Integrated protocol for severe and moderate acute malnutrition in Sierra Leone

Summary of research1

Location: Sierra Leone

What we know: Impliementing separate protocols for MAM and SAM treatment can be administratively cumbersome in emergency settings.

What this article adds: A cluster-randomised controlled trial in Sierra Leone explored whether integrated MAM and SAM treatment improves recovery rate and community coverage. A total of 1,957 children under five years of age were enrolled and randomly assigned to integrated treatment (decreasing RUTF dose for SAM, LNS for MAM, limited duration of treatment, no routine medication, peer counselling) or standard treatment (government protocol, RUTF for SAM, CSB for MAM, micronutrient supplementation and prophylactic antibiotics). Different anthropometric enrolment criteria and de?nitions of recovery were used by the study arms that limit direct comparison of SAM/MAM outcomes. Most of the children receiving integrated treatment were MAM cases (70%), were younger, had higher WHZ on enrolment and less oedema. For standard treatment, 63% were SAM. Coverage was 71% for integrated and 55% for standard care (P=0.0005). GAM recovery was 83% for integrated and 79% for standard treatments. Care group participation was associated with a greater recovery rate. Loss to follow-up at six months after recovery was high for both arms (45%), which limited further planned analyses. The findings suggest that integrated care may be an acceptable alternative to standard care in emergencies; care should be exercised in extrapolating the ?ndings to other contexts.

Global acute malnutrition (GAM) is the sum of moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) and severe acute malnutrition (SAM). It is common in developing countries and is found in approximately 8% of children worldwide. Management of malnutrition is often assisted by the UN agencies; however there is division of labour and responsibility for the two forms of acute malnutrition (WFP for MAM and UNICEF for SAM), which means that use of different foods and separation of treatment protocols for MAM and SAM treatment can be administratively cumbersome in emergency settings. This paper describes a clinical trial in post-conflict Sierra Leone before the advent of the Ebola outbreak of 2014 to test the hypothesis that integrated MAM and SAM treatment would result in an overall higher recovery rate and provide higher community coverage than the standard separate MAM and SAM treatment programmes.

Method

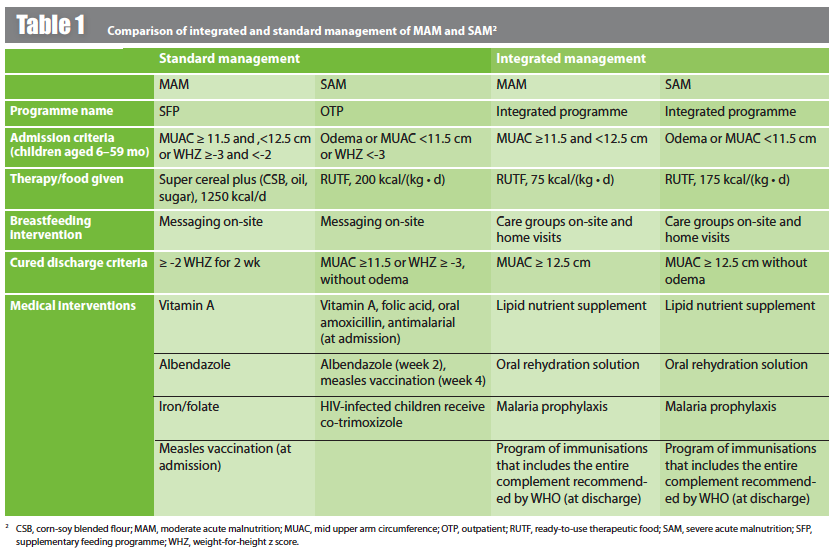

This study was a cluster-randomised controlled trial in Sierra Leone conducted in ten centres treating GAM in children aged 6-59 months. Children were randomised for up to 12 weeks treatment in an integrated (five centres) or standard programme (five centres). Catchment areas for both programmes were similar. A sample size of 900 children was planned for each study arm. The integrated protocol used the presence of bipedal oedema and/or mid upper arm circumference (MUAC) <12.5 cm to identify SAM, and MUAC alone for MAM. The standard protocol used MUAC, oedema and WHZ criteria (see Table 1 for details). For both approaches, where appetite was inadequate, the child was admitted for inpatient treatment.

The integrated protocol included a decreasing ration of ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF). Children returned for follow-up every 14 days. An RUTF ration suf?cient for two weeks was dispensed if the child had not recovered. When a child with SAM gained suf?cient MUAC to be classified as MAM, the ration of RUTF was reduced. After a child had received six rations of RUTF over 12 weeks but had not recovered, he or she was deemed as having remained malnourished, no further RUTF was given and they were referred for medical evaluation. This de?nition of remaining malnourished was chosen because in previous work, >95% of children reached their outcome by week 12, and no further improvement was seen between weeks 12 and 16 of feeding. Children who recovered received no more RUTF, but instead were given 500g of a lipid nutrient supplement (LNS) that provided 100% of the RDA for all micronutrients and 200 kcal/d when taken as 40 g/d. All caretakers were referred to a clinic-based care group (mother peer-counselling group) that focused on a variety of child nutrition and health issues, including improving breastfeeding practices.

The standard therapy protocol (as per government guidelines) treated MAM children with a fortified blended flour, treated SAM children with RUTF (according to the national protocol in Sierra Leone) and used weight-for-height Z score (WHZ) criteria to determine admission and discharge to the treatment programme. Follow-up occurred weekly until the child had a WHZ of more than -2 for two consecutive visits. There was no limit to duration of treatment. No peer counselling was provided. Table 1 summarises the components of the integrated and standard protocols for the management of GAM.

The primary outcomes were coverage and recovery rates (recovery rates were not directly comparable because recovery was defined differently in the two study groups). Coverage was de?ned as the fraction of children receiving treatment for malnutrition among all those who were eligible. This was determined by a coverage survey conducted in each of the ten centre catchment areas using the Simplified LQAS (Lot Quality Assurance Sampling) Evaluation of Access and Coverage (SLEAC) sampling design.

Data analyses

Data were double-entered in Microsoft Access. Anthropometric indexes were based on the WHO 2006 Child Growth Standards, calculated by using Anthro version 3.22 (WHO) and AnthroPlus version 1.0.4 (WHO). Comparisons of enrolment characteristics between study groups were made by using Fishers exact test for categorical variables and Students t test for continuous variables. P values <0.05 were considered to be signi?cant

A direct comparison of recovery rates was not possible because recovery was de?ned differently in the two study groups, so a CI was calculated by using a one-sample Z test to convey a sense of how often the schemes succeeded with the children they enrolled. Comparisons of weight gain, MUAC gain, number of clinical visits and ?nal WHZ between both programmes were made by creating linear regression models. Coef?cients with P values <0.05 were considered to be signi?cant.

Results

A total of 1,957 children were enrolled in the study. The study arms had disparate baseline characteristics, partly due to the different enrolment and recovery rate definitions used by the study arms, so direct comparisons of outcomes are difficult. The children who received integrated management were younger than those receiving the standard management, with a higher WHZ upon enrolment, were less likely to be oedematous and more likely to report a fever. Most of the children receiving integrated management had MAM (774 of 1,100; 70%); whereas among those receiving standard management, SAM predominated (537 of 857; 63%; P = 0.0001).

Coverage was 71% in the communities served by integrated management and 55% in the communities served by standard care (P = 0.0005). GAM recovery in the integrated management protocol was 910 of 1,100 (83%) children and 682 of 857 (79%) children in the standard therapy protocol.

Children who received integrated management recovered more quickly with greater MUAC gain and a higher WHZ on completion. Children who received standard management had greater rates of weight gain. The loss to follow-up at six months was high (55% return rate for both treatments).

The cost of RUTF used to treat a SAM case in integrated management was US$36, whereas for the standard management of SAM it was US$68 (this difference relates to the reducing dose and limited period of RUTF use (12 weeks) in the integrated programme). The cost of supplementary food used to treat a case of MAM in either the integrated or the standard management scheme was US$12.

Discussion

To allow for some comparisons, linear regression modelling was used to examine the 95% confidence intervals of the proportions measured in each group separately for recovery. The authors speculate that the larger proportion of MAM cases (and hence shorter recovery time) in the integrated management system was due to the caregivers actively seeking treatment earlier on in their child’s process of malnutrition; perhaps because they believed the care would be more readily available in this delivery system.

The authors observe that care group participation was associated with a greater recovery rate, suggesting that reinforcing good nutrition and hygiene practices may be a useful adjunct to feeding programmes among children with GAM. The differences in weight gain seen between the two groups are attributable to the more severe wasting seen in the standard therapy group (and hence will have greater rates of weight gain when treated). The greater coverage rates seen in the integrated management group may be due to the more consistent nature of the clinical service and no stock-outs. Better understanding by the mothers that their child would be assessed and treated for both MAM and SAM by attending the integrated clinic may also have contributed to the higher coverage rate in this group.

The high rate of loss to follow up (at six months) prevented analysis of the effectiveness of the LNS and simple infection control measures that were given in the integrated management group. Comparisons of cost-effectiveness of the two management schemes could not be made because many of the costs of care were not documented; reduced food cost and simpler logistical requirements of the integrated model are likely to make it less costly to implement, per child treated.

The paper concludes by suggesting that an integrated management scheme for GAM may be simpler to implement in humanitarian crises. The use of a single food product simplifies logistics, the exclusion of additional micronutrients makes delivery of care easier and the exclusive use of MUAC as an anthropometric index may be easier for local health aids to master. This study showed that integrated management of GAM in children is an acceptable alternative to standard management, with similar recovery rates and greater community coverage. The authors advise that care should be exercised in extrapolating the ?ndings to other contexts.

References

1 Maust A, Koroma AS, Abla, C., Molokwu N, Ryan KN, Singh L & Manary MJ. (2015). Severe and moderate acute malnutrition can be successfully managed with an integrated protocol in Sierra Leone. Journal of Nutrition 30 September 2015. doi: 10.3945/jn.115214957