Integrating MIYCN initiatives across sectors in Dadaab refugee camps in Kenya

By Doris Mwendwa, James Njiru and Jacob Korir

Doris Mwendwa is the current National MIYCN Deputy Programme Manager and has been working with ACF-USA Kenya Mission for the past four years, both in MIYCN and IMAM projects.

James Njiru is currently the coordinator for Social Behaviour Change, MIYCN, Research and M&E, Gender and Advocacy in ACF. He has previously worked for the Ministry of Health at national level.

Jacob Korir is current Head of the Nutrition and Health Department in ACF-USA Kenya Mission and has over five years experience in nutrition and health programming. He previously worked for Provide International, World Vision Somalia, Kenya Medical Research Institute and Christian Child Care International in various health and nutrition capacities.

Location: Dadaab refugee camp, Kenya

What we know: In many refugee contexts, maternal undernutrition and sub-optimal IYCF practices contribute to the burden of acute malnutrition.

What this article adds: In 2011, UNHCR and partners renewed efforts to support maternal and IYCF nutrition (MIYCN) in established and new Dadaab refugee camps in Kenya where GAM and maternal anaemia were prevalent and feeding practices sub-optimal. Led by ACF, the initiative developed a common results framework and communication model with nutrition and health services and allied sectors such as WASH and livelihoods. Mother-to-mother support groups were at the cornerstone of the intervention. By 2014, GAM rates had fallen in the camps, largely attributable to improved MIYCN. A pilot of the UNHCR IYCF friendly framework will build on lessons and success to date.

Background

Dadaab refugee complex situated in Garissa County, a semi-arid part of North Eastern Kenya, was established in 1991 to cater for an influx of refugees from Somalia. Dadaab refugee complex has five camps; IFO, Hagadera and Dagahaley (in existence for 20 years) and two newly established camps; Kambioos and IFO 2, set up to host the new arrivals that came as a result of the 2011 influx following the worst famine in the Horn of Africa in 60 years. The total population of registered refugees as of 31 August 2015 is 349,280; this has reduced from 450,000 (2011) due to recent efforts made through the tripartite agreement between the Kenyan and Somali Governments and UNHCR on voluntary repatriation.

Dadaab refugee complex situated in Garissa County, a semi-arid part of North Eastern Kenya, was established in 1991 to cater for an influx of refugees from Somalia. Dadaab refugee complex has five camps; IFO, Hagadera and Dagahaley (in existence for 20 years) and two newly established camps; Kambioos and IFO 2, set up to host the new arrivals that came as a result of the 2011 influx following the worst famine in the Horn of Africa in 60 years. The total population of registered refugees as of 31 August 2015 is 349,280; this has reduced from 450,000 (2011) due to recent efforts made through the tripartite agreement between the Kenyan and Somali Governments and UNHCR on voluntary repatriation.

During the emergency response in 2011, the gains that had been made in improving infant and young child nutrition (IYCN) among children under five years was considerably eroded due to lack of effective monitoring and integration of activities into the mainstream routine health and nutrition programmes. The situation was further exacerbated by the influx of Somali refugees and setting up of new camps. Results from the 2011 annual survey conducted in the refugee camps indicated a global acute malnutrition (GAM) rate of 20.4%, with exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) rates at 47.1% in Hagadera, IFO main 43%, Dagahaley 68.1% and IFO 2 41.2%. These were worse overall compared to previous years.

In order to scale up MIYCN activities urgently, UNHCR and UNICEF approached Action Against Hunger (ACF) with a primary goal of revitalising dormant MIYCN structures in the older camps, establishing structures in the new camps (Kambioos and IFO 2) and strengthening the existing structures in Hagadera. These activities were aimed at strengthening, integrating and sustaining MIYCN interventions within the mainstream health and nutrition programmes of partner organisations (International Rescue Committee (IRC) in Hagadera and Kambioos camps; Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF Swiss) in Dagahaley camp; Islamic Relief Kenya (IRK) in Ifo main camp and Kenya Red Cross Society (KRCS) in Ifo II camp), as well as building their capacity.

Approach for establishing and revitalising MIYCN structures for improved nutrition outcomes

Various strategic engagements and discussions were held between ACF, UNHCR and implementing partners to aid in the integration of MIYCN into routine health and nutrition activities for improved health and nutrition outcomes. Capacity-building on MIYCN was conducted with partners to equip them with the necessary skills to protect, support and promote appropriate feeding practices. There was advocacy to partners on allocation of funds for preventive activities such as immunisation, micronutrient supplementation and MIYCN, especially during emergency response, and appropriate implementation of the same. During the strategic engagements with partners, joint work plans and a common results framework was developed. MIYCN was included as contributing to the larger framework, which involved building and sustaining basic MIYCN structures (network of MIYCN counsellors, mother-to-mother support groups, referral structures and minimum reporting) and integration of MIYCN into mainstream health and nutrition interventions. The idea was that if basic structures (as detailed above) are functioning effectively and MIYCN is mainstreamed in health and nutrition interventions and finally integrated across the sectors, optimal MIYCN outcomes that can be sustained will be achieved. Discussions were held (and are ongoing) on whether to conduct a knowledge, attitudes and practice (KAP) assessment separate from the annual UNHCR SMART (Standardised Monitoring and Assessment of Relief and Transitions)/SENS (Standardised Expanded Nutrition) surveys, due to challenges faced in monitoring MIYCN indicators during the annual survey. ACF designed and set up a robust and reliable M&E (monitoring and evaluation) system to effectively track and report MIYCN outputs and outcomes for MIYCN programmes. Data collection tools for monitoring IYCN activities (largely process indicators) both at the community and health facility levels were jointly developed with partners in consultation with UNHCR and UNICEF. In addition, joint supervision was conducted by UNHCR, UNICEF, ACF and implementing partners across camps to monitor progress of MIYCN integration into routine health and nutrition activities.

Various strategic engagements and discussions were held between ACF, UNHCR and implementing partners to aid in the integration of MIYCN into routine health and nutrition activities for improved health and nutrition outcomes. Capacity-building on MIYCN was conducted with partners to equip them with the necessary skills to protect, support and promote appropriate feeding practices. There was advocacy to partners on allocation of funds for preventive activities such as immunisation, micronutrient supplementation and MIYCN, especially during emergency response, and appropriate implementation of the same. During the strategic engagements with partners, joint work plans and a common results framework was developed. MIYCN was included as contributing to the larger framework, which involved building and sustaining basic MIYCN structures (network of MIYCN counsellors, mother-to-mother support groups, referral structures and minimum reporting) and integration of MIYCN into mainstream health and nutrition interventions. The idea was that if basic structures (as detailed above) are functioning effectively and MIYCN is mainstreamed in health and nutrition interventions and finally integrated across the sectors, optimal MIYCN outcomes that can be sustained will be achieved. Discussions were held (and are ongoing) on whether to conduct a knowledge, attitudes and practice (KAP) assessment separate from the annual UNHCR SMART (Standardised Monitoring and Assessment of Relief and Transitions)/SENS (Standardised Expanded Nutrition) surveys, due to challenges faced in monitoring MIYCN indicators during the annual survey. ACF designed and set up a robust and reliable M&E (monitoring and evaluation) system to effectively track and report MIYCN outputs and outcomes for MIYCN programmes. Data collection tools for monitoring IYCN activities (largely process indicators) both at the community and health facility levels were jointly developed with partners in consultation with UNHCR and UNICEF. In addition, joint supervision was conducted by UNHCR, UNICEF, ACF and implementing partners across camps to monitor progress of MIYCN integration into routine health and nutrition activities.

Having noted the many strategies and approaches to improving MIYCN, there was a need to sustain the established structures and practices through integration into various sectors and adoption of a systematic behaviour change communication (Communication for Development (C4D) model. Formative research as part of C4D was conducted in June 2013 to determine factors influencing (predisposers, reinforcers, facilitators and inhibitors) MIYCN practices in the refugee camps. This found that knowledge on MIYCN among caregivers had generally increased as a result of previous and current MIYCN programing. However, adoption of optimal MIYCN practices, especially early initiation of breastfeeding, exclusive breastfeeding and appropriate complementary feeding, remained sub-optimal and below the universal World Health Organization (WHO) target of 80%. This was mainly attributed to strong cultural beliefs and practices among the refugee population. In addition, it was evident from the assessment that there was a lack of involvement by other sectors in supporting implementation of MIYCN activities, despite the existence of livelihoods; water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH); and child protection projects that could benefit the beneficiaries. A formative research report was formulated, guided by findings from the assessment and focused mainly on MIYCN practices, while delving into cross-cutting influences from other sectors such as health, protection, livelihoods and WASH, among others. This further set the stage for the design of the cross-sectoral C4D strategy that is systematic in achieving positive and holistic behaviour change in the refugee camps by leveraging other sectors.

Achievements realised

- Capacity strengthening of national qualified staff and incentivised staff (largely health) through classroom training, on job training, mentorship programmes and continuous medical education sessions; 80% of both of these cadres were reached. Implementing partners have full capacity to implement MIYCN activities and all camps have MIYCN steering committees that oversee implementation and ensure integration of all activities.

- Community sensitisation of key community members on MIYCN. This included traditional birth attendants; grandmothers; safe motherhood promoters; fathers; youth, religious and community leaders.

- Recipe development sessions and participatory cooking demonstration sessions at block level to improve dietary diversity.

- Intermediate baby-friendly hospital and community initiative (BFHI/ BFCI) assessments and formation of BFHI committees.

- Sensitisation sessions for health workers and community members on the Breastmilk Substitutes (BMS) Act 2012.

- Formation and sustaining of 774 mother-to-mother support groups (MTMSGs) across all the camps, reaching an average of 11,610 pregnant and lactating mothers on a monthly basis.

- Formulation of a communication strategy, including development of key MIYCN messages and Information, Education and Communication (IEC) materials.

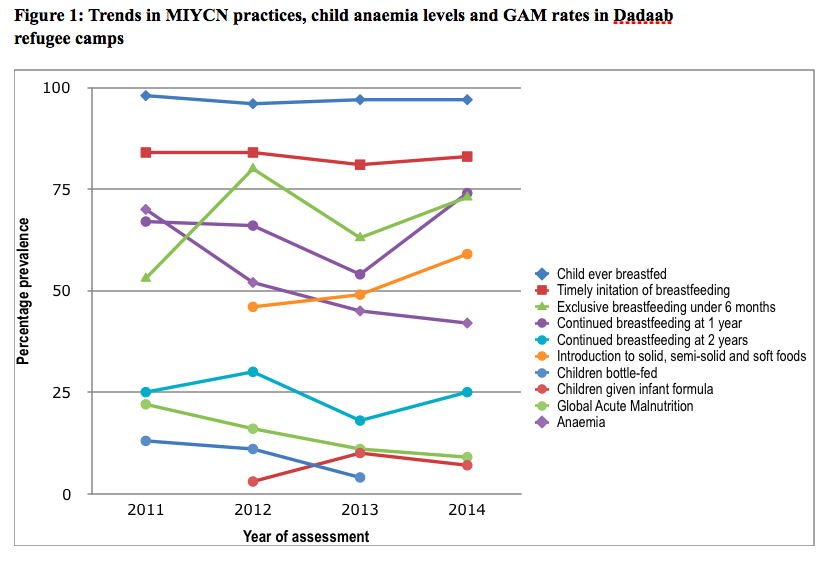

As MIYCN programming was strengthened, MIYCN practices overall improved. Over the same period, GAM prevalence and iron deficiency rate decreased (see Figure 1). It is likely that improved MIYCN practices coupled with improved emergency response interventions (including the general food ration) were key contributors of the improved situation.

As MIYCN programming was strengthened, MIYCN practices overall improved. Over the same period, GAM prevalence and iron deficiency rate decreased (see Figure 1). It is likely that improved MIYCN practices coupled with improved emergency response interventions (including the general food ration) were key contributors of the improved situation.

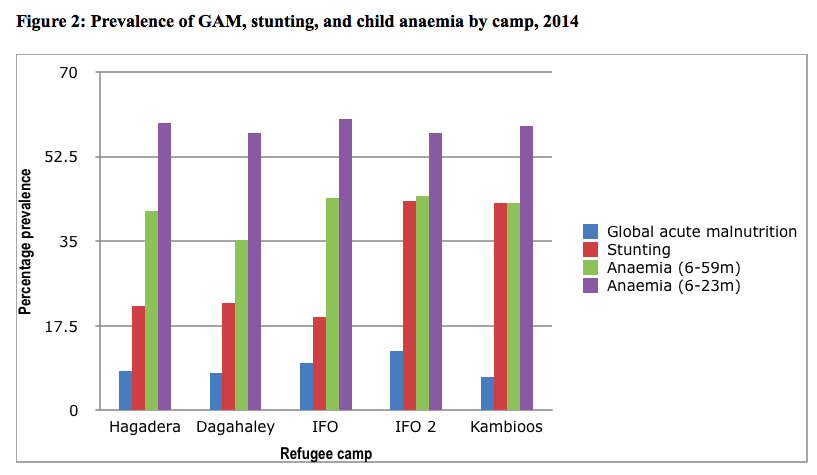

Regarding trends in MIYCN practices reflected in Table 1, a dip in exclusive breastfeeding rates and a rise in infant formula use in 2013 likely reflects the transition period between ACF-led intensive direct implementation in 2012 to partner-led implementation with minimal external support. Anaemia prevalence fell in children aged 6-59 months and pregnant and lactating women; both groups were targeted with micronutrient powders from 2011 to end of 2013. The prevalence of GAM, stunting and anaemia by camp in 2014 is shown in Figure 2.

Implementing recommendations: Bringing dynamics into the mechanics

Implementing recommendations: Bringing dynamics into the mechanics

With support from UNHCR, the project took advantage of various interagency fora to orient sector heads and programme staff on the importance of a multi-sector approach in integration of MIYCN for improved nutritional outcomes. Discussions were held during nutrition technical fora, health and nutrition coordination meetings and head of agency meetings on a monthly basis. In addition, various multi-sectoral workshops were held which led to development of a comprehensive Behaviour Change Communication (BCC) strategy highlighting key activities that facilitate integration of MIYCN into other sectors. The approach used was to link women engaged in MTMSGs as channels for dissemination of MIYCN behaviour-change communication to other sectors, programmes and interventions. The project took advantage of various interagency fora to orient various sector heads and staff on the importance of a multi-sector approach to integration of MIYCN for improved feeding practices and hence nutrition status. The Food Security and Livelihoods (FSL) and WASH sectors were some of the active participants and contributors during the process.

For example, MIYCN messages were mainstreamed in FSL programmes, such as fresh food vouchers supported by UN World Food Programme (WFP) aimed at complementing the general food distribution. Through orientation and meetings, the Danish Refugee Council has shown commitment to involve MTMSG members in their ongoing livelihood programmes to equip them with various skills on income-generating activities and village saving associations (VSLAs). This will enable the caregivers be to produce or purchase various foods available in the local markets to improve complementary feeding. It is important for all livelihood partners to support MTMSG members in starting and sustaining cost-friendly activities (such as kitchen gardening) to help improve dietary diversity.

Integration of WASH activities into the MIYCN programme was also evident; all MTMSGs (which have an ultimate nutrition goal) were targeted with hygiene-promotion trainings on proper hand washing, safe water chain, and proper excreta disposal. Potties were provided to mothers with children aged between 12 and 18 months; pot filters (to filter water to remove residue and bacteria) were provided to mothers with children aged 0 to 6 months; while environmental kits for clean-up campaigns were provided to WASH committees who had received training in hygiene promotion.

Integration of WASH activities into the MIYCN programme was also evident; all MTMSGs (which have an ultimate nutrition goal) were targeted with hygiene-promotion trainings on proper hand washing, safe water chain, and proper excreta disposal. Potties were provided to mothers with children aged between 12 and 18 months; pot filters (to filter water to remove residue and bacteria) were provided to mothers with children aged 0 to 6 months; while environmental kits for clean-up campaigns were provided to WASH committees who had received training in hygiene promotion.

UNHCR plans to conduct a KAP assessment by the end of 2016 to determine the progress of the indicators, especially on improvement in appropriate complementary feeding after livelihood integration within mother support groups.

Challenges and lessons learnt during implementation

Key challenges that were faced included:

- There was major focus on treatment activities during the emergency response, which resulted in funding constraints on preventive activities. This reinforces the need to build the case for the effectiveness of preventive interventions in ensuring good health and nutrition outcomes. Active lobbying led to UNHCR allocating funds in the 2014-15 budget for such activities.

- Strong cultural beliefs and practices prevail among the refugee population; these take time to change.

- High levels of insecurity incidents threatened planned implementation of activities in the refugee camps. Frequent insecurity incidents led to disrupted support to incentive workers and MTMSGs at the block level due to cancellation of movements to the block/community level by qualified staff.

Lessons learned during implementation include:

- A communication strategy tailored to address barriers while strengthening facilitator capacity to promote adoption of optimal MIYCN practices is essential to drive social behaviour change. The development of the C4D strategy involving all stakeholders and community members enhances ownership and participation of other actors. This is essential in changing practices in a sustainable manner.

- Building capacity and involvement of key influencers, such as men, grandmothers and mothers-in-law, is important in influencing optimal MIYCN practices, rather than concentrating only on pregnant and lactating women.

- Full participation of the refugees in the project is vital to the success of behaviour change activities; the refugee community needs to be fully involved in the planning and implementation of MIYCN interventions. Examples of such involvement in this project include selecting mentor mothers; recruitment of incentive MIYCN counsellors; the community providing project insight during community dialogues; fathers supporting mothers; religious leaders mobilising the community during prayers; and shopkeepers scaling down the sale of infant formula to mothers.

- In addition to continued active participation in health and nutrition, there is a need to expand participation to other sectors such as water, sanitation, child protection, education, livelihoods, and shelter and protection. These sectors can provide a supportive structure for influencing MIYCN practices.

- Mothers base their infant feeding decisions on an array of factors, including their experiences, family demands, socioeconomic circumstances and cultural beliefs; hence these all affect optimal MIYCN practices. Maternal adherence to the WHO recommendations on MIYCN have also been found to be influenced by a host of other different and often inter-relating factors, including parental age, personality and educational attainment. In addition, the child’s birth order in relation to other siblings and the influence of health professionals may also contribute to maternal behaviour.

Conclusions

The observed reduction in GAM rates is attributable to an improvement in emergency response interventions generally which involves an emergency service package of health, food security, protection, nutrition and livelihoods. However, amongst these MIYCN was singled out as a major preventive factor. Dadaab refugee camps were chosen in May 2015 to pilot the IYCF-friendly framework (see field article in this edition of Field Exchange). The pilot framework, led by UNHCR and Save the Children, will support MIYCN mainstreaming across sectors by creating momentum around IYCF and the framework, initiating collaboration and engagement from other sectors and strengthening the capacity of key IYCF actors to take the framework forward. To date, sector heads and staff from child protection, livelihoods and health have been oriented on the framework and have committed to implement activities that can be integrated into their sector interventions. WASH, education, and protection and shelter, among other sectors, will be prioritised in phase two of orientation, after child protection and livelihoods are judged to have been sufficiently engaged. Progress of the action points and commitment by partners from various sectors will be reviewed and discussed during bimonthly coordination meetings led by UNHCR. Discussion on how best to monitor implementation of the framework is ongoing, building on the headway already made by ACF.

For more information, contact: Jacob Korir.