Integrating nutrition products into health system supply chains: making the case

By Thomas Sorensen, Patrick Codjia, Patricia Hoorelbeke, Ed Vreeke and Ingeborg Jille-Traas

Thomas Sorensen is Chief of Supply with UNICEF’s Regional Office in Nairobi. He has been with UNICEF since 1998, initially joining the India Country Office and subsequently UNICEF Supply Division in Copenhagen. Pre-UNICEF, he worked in the vaccine industry and with DANIDA health programmes. He holds a Masters in Economics and Planning and a Masters in Public Health.

Patrick Codjia is Nutrition Specialist with UNICEF’s Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office, and has been based in Nairobi (Kenya) since 2013. Previously he worked for UNICEF in Malawi, DRC and Botswana on development and emergency nutrition. Pre-UNICEF, he worked with an international NGO in Eastern DRC and a research centre in Burkina Faso on nutrition projects.

Patricia Hoorelbeke is Nutrition Specialist with UNICEF, West and Central Africa Regional Office based in Dakar (Senegal) since 2012, and has over 16 years’ experience in development and emergency programming in West Africa. Prior to joining UNICEF, she worked with international NGOs, notably in Niger, in Mali and at regional level.

Ed Vreeke is a senior partner with HERA (www.hera.eu). He consults mainly on pharmaceutical procurement and supply-related issues. He is a former director of Asrames (www.asrames.com) in the DRC. He holds a Masters in Economics from Tilburg University in the Netherlands.

Ingeborg Jille Traas holds a Masters in Public Health and has over 15 years experience of working in pharmaceutical procurement and supply management, particularly for HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis-related health commodities, and in health systems strengthening.

The authors extend special thanks to UNICEF country office colleagues who initiated the country reviews which formed the basis for the consolidated review and this article. Thanks also to everyone met or interviewed by phone and Skype for their time and readiness to share their knowledge and ideas.

Location: Global

What we know: Integration of acute malnutrition treatment services into health systems is a common aim; typical considerations include health worker capacity, management systems, governance and funding. In contrast, nutrition product supply chains typically run parallel.

What this article adds: UNICEF conducted eight country studies on nutrition product supply chains in sub-Saharan Africa. By consolidating these and supplementing them with primary and secondary data from other studies and semi-structured interviews with global and national level stakeholders, a number of findings have been revealed. Parallel supply chains are typically managed by development partners, often via UNICEF, especially in emergencies, and may be donor-driven in the interest of efficient delivery. As a result, government may be less accountable for reaching public health results and supply chain resources may be stretched. Dependence on short-term emergency funding for supplies hampers longer-term planning. Integration of product supply into national medicine supply chains is desirable, and most likely achievable in non-emergency settings. Such integration is an important step to scale up and sustain the treatment of severe acute malnutrition and is a critical dimension of health systems strengthening that requires investment to manage the transition.

Background

The attention to combatting undernutrition continues to grow, with an increasing number of organisations and alliances involved in nutrition and food security programmes in health, education, water and sanitation, and agricultural sectors. The long-term effects of undernutrition on economic development are, increasingly, better documented and understood. The introduction of Community-based Management of Severe Acute Malnutrition (CMAM) early in this century was made possible by the introduction of Ready to Use Therapeutic Food (RUTF) and Mid-Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC), and facilitated the scaling-up of treatment of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) at the health facility and household levels. From a programmatic point of view, the scale-up of CMAM has been successful in that it has been accepted as an integral part of the primary healthcare basic services package by most, if not all, governments. Full integration of the corresponding supply chain system is, however, pending in most countries.

The attention to combatting undernutrition continues to grow, with an increasing number of organisations and alliances involved in nutrition and food security programmes in health, education, water and sanitation, and agricultural sectors. The long-term effects of undernutrition on economic development are, increasingly, better documented and understood. The introduction of Community-based Management of Severe Acute Malnutrition (CMAM) early in this century was made possible by the introduction of Ready to Use Therapeutic Food (RUTF) and Mid-Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC), and facilitated the scaling-up of treatment of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) at the health facility and household levels. From a programmatic point of view, the scale-up of CMAM has been successful in that it has been accepted as an integral part of the primary healthcare basic services package by most, if not all, governments. Full integration of the corresponding supply chain system is, however, pending in most countries.

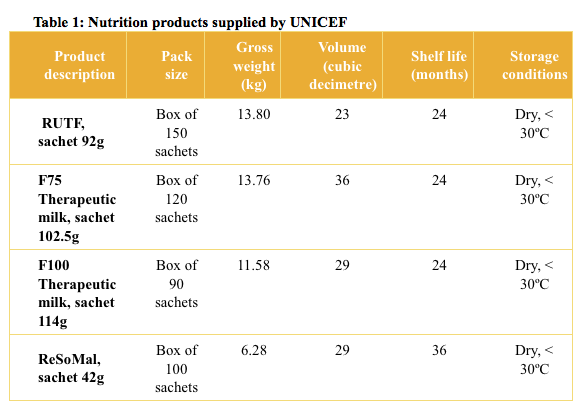

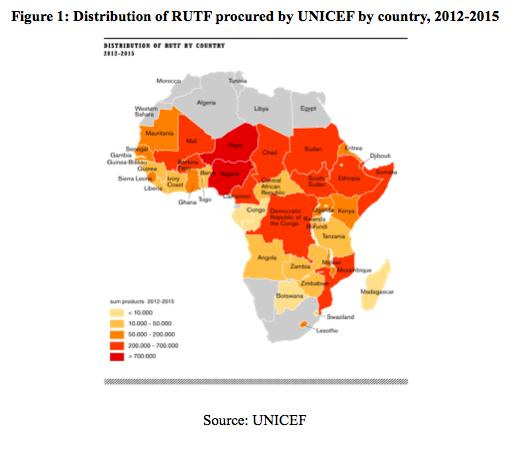

In most sub-Saharan African countries, UNICEF is instrumental in ensuring the supply of nutrition products (see Table 1). In the years 2011-2012 to June 2015, UNICEF procured more than 5.8 million cartons of RUTF, 18,155 cartons of ReSoMal, almost 154,000 cartons of F75 and 140,000 cartons of F100, corresponding to up to six million treatments for SAM. Once procured, these products moved from national level to the health facilities through supply chains that were often largely organised and managed by UNICEF Country Offices and their implementing partners.

In the last 10 to 15 years, UNICEF’s engagement has been rooted in emergency responses at country level and market-influencing strategies focusing on building local RUTF production capacity (Komrska et al, 2013). From 2013 onwards, a number of UNICEF Country Offices have initiated reviews, independent of one another, to inform how they can either optimise existing supply chains or integrate them into the national supply chain systems.

This article provides an empirical contribution to the understanding of how supply chains for nutrition products function in large parts of sub-Saharan Africa. The primary source of data arrives from the results and analysis of eight UNICEF country studies. Supplemented with primary and secondary data from other studies and semi-structured interviews with global and national level stakeholders, it provides insight into and guidance on what it takes to move parallel emergency-driven supply chains into the national supply chain for medicines and health products.

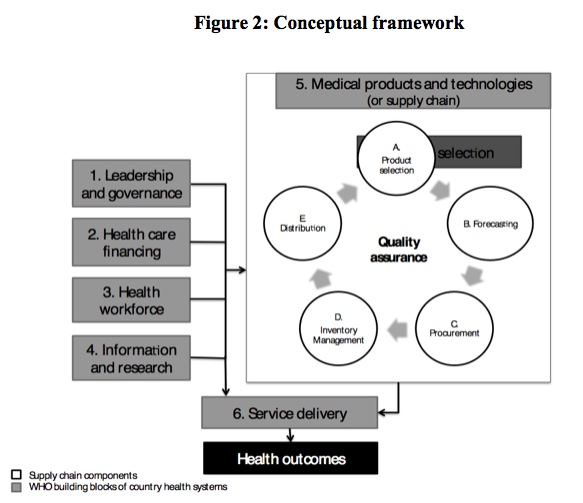

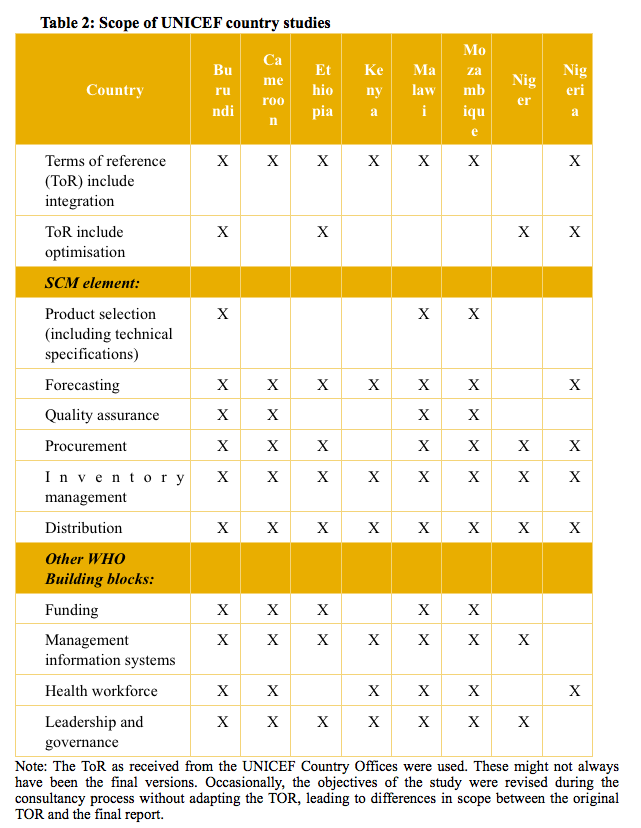

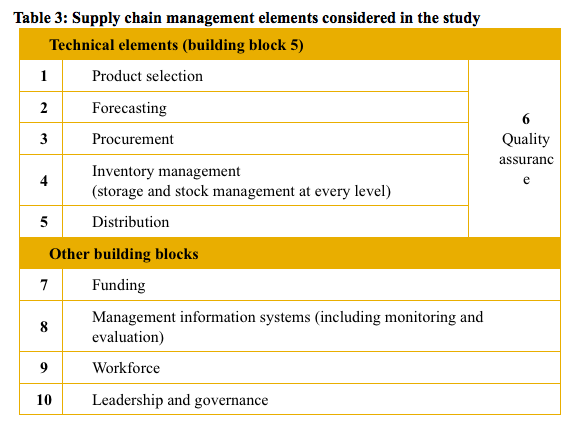

Conceptually, the core analysis is based on the WHO building blocks for health systems strengthening (Figure 2). As such, the underlying assumption is that any sustainable integration of nutrition supply chain management (SCM) systems requires carefully thought-through interaction with the other interrelated health system components. Tables 2 and 3 reflect the scope of the country studies and which SCM elements and other WHO health systems-building blocks were included as part of the study.

Findings

For various historical stop-gap reasons, development partners have taken the lead in delivering life-saving commodities in the different countries. In many cases, development partners (mainly UNICEF) are responsible for all or parts of the supply chain for nutrition products. Nutrition products are therefore often seen by government health staff at all levels as ‘external’ products. Integration of the nutrition products supply chain in the regular supply chain is an important contribution toward normalisation of these products. A key element for ‘normalisation’ of nutrition products is inclusion on the National Essential Medicine List, which is seen as an important driver for inclusion in other SCM elements.

Whether focusing on optimisation or integration, predictability and availability of funds necessary for correct execution of the different SCM elements continues to be a major obstacle in all assessed countries.

De facto integration has often taken place downstream in the supply chain (district and facility level). Where integration is taking place, it is done incrementally, element by element.

For full integration to take place, the need for health systems strengthening efforts becomes inevitable. However, funds for system strengthening interventions are not easily available, especially within nutrition programmes. Most nutrition-related funding is focused on procurement and programme issues. It is mobilised via donors and is often linked to emergency response or preparedness. This makes general supply chain planning and long-term integration efforts difficult.

We found that integration is often limited to integrating the storage and distribution elements, while other SCM elements (see Table 2) are overlooked. Thorough knowledge and awareness about the full supply system and its linkages to the broader health system contributes to better prospects for sustainable results.

Most major nutrition-funders indicated that they support integration initiatives and are willing to invest in the necessary health systems strengthening, even when these are not directly linked to the nutrition programme. At global and regional levels, a number of initiatives exist to facilitate integration. At country level, a large variety of integration processes are ongoing, often for parallel supply chains linked to the HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis programmes. Several opportunities for support to health system strengthening activities exist, often through global health initiatives such as The Global Fund (designed to accelerate the end of AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria as epidemics), The Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization, and The Power of Nutrition.

Discussion

Evidence on the efficiency and efficacy performance of regular and parallel supply chains remains limited. Parallel supply chains, however, have a tendency to compete for scarce supply chain resources for other medicines and health products, making the larger public health system less efficient. If managed by development partners, this will have a tendency to make the development partner accountable for reaching public health results, rather than the government system and its elected representatives. Parallel supply chains also tend to increase overall management costs.

New strategies, such as rendering the Central Medical Stores (CMS) more independent from governments and outsourcing one or more SCM elements to the private sector, are changing the traditional national supply chains and offer additional opportunities for integration. But the CMS can be expected to continue to play a key role in the SCM of medicines and health products in the public sector for the foreseeable future. The exact configuration of a national supply chain will, however, be country and context-specific.

Analysing enablers and bottlenecks from the eight country studies on RUTF SCM, it is clear that actions to strengthen health systems, of which the supply chain is part and parcel, are time-consuming processes that require substantial funding and long-term commitment from all stakeholders involved. Health systems strengthening can best be achieved by taking small steps and by building on existing systems.

Further, when embarking on an integration process of a parallel supply chain for nutrition products, the following elements are crucial:

- A clear vision of the process shared by all stakeholders and endorsed by the government;

- The leadership of the government;

- A thorough situation analysis taking into account all SCM elements and linkages to the other health system building blocks; and

- Description of the implementation process, based on the situation analysis, accompanied by a plan of action with milestones, timelines, required resources, stakeholders’ roles and responsibilities, implementation challenges and their mitigation measures.

The following elements are important for the success of the implementation process:

- A functional management organisation in charge of regular supply chain management that is able (with or without strengthening efforts) and willing to take over one or more elements of the parallel SCM;

- The Ministry of Health in a leadership role;

- A ‘champion’: ideally an organisation with sufficient resources, adequate experience in nutrition and/or SCM, a good track record and convening capability attracting all main stakeholders;

- A functional coordination mechanism in which all organisations involved in nutrition and/or SCM are represented;

- Close monitoring of the process by a joint stakeholder committee; and

- Access to dedicated technical assistance, if considered necessary.

Conclusion

This study found that RUTF SCM integration processes almost always lead to a need for health systems strengthening. This is confirmed by the limited results from the literature review. When considering an integration process, all SCM elements, as well as the other health system building blocks (funding, management information systems, workforce and leadership and governance) have to be considered. When embarking on an integration process, a step-wise approach is advisable, and actors involved should realise that an SCM change process is an iterative process, with the unavoidable ‘fail and learn’. Integration should not be pursued at any cost; what is possible depends on the context. It can be full integration, partial integration or optimisation of the existing parallel supply chain. Strengthening of the regular supply chain should always be taken into account in the planning and budgeting of the integration process.

For more information, email Patrick Codjia or Thomas Sorensen

General reference is made to the original and comprehensive UNICEF Nutritional Supply Chain Integration Study, which can be accessed at Supply Chain for Children, www.supplychainforchildren.org/

References

Komrska J., Kopczak L.R., Swaminathan J.M., (2013). Supply Chain Management Review, When Supply Chains Save Lives. January/February 2013. See www.scmr.com