Is reliable water access the solution to undernutrition?

Summary of research1

Location: Global

What we know: Irrigation interventions have the potential to reduce undernutrition by impacting food security, nutrition and health.

What this article adds: A recent systematic review identified multiple pathways of irrigation impact on the underlying causes of malnutrition. There is evidence (largely from Africa) of positive impact on food security, including increased productivity and availability of food, improved dietary quality, and increased income (via cash crops). Negative impacts include monocropping. More rigorous evaluations of the impact of irrigation interventions on nutrition outcomes are needed; evidence is lacking. Recommendations are made on how to make irrigation interventions more nutrition-sensitive.

Interventions aimed at increasing water availability for livelihood and domestic activities have great potential to counter various determinants of undernutrition, by improving, for example, the quantity and diversity of foods consumed within the household, income generation and women’s empowerment. However, current documented evidence on the topic is spread across many different publications. This paper aims to connect the dots by reviewing the literature available on the linkages between irrigation and food security, improved nutrition, and health.

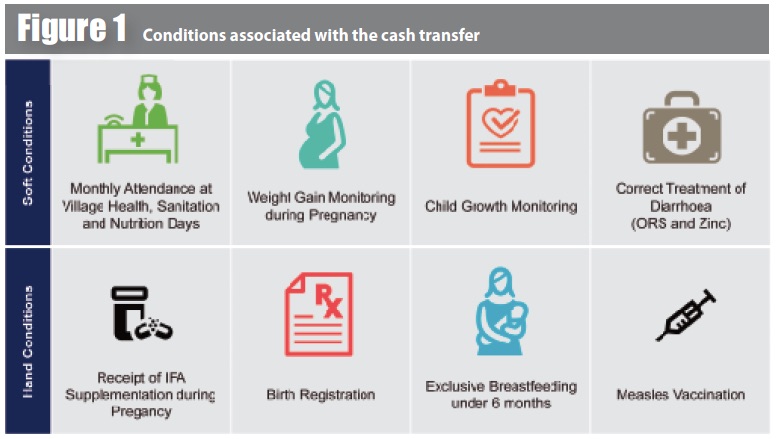

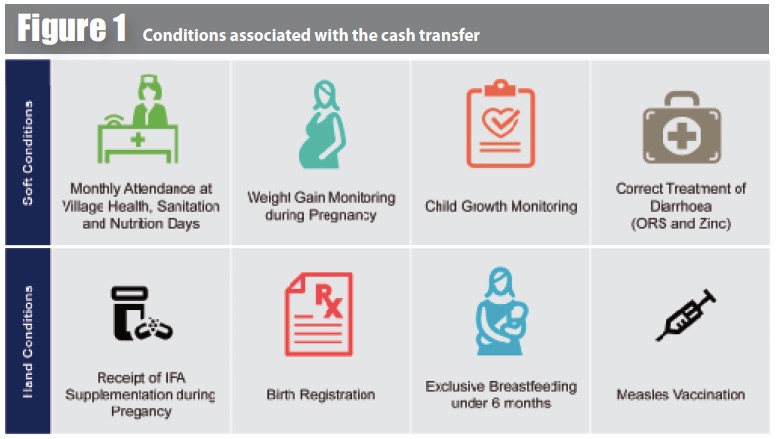

The review begins with an exploration of the main pathways involved, displayed in Figure 1. Irrigation can improve dietary diversity (through increased agricultural productivity and crop diversification); provide a source of income (from market sales via increased production and employment generation, particularly during dry seasons where labour requirements are low); provide a source of water supply and improve sanitation and hygiene; and provide an entry point to strengthen women’s empowerment (through increased asset ownership and increased control over resources). To test the impacts of irrigation on nutrition, health and gender outcomes through these pathways, the author conducted a literature review on the available evidence. Gender variables are given special consideration because women’s roles in agriculture and within the household are considered a critical determinant of nutrition and health outcomes.

A systematic key word search of peer-reviewed papers and grey literature yielded 27 papers for review. Almost all of the included studies focused on countries in Subsub-Saharan Africa, except for five that studied Asian cases. Dams and canal irrigation were the main type of irrigation evaluated in 12 studies, while small-scale private irrigation was evaluated in eight studies. Micro-irrigation technologies were the main focus of five studies, home gardens of four studies, and irrigation with wastewater was the focus of one study. Information on the main features of the irrigation system was missing from two studies.

Findings show that there is evidence that irrigation interventions can positively impact underlying causes of malnutrition through multiple pathways, including increased productivity and availability of food supplies and improved diets (in quantity and quality). For example, a study in Ethiopia documented that farmers using irrigation systems produced crops twice and sometimes even three times per year, compared to a single cropping season with rain-fed agriculture (Aseyehegn, Yirga & Rajanet al, 2012). Several of the studies showed that irrigation can lead to increased production of cash crops, providing additional income to the household and greater potential for the purchasing of nutritious food. Many studies also showed that irrigation can boost fruit and vegetable production, which can increase household consumption and may also be sold for additional income. This can, in turn, lead to increased food availability in the community and increased household purchasing power. There is also evidence of a positive effect on food security. For example, one study in Malawi documented that 70% of households stated that they were food insecure (defined by not having enough food to last until the next harvest) but that after the adoption of an irrigation scheme, only 9% of households reported experiencing food insecurity (Mangisoni, 2008). Other studies, however, showed mixed or inconclusive results, whilest some showed that irrigation can lead to monomonocropping and therefore have potentially negative consequences on underlying causes of malnutrition. Some studies showed that irrigation can increase livestock productivity (through increased water for livestock drinking, bathing and livestock feed availability), although others found no significant impact.

While there is evidence of the effect of irrigation on agricultural production and increased food supplies, the pathways linking nutritional and health gains with irrigation remain understudied. Findings on this relationship were inconclusive. The author attributes this in part to the fact that few studies include comprehensive measures of anthropometry, morbidity, and clinical indicators. Many of the studies included in the review had methodological weaknesses. In some cases, sample sizes were too small to provide conclusive evidence. Self-selection bias and lack of comparable controls were also limitations in several studies. However, it may be difficult to avoid self-selection bias in irrigation studies because randomisation of the beneficiary households is often not feasible in irrigation interventions. Some studies tried to solve the problem with the use of propensity score matching methods. Finally, most studies did not collect panel (longitudinal) data and therefore were unable to control for unobservable effects.

While there is evidence of the effect of irrigation on agricultural production and increased food supplies, the pathways linking nutritional and health gains with irrigation remain understudied. Findings on this relationship were inconclusive. The author attributes this in part to the fact that few studies include comprehensive measures of anthropometry, morbidity, and clinical indicators. Many of the studies included in the review had methodological weaknesses. In some cases, sample sizes were too small to provide conclusive evidence. Self-selection bias and lack of comparable controls were also limitations in several studies. However, it may be difficult to avoid self-selection bias in irrigation studies because randomisation of the beneficiary households is often not feasible in irrigation interventions. Some studies tried to solve the problem with the use of propensity score matching methods. Finally, most studies did not collect panel (longitudinal) data and therefore were unable to control for unobservable effects.

The author concludes that more rigorous evaluations of the impact of irrigation interventions on nutrition outcomes are needed. Developing evidence will be important for the successful implementation of future irrigation projects, especially in Africa south of the Sahara, where the potential to expand irrigation is large and where recent projections indicate that childhood undernutrition prevalence will continue to rise over the next two decades. The author makes six recommendations for designing more nutrition-sensitive irrigation interventions: (1) food security and nutrition gains should be stated goals of irrigation programmes; (2) training programmes and awareness campaigns should accompany irrigation interventions to promote nutrient-dense food production and consumption as well as minimisation of health risks; (3) multiple uses of irrigation water should be recognised in order to improve access to water supply and sanitation, and livestock and aquatic production; (4) women’s empowerment and women’s participation in irrigation programmes should be promoted; (5) homestead food production should be encouraged; and (6) policy synergies between different sectors (agriculture, nutrition, health, water supply and sanitation, education) should be sought.

Footnotes

1 Domènech, L., (2015). Is reliable water access the solution to undernutrition? A review of the potential of irrigation to solve nutrition and gender gaps in Africa south of the Sahara. IFPRI Discussion Paper 1428. Washington, D.C.: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). http://ebrary.ifpri.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15738coll2/id/129090

References

Aseyehegn, K., C. Yirga, and S. Rajan. (2012). Effect of Small-Scale Irrigation on the Income of Rural Farm Households: The Case of Laelay Maichew District, Central Tigray, Ethiopia. Journal of Agricultural Sciences 7 (1): 43–57.

Mangisoni, B. (2008). Impact of Treadle Pump Irrigation Technology on Smallholder Poverty and Food Security in Malawi: A Case Study of Blantyre and Mchinji Districts. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 6 (4): 248–266.

Ruel, M. T., and H. Alderman. (2013). Nutrition-Sensitive Interventions and Programmes: How Can They Help to Accelerate Progress in Improving Maternal and Child Nutrition? Lancet 382 (9891): 536–551.