand similarities and differences between social protection programming design. Some of the features (but not all), such as behaviour change communication (BCC) and multi-sector approach, relate to nutrition sensitivity. Key nutrition-sensitive characteristics of the country experiences are included below and summarised in Figure 1.

Defining ‘nutrition-sensitive’

Reflecting on the presentations, there appear to be five main aspects that cut across all of the programmes making them nutrition-sensitive. These are:

- The promotion of health and nutrition services;

- The delivery of training/capacity-building/education and good food behaviours;

- Increased resilience to food insecurity;

- A focus on the most nutritionally vulnerable;

- Increased coordination between social protection, health, and nutrition stakeholders.

1. Promotion of health and nutrition services

The programmes in Indonesia, Tanzania, Mexico and the Dominican Republic have a strong focus on the promotion of health and nutrition services.

The Indonesia programme (PNPM Generasi Programme) does this through the delivery of incentivised block grants. The Tanzania programme (Tanzania Productive Social Safety Net) also does this through regular and longer-term support that promotes access to health facilities through compliance with health-related requirements. Similarly, Mexico’s programme (MX Social Protection/PROSPERA Programme) delivers cash transfers to beneficiaries based on specific co-responsibilities relating to health/nutrition service utilisation.

Finally, the Dominican Republic’s programme (Progresando con Solidaridad) has a conditionality that ensures that beneficiaries have to regularly participate in preventative medical care, such as application of vaccination and attendance of primary health care child growth and development check-ups.

2. Delivery of training/capacity-building/education and promotion of good food behaviours

Programmes in Indonesia, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Cabo Verde, Kenya, Republic of Congo, Myanmar, Kyrgyz Republic, Haiti, Syria, Brazil, Nigeria and Mexico all have components related to training/education and promotion of good food behaviours.

Indonesia’s PNPM Generasi Programme provides training and capacity-building for communities to promote long-term education on nutrition and good food behaviours. Ethiopia’s Programme (Productive Safety Net & Households Asset Building Programme) engages in behaviour change communication sessions whereby clients are expected to participate in at least six sessions. Similarly, the Kenyan Programme (targeted at orphans and vulnerable children) has focused promotion sessions of vitamin A supplements, as well as awareness-raising activities at community level. Mexico’s MX Social Protection/PROSPERA Programme also provides nutritional support and cash transfers based on attendance of health/nutrition sessions.

Both Haiti (Appui au Programme National de Sécurité Alimentaire et de Nutrition) and Nigeria (Child development and Grant Programme) also have a focus on education and good food behaviours to attempt to address underlying causes of under-nutrition and ensure children are born healthy and nurtured effectively.

Finally, the Brazil (Zero Hunger Strategy), Kyrgyz Republic (Optimising Primary School Meals Programme) and Cabo Verde programmes (National School Nutrition Programme) all aim to build healthy food habits in children of school age. These programmes all specifically focus on the nutritional needs of school-age children and how best to incorporate this into ‘school feeding’. These programmes also all aim to promote and educate children on healthy eating and good food habits.

3. Increased resilience to food insecurity

The Programmes in the Republic of Congo, Mali, Haiti, Nigeria and Syria all have a particular focus on resilience to food insecurity.

The Republic of Congo Programme (Nutrition-sensitive Urban Safety Net Programme) aims to increase resilience to food insecurity and undernutrition in the long term particularly by providing nutrition assistance and promoting positive behaviours to combat under-nutrition in periods of food insecurity. In Haiti the Bureau of Nutrition and the Ministry of Health (MoH) work together to define the composition of the food basket to ensure it is nutrition-sensitive. In practice, 40% of the value of the monthly USD 25 voucher to procure a locally produced food basket has to include fresh nutritious foods such as vegetables, fruits and meat products, thus providing a long-term social safety net for food insecurity. Nigeria’s programme aims to address the underlying causes of food insecurity. The programme has built in components of infant and young child feeding (IYCF) and nutrition Behaviour Change Communication (BCC) to address some of these underlying causes of undernutrition, such as poverty, food security and health and nutrition practices. Syria’s programme (fresh food vouchers for pregnant and lactating internally displaced women) aims to combat conflict-induced food insecurity by ensuring that the food vouchers given can only be used to purchase, from participating shops, specified fresh foods that complement WFP food baskets. Mali’s programme (Emergency Safety Nets Project), through specific targeting, aims at building resilience among those most at risk of undernutrition.

4. Focus on most nutritionally vulnerable (pregnant/lactating mothers, babies and young children)

The programmes in Indonesia, Bangladesh, Myanmar, the Philippines and Nigeria all have a very specific nutrition focus on pregnant/lactating mothers, babies and young children.

Indonesia’s programme targets most high-risk groups in the poorest households. These include pregnant women and children under two years old. Bangladesh’s Programme (Income Support Programme for the Poorest) has a similar component with a specific gender focus that targets pregnant women and/or women with children below the age of 60 months. This programme particularly focuses on growth-monitoring and child nutrition and development sessions. Similarly, the programmes of Myanmar (Tat Lan Programme: Maternity Cash Transfers) and Nigeria have a strong focus on BCC for optimal IYCF behaviours. Myanmar’s programme also focuses on health-seeking hygiene and maternal care, particularly during the first 1,000 days. The Filipino Programme (Philippines Social Welfare Development and Reform Project) seeks to meet objectives of keeping children healthy and reducing stunting and long-term health complications related to poor nutrition.

5. Increased coordination between social protection, health and nutrition stakeholders

Two of the programmes explicitly coordinate social protection, health and nutrition stakeholders. Both the Djibouti and Indonesia programmes have a strong component related to enhancing sectoral coherence by increasing coordination and linking social protection and nutrition interventions. The Djibouti Programme (Social Safety Net Project) is at the forefront of a longer-term national social protection strategy.

For more information, visit here.