Severe acute malnutrition: an unfinished agenda in East Asia and the Pacific

By Cecilia De Bustos, Cécile Basquin and Christiane Rudert

Cecilia De Bustos is a nutrition and public health specialist who currently works as an independent consultant. She has more than seven years of experience working in developing countries, mainly in Latin America and Asia.

Cécile Basquin is currently a nutrition in emergencies consultant working with UNICEF in the East Asia and Pacific regional office. She previously held a technical advisory role at ACF New York HQ. She has experience of a wide range of nutrition interventions in sub-Saharan Africa (DR Congo, Nigeria, Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan) and Asia (Pakistan).

Christiane Rudert is Regional Nutrition Advisor, UNICEF East Asia-Pacific Regional Office in Bangkok, providing technical and strategic support on nutrition to 14 countries. With 20 years of professional experience in international public health and nutrition in humanitarian and development contexts, she has worked in Namibia, Zambia, Ethiopia and Mozambique.

The authors acknowledge the immense contribution of the speakers of the Regional Consultation on Prevention and Treatment of Severe Acute Malnutrition in Asia and the Pacific, who provided the information that is the basis for this article (by alphabetical order): Hedwig Deconinck (Public Health Researcher, University of Louvain), Katrin Engelhardt (Regional Nutrition Advisor, WHO WPRO), Alison Fleet (Technical Specialist, UNICEF Supply Division), Aashima Garg (Nutrition Specialist, UNICEF Philippines), Katrien Ghoos (Regional Nutrition Advisor, WFP Asia Regional Bureau), Saul Guerrero (Director of Operations, Action Against Hunger UK), Nam Phuong Huynh (Senior Government Officer, National Institute Nutrition, Vietnam), Jan Komrska (Contracts Specialist, UNICEF Supply Division), Arnaud Laillou (Nutrition Specialist, UNICEF Cambodia), Roger Mathisen (Regional Technical Specialist, Alive & Thrive/FHI 360), Zita Weise Prinzo (Technical Officer, WHO HQ), Dolores Rio (Nutrition Specialist, UNICEF HQ), Christiane Rudert (Regional Nutrition Advisor, UNICEF EAPRO) and Frank Wieringa (Senior Researcher, IRD).

Location: East Asia and the Pacific

What we know: The burden of severe wasting is high in emergency-prone and highly inequitable East Asia and the Pacific but access to treatment is low (indirect coverage estimated at 2%). Low awareness and commitment by government and stakeholders are identified barriers.

What this article adds: In most East Asia and the Pacific countries, Integrated Management of Acute Malnutrition (IMAM) is mainly implemented as a short-term emergency intervention in the region; it has not been a priority among most governments or development partners. While country SAM guidance exists in most countries, the majority are outdated/not endorsed by government. In June 2015, UNICEF and partners led an action-oriented regional consultation on SAM treatment to identify and address constraints and map a way forward. It found there has been progress in Timor Leste, Cambodia, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) and Vietnam in scale-up of pilot interventions, with plans in Myanmar and the Philippines. It addressed the considerable challenges to implementation, including lack of integration in health services, varied system capacity, bottlenecks in supply management, and lack of government investment, with heavy dependence on external financing. There are poor linkages between SAM and MAM management programmes. A context-specific approach to IMAM services delivery, using a health-systems strengthening lens, is needed for each country. Governments should consider IMAM in regional and national nutrition plans, linking acute malnutrition and stunting agendas and emphasising prevention; articulation of programming strategies and adaptation to development, fragile and emergency contexts is needed. Country-specific priorities, accompanied by key actions, must include improved quality and coverage of inpatient and outpatient SAM management services; scale-up in both humanitarian and development contexts; investment in health-system strengthening; health staff training; establishing a nutrition supply chain system; and consistent, targeted regional advocacy on right to treatment. Despite encouragement, as of 2015 only one country has committed financing to IMAM in the short term.

Background

Globally, it is estimated that 50 million children under five are wasted, with approximately two thirds of them living in Asia (UNICEF, WHO & World Bank, 2015). Despite the positive economic growth and great achievements in health and nutrition indicators over the last years, it is estimated that in 2015 almost six million children became severely wasted in East Asia and the Pacific. Moreover, only around 2% of the estimated annual caseload of severely wasted children had access to treatment (according to information originating from the nine countries from East Asia and the Pacific with treatment programmes that reported in 2014). If left untreated, severe acute malnutrition (SAM) in early childhood carries an 11.6-fold increased risk of dying or higher likelihood of contracting infectious diseases (Olofin, McDonald, Ezzati et al, 2013). Moreover, wasted children are more likely to become stunted and develop chronic diseases later in life. Recent trends have shown a high burden of wasting in a number of upper middle-income countries that have no treatment programmes, such as China and Thailand, with close to two million and 250,000 estimated wasted children, respectively.

Globally, it is estimated that 50 million children under five are wasted, with approximately two thirds of them living in Asia (UNICEF, WHO & World Bank, 2015). Despite the positive economic growth and great achievements in health and nutrition indicators over the last years, it is estimated that in 2015 almost six million children became severely wasted in East Asia and the Pacific. Moreover, only around 2% of the estimated annual caseload of severely wasted children had access to treatment (according to information originating from the nine countries from East Asia and the Pacific with treatment programmes that reported in 2014). If left untreated, severe acute malnutrition (SAM) in early childhood carries an 11.6-fold increased risk of dying or higher likelihood of contracting infectious diseases (Olofin, McDonald, Ezzati et al, 2013). Moreover, wasted children are more likely to become stunted and develop chronic diseases later in life. Recent trends have shown a high burden of wasting in a number of upper middle-income countries that have no treatment programmes, such as China and Thailand, with close to two million and 250,000 estimated wasted children, respectively.

In spite of the increased political commitment and the strong momentum for nutrition at the global level, SAM constitutes a largely unfinished agenda: a hidden anomaly in a rapidly developing region. While it is agreed that SAM is a disease, it is most often not treated as such in East Asia and the Pacific, despite the existence of a cost-effective, WHO-endorsed approach for management of SAM (Integrated Management of Acute Malnutrition – IMAM). The implementation of at least one of its components (i.e. inpatient care of SAM, outpatient management of SAM, management of Moderate Acute Malnutrition (MAM) and community mobilisation) is feasible in all settings.

For every dollar invested in nutrition programmes, the return on investment is estimated to be US$48, US$44 and US$36 for Indonesia, Philippines and Vietnam, respectively (Horton & Hoddinott, 2014). Even if similar data are still being developed for IMAM programmes, the return on investment is most likely also high as well. Therefore, drastically reducing SAM, as well as other forms of malnutrition, is critical for national development. However, the vast majority of severely wasted children in East Asia and the Pacific will not receive treatment in 2016 and beyond if the current situation is maintained. Low levels of awareness and commitment to the issue have been identified as key factors for the lack of investment by both governments and cooperation partners in the prevention and treatment of acute malnutrition.

Opening a space for dialogue and governmental commitment

As part of a broader effort by UNICEF and partners to raise awareness and promote commitment to address acute malnutrition, a Regional Consultation on Prevention and Treatment of Severe Acute Malnutrition in Asia and the Pacific was held in Bangkok, Thailand, in June 2015. The meeting was organised by the UNICEF East Asia and Pacific Regional Office (EAPRO) with representatives from the governments of 13 countries (Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Mongolia, Myanmar, Pacific Islands countries (Vanuatu, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Fiji), Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Timor Leste and Vietnam), as well as development partners (UNICEF (country offices and headquarters), the World Food Programme (WFP), the World Health Organization (WHO), Action Against Hunger (ACF UK), Alive & Thrive, Save the Children, International Relief & Development (IRD), University of Louvain, Mahidol University and European Union). The objectives of the consultation were to discuss the latest evidence on nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive delivery platforms for the prevention and treatment of acute malnutrition; examine the strengths and challenges of the currently implemented SAM management approaches in East Asia and the Pacific; and identify the importance of acute malnutrition within the larger nutrition operating environment and the integration into national systems and existing coordination mechanisms at country level. At the end of the consultation, government representatives put forward a number of actions to be implemented in the short and long term (UNICEF, 2016).

This article summarises the key discussions held during the meeting, the general commitments made by countries to implement specific actions and a review of key activities carried out by one country (Myanmar; see Box 1) since the meeting, as a follow-up to those commitments.

IMAM in both emergency and development settings

East Asia and the Pacific is an emergency-prone region. The primary settings where IMAM services are often established and delivered are high-risk areas or in emergency situations. However, identification of IMAM as an emergency intervention has led to a lack of programme sustainability. Many IMAM programmes that are initiated in the onset of an emergency are often stopped once the emergency relief operations are over. Pilot programmes are often discontinued or never scaled up. Moreover, full integration of IMAM within the health system has not yet been achieved in any country of the region; the two main reasons are lack of national capacity in the national system to respond in these emergency-prone contexts and the consequent short-term planning of the emergency-based programmes. Yet the vast majority of children affected with SAM do not necessarily live in areas prone to disaster and are frequently concentrated in urban areas with large populations. Implementing IMAM exclusively in emergency contexts is limiting the improvement in coverage and quality and the expansion necessary to reach the almost six million new cases of children with SAM who are not being treated in the region each year. Hence, IMAM should be urgently institutionalised and prioritised in the development context.

At the same time, emergencies constitute an opportunity to expand and strengthen IMAM services and an entry point for longer-term, sustainable programmes. Governments are encouraged to take the lead in coordinating efforts among different stakeholders involved in IMAM and in bringing humanitarian and development sectors much closer together. These multi-sector and multi-stakeholder coordination efforts will be crucial to build resilient communities and systems that are less vulnerable to shocks.

Current status of IMAM in the region

At the time of the regional consultation on SAM, the vast majority of countries in East Asia and the Pacific were at initial stages of IMAM programme implementation. In spite of many countries having already included SAM into national maternal, newborn and child health policies and having prepared IMAM protocols, most of these are incomplete, out-dated or not approved. The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), Myanmar, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Vanuatu and Vietnam have already incorporated the 2013 WHO guideline updates on the management of SAM into their protocols. However, only two countries have officially endorsed them: DPRK and the Philippines (who endorsed National Guidelines on the Management of Severe Acute Malnutrition for children under five years in October 2015; see article in this issue of Field Exchange; Garg, Calibo, Galera et al, 2016). It is also expected that Myanmar will soon endorse an updated protocol.

Timor Leste is one of the few countries in the region that has introduced IMAM in all districts, while Cambodia, DPRK and Vietnam are in the process of scaling up their pilot interventions. Overall, significant improvements are needed to achieve more effective IMAM services and in particular to improve the overall quality and coverage (indirect coverage, programme coverage and geographical coverage) of the services. This calls for intensified advocacy efforts. The Philippines and Myanmar are planning to scale up their IMAM programmes, with a focus on institutionalising the treatment services, and most countries in the region have implemented both inpatient and outpatient SAM management services to varying degrees. However, Mongolia and Solomon Islands have only established inpatient care thus far, while Papua New Guinea and Cambodia are now beginning to establish services for both inpatient and outpatient care. Community-based platforms are not yet widely used in the context of IMAM in East Asia and the Pacific and will therefore require special attention in the near future.

With regard to public financing, much work is still needed in a region where many countries are still dependent on support for IMAM from development partners. Only three countries - Cambodia, the Philippines and Timor-Leste- have reported governmental contribution for supply funding. Cambodia and Timor Leste are also the only two countries that have incorporated ready-to-use therapeutic foods (RUTFs) on the essential medicines list (Vietnam has RUTF registered in the list of essential supplies but as a food, and is in the process of registering RUTF as a medicine so that it can be covered under the health insurance scheme).

Only three countries (Indonesia, Mongolia and the Philippines) have reported the inclusion of at least one SAM indicator in their Health Management Information System (HMIS); mainly by number of admission or screenings.

Challenges in East Asia and the Pacific

Some of the overall challenges to the implementation and scale-up of effective (high coverage and high quality) IMAM services are lack of policies and protocols, poor integration of IMAM services into the health system, limited investment from both governments and partners, lack of trained human resources in all areas (including remote and difficult to reach regions and population groups), weak information systems, limited and unstable availability and accessibility of essential medicines, and in some cases, a low level of awareness and commitment to the issue.

Specific challenges that prevent an optimal service delivery are the low quality of care, lack of patient-centred care, lack of community engagement, and lack of links with other health and nutrition services and community services. Countries in the region are at varying degrees and phases of integration of IMAM in standard health service delivery systems. In addition, most health information systems do not provide critical information about SAM.

In addition, a number of bottlenecks have been identified with relation to the management of supply and logistics, such as RUTF pipeline breaks, data problems, unpredictable funding, and delays and challenges in setting up local production of RUTF. Local RUTF manufacturing depends heavily on the import of ingredients1;and suffers from the lack of infrastructure and a weak legal framework. Misconceptions about local RUTF manufacturing, RUTF recipes and pricing are widespread. Increased competition of suppliers in the market has not resulted in price reduction. Another issue is RUTF storage conditions, which are often not adequate, leading to product deterioration and losses.

Integrating IMAM in the health system platform

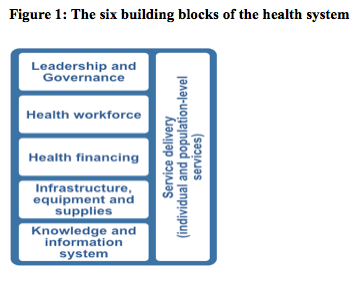

Given the large differences among health system delivery platforms of countries in East Asia and the Pacific, it is crucial that a context-specific approach to IMAM services delivery is designed and implemented for each country. Governments of the region are therefore encouraged to strategise and plan their IMAM approach through a health system strengthening lens, looking at opportunities to simultaneously strengthen the six building blocks of their health system while integrating IMAM management into them (Figure 1) as an initial step to achieve full institutionalisation of IMAM.

The linkage between IMAM and the first building block is established when governance, coordination and advocacy efforts that are crucial to ensure key IMAM actions, are integrated into the frame of the health system and sustained, such as integration of IMAM protocols into existing national policies, increase of governmental budget allocation for IMAM or incorporation of IMAM into other sectorial policies, such as food security or development policies.

Second, a physical and social coverage of the health workforce needs to be sustained, including their presence in urban and rural populations, and in remote and difficult to reach populations.

Third, the integration of IMAM into the financing system reflects the linkage with the health system’s second building block. This can be achieved through actions such as the creation of partnerships and consensus-building spaces at the political level, generation of evidence (including sound costing estimates), and preparation of valid statements regarding the rationale for the costs involved in the management of SAM.

Fourth, IMAM information systems need to be progressively incorporated within the health management information systems. Knowledge and information systems are extremely valuable to understand and address barriers to access.

Fifth, infrastructure, equipment and supplies for IMAM need to be embedded into national structures. In this framework, countries are encouraged to advance national processes for registration and listing of the products in their national medicine lists, given the large burden of SAM cases in the region.

Sixth, a number of minimum requirements for IMAM service delivery are considered essential and can be achieved through integration within the health system’s service delivery structure, including access for poor and difficult to reach populations, decentralised care, a basic package of health services that offer patient-centred care, quality of care, community engagement, or links with other health and nutrition services, and community services.

Linking IMAM components

Despite the fact that IMAM involves the management of SAM and MAM cases, linkages between these two components, as well as between outpatient and inpatient care, are often very poor in the East Asia and the Pacific region. In the first place, MAM management is generally not at all addressed, with the exception of certain short-term emergency contexts. Where MAM management is implemented, SAM and MAM management services are at times delivered by different platforms, or even different institutions, and effective referral mechanisms between both services are frequently missing (e.g. lack of coordination among health care providers at SAM inpatient care sites, outpatient care sites and MAM management sites). Among others, this lack of well-established linkages leads to situations where children whose health condition has deteriorated, are not referred from MAM to SAM services, or from inpatient to outpatient services, increasing the mortality rate in many instances.

Given the poor level of implementation and lack of linkages among the different IMAM components, the countries in the region are advised to strengthen the prevention strategies for acute malnutrition and their link to IMAM, through counselling and educational programmes that stimulate high quality infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices, and implementation of programmes of high quality and coverage that link disease prevention and treatment. While treatment strategies for SAM are well established, further evidence is still needed for prevention of acute malnutrition and management strategies for MAM in development settings, especially in infants younger than six months.

Including IMAM in the global, regional and national nutrition agendas

Governments of countries in East Asia and the Pacific will greatly benefit from considering IMAM in their regional and national nutrition agendas, and specially linking the acute malnutrition and stunting agendas. By addressing all forms of undernutrition with one package of interventions and using the same frameworks and strategies for prevention and treatment of stunting and acute malnutrition, governments will avoid duplication of efforts that might lead to increased budgets or unnecessary funding gaps. However, further articulation and refinement will still be needed with regard to the specific programmatic strategies for prevention of acute malnutrition, ensuring an optimal adaptation to development, fragile, and emergency contexts.

Future actions and commitments

At the end of the regional consultation, representatives from the participating countries committed to raise the SAM agenda in their respective context by highlighting their priority objectives and key actions to be undertaken during the following months. At the regional and country levels, future commitments focused on strengthening the design, implementation and monitoring of IMAM components, as well as the link among them, and the integration of IMAM services into the health system platform of each country.

More specifically, it was agreed that quality and coverage of inpatient and outpatient SAM management services was to be improved in all cases. Indonesia and some of the Pacific Island countries committed to develop up-to-date IMAM guidelines, while Cambodia, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Mongolia, Myanmar (see Box 1), Philippines (see article in this issue of Field Exchange; Garg, Calibo, Galera et al, 2016) and Vietnam committed to contextualise, update and/or finalise, with the latest available evidence, the IMAM protocols, guidelines, frameworks and action plans. It is worth noting that in Vietnam, the ongoing actions and future commitments include i) development and endorsement of national IMAM guidelines; (ii) formulation and local production of RUTF; (iii) piloting of IMAM in the five provinces; and iv) advocacy at central level for registration of therapeutic milk and RUTF as medicines and including these products and SAM treatment costs in the national health insurance scheme. The Vietnam case will be documented upon achievement of key milestones of this IMAM scale up approach. Moreover, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Myanmar and Pacific Island countries committed to roll out the above-mentioned IMAM guidelines and protocols. It was agreed by participants that IMAM protocols should correctly reflect the four components of services, even if one or several of the components cannot currently be implemented in a specific context. In addition, it was discussed that protocols should include both technical and operational components and should be written in a simplified, user-friendly and practical manner. Protocols should also include a vision for scale-up, using a phased but integrated approach. Experts also emphasised the importance of strengthening community mobilisation through community empowerment and community systems strengthening, optimising the use of existing platforms and structures to integrate IMAM. In those countries where community-based structures and programmes are absent, it was recommended that service delivery at health facility level should be effectively implemented.

Many of the discussions revolved around the importance of scaling up IMAM services in both humanitarian and development contexts. It was agreed that areas with high burden or high prevalence of SAM should be targeted. A number of representatives from countries (Cambodia, Myanmar, Philippines and Vietnam) and from UNICEF country offices (DPRK) committed to prepare during 2015 and 2016 all necessary actions for scaling-up the IMAM services throughout the country, including ensuring that IMAM features in the agenda of the multi-sectoral coordination platforms in SUN countries.

In parallel to the integration of IMAM into the health system building blocks, it was agreed that governments were to prioritise heath system strengthening. This will allow institutionalisation of IMAM within the country’s health system, which in turn will also facilitate scale-up of services. While Lao People’s Democratic Republic committed to integrate SAM in the pre-service curricula and Vietnam planned to integrate IMAM services in the health essential service package reimbursed by the health insurance scheme, representatives from UNICEF DPRK committed to scale up IYCF counselling services alongside IMAM to hospitals in 90 counties.

The majority of countries present in the consultation announced their plans to carry out capacity building activities targeted to health care personnel, through trainings (i.e. Myanmar, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Mongolia, Philippines, Timor-Leste, Pacific Island countries, Papua New Guinea, DPRK and Cambodia) or on-the-job coaching activities (Timor-Leste, Myanmar, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, DPRK).

A large number of countries (DPRK, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Mongolia, Philippines, Timor-Leste) committed to establish a nutrition supply chain system for SAM treatment, while Cambodia, Philippines and Papua New Guinea committed to advocate and/or ensure the inclusion of SAM commodities in the national list of essential drugs. Participating countries also showed their commitment to identify contextually appropriate approaches for SAM and MAM management, including the distribution of context-specific specialised nutritious foods and/or cash. While Indonesia and Philippines are planning to explore and identify opportunities for local production of RUTF, Cambodia and Mongolia shared their plans to identify alternative local recipes of Ready to Use Foods, as well as increasing accessibility of these foods through mapping of potential producers (both national and international).

It was also generally agreed that a strong focus should be put on the collection of the right type and amount of information, and all gathered information should help to understand and address barriers to access to treatment. While some countries (Timor-Leste, Papua New Guinea, DPRK and Lao People’s Democratic Republic) decided to focus on the inclusion of IMAM indicators in the national Health Management and Information System (HMIS), others (Indonesia, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Cambodia, Timor-Leste and Cambodia) committed to focus their efforts in strengthening the National Information System or the nutrition-related monitoring and evaluation system. The bottleneck analysis approach can be used and adapted to improve the quality and coverage of services. Cambodia and Philippines committed to strengthen the IMAM programme performance through bottleneck analysis, evaluation or review of existing services.

During the consultation, it was agreed that the policy and advocacy components of SAM prevention and management programmes should be systematically addressed in the entire region, requiring consensus building, the collection of various type of evidence, and the establishment of partnerships. For example, representatives from Fiji committed to create an advocacy strategy to support advocacy for child nutrition, including IMAM, at all levels of government. In addition, Lao People’s Democratic Republic shared their commitment to implement advocacy activities so that a costing analysis of SAM can be carried out, while Cambodia and Indonesia committed to focus their efforts on data analysis, so that evidence can be generated with regard to the prevalence of SAM in the different contexts. Key advocacy messages to be shared in the region during the coming years will include the need to reposition SAM as a disease, the right of children to receive treatment, and the need to include SAM in the global and regional nutrition agendas, including the message that acute malnutrition can be a contributing factor to stunting.

Despite the fact that countries were encouraged to integrate the cost of IMAM into the different financial systems at national and sub-national levels, no country committed to do so in the short term. While experts will continue to advocate for the design and implementation of prevention programmes that encompass both nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions, Timor-Leste and Mongolia committed to establish cross-sectional linkages so that all underlying causes of malnutrition are clearly addressed. Mongolia, Lao People’s Democratic Republic and Cambodia committed to create synergies between maternal and infant and young child nutrition, IMAM, supplementation of vitamins and minerals, as well as nutrition in emergencies.

For more information, contact: Christiane Rudert, Regional Nutrition Advisor, UNICEF EAPRO,

Box 1: Experiences of Myanmar

By Jennifer Hilton, Public Health Nutrition Consultant, and Hedy Ip, Nutrition Specialist, UNICEF Myanmar.

The Government of Myanmar has included the management of acute malnutrition as part of the essential package of health services. Over the past two years, with technical support from partners, national IMAM protocol and guidelines have been developed and Myanmar is gearing up to roll-out IMAM in 2016. The first phase of roll-out will cover high burden areas in key states/regions with the aim of reaching state-wide coverage over the next years.

At the regional SAM consultation in June 2015, participants from Myanmar defined specific objectives to reach this goal, outlining key steps, identifying main stakeholders and their roles, as well as support that would be required. These related to finalizing guidelines and securing government endorsement; implementation and monitoring of integrated IMAM services at selected pilot states/regions in 2016; and phased scale up to remaining states/regions (at least to all state/regional hospitals) by end of 2016.

Myanmar held national elections in November 2015 and is currently in a transition period as the new Government takes over in April 2016. Given this context, some delays were experienced due to competing priorities, however Government remained committed to continue moving forward with planning of IMAM roll-out. Actions under Objective 1 and some actions under Objective 2 have been completed as of early 2016. Remaining commitments are expected to be met during 2016 and completed by end of the year. The roll-out of trainings will take place after April when the new Government is in place.

Key highlights of success include the bringing together of a wide range of stakeholders across Government departments, universities, UN agencies and NGOs in support of a common national IMAM roll-out strategy and the inclusion of operational strategies for high prevalence and low prevalence contexts and specific age groups (e.g. older children), which are specific to the context of Myanmar. The roll-out of IMAM will closely follow the roll-out of new national community-IYCF guidelines, which already began at the end of 2015. This will build capacity of health workers across key intervention areas of nutrition and provide an opportunity for integration, in terms of service delivery, community mobilisation, supportive supervision and monitoring. In light of any structural reforms that may take place this year under a new Government, key areas of focus that need to be prioritised in the coming months include coordination, referral and follow-up mechanisms between different Government health departments and partners, and community engagement and outreach services in areas where human resources may be limited.

References

1 Powdered ingredients (e.g. milk powder, vitamins and minerals) embedded most frequently in a lipid-rich paste (e.g. vegetable oil, sugar, peanuts, beans, roasted sesame seeds, cowpeas, amaranth, roasted rice flour, roasted pearl barley flour, roasted maize flour, roasted chick pea flour), but can also be produced in solid or drinkable forms.

Garg A, Calibo A, Galera R, Bucu A, Paje R, and Zeck W, 2016. Management of SAM in the Philippines: from emergency-focused modelling to national policy and government scale-up. ENN Field Exchange 52, May 2016.

Horton S, & Hoddinott J, 2014. Food security and nutrition perspective paper: Benefits and costs of the food security and Nutrition Targets for the Post-2015 Development Agenda. Post-2015 Consensus. Copenhagen Consensus Center. Accessed January 16, 2016.

Olofin I, McDonald CM, Ezzati M, Flaxman S, Black RE, et al (2013). Associations of Suboptimal Growth with All-Cause and Cause- Specific Mortality in Children under Five Years: A Pooled Analysis of Ten Prospective Studies. Plos One 8(5): e64636

UNICEF 2016. Prevention and Treatment of Severe Acute Malnutrition in East Asia and the Pacific. Report of a regional consultation. Accessed April 12, 2016.

UNICEF, WHO & World Bank 2015. Joint child malnutrition estimates - Levels and Trends. UNICEF-WHO-The World Bank.