Regional conference on responding to challenges of undernutrition in West Africa

By Christelle Huré, Regional Advocacy Adviser, Action contre la Faim West Africa Regional Office

By Christelle Huré, Regional Advocacy Adviser, Action contre la Faim West Africa Regional Office

In June 2015, Action Contre la Faim (ACF), in partnership with the SUN Civil Society Network (SUN CSN) and UNICEF, organised a regional conference in Dakar, Senegal, on How to respond to the remaining challenges of the fight against undernutrition in West Africa. About 100 stakeholders from the region attended the event. The objective was not to develop a roadmap to fight undernutrition in West Africa or to take further commitments, but to reflect collectively on the current situation and identify progress, good practices to be scaled up, challenges ahead and opportunities to be seized.

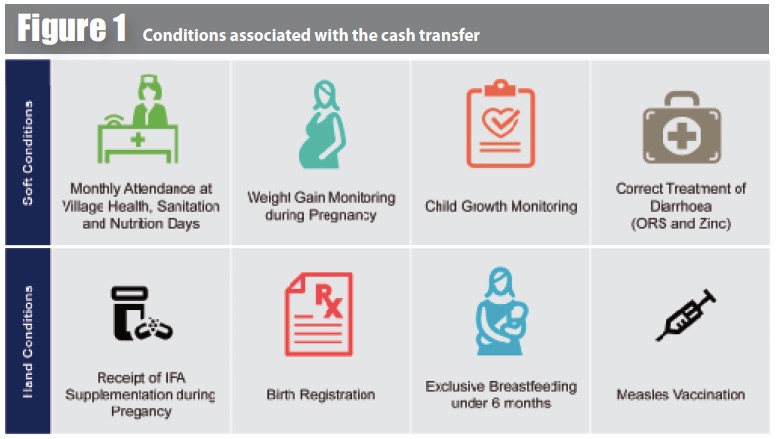

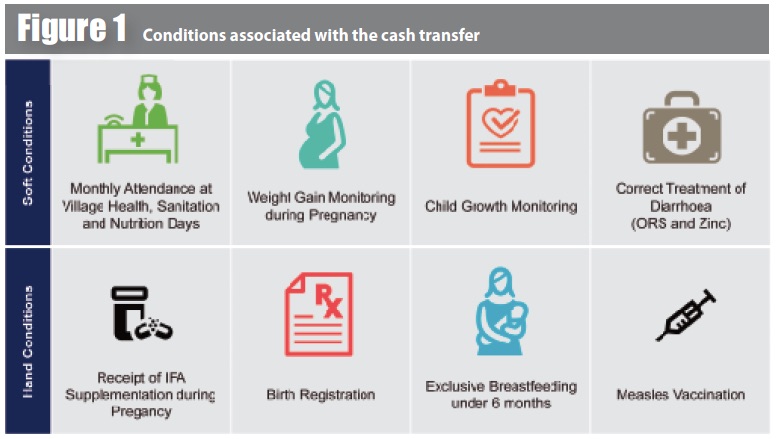

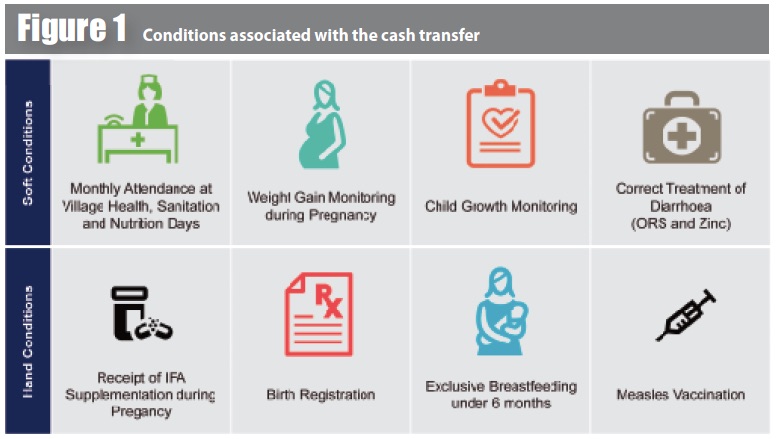

The overview of the nutritional situation in West Africa reveals a mixed picture (For the purpose of this article, the West Africa region is defined as the seven Sahel countries (Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria and Senegal) as well as the coastal countries (Benin, Cape Verde, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Sierra Leone and Togo). On one hand, there has only been slow progress in reducing undernutrition, especially compared with other regions of the world. For instance, stunting rates are not declining (except for a decrease of more than 2% in 2014 in six of the 17 West Africa countries – Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Mali, Mauritania, Senegal). Furthermore, while the prevalence of acute malnutrition is generally decreasing, the caseload keeps increasing (see Figures 1 and 2 for trends in the Sahel). Over the past five years, the number of children under five suffering from severe acute malnutrition (SAM) has increased by 25%. On the other hand, great efforts have been made in terms of scaling up treatment of acute malnutrition, funding has been mobilised, new data are available and states have made political commitments to fight against hunger (Nutrition for Growth Conference, Malabo Declaration, within the SUN Movement).

The best practices and conditions for success are known in West Africa but have not been fully achieved: national leadership, which is essential to effective and efficient coordination; programme quality (effective targeting; thorough analyses of the causes of undernutrition; joint implementation of short-term and long-term interventions; joint implementation of treatment and prevention; involvement of community; monitoring and evaluation); improved financing in quantity and quality (short-term and long-term); responsibility and accountability; improved knowledge; support to civil society and recognition of its role. Overall, the conditions for success show that it is essential to consider the complexity of undernutrition. Undernutrition should be seen not only as a feature of humanitarian emergencies but also as a development and public health priority which requires the sustainable and long-term mobilisation of a diverse range of stakeholders and contributing sectors.

In order to effect these practices and conditions, several initiatives, frameworks and programmes, both at regional (Global Alliance for Resilience (AGIR), Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Zero Hunger Initiative)) and global levels (Renewed Efforts Against Child Hunger and undernutrition (REACH), Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN)), have recently emerged in West Africa. These initiatives pursue the same goal to tackle hunger, face the same challenges, involve the same stakeholders and all seek to highlight the leadership of governments and regional institutions. While efforts have been made towards alignment and coordination, overall communication and consistency between these initiatives remain limited. Coordination and clarification on the harmonisation of these different initiatives under the leadership of regional organisations (ECOWAS and the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU)), is essential for a sustainable and efficient fight against food insecurity and undernutrition. Clear communication channels need to be defined. Beyond consistency, each initiative should strengthen its organisational and technical capacity, work on the monitoring and evaluation of its implementation and impact on the community, and ensure improved inclusion of civil society.

All these initiatives agree on one point: the need for contributing sectors to implement a series of nutrition-sensitive actions complemented with nutrition-specific interventions. Considering the multi-sectoral causes of undernutrition, contributing sectors must mobilise through the integration of nutrition into their respective policies, while nutrition multi-sectoral policies must in turn integrate all sectors and demonstrate their potential and actual impact on nutrition. These policies must then be translated into concrete programmes on the ground, with adequate financial resources.

Despite current consensus on the need for a multi-sectoral approach, implementation in practice is much more complex and still faces many difficulties. An ACF study on the level of inclusion of nutrition in sectoral policies in West Africa (ACF, 2015) reflects these challenges and formulates key recommendations, such as: improve nutrition management tools and enhance nutritional targeting in policies; recognise each sector’s priorities and take into account the implementation capacities of contributing sectors; and invest in the decentralised level, by strengthening coordination and positioning nutrition in local development issues.

The experience of Senegal, which adopted a multi-sectoral approach in the fight against malnutrition a few years ago, shows that the implementation at the highest level of a multi-actor and multi-stakeholder coordination platform (Cellule de Lutte contre la Malnutrition, CLM,) can promote the positioning of nutrition. It also facilitates the tackling of the various drivers of nutrition and the mobilising of funding. The Senegalese experience also shows the essential role that MPs can play, particularly in advocacy for domestic resource mobilisation. A study led by Senegalese MPs on 2013-2015 budget lines allocated to specific nutrition interventions or nutrition-sensitive interventions revealed that many ministries contribute financially to the fight against malnutrition without people knowing it due to lack of information-sharing.

In general, the political and institutional environment in West Africa is increasingly favourable to nutrition. This is due to a stronger institutional anchoring, a policy framework that integrates nutrition, and increased funding. However, there are still challenges ahead, including the needs to:

- Strengthen the institutional anchoring at the highest level to promote the involvement of all line sectors;

- Develop impact measures and strengthen evidence on the effectiveness of multi-sectoral interventions; and

- Strengthen the coordination and implementation of policies at the local level, with strong involvement of the community and with enhancement of the role of civil society.

The integration of nutrition at the programmatic level is also key. Multi-sectoral programming is widely recognised and accepted today; interventions have been identified (water/sanitation/hygiene, agriculture, behaviour change, social protection, etc.) and promoted (especially by UNICEF and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). However, a shift is still needed to move from an opportunistic approach to a systematic and pragmatic approach, ensuring multi-sectorality at all project management phases (planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation). To achieve this:

- Multi-sectoral programmes must be systematically based on knowledge and understanding of local causes of undernutrition (the ACF Link-Nutrition Causal Analysis (NCA) study is one useful approach in this regard);

- Sectors should further improve coordination (same geographical area and same targeting);

- Evidence of the impact of sector interventions on undernutrition must be better shared and used to promote their scale-up. Evidence could be further strengthened through thorough monitoring of the implementation of multi-sectoral programmes and their real impact;

- The ‘Do no harm’ principle should guide action in two ways: the potential negative impacts of each sector on nutrition must be controlled and the potential positive contribution of each sector to nutrition should not prevent it from achieving its sector-specific goals and priorities; and

- Beyond each sector, each stakeholder has a role to play: UN agencies, NGOs and civil society must support countries in designing multi-sectoral programmes on a large scale, based on best practices and lessons learned; and donors and governments must allocate the necessary resources to implement these programmes.

The solutions to fight against undernutrition in West Africa are known and proven, but have yet to be scaled up. One of the obstacles to scale-up remains the mobilisation of financial resources, which must be sufficient, flexible and tailored to the needs of the region, with financing both in emergencies to treat children suffering from acute malnutrition but also long-term to address the underlying causes of both acute and chronic malnutrition.

While governments should mobilise their domestic resources and progressively increase the budget allocated to nutrition, international donors have a key role to play to support them in this effort. The link between relief and development and the financing of the multi-sectoral approach or coordination between donors are challenges that remain. In the West Africa region, emergency and development donors recognise the recurring nature of food and nutrition crises, have invested, and continue to invest heavily in the fight against undernutrition. Besides treating acute malnutrition, which remains essential for saving lives and reducing child mortality, investments are still needed for prevention.

Several good practices and suggested improvements can be highlighted:

- Introduce nutrition indicators in programming documents and in the result frameworks of development projects;

- Increase funding for nutrition-sensitive interventions, with clear nutrition objectives and impact measurement indicators;

- Mobilise flexible and long-term funding that addresses at the same time both the management and prevention of malnutrition; and

- Integrate interventions that can have a strong impact on nutrition in the long term in donor strategies (e.g. climate change and population growth).

For more information, contact: Christelle Huré.

The full report of the conference is available here in French.

References

ACF, June 2015 Integration of nutrition into contributing sector programmes and policies. Synthesis report of a West Africa regional case study. See here.