The nutrition-sensitive potential of agricultural programmes in the context of school feeding: lessons from Haiti

By Nathan Mallonee, Jason Streubel, Manassee Mersilus and Grace Heymsfield

Nathan Mallonee is the Director of Program Effectiveness for Convoy of Hope’s (COH) international programme. He holds an MPP from Georgetown University in International Policy & Development and oversees COH’s programme design and evaluation for nutrition, agriculture, and livelihood projects in Central America, the Caribbean, East Africa and Asia.

Jason Streubel is a Senior Advisor for Agriculture and Science at COH, an associate professor of Applied Science at Evangel University, and an adjunct faculty member at Washington State University, where he earned his PhD in Soil Science: Soil Fertility. He has launched agriculture projects for COH in five countries, including Haiti.

Manassee Mersilus is the lead agronomist for FOME (Fondation Mission de l’Espoire). He has a degree in Plant Science & Agronomy from the National Agriculture University of Haiti and leads a team of four agriculture technicians to train, teach, demonstrate and oversee ongoing projects.

Grace Heymsfield is a Technical Advisor in Nutrition and Child Health for COH. She has previously worked for COH in Haiti as a Monitoring and Evaluation Fellow and is currently studying for her Masters in Public Health at the University of Michigan.

Special acknowledgment should be made to Dr. Hal Collins and Dr. Phillip Miklas of the United States Department of Agriculture’s Agriculture Research Service for supplying the valuable bean lines and providing advice and field assistance.

Location: Haiti

What we know: Haiti suffers from chronically high levels of undernutrition and food insecurity (a third are food insecure), potentiated by the 2010 earthquake.

What this article adds: Since 2010, Convoy of Hope (COH) has implemented a growing school feeding programme, largely to primary schools in Haiti. Nutritious meals were provided with some targeting to malnourished children. A selection of schools received nutrition and hygiene training. To boost the local economy, an agricultural extension programme was designed to boost agricultural production to enable food supply to the feeding programme and increase farmer income. The primary inputs were expert access, educational workshops and local seeds. Growth in yield translated to an average increase in household income from US $2 per day to $7. The intervention is considered a success by the community. Using local church networks was instrumental to buy-in. The programme is being further developed to better evaluate and capture nutrition outcomes at household level and to strengthen nutrition sensitivity.

Context

Haiti is the poorest country in the western hemisphere, with 61.7% of the population living below the international poverty line of US $1.25 per day. Economic and socio-political factors contribute to high rates of food insecurity nationwide. This has led to 23.4% of Haitian children being chronically undernourished (stunted) and 10.6% acutely undernourished (wasted). The 2010 earthquake that left more than 220,000 dead, 300,000 injured and millions displaced prompted immediate action to address food insecurity, as average meals per day fell from 2.48 to 1.58 (Feed the Future, 2011). Though districts nearest to the earthquake have improved food security, approximately a third of the population remains food-insecure (see www.wfp.org/countries/haiti/overview).

Haiti is the poorest country in the western hemisphere, with 61.7% of the population living below the international poverty line of US $1.25 per day. Economic and socio-political factors contribute to high rates of food insecurity nationwide. This has led to 23.4% of Haitian children being chronically undernourished (stunted) and 10.6% acutely undernourished (wasted). The 2010 earthquake that left more than 220,000 dead, 300,000 injured and millions displaced prompted immediate action to address food insecurity, as average meals per day fell from 2.48 to 1.58 (Feed the Future, 2011). Though districts nearest to the earthquake have improved food security, approximately a third of the population remains food-insecure (see www.wfp.org/countries/haiti/overview).

Haiti suffered from high levels of undernourishment and food insecurity prior to the 2010 earthquake. In 2005, one in three children in Haiti suffered from chronic undernutrition. Six in ten children were anaemic. In response, COH initiated a nutritional support programme in schools in 2007 through USAID’s International Food Relief Partnership (IFRP). The project was primarily implemented through COH’s partner Mission of Hope (MOH) and targeted 6,000 children in primary schools with a supplementary meal. In 2010, COH rapidly scaled up its Haiti school feeding programme (SchFP) – which had grown to 13,000 beneficiaries since 2007 – to meet increased needs after the earthquake. As the number of beneficiaries grew, supplemental in-country food purchases were planned to support the local economy and reduce dependence on imported food assistance. Inadequate amounts of food for local purchase led to an intervention to train and equip farmers to increase yields and thus supply the SchFP.

Convoy of Hope (COH) is a faith-based, non-profit organisation founded in 1994 and headquartered in Springfield, Missouri, USA. Since 1994, COH has served more than 70 million people and is often active in emergencies by providing humanitarian assistance, mainly in the sectors of food and nutritional security, to affected populations in the United States, Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, Europe, the Middle East and Asia. COH also has ongoing projects in ten developing countries (El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Haiti, Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, South Africa, and the Philippines) to reduce rates of undernutrition and improve educational outcomes for vulnerable children. In total, nearly 150,000 children from these ten countries are enrolled in the Children’s Feeding Initiative, which provides nutrient-dense meals primarily through schools and community centres. Since 2010, COH has intentionally introduced and scaled interventions that address the underlying causes of childhood undernutrition, including projects in agriculture, women’s empowerment, micro-enterprise, and water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH).

Project overview

The SchFP grew from 13,000 children in 2010 to 60,000 in 2012 and ultimately 85,000 in 2013. Supplementary food was primarily distributed through schools, the vast majority of which were private schools since Haiti lacks a strong public school network (World Bank, 2006). Community members prepared and served hot meals to students each day of the school year. During the 2013 and 2014 school years, 425,000 meals were served weekly. Schools were allocated additional food for take-home rations; children identified as undernourished by school and/or COH staff received the rations.

The SchFP grew from 13,000 children in 2010 to 60,000 in 2012 and ultimately 85,000 in 2013. Supplementary food was primarily distributed through schools, the vast majority of which were private schools since Haiti lacks a strong public school network (World Bank, 2006). Community members prepared and served hot meals to students each day of the school year. During the 2013 and 2014 school years, 425,000 meals were served weekly. Schools were allocated additional food for take-home rations; children identified as undernourished by school and/or COH staff received the rations.

The SchFP targeted children in primary school, though some schools combined primary with pre-primary and secondary schools. While school administrators were encouraged to prioritise meals for younger children, in practice the ages for beneficiaries ranged from two to 25 years. The vast majority (75%) of schools were located in the Ouest department, though COH supported schools in the seven other departments as well.

COH funded the project through private donations of cash and food aid. The programme provided various fortified food mixes, and each serving size aimed to address common nutritional deficiencies in Haiti. The caloric value of one serving was 210 calories; however, staff observed children more often than not received a larger allocation: 1.5 serving sizes on average. Each child received 11g of protein at minimum and up to 100% recommended daily intake of critical vitamins and minerals such as Vitamin A, iron, zinc, and vitamin B12. Through the encouragement and observation of MOH’s supervision staff, it was noted these servings were often supplemented by schools with locally procured fruits and vegetables.

During the first two weeks of each month, distribution trucks with trained warehouse staff were dispatched daily from MOH’s warehouse in Titanyen. At each school, ‘responsibles’ (i.e. principals or administrators) were required to confirm the number of beneficiaries, attendance numbers and programme compliance (planned usage versus actual usage) before receiving the next month’s disbursement of food. A team of supervisors also conducted site visits to ensure the food was being prepared properly and conduct spot checks to confirm attendance and beneficiary numbers.

Starting in 2014, COH supported the provision of hands-on nutrition and hygiene training at a selected sample of schools through the WASH programme led by MOH’s community health nurse. The pilot plan reached approximately 20 schools within or near the Cabaret area. Training sessions were tailored to age group and included topics such as hand-washing, cholera prevention and dental hygiene. COH’s partnership with MOH also created a unique opportunity to provide medical care. Children identified as having special medical needs by supervision staff, often in consultation with teachers or orphanage directors, were referred to MOH’s medical clinic in Titanyen.

Out of a desire to reduce the amount of imported food assistance and help the local economy, a plan was made in 2011 to purchase a portion of the food for the programme from within Haiti. The intention was to buy the food directly from two core communities in the Ouest department where the programme was heavily concentrated (Turpin and Orange); unfortunately, it was determined there were not sufficient quantities of locally grown food. This led to a plan to train and equip groups of small-scale farmers in these communities to build their capacity and increase their yields.

Jason Streubel (COH) and agronomists from MOH designed this agricultural extension programme; the primary objective was to boost agricultural production so that farmers could get increased income and contribute food to the SchFP. From 2012 through 2014, more than 1,600 farmers from Orange and Turpin received classroom and field training, support from a team of Haitian agronomists and provision of improved varieties of locally sourced, open-pollinated seed varieties of black bean, pigeon pea and sorghum seeds. The project was implemented through a network of churches from the communities. Depending on market scenarios, MOH would purchase produce from the project participants at market prices. In addition, all participants were required to donate 10% of their initial harvest to MOH for use in the SchFP. The pigeon peas and black beans were packaged into bags at the MOH warehouse along with rice that was procured on the local market. In 2014, a total of 26.8 million meals were distributed in Haiti for the SchFP. 855,006 of those meals were acquired and packaged locally.

The primary activities for the agricultural extension project were providing small-scale farmers in these isolated, mountainous areas with hitherto unattainable resources: full-time access to a trained Haitian agronomist, monthly educational workshops and dispersion of locally procured seeds. The seed distributions were held in conjunction with the local community leaders who helped ensure fair and equitable distributions. The leaders and local agronomist enrolled 200 beneficiaries in the programme per project cycle, which was coordinated with the growing season. They distributed seeds to each farmer for two or three different crops (maize, sorghum, pigeon pea, or black bean) based on the individual’s need and appropriate growing seasons. Each individual signed a contract at the beginning of the cycle, agreeing to save 10% of his or her harvest as seed for subsequent seasons and to donate 10% of the initial harvest back to the SchFP.

The primary activities for the agricultural extension project were providing small-scale farmers in these isolated, mountainous areas with hitherto unattainable resources: full-time access to a trained Haitian agronomist, monthly educational workshops and dispersion of locally procured seeds. The seed distributions were held in conjunction with the local community leaders who helped ensure fair and equitable distributions. The leaders and local agronomist enrolled 200 beneficiaries in the programme per project cycle, which was coordinated with the growing season. They distributed seeds to each farmer for two or three different crops (maize, sorghum, pigeon pea, or black bean) based on the individual’s need and appropriate growing seasons. Each individual signed a contract at the beginning of the cycle, agreeing to save 10% of his or her harvest as seed for subsequent seasons and to donate 10% of the initial harvest back to the SchFP.

Group training sessions, taught by the local agronomists, were held once a month. The monthly training sessions were not limited to that project cycle’s beneficiaries; each training session was open to anyone from the community, including previous participants. Topics at the training sessions included soil fertility, integrated pest management, seed saving, irrigation, farm management, composting, and disease and pest identification.

Direct assistance was also provided in the farmers’ fields. Local agronomists made in-person and in-field visits with beneficiaries on a regular basis. The agronomist lived in the farmers’ community and was regularly in the fields throughout the week. During these visits, the agronomists directly applied lessons from the monthly training sessions to the farmer’s situation. In addition, the agronomist could assist in helping anticipate future issues or address questions or concerns the farmer may have. In certain cases, issues or questions that could not be answered in the field were brought back to COH’s agriculture experts for assistance.

Experiences

During the time of this study, from 2012 to 2014, the results of the SchFP were limited to monitoring data, including monthly activity and distribution reports. COH was not able to collect reliable anthropometric data of children in the programme prior to 2015, though COH’s program effectiveness unit has been working over the past year to build MOH’s capacity to improve data quality and evaluation methodology. As part of this process, COH instituted a more robust monitoring and evaluation plan for the SchFP that included anthropometric measurements on a statistically significant number of beneficiaries at a set of representative, randomly selected schools.

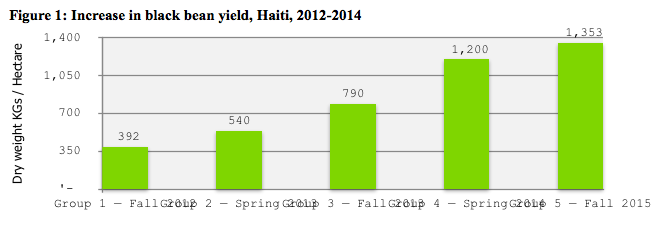

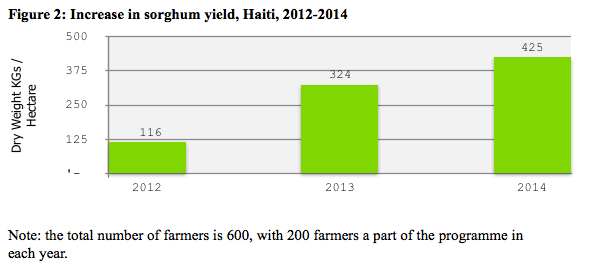

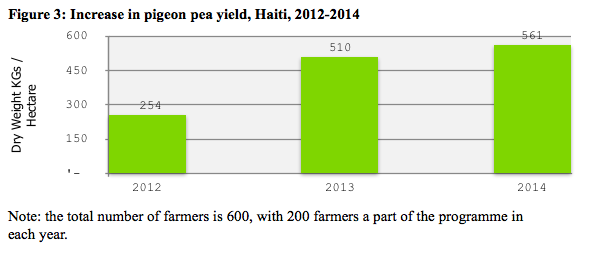

To determine changes in yields and household income, pre- and post-season surveys were implemented. From 2012 to 2014, during five seasons of black bean harvest, project beneficiaries (n=1,000) experienced a 245% increase in black bean yield – from 392 kg/ha in 2012 to 1,353 kg/ha in 2014. Similar increases were seen with sorghum (266%) and pigeon pea (121%). This translated to an average increase in household income from US $2 per day to $7, and the increased yield was achieved without the addition of any commercial fertilisers.

The pre-season surveys also indicated how most families lacked the capacity to save seed from their harvests for the next growing season; the entire harvest was consumed or sold for the household’s survival. As the yields increased, the agronomists noted how the habits of the community were changing; more families were consistently saving seed. Finally, although quantitative soil data were not collected, qualitative data were collected through interviews and on-site soil texture tests by staff. These observations showed improved soil productivity and fertility, an increase in organic matter and an increase in water holding capacity.

COH agronomists collected the yield data for each participant in the programme. Yields were recorded by first-person observation of each harvest collected in cans prior to long-term storage or market delivery. The traditional weight and measurement in Haiti is the basic unit of a ‘can’. A standard can of coffee holds 48 ounces, which represents 5.5 pounds of the harvested product. This measure of volume has been standardised among farmers and has proven to be fairly accurate. The traditional can measurement is converted to kg and kg per hectare. The average land size per participant was 0.4 hectares. This figure was calculated based on baseline interviews and was confirmed during visits by COH agronomists. Figures 1, 2, and 3 show the increase in yield for black bean, sorghum, and pigeon pea respectively. Each time period represents a separate group of 200 participants. The yield recorded is the amount of yield at the end of the first growing season after receiving the education workshops and the seed distribution. The continued increase during each growing season shows in part the cumulative effect of working in the same communities over multiple growing seasons and the increased effectiveness of the project.

Outside of measuring change in yields and income, the ultimate indicator for success of this project was the local perception of success. Community leaders approached COH in early 2015 and suggested that the agriculture project move on to other communities, since they believed their communities were achieving sufficient yields and other communities should also benefit from the project. The leaders said the farmers in the community had now entirely adopted the new methodologies. The impact of the project can be clearly seen in these communities. Land that was once barren is now entirely green. Where bean mosaic viruses once ravaged the bean fields, hardly any evidence of the disease remains. The crops residues are no longer burned and wasted but rather composted or integrated into the soils through livestock.

Outside of measuring change in yields and income, the ultimate indicator for success of this project was the local perception of success. Community leaders approached COH in early 2015 and suggested that the agriculture project move on to other communities, since they believed their communities were achieving sufficient yields and other communities should also benefit from the project. The leaders said the farmers in the community had now entirely adopted the new methodologies. The impact of the project can be clearly seen in these communities. Land that was once barren is now entirely green. Where bean mosaic viruses once ravaged the bean fields, hardly any evidence of the disease remains. The crops residues are no longer burned and wasted but rather composted or integrated into the soils through livestock.

While the main project objective was to boost agricultural production and local contribution to the SchFP, our staff recorded anecdotal information about the impact the project had on the beneficiaries’ households. On a field visit in 2014 one woman said, “My family is healthy, my kids are going to school, I am growing crops for myself and market, and now my son says he wants to be an agronomist.”

The success of this project can be attributed to four main factors. First, it was important to establish a contract with each beneficiary prior to their enrolment in the project that included the required donations back to the SchFP. While these communities knew the benefits of the COH SchFP, some farmers were hesitant to offer 10% of the initial harvests and thus the local agronomists and staff sometimes had to refer to the contracts. This contribution played a large part in reducing dependence on imported food assistance; it also increased local ownership of the SchFP. Participants told COH staff during field visits that “they were now a part of the solution in Haiti”, and in several instances farmers who were no longer participants in the project have continued to donate portions of their harvest to the SchFP.

Second, implementing the training sessions through local church networks increased the trust levels of local farmers. MOH has a history of partnership with local churches and pastors in the Turpin and Orange communities and the local pastors were respected community members. Furthermore, the pastors had a deep knowledge of the communities and could help COH target the most vulnerable farmers.

Third, COH conducted a series of field trials on different black bean varieties to determine which produced the highest yields in these particular communities. In April 2013, 20 different bean lines were tested using a randomised block design with four treatment groups and three replications. The experiment included a corn rotation and the integration of local pigeon pea and bean varieties as the control. In all varieties except DPC 40, the salinity of the soil at the experimental site limited all growth and most germination. In a follow-up experiment, a plot of land in the mountain communities was used to replicate the larger experiment with ten lines and three replicates. Once again, the DPC 40 experimental variety was the best performer in the Haitian environment. Given its performance, and since this variety was already being researched by a Haitian university (Faculté d’Agronomie et de Médecine Vétérinaire), the DPC 40 variety was selected for further distribution in the communities. The remaining data from the field trials were sent to the participating breeders to continue to work on new varieties, some of which are more salt-tolerant.

Finally, COH’s commitment to working in these two communities for multiple years led to increasing yields for each new group of farmers. The cumulative effects of the local farmers’ knowledge are likely part of the reason each subsequent group of farmers achieved higher yields than the previous group. Also, the open training sessions for any community member, including past or future participants, provided a level of ongoing extension and consultative services. By being inclusive instead of exclusive, everyone in the community was able to benefit from the project. It also created a deeper sense of shared understanding on improved farming techniques.

Finally, COH’s commitment to working in these two communities for multiple years led to increasing yields for each new group of farmers. The cumulative effects of the local farmers’ knowledge are likely part of the reason each subsequent group of farmers achieved higher yields than the previous group. Also, the open training sessions for any community member, including past or future participants, provided a level of ongoing extension and consultative services. By being inclusive instead of exclusive, everyone in the community was able to benefit from the project. It also created a deeper sense of shared understanding on improved farming techniques.

Several lessons were learned through particular implementation challenges. Primarily, it is important to focus first on improving the quality of soil prior to any seed distributions. Also, growing rice in this particular region of Haiti is challenging due to lack of consistent water, thus the distribution of seeds for rice was discontinued after the first project cycle. Finally, the project faced initial issues with adoption of new techniques. Farmers in most communities need to see the profitability of the methods being taught before 100% adoption is realised. While working through local churches is believed to have reduced the reluctance, it was still apparent during the first several growing seasons of the project.

Discussion

COH’s agriculture project contributed to a large and rapidly growing SchFP. It is likely that the full impact of this project on the nutritional outcomes of the children in the households of the participants was not fully recognised through the project monitoring. What is clear, however, is that a successful agriculture training project can directly contribute to SchFPs while also improving the livelihoods for the farmers and their households.

As COH continues to refine its programmatic strategy in Haiti, one point of focus will be to ensure the agriculture extension projects are more nutrition-sensitive. This will start by better capturing and evaluating the effects of the current projects on household-level nutritional outcomes. In addition, the project activities are being re-evaluated to determine areas where nutritional outcomes of children can be improved. For instance, local agronomists can more directly assist local schools in developing school or community gardens for fruits and vegetables that provide extra micronutrients and flavour to the school meals. Similarly, COH could include training sessions on how to develop household gardens that could enhance access to diverse diets. These gardens would be in addition to planting fields with the more traditional ‘cash crops’ of maize, sorghum, black bean and pigeon pea. Another interesting aspect is that 48% of the agriculture participants were women; this provides COH with the ability to directly reach mothers with nutrition and hygiene education during the in-classroom or in-field agriculture training sessions. This would require local agronomists to be cross-trained in nutrition and hygiene, but it could be a cost-effective measure for reducing stunting by improving the nutrition of children in the first 1,000 days.

The agriculture project is now being replicated in communities outside Turpin and Orange; the intent is to scale up the agriculture project to more communities so that the SchFP is supplied with an increasing amount of locally procured food and vulnerable households and communities can achieve food security.

For more information, email Nathan Mallonee

References

Feed the Future (2011). FY 2011-2015 Multi-year strategy. Retrieved from www.feedthefuture.gov

World Bank (2006). Haiti - Social resilience and state fragility in Haiti: a country social analysis. Washington, DC: World Bank. Retrieved from www.documents.worldbank.org