Nutrition Impact and Positive Practice: nutrition-specific intervention with nutrition-sensitive activities

By Sinead O’Mahony and Hatty Barthorp

Sinead O’Mahony is the NIPP Global Project Manager and a member of the Technical Team of GOAL Global.

Hatty Barthorp is Global Nutrition Advisor and a member of the Technical Team of GOAL Global.

The authors would like to thank the GOAL health, nutrition, and monitoring, evaluation, accountability and learning (MEAL) teams across the five countries where NIPP is implemented (Malawi, Zimbabwe, Niger, Sudan and South Sudan); particularly Muchadei Mubiwa, Chipo Tafirei, Jimmy Harrare, Gift Radge, Lemma Debele, Sara Ibraham Nour and Araman Musa and their wider teams for their ongoing dedication to the NIPP approach implementation and learning process. We would also like to acknowledge Alice Burrell, who conducted the NIPP research quoted in this article and the Malawi and Zimbabwe Nutrition and MEAL teams who facilitated this research.

Location: Niger, South Sudan, Sudan, Malawi and Zimbabwe.

What we know: Nutrition Impact and Positive Practice (NIPP) is a participatory ‘circle’ approach developed by GOAL that uses positive deviance implemented by trained volunteers in short cycles (2-12 weeks) to improve nutrition security and care practices of households prone to malnutrition.

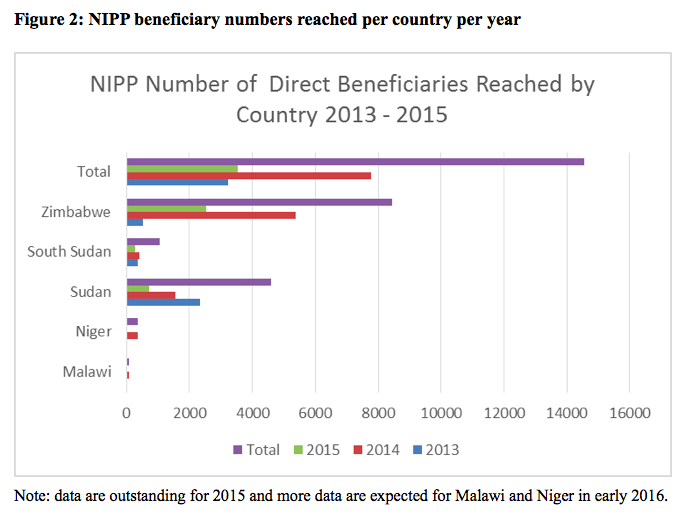

What this article adds: Since 2013, the approach has reached 14,000 beneficiaries in Niger, South Sudan, Sudan, Malawi and Zimbabwe. NIPP has been successful in treating mild and moderate malnutrition; outstanding moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) cases have continued to recover for up to six months post-discharge, suggesting sustained positive practices. Stigma and time constraints have contributed to high default rates (28%) in pregnant and lactating women (PLW). There is good uptake of nutrition, WASH, livelihoods and health knowledge and practices. Knowledge of nutrition, health and hygiene behaviours is maintained post discharge; WASH and livelihoods positive behaviours decline (under research). Low male engagement has improved with innovation. Extended Nutrition Impact and Positive Practices Approach (eNIPPa) has been developed, linking more closely to agriculture and biofortification. Pilots are taking place in urban settings and in other contexts measuring impact on chronic malnutrition and being implemented alongside cash transfers. Further scale-up and a continued research programme is planned for 2016.

An article introducing the NIPP concept when it was first being piloted was published in Field Exchange, issue 47 (Chisnau, Okello, Nour et al, 2014). This article presents an update on the rollout and implementation of NIPP over the past 18 months since this article was published.

What are NIPP circles?

NIPP circles are gatherings of male and female community members who meet on a regular basis for up to 12 weeks to share and practice positive behaviours. NIPP circles aim to improve the nutrition security and care practices of households either affected by, or at risk of suffering from, malnutrition through participatory nutrition/health learning (including hygiene-sanitation) and diet diversity promotion. The circles aim to facilitate knowledge and skills sharing of both men and women using locally-available resources. Circles use discussion, practical exercises and positive reinforcement to help families adopt sustainable, positive behaviours. The concept is focused around there being easy and viable solutions accessible to all participating families.

Through formative research, the NIPP approach identifies key causes of malnutrition within the community. It then uses positive deviance to find parents or caretakers from well-nourished but equally poor households and harnesses and hones their knowledge of successful behaviours and practices, reinforces them and provides a forum in which to transfer them to households with ‘at-risk’ members, such as those with undernourished children. To promote sustainability, NIPP circles use trained volunteers from positive deviant households in the communities who facilitate a series of fun, interactive and engaging sessions using peer-led education to induce and reinforce positive behaviour change and replace negative practices.

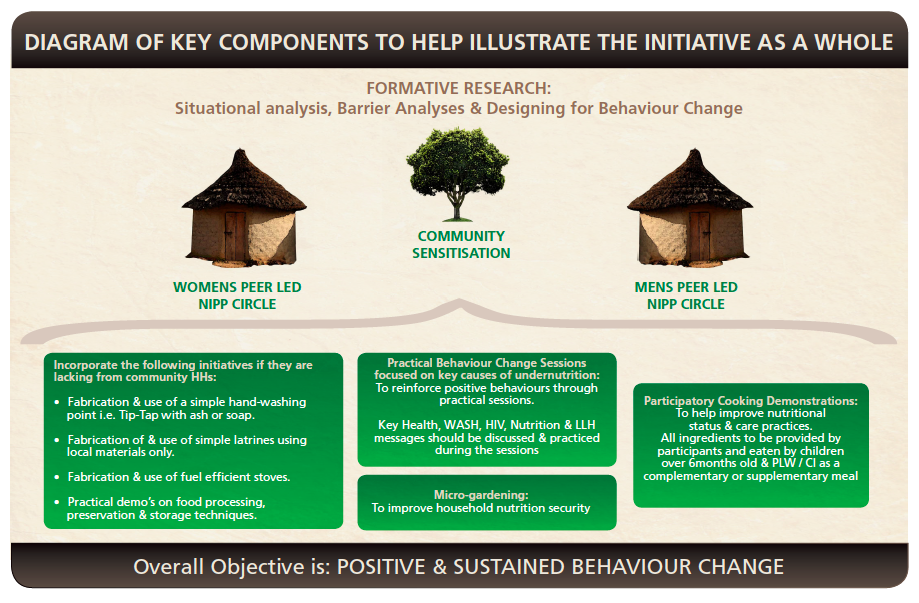

To ensure a holistic approach, the NIPP model is multi-sectoral and covers nutrition-sensitive topics including health, hygiene, sanitation and small-scale agricultural issues. NIPP provides participants with knowledge and skills through three main components, including a package of ‘must-have’ or ‘non-negotiable’ extras:

- Practical Behaviour Change Sessions – focused on key causes of malnutrition for improved awareness and practice. These sessions also include the ‘non-negotiable’ activities: if any of the following initiatives are absent from communities, circle participants will cover manufacture and use of local hand-washing facilities with soap or ash; manufacture and use of simple latrines using local materials only; manufacture and use of fuel-efficient stoves; practical demonstrations on food processing, preservation and storage and any other feasible and useful initiatives, such as drying racks, rubbish pits, etc. Lastly, all participants are requested to bring health/vaccination/growth monitoring cards (children and mothers) for promotion and support for timely health-seeking behaviour;

- Micro-gardening – for improved household nutrition security; and

- Participatory Cooking Demonstrations – for improved nutritional status, feeding and care practices.

(See Figure 1 below for an overview of the key components of NIPP circles approach)

It is understood in many cultural settings that women are often not the sole decision-makers with respect to family food, household sanitation and hygiene, childcare and family feeding practices, etc. although they are often the primary implementers. Men, mothers-in-law, elders, traditional healers, community leaders, religious heads and others all play a role in determining what are deemed acceptable practices within a community. Consequently, NIPP circles not only address women (as primary carers), but also engage others who play influential roles in their day to day life. Therefore, each ‘macro circle’ is broken down into three separate circles which are tailored individually to both female and male representatives of targeted households, with a separate circle for key community figures. By maximising transparency, we can try to ensure understanding and acceptance of new behaviours and/or changes to household routines. This will help to maximise results of sustained, positive behaviour change.

The duration of circle cycles and session length are based on flexible timeframes to best suit the context and the participants. It is possible for short-cycle projects (i.e. two weeks) to be run daily, linked to facility-based nutrition programmes with a rapid turnover, i.e. community management of acute malnutrition or growth-monitoring promotion programmes. Conversely, circles might be run on 12-week cycles, meeting three times a week; this is the most common modality of implementation used by GOAL country programmes.

NIPP includes an extensive monitoring and evaluation package as well as an auto-calculating database, which enables implementing teams to see the outputs and outcomes of the programme immediately as they enter the data. This extensive monitoring and evaluation package also includes 12-month longitudinal follow-up periods of a representative sample from each geographical area per year. This longitudinal data helps monitor and provides evidence of the continued adoption of positive behaviours and maintenance of nutrition outcomes at two, six and 12 months post-graduation from the NIPP circle.

NIPP rollout, outputs and outcomes to date

Since NIPP was last described in Field Exchange, it has grown rapidly and has expanded into two more countries; it is now implemented in Niger, South Sudan, Sudan, Malawi and Zimbabwe. Since 2013, the approach has reached over 10,000 female and 4,000 male beneficiaries (see breakdown by country in Figure 2). This article reports on data for 9,852 female beneficiaries and 4,172 male beneficiaries available for analysis at the time of writing.

Box 1: Admission categories for NIPP circle

- Infants <2 months who are visibly thin

- Infants 2-5.9 months with a MUAC < 11.0cm

- Children 6-59 months with a MUAC between 11.5-12.4cm (MAM)

- Children 6-59 months with a WFH (% or z-score) referred from a health clinic (MAM)

- Children 6-59 months with a WFA < 80% on the Road-to-Health chart (underweight)

- Children 6-59 months with a H/LFA < 80% on the Road-to-Health chart (stunted)

- Children any age referred from an OTP (non-MAM)

- PLW with MUAC <23.0cm (MAM)

- Others: PLW with MUAC ≥23.0cm (non-MAM)

- Others: chronically ill (not malnourished)

- Others: twins/triplets (not malnourished)

- Others: interested carers with no children <60 months (not malnourished)

- Others: children <60 months with interested carers (not malnourished)

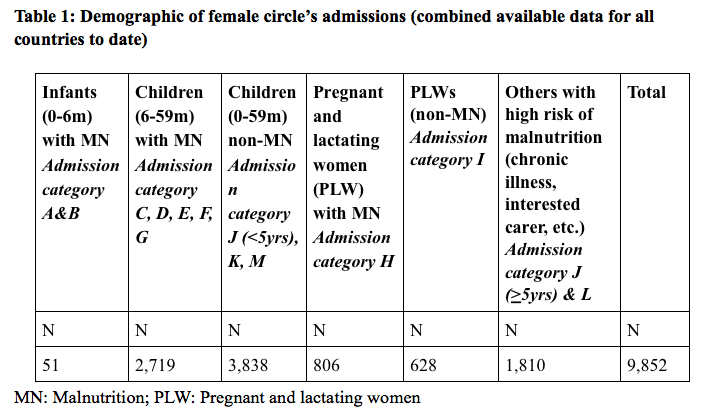

NIPP has a wide admissions basis with 13 categories, including infants, children and women either suffering from some form of malnutrition or deemed at risk, the purpose of which is to ensure all those who are vulnerable to malnutrition in the community are included in the programme. Caregivers who wish to participate irrespective of a child’s nutritional status may also do so. The breakdown of admission categories of female beneficiaries can be seen in Table 1.

Cases of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) that are identified are referred to the existing Outpatient Therapeutic Programme (OTP). Where no programme is available for the treatment and management of MAM, any identified cases during community screening are referred to the NIPP programme. MAM admission criteria to the NIPP circles are:

- Children 6-59 months with MUAC 11.5cm - <12.5cm or with WHM <80% referred from a health facility or with WA <80% or growth faltering on their ‘road to health’ chart;

- All children recently discharged cured from OTP (may include children >59m);

- Infants two to six months with MUAC <11cm with appetite;

- Infants under two months visibly thin but with appetite;

- Malnourished PLW (MUAC <23cm – cut-offs may vary by country as per national guidelines).

Discharge criteria are: MUAC ≥12.5 cm for children 6-59 months; MUAC ≥11 cm for infants two to six months; improved nutritional status for infants under two months on ‘road to health’ charts (verified at health facility) at the end of the of NIPP Circle cycle; MUAC ≥23 cm for PLWs. For all discharges and for families with chronic illness, etc., carers/PLW must pass the post-test assessment (includes theory and practical elements).

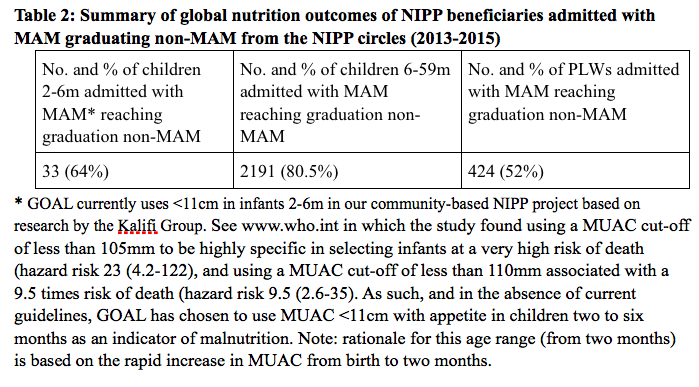

As a result, we have noted that NIPP is successful in treating mild and moderate malnutrition. We believe this is due to improved care practices in the home, coupled with the extra meal available through the cooking-demonstration activity at every NIPP circle meeting to children who attend the circle with their carer. The nutrition outcomes of beneficiaries registered with MAM can be seen in Table 2; 80% of children between six and 59 months admitted to NIPP with MAM were discharged cured at the end of the three-month intervention. If they do not ‘recover’, households are eligible and invited to participate in another cycle if appropriate, or indeed referred for more specialist support to government support programmes/structures as appropriate. During the six months after discharge, the numbers of MAM cases in the follow-up group continued to decline from 29 cases at graduation to 13 cases at two months follow-up and four cases at six months follow-up. As very few among those discharged with MAM post-graduation were lost to follow-up, this continued decrease in MAM numbers could be attributable to continued practice of positive behaviours in the household.

The cure rate of PLW with MAM admitted to the circles is 52%. PLWs with MAM have the highest rate of default in the programme (28%) in comparison with other female admission categories; over the past six months, this has been investigated through qualitative research in Zimbabwe and Malawi. The findings have identified stigma and time constraints as main causes of default in this admission group. GOAL will begin to trial new ways of supporting this group to try and improve these default rates in 2016.

The cure rate of PLW with MAM admitted to the circles is 52%. PLWs with MAM have the highest rate of default in the programme (28%) in comparison with other female admission categories; over the past six months, this has been investigated through qualitative research in Zimbabwe and Malawi. The findings have identified stigma and time constraints as main causes of default in this admission group. GOAL will begin to trial new ways of supporting this group to try and improve these default rates in 2016.

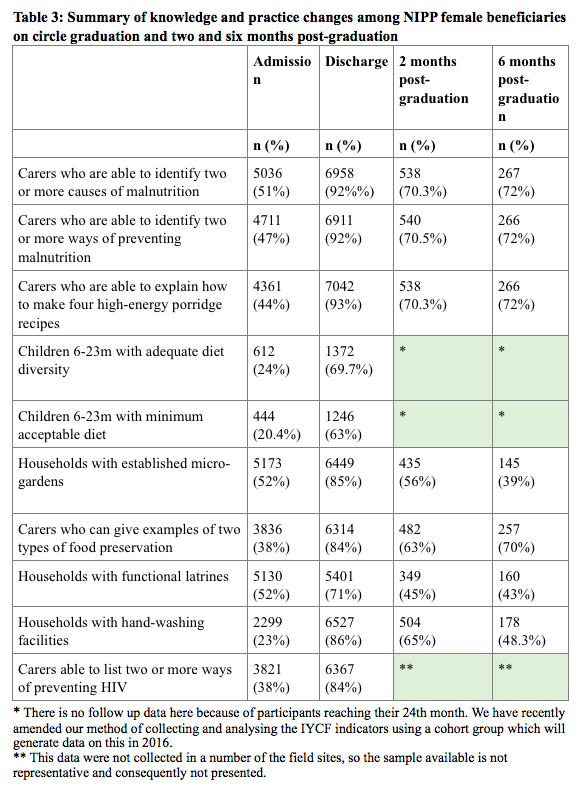

During this scale-up of NIPP over the past 18 months, we have continued to see a positive impact on nutrition, WASH and health practices. Table 3 provides a summary of the key changes in nutrition, WASH and health knowledge and practices of female beneficiaries and their households assessed before and after completing the 12-week NIPP circle. Table 3 also shows the extent of maintenance of behaviour adoption of some positive behaviour at two and six months post-graduation of a representative sample of NIPP beneficiaries.

The monitoring and evaluation data we have collected for NIPP to date are showing a good uptake of nutrition, WASH, livelihoods and health knowledge, and a strong adoption of positive behaviours over the three months from admission to graduation. During the two and six month follow-up periods, while the knowledge of nutrition, health and hygiene behaviours is being maintained, there is a decline in the continued adoption of some positive behaviours, particularly from the WASH and livelihoods side. The observed fall in households with established micro-gardens is likely a result of seasonal fluctuations. The fall-off in sample size between the two-month and six-month data may be affecting representation of this and other data for the whole NIPP data population. We expect to have a representative sample for 12 months’ follow-up by mid-2016 and further longitudinal data from country programmes in the coming six months.

Adoption of positive behaviour remains around the 40% mark at six-month follow-up for WASH and livelihood activities (the presence of hand-washing facilities is taken as an indirect measure of hand-washing practice). In order to gain a better understanding of the regression in positive behaviours, GOAL has started to design a mixed-methods study which is expected to take place in 2016. In mid-2016, we expect to have a representative sample of 12-month follow-up data which will further inform understanding of behaviours at 12 months.

NIPP lessons learned in 2015

Over the past 12 months of scaling up the NIPP approach and expanding the approach into new countries, a number of lessons have been learned.

Firstly, male engagement has been a challenging element of the NIPP programme. As household health and nutrition are not always seen as issues for men to consider in the majority of the NIPP implementing contexts, ‘hooks’ and incentives to garner improved interest are needed to attract men to participate. Country programme review workshops and some recent qualitative research are informing the NIPP strategy for male engagement. The results have been positive; for example, following a lessons-learned review in Zimbabwe on male engagement in December 2014, male engagement has increased from 10% of female engagement in 2014 to 36% of female engagement in 2015. In 2016 we plan to do further research and learning on male engagement in the NIPP programme.

In 2015, the NIPP approach was adapted for implementation as a nested activity within a livelihoods programme in Zimbabwe which focused on agriculture and biofortification. The adapted version of NIPP is called the Extended Nutrition Impact and Positive Practices Approach (eNIPPa). This approach uses the same implementation framework as NIPP, i.e. volunteers, macro circles and the inclusion of non-negotiable activities. eNIPPa differs in that it is held over a longer period of time (24 weeks vs. 12 weeks), with contact points reduced to once per week instead of two to three times per week. The eNIPPa approach ties in with the agricultural calendar, providing participants with information on seasonally-available foods for cooking demonstrations, food processing techniques and post-harvest management. It also provides information and education on the nutritional impact of biofortified crops being grown in the programme. eNIPPa includes a strong monitoring and evaluation framework. It is expected that the first evidence on the outcomes of the approach will be available in early 2016.

Over the past year, there has been extension of the NIPP circles post-gradation into other community groupings, such as Village Savings and Loan Association and income-generation activities. There have been a number of IGA examples from different countries as a result of the cohesion of groups and skills women learn from the NIPP circles, including building fuel-efficient stoves for other village households in Zimbabwe and selling preserved foods in Sudan.

Finally, in 2015, a number of new NIPP implementation methods were piloted. Lessons learned include measuring the rate and progression of chronic malnutrition (stunting) in children aged six-59 months of NIPP beneficiary households; bringing NIPP to scale in Sudan; NIPP in the urban setting in Zimbabwe; using the Habinaye System (a sustainable small livestock-breeding programme based on the initial injection of a quota of livestock to target households who pass on offspring to subsequent target homesteads) to improve diet diversity in Niger; implementing Community Led Total Sanitation through the NIPP WASH component in Zimbabwe; and implementing NIPP alongside a cash-transfer response to the floods in Malawi. More detailed information from each of these interventions is available from GOAL.

NIPP achievements over the last 12 months

Aside from implementation scale-up, there have been a number of achievements using the NIPP approach over the past 12 months, due to the hard work of the teams implementing the approach in the field. NIPP is now incorporated into the Government of Sudan National Guideline for the Management of MAM as a preventative nutrition approach and GOAL is working with the Federal Ministry of Health to bring NIPP to scale across Sudan. NIPP also featured in the technical resource guide Enhancing Nutrition and Food Security during the First 1,000 Days through Gender-sensitive Social and Behaviour Change as a strong gendered approach for health and nutrition programming. GOAL has engaged with a number of universities to scale up the research element of NIPP to continue the proof-of-concept phase of this preventative nutrition approach. An abstract on the approach was presented at the Development Studies Association of Ireland Annual Conference in 2015 and has been selected for presentation at the International Social and Behaviour Change Communication Summit in Addis Ababa and the Innovation in Global Health conference at Yale University, USA.

Aside from implementation scale-up, there have been a number of achievements using the NIPP approach over the past 12 months, due to the hard work of the teams implementing the approach in the field. NIPP is now incorporated into the Government of Sudan National Guideline for the Management of MAM as a preventative nutrition approach and GOAL is working with the Federal Ministry of Health to bring NIPP to scale across Sudan. NIPP also featured in the technical resource guide Enhancing Nutrition and Food Security during the First 1,000 Days through Gender-sensitive Social and Behaviour Change as a strong gendered approach for health and nutrition programming. GOAL has engaged with a number of universities to scale up the research element of NIPP to continue the proof-of-concept phase of this preventative nutrition approach. An abstract on the approach was presented at the Development Studies Association of Ireland Annual Conference in 2015 and has been selected for presentation at the International Social and Behaviour Change Communication Summit in Addis Ababa and the Innovation in Global Health conference at Yale University, USA.

NIPP Next Steps, 2016

In 2016, GOAL plans to continue to scale up the NIPP approach in country programmes where curative health and nutrition programmes are being implemented. GOAL will also continue building the evidence base around NIPP as both a curative and preventative nutrition approach. A number of studies are planned for 2016, the largest of which is an Impact and Cost Effectiveness Study to Measure NIPP as a Preventative Nutrition Approach for Acute and Chronic Malnutrition. Finally, the NIPP toolkit is currently under review and will be made widely available for implementation by other actors in 2016.

For more information, contact: Sinead O’Mahony or Hatty Barthorp

References

Chishanu, V., Okello, A. F., Nour, S. I.,Barthorp, H. and Connell, N. (2014). Nutrition Impact and Positive Practice (NIPP) Circles. Field Exchange 47, April 2014. p43. www.ennonline.net