Impact of agronomy and livestock interventions on women’s and children’s dietary diversity in Mali

By Damouko Bonde

Damouko Bonde is a specialist in project monitoring and evaluation with AVSF Mali.

This project was implemented and supported by Agronomists and Veterinarians Without Borders (Agronomes et Vétérinaires Sans Frontières (AVSF)), the Initiatives Advice Development (Initiatives Conseils et Développement (ICD)) and the European Union.

The ENN extend thanks to Translators without Borders for translating this article from French to English, with special mention of Dona Petkova and George May. The authors also extend thanks to ICD Mali in this regard.

Location: Mali

What we know: Acute malnutrition is prevalent in the agriculturally dependent population of the Mopti region, Mali, despite surplus grain production.

What this article adds: Between 2011 and 2015, AVSF implemented an agronomy and livestock programme to improve dietary diversity of women and children under five in 2,000 vulnerable households. Household dietary diversity scores improved in both the post-harvest and the lean period. During the lean season, the dietary diversity score rose in children aged between 24 and 59 months from 3.9 to 4.4. The proportion of mothers with a low food diversity score fell significantly from 46% to 26% ( p<0.05). Maternal dietary diversity was greater than their young children (aged between six and 24 months); complementary feeding knowledge requires further strengthening. Provision of goats is recommended with support for animal feed and health (particularly brucellosis in a milk-drinking population).

The original article was submitted in French. A French version is available online here.

Background

Mali is a landlocked country with large fluctuations in rainfall. This makes food security a prerequisite for development. The programme described in this article took place in the Mopti region of the Cercles of Bankass and Koro, Mali between July 2011 and May 2015. The majority (78%) of the population of the Cercles practice agriculture but malnutrition remains prevalent and a severe problem. According to Dr Dembélé (Head of the Health Division of the Mopti Regional Health Directorate, Mopti Regional Forum on Nutrition, March 2010): “Malnutrition is a leading cause of morbidity and infant mortality in Mali in general and in Mopti figures from the Demographic and Health Survey in 2006 show that the moderate acute malnutrition rate is 12.7% and severe acute malnutrition prevalence is 5.9%.” The Mopti Regional Forum on Nutrition in March 2010 identified the priority issues in the region for dealing with nutrition as: (1) the availability of food and care for all groups; (2) access to drinking water; (3) diversification of agricultural production; (4) intensifying advocacy and the activities of the IEC/BCC (Information, Education and Communication/Behaviour Change Communication); and (5) ensuring strong management of nutritional activities.

Mali is a landlocked country with large fluctuations in rainfall. This makes food security a prerequisite for development. The programme described in this article took place in the Mopti region of the Cercles of Bankass and Koro, Mali between July 2011 and May 2015. The majority (78%) of the population of the Cercles practice agriculture but malnutrition remains prevalent and a severe problem. According to Dr Dembélé (Head of the Health Division of the Mopti Regional Health Directorate, Mopti Regional Forum on Nutrition, March 2010): “Malnutrition is a leading cause of morbidity and infant mortality in Mali in general and in Mopti figures from the Demographic and Health Survey in 2006 show that the moderate acute malnutrition rate is 12.7% and severe acute malnutrition prevalence is 5.9%.” The Mopti Regional Forum on Nutrition in March 2010 identified the priority issues in the region for dealing with nutrition as: (1) the availability of food and care for all groups; (2) access to drinking water; (3) diversification of agricultural production; (4) intensifying advocacy and the activities of the IEC/BCC (Information, Education and Communication/Behaviour Change Communication); and (5) ensuring strong management of nutritional activities.

The Cercles of Bankass and Koro are characterised by a surplus of grain production. (According to the 2009 agricultural census, in the Cercle of Bankass, 624 kg of cereals are produced per inhabitant, while the need is 250 kg (FAO standards). For Koro, the rate of production is 437 kg per inhabitant.) However, there are food accessibility issues (quantity, quality and price) due to strong exports of products during the first three months following the harvest. A study by AVSF in March 2011 found that three months after the harvest, 50% of the population of the area were already vulnerable to food insecurity and that 4% were already in a food-insecure situation. In addition, diarrhoea frequency among children aged between six and 59 months was high (64%) and can be attributed to poor hygiene. There was also very low food diversity (50% of children had an insufficiently varied diet). Agricultural produce is often sold at low prices to satisfy immediate basic needs and cereals are often the only source of income.

Overview of the project and its objectives

The overall objective and priority of the programme was to improve the diets of children aged between nought and two years and women of childbearing age. This was to be achieved by developing plant and animal production, reducing the drudgery of women’s chores, a range of training (e.g. nutrition, hygiene, horticultural practices and cheese production), and improving food quality in 40 villages in the Cercles of Koro and Bankass. The intervention targeted households vulnerable to food insecurity. These households received support for small-scale livestock breeding. One thousand vulnerable households with at least two children under five have received two goats. An additional 1,000 vulnerable households with one child under five received ten hens plus a breed-improving rooster and improved seeds. The recipients were trained to look after small ruminants and to breed poultry.

The overall objective and priority of the programme was to improve the diets of children aged between nought and two years and women of childbearing age. This was to be achieved by developing plant and animal production, reducing the drudgery of women’s chores, a range of training (e.g. nutrition, hygiene, horticultural practices and cheese production), and improving food quality in 40 villages in the Cercles of Koro and Bankass. The intervention targeted households vulnerable to food insecurity. These households received support for small-scale livestock breeding. One thousand vulnerable households with at least two children under five have received two goats. An additional 1,000 vulnerable households with one child under five received ten hens plus a breed-improving rooster and improved seeds. The recipients were trained to look after small ruminants and to breed poultry.

Training and education sessions on nutrition and hygiene were organised for the benefit of people in the area covered by the project. Radio programmes on nutrition were broadcast on local FM radio stations. Similarly, cookery demonstration sessions using recipes based on local products were performed for the local populations. Awareness-raising sessions discussed how gender and nutrition were interrelated. Mass screening for malnutrition is regularly carried out by traditional birth attendants (TBAs) and community health agents. Malnourished children who were detected were referred to the nearest health centre for attention. Community health agents and TBAs demonstrated hand-washing using soap to encourage good hygiene practices. In order to reduce waterborne diseases, dilapidated large-diameter wells were restored at all the project intervention sites. The project also initiated training on the drying and storage of horticultural products and the manufacture of dry cheese; the latter to deal with the surplus of fresh milk in periods of abundance, thereby making dairy products available year-round.

Results

Dietary diversity scores were measured by AVSF with the assistance of the European Development Fund’s National Authorising Officer and the EU delegation. Results suggest that the package of activities contributed positively to improving food access for households in the implementation area. The proportion of households with acceptable food consumption increased from 67% to 85% during the lean period, largely exceeding the forecasted 75%. In the post-harvest period, the percentage of households with acceptable food consumption rose from 81% to 89%, close to the target of around 90%.

Dietary diversity scores were measured by AVSF with the assistance of the European Development Fund’s National Authorising Officer and the EU delegation. Results suggest that the package of activities contributed positively to improving food access for households in the implementation area. The proportion of households with acceptable food consumption increased from 67% to 85% during the lean period, largely exceeding the forecasted 75%. In the post-harvest period, the percentage of households with acceptable food consumption rose from 81% to 89%, close to the target of around 90%.

For individual dietary diversity (children aged between six and 23 months, children aged between two and 59 months, and mothers with children), the lowest recorded acceptable rate of 50% was registered during the lean period for mothers and for children aged between 24 and 59 months. During the lean season, for children aged between 24 and 59 months, the dietary diversity score rose from 3.9 food groups out of nine to 4.4 groups by the end of the project. During the same period, for infants aged six to 23 months the average dietary diversity score increased from 2.3 to three food groups out of seven at the end of the project.

FAO methodology was used to analyse the dietary diversity of women with children under five and children aged 24 to 59 months. The WHO methodology was used to analyse the dietary diversity of children aged six to 23 months. This explains the difference in the number of food groups included in the calculation of the individual dietary diversity score bracket according to the child’s age.

FAO methodology was used to analyse the dietary diversity of women with children under five and children aged 24 to 59 months. The WHO methodology was used to analyse the dietary diversity of children aged six to 23 months. This explains the difference in the number of food groups included in the calculation of the individual dietary diversity score bracket according to the child’s age.

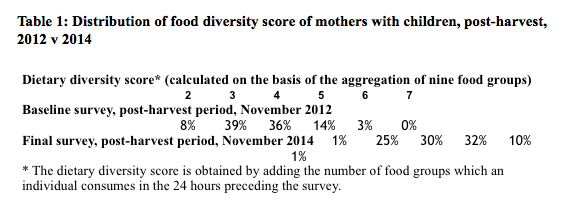

The percentage of mothers with a low food diversity score (≤3 food groups) decreased between the post-harvest baseline (46%) and the final post-harvest survey (26%); this decrease being significant (p <0.05). Almost twice as many mothers had a high food diversity score (≥ 5 groups) in the final post-harvest period (44%) than in the baseline (18%).

Challenges and lessons learned

Challenges and lessons learned

Mothers consumed more food groups than children aged between six and 23 months, with the exception of milk (29% of children consumed it compared with 20% of mothers). These findings highlight a significant need for strengthening the food knowledge of mothers concerning the feeding of young children. There is also a problem regarding the limited amount of time available for mothers to prepare children’s meals.

Small-scale breeding and providing agricultural equipment had a significant impact (p <0.05) on the dietary diversity scores of mothers. The mean dietary diversity score of mothers who had benefited from small-scale breeding was 4.4 out of nine food groups compared with 4.0 for groups for mothers who had not benefited. The dietary diversity score of mothers who had benefited from the provision of agricultural equipment was 4.6 food groups out of nine compared with 4.2 for mothers who had not benefited from this support.

Small-scale breeding and providing agricultural equipment had a significant impact (p <0.05) on the dietary diversity scores of mothers. The mean dietary diversity score of mothers who had benefited from small-scale breeding was 4.4 out of nine food groups compared with 4.0 for groups for mothers who had not benefited. The dietary diversity score of mothers who had benefited from the provision of agricultural equipment was 4.6 food groups out of nine compared with 4.2 for mothers who had not benefited from this support.

The monetary income generated by small-scale breeding facilitated greater access to certain foods. Similarly, providing farming equipment allowed each family to diversify its agricultural production.

We recommend that scaled-up programming should be initiated by providing dairy goats. However, animal feed during the lean period will need to be introduced into the programme. It will also be important to test for brucellosis to ensure that the additional fresh milk consumption is safe. Work is needed to strengthen the knowledge of mothers with children and women of childbearing age concerning diets for young children. This can be achieved by promoting various recipes with high nutritional values based on local products.

For more information, contact Marc Chapon, AVSF National Coordinator in Mali or phone (00223)76368739

Read a French version of this article here.