Increasing nutrition-sensitivity of value chains: a review of two Feed the Future Projects in Guatemala

By Alyssa Klein

Alyssa Klein is a food security and nutrition specialist with JSI Research & Training Institute on the Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) project. Alyssa’s academic and technical background is in international development and community nutrition and she has an interest in the integration of agriculture and nutrition.

This study was funded by the USAID SPRING project, with additional funding from the USAID Mission in Guatemala. SPRING would like to thank the Rural Value Chains projects implemented by AGEXPORT and ANACAFÉ for facilitating this research and for practical and logistical support. Special thanks to Ricardo Pineda, the primary consultant, who supported the development of the review protocols and field work; and to SPRING colleagues who provided critical feedback. Finally, many thanks to USAID/Guatemala for support throughout the duration of the work.

This study was funded by the USAID SPRING project, with additional funding from the USAID Mission in Guatemala. SPRING would like to thank the Rural Value Chains projects implemented by AGEXPORT and ANACAFÉ for facilitating this research and for practical and logistical support. Special thanks to Ricardo Pineda, the primary consultant, who supported the development of the review protocols and field work; and to SPRING colleagues who provided critical feedback. Finally, many thanks to USAID/Guatemala for support throughout the duration of the work.

This article draws on the following report: SPRING (2015). Increasing Nutrition Sensitivity of Value Chains: A Review of Two Feed the Future Projects in Guatemala. Arlington, VA: USAID/SPRING project. Click here.

Location: Guatemala

What we know: The effect of agriculture on nutrition may be leveraged in many ways through income, production and empowerment of women and is influenced by the environment.

What this article adds: A qualitative study by SPRING examined USAID agriculture value-chain activities in two Guatemala projects to explore impact assumptions and investigate ways to improve nutrition sensitivity. Expected increased income has not (yet) materialised for coffee (annual income) and green beans (saturated market) value chains. Handicrafts value chain reported increased income and demand (with some associated challenges identified). Soil erosion, deforestation and lack of water were reported as large constraints. Identified opportunities to improve nutrition-sensitive outcomes included improved labour-saving technologies (affecting women’s time), expanded messaging on feeding practices, improved childcare services, and expanded markets.

Introduction

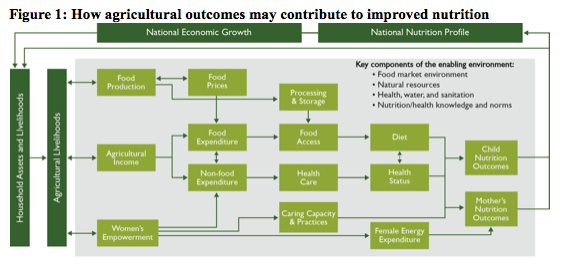

Agricultural livelihoods affect nutrition of individual household members through multiple pathways and interactions. The conceptual pathways between agriculture and nutrition summarise current knowledge to leverage agriculture to improve nutrition. Figure 1 illustrates how various agricultural outcomes might improve access to food and health care; how they impact and are affected by the enabling environment; and ultimately how they affect the nutrition of women and children.

In general, the pathways can be divided into three main routes at the household level: 1) food production, which can affect the food available for household consumption as well as the prices of diverse foods; 2) agricultural income for expenditure on food and non-food items; and 3) women’s empowerment, which affects income, caring capacity and practices, and female energy expenditure. Acting on all of these routes is the enabling environment for nutrition, including several key components: natural resources, food market and health, water, and sanitation environments; nutrition/health knowledge and norms; and other factors such as policy and governance (Herforth & Harris, 2014).

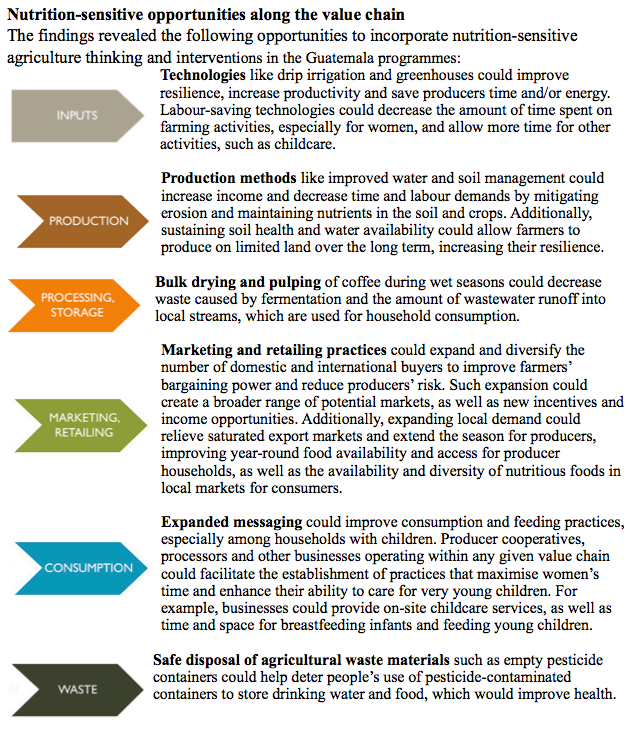

The three starting points in the pathways diagram (production, income and empowerment) represent outcomes of agricultural commodity value chains functioning within the larger food system. Improvements can be made to enhance nutrition outcomes of the value-chain activities, regardless of the selected crop’s nutrition content. Each stage of the value chain and food system – inputs, production, processing, storage, retail, consumption, and waste and recycling (Figure 2) – may present a number of opportunities to enhance nutrition sensitivity.

Context

Chronic malnutrition rates in Guatemala have remained stubbornly high; with 54% of children under five years of age being moderately to severely stunted, the country ranks third-highest in the world for undernutrition (UNICEF, 2009). Among rural and indigenous children in Guatemala, national stunting rates are 59% and 66% respectively. These rates of stunting reach even higher levels in some regions of the Feed the Future zone of influence, which includes 30 municipalities in five departments of the Western Highlands: Totonicapán, San Marcos, Huehuetenango, Quetzaltenango and Quiché (Feed the Future, 2011). As part of its effort to confront the challenge of undernutrition, the Government of Guatemala is implementing a multi-sectoral response through its Zero Hunger strategy and donor support from the Feed the Future initiative. In Guatemala, Feed the Future applies the value-chain approach to transition families out of poverty and improve both their incomes and access to food. Complemented by improved access to health services, potable water and comprehensive hygiene and nutrition education, agricultural value-chain activities are expected to reduce poverty and improve nutrition for the targeted population.

USAID designed two value-chain projects for income-generation interventions that focused on coffee, handicrafts and horticulture value chains in Guatemala’s Western Highlands. The projects are expected “to improve household access to food by expanding and diversifying rural income and to contribute to improve the nutritional status of families benefited under this programme” (USAID Guatemala, 2011). This is to be accomplished by “expanding the participation of poor rural households in productive value chains, and linking these chains to local, regional, and international markets” (USAID Guatemala, 2011). The focus is especially on female farmers.

Methods

During this qualitative study, which took place in September 2014 as part of a SPRING technical assistance visit, we conducted field visits and consultations with a range of stakeholders, including implementing partner staff, input suppliers and buyers and producer cooperative members. During these interactions we looked for opportunities to reduce or mitigate the underlying causes of undernutrition along the three specific commodity value chains of coffee, green beans and handicrafts. We used the pathways diagram as a framework to organise our findings and provide recommendations based on where current interventions were situated relative to the pathways diagram.

During this qualitative study, which took place in September 2014 as part of a SPRING technical assistance visit, we conducted field visits and consultations with a range of stakeholders, including implementing partner staff, input suppliers and buyers and producer cooperative members. During these interactions we looked for opportunities to reduce or mitigate the underlying causes of undernutrition along the three specific commodity value chains of coffee, green beans and handicrafts. We used the pathways diagram as a framework to organise our findings and provide recommendations based on where current interventions were situated relative to the pathways diagram.

The study included a document review, focus group discussions (FGDs) and key informant interviews (KIIs). Primary data collection consisted of KIIs with the project staff of the prime and sub-implementers. KIIs were also conducted with buyers and suppliers to the surveyed cooperatives. FGDs were held with farmer and producer cooperatives, especially during the coffee and green bean value-chain activities. Around six FGDs were held, with 10-15 participants in each. About 30-40 project staff were interviewed. Most of the FGD and KII participants were men.

An assumption underlying the selection of the value-chain commodities was that, due to the strong export market for these commodities, efforts to strengthen each step of the value chain would result in improved income for the range of actors involved, especially smallholder producers and home-based artisans. It was further assumed that an increase in income would contribute to an improvement in nutritional status among participant households. (The projects do not measure nutritional status; however they are part of the portfolio of projects in the Feed the Future Zone of Influence (FTF ZOI)). As part of the FTF ZOI, stunting will be measured at a population level and all projects are expected to contribute to a reduction in stunting; however they are not being held individually responsible for measuring nutritional status among their own beneficiaries. In other words, the income-to-food and health services purchase pathways would be the primary avenues for linking agriculture and nutrition in these activities.

The export product of green beans was chosen for horticulture because it is one of the two primary crops grown by a majority of project-supported producers. Coffee was selected because it is the primary focus crop for one of the projects and is the crop with the highest earning potential for clients. The handicrafts value chain is a smaller focus for both of the projects and represents a new source of non-agricultural income with high levels of demand from international buyers.

Findings

The findings of this study reveal opportunities to incorporate nutrition-sensitive agriculture thinking and interventions across the projects as well as within the enabling environments of each commodity value chain. Although the objective of both activities was to increase income for value-chain participants, coffee and green bean producers reported that they had not yet perceived a noticeable increase in household income. Recall and perception might be influenced by their cash flow, as green bean and coffee producers in the participating cooperatives are paid annually, at the end of the harvest, which had occurred a few months before this study took place. For year-round cash flow, producers reported relying on loans from the cooperatives. On the other hand, handicraft producers reported increased earnings and identified an impact on household investments and priorities. The project will be collecting data on income in the endline survey.

During interviews, several opportunities for increasing and strengthening production and processing practices to improve nutrition-sensitive outcomes were mentioned. There is not a standardised set of messages about best agricultural practices, although each cooperative has technicians who are available to provide trainings and support farmers. The technicians noted that, with improved techniques, production on the currently cultivated land could significantly increase. There is no significant incentive for increasing production of green beans, however, as that market is saturated: following the 2013 harvest, producers destroyed a portion of their crop because they did not have buyers who could purchase all of it. Small greenhouses were identified as an opportunity to grow new crops, such as asparagus, for which there is buyer demand. Increases and diversification of production were seen as ways to both increase income and diversify consumption.

The need for technologies that save time and to diversify and increase production and income opportunities were mentioned by both farmers and technicians during interviews. Technologies such as coffee pulpers and dryers that would allow producers to process crops at the cooperative level were noted to ensure consistent quality and avoid waste. A drip irrigation component, introduced in some green bean cooperatives, reaches only a small percentage of producers: 2% in one cooperative and 18% in another.

Processing and storage techniques were also discussed as areas of opportunity as most of the cooperatives do not process products on-site. Green beans are collected by the buyer and sorted at a factory, with the rejected portion destroyed. The few cooperatives that process horticultural products did not participate in this study. Coffee producers complete most of their own drying and pulping at home. In 2013, a percentage of the crop was lost because coffee fermented when a rainy harvest season made it impossible for farmers to dry the beans.

The value chains have few if any links to local markets because they do not pay well enough. Although horticulture cooperative members acknowledged demand for horticulture products, farmers prefer to grow products for buyers who will guarantee prices and pay freight costs. Producers mentioned that they keep some of their crop to consume at home. Additionally, there seems to be interest in the home garden component that both activities promote for home consumption, but many producers lack sufficient land or water to grow everything they consume at home and so prioritise export crops. Availability and access of diverse and nutritious foods locally are limited in some project areas; opportunities for the cooperatives to sell more should be explored.

Members of every cooperative interviewed identified soil erosion and deforestation as some of the greatest challenges for local farmers and communities. Long-term water availability is another concern. Participants from primary buyers mentioned that the main motivation for working with cooperatives located a significant distance from their factory is access to community water sources for irrigation, as community water sources are lacking in many areas close to Guatemala City. None of the cooperatives has a strategy in place to address the challenges of deforestation, lack of water or soil erosion.

Although handicrafts comprise the smallest value chain, the potential for growth is large and a ready market exists. One project is revitalising handicrafts traditions that had nearly disappeared in the Western Highlands. This has resulted in new jobs and an additional source of regular income. Unlike horticulture producers, as handicrafts producers learn to create high-quality products they have become unable to meet demand. One interviewee mentioned that the project hopes to work with handicraft producers to create business plans that include cost structures as activities have not calculated projections for linking improved production capacity, costs and markets. Previously, producers have been forced to incur a loss when selling products because they were unaware of production costs when accepting the work.

Conclusion

More evidence and practical examples are needed to enhance opportunities to make value-chain activities more nutrition-sensitive. Feed the Future projects include a number of value-chain activities that can test assumptions and identify better practices and opportunities for improvement. There is still a lack of clarity about how value-chain activities should be expected to contribute to nutrition outcomes, as well as what projects that work with value chains should measure and how. Instead of funding activities with separate streams for agriculture and nutrition interventions, multi-sectoral work that improves the nutrition sensitivity of any value chain, regardless of the commodity’s nutritional content, should be funded. Good agriculture practices can be nutrition-sensitive in and of themselves and can yield increased production of diverse foods, improved soil and environmental health, increased incomes for male and female producers, and make more time available for caregivers and other household members to spend caring for children.

Although reaching households is important for achieving maternal and child nutrition results, opportunities for linkages to nutrition must be considered thoroughly before they are implemented at (or applied to) the household level. The opportunities described in this report provide possible leverage points for making value chains more nutrition-sensitive. They also facilitate discussion on further developments that will contribute to improved nutrition and agriculture outcomes for Guatemala and other Feed the Future country portfolios.

References

Arlington, VA: USAID/Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING). Available at www.jsi.com/JSIInternet/Inc/Common/_download_pub.cfm?id=14340&lid=3

Herforth, A., and J. Harris (2014). Understanding and Applying Primary Pathways and Principles: Brief 1, Improving Nutrition through Agriculture Technical Brief Series.

Feed the Future (2011). Guatemala: FY2011-2015 Multi-Year Strategy. Washington, DC: Feed the Future. Available at www.feedthefuture.gov/sites/default/files/country/strategies/files/ GuatemalaFeedtheFutureMultiYearStrategy.pdf

UNICEF (2009). Tracking Progress on Child and Maternal Nutrition: A Survival and Development Priority. New York: UNICEF. Available at www.unicef.org/publications/files/Tracking_Progress_on_Child_and_Maternal_Nutrition_EN_110309.pdf

USAID Guatemala (2011). Request for Applications (RFA) Number: RFA-520-11-000003 Rural Value Chains Project. Available at www.grants.gov/web/grants/search-grants.html