Bangladesh Nutrition Cluster: A case in preparedness

By Andrew Musyoki and Anuradha Narayan

By Andrew Musyoki and Anuradha Narayan

Andrew Musyoki is a Nutrition Specialist with UNICEF Bangladesh

Anuradha Narayan is the Chief of the Nutrition Section, UNICEF Bangladesh.

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial contribution of ECHO and UNICEF in the implementation of the cluster project. The contributions and work of all cluster partner member organisations is highly appreciated. Special thanks to the case study working group members comprised of ACF, WFP and SCI.

The ENN team supporting this work comprised Valerie Gatchell (ENN consultant and project lead), with support from Carmel Dolan and Jeremy Shoham (ENN Technical Directors). Josephine Ippe, Global Nutrition Cluster Coordinator, also provided support.

The authors would like to thank all Nutrition Cluster (NC) partners for their work and acknowledge the NC working group that supported the development of this article: Dr. Ojaswi Acharya, Head of Department, Health and Nutrition, Action Contre La Faim (ACF) Bangladesh; Dr. Golam Mothabbir, Senior Advisor, Health and Nutrition, Save the Children Bangladesh; Rachel Fuli, Head of Nutrition, World Food Programme Bangladesh; and Dr. Alamgir Murshidi, Institute of Public Health Nutrition (IPHN), Government of Bangladesh.

This article is a summary of a case study produced through a year-long collaboration in 2015 between ENN and the Global Nutrition Cluster (GNC) to capture and disseminate knowledge about the Nutrition Cluster experiences of responding to Level 2 and Level 3 emergencies (available at www.ennonline.net/ourwork/networks/gnckm). The documented findings and recommendations are those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of UNICEF, its Executive Directors or the countries that they represent and should not be attributed to them.

Location: Bangladesh

What we know: Bangladesh is partcularly prone to natural disasters, such as cyclones and floods. Acute and chronic malnutrtion are prevalent.

Wha this article adds: In 2012, the Government of Bangladesh (GoB) estalished a non-IASC national cluster system for all sectors focused on emergency preparedness. A Nutrition Cluster Coordinator provides both technical support to UNICEF programming (inlcuding SAM treatment scale up) and coordination (<50% time). Strategic areas of focus are nutrition coordination, assessment, information management, capacity development, nutrition programme support and cross-sectoral engagement. Challenges include district levels gaps in data collection and coordination capacity; lack of funding for preparedness; absent community based SAM treatment; and lack of a muti-sectoral framework. Sub-national clusters have been effectve in response, partnerships with academic institutions have enabled traning, assessment and capacity development. Coordination is currently in transition to develop one national streamlined forum to coordinate nutrition programming.

Country overview

Bangladesh has the highest percentage of its total land area and 97.7% of its population at risk of multiple hazards (World Bank, 2005). The country also has the second-highest absolute and relative mortality risk for floods (UN, 2009). Over 20 districts are highly vulnerable to cyclones, floods, flash floods and water-logging. Bangladesh also has persistently high levels of acute malnutrition (wasting) across the country, with a national average of 14% global acute malnutrition (GAM), of which 3% is severe acute malnutrition (SAM). Stunting is 36% nationally and underweight is 33%. While stunting decreased from 51% to 41% over 2007 to 2011, Bangladesh is unlikely to meet the World Health Assembly target of a 40% reduction in stunting of children under five years of age by 2025. The exclusive breastfeeding rate significantly decreased from 2011 (65%) to 2014 (55%), while quality and diversity of meals for children aged 6-23 months is low (Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey, 2014). Prevalence of anaemia in pre-school age children is at 33.1% and 26.0% among pregnant and lactating women (National Micronutrient Survey, 2013).

History of the Nutrition Cluster (NC)

The Nutrition Cluster (NC) in Bangladesh was initially activated in 2007 in response to Cyclone Sidr. However, unlike other clusters, no dedicated NC coordination staff were put in place (UNICEF nutrition staff chaired a few initial national-level cluster meetings), and there was no consolidated NC response plan. NC partners, including UNICEF, WFP and a few national and international non-governmental organisations (NGOs) implemented responses mainly related to IYCF, blanket supplementary feeding and targeted distribution of multiple micronutrient powders in cyclone-affected areas. Programme discussions were held in the Nutrition Working Group (NWG) meeting, an information coordination group recognised by both the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) and the Institue of Public Health Nutrition (IPHN), co-chaired by UN agencies and NGOs.

During this time it became clear that national emergency response experience was very limited. Not one of the 36 local NGOs prequalified by the UN agencies to undertake emergency response had the capacity to respond to nutrition. While some nutrition policies provided structure and guidance for emergency response (such as the IYCF and anaemia strategy), there was an absence of guidance on management of acute malnutrition, assessments and supplementary feeding.

A UNICEF-commissioned review, four months post-SIDR, recommended actions for preparedness and suggested how national and sub-national level coordination structures should be organised and led (and by which government body), with support from UNICEF. Recommendations were not reflected in subsequent UNICEF and government plans due to ongoing discussions on how to harmonise nutrition functions across the government (IPHN, the Nutritional Nutrition Programme (NNP) and MoPH). Additional analysis conducted by UNICEF in 2012 again documented gaps in nutrition emergency response capacity and preparedness. These were:

- Weak pre-crisis/routine nutrition programming within government facilities, including mainstreaming of proven direct nutrition interventions into the existing health system, especially management of SAM.

- Inadequate nutrition information systems for routine monitoring at national and subnational levels (including acute malnutrition).

- Low capacity of service providers, cluster members and partners in Nutrition in

Emergencies (NiE), including area-based nutrition assessment, planning and response.

- Lack of national guidelines on area-specific nutrition assessments.

- Weak orientation of district and sub-district authorities on NiE.

- Lack of strong coordination within the nutrition sector in general, impeding linkages between development and humanitarian actions.

In August 2012, after years of advocacy and lobbying by humanitarian actors (including donors) for a formal mechanism to address NiE and preparedness, the Government of Bangladesh (GoB) established a national cluster system for all sectors to focus on preparedness for a predictable response (this is not an IASC-mandated cluster system, but one mandated by the GoB). For nutrition, this mandated mechanism complements other nutrition coordination forums such as the UN Ending Child Hunger and Undernutrition Partnership (UN REACH), Scaling Up Nutrition movement (SUN) and the NWG. UN REACH works on upstream nutrition advocacy issues, bringing together the different UN agencies and supporting the SUN movement. The NWG brings together nutrition stakeholders to discuss and share emerging issues in nutrition. The NC is a member of the NWG and has been engaged in the preparation of advocacy documents, such as the common narrative on undernutrition in Bangladesh produced by UN REACH.

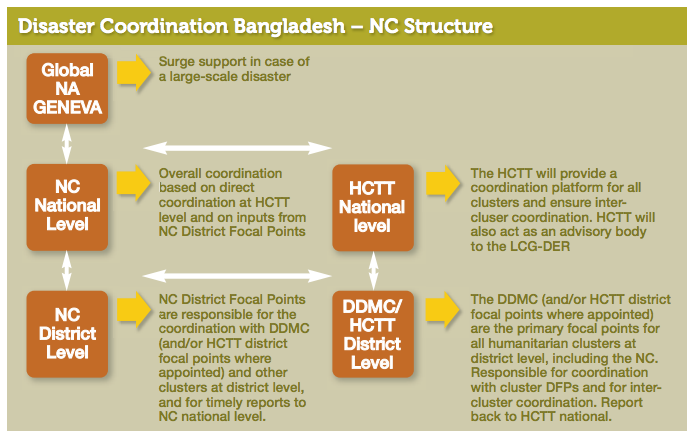

Bangladesh Nutrition Cluster: purpose, national and sub-national governance and funding

The aim of the NC in Bangladesh is to support the GoB in the coordination of effective emergency preparedness and response to humanitarian crisis that meets core commitments and standards, through strengthening the collective capacity of humanitarian actors working in the area of nutrition in Bangladesh. The structure is outlined in Figure 1. The NC operates under the Government’s policy body for emergencies, the Local Consultative Group-Disaster Emergency Response (LCG-DER). The LCG-DER is mandated to ensure effective coordination of the national and international stakeholders in the broader scope of disaster management (risk reduction, preparedness, relief/response and recovery/ rehabilitation) and is the central forum for decision-making on disaster management. Under the LCG-DER is a Humanitarian Coordination Task Team (HCTT), a government body that functions in a similar way to the Humanitarian Country Team (HCT) mechanism in IASC cluster countries. The HCTT is led by the UN Resident Coordinator (UNRC) with a co-chair from the Ministry of Disaster Management (MoDM). Membership of the HCTT is composed of all cluster leads, a representative of the NGOs and donor agencies (European Commission Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection Department (ECHO) and DFID).

Figure 1: Disaster Coordination Bangladesh – Nutrition Cluster Structure.1

1NC: Nutrition Cluster; HCTT: a Humanitarian Coordination Task Team; DDMC: District Disaster Management Committee; DFP: District Focal Point

The NC focuses particularly on preparedness and is available to provide support to the GoB and LCG-DER in times of both slow and sudden-onset emergencies. For example, the NC provided support to people affected by floods in Satkhira district through blanket supplementary feeding to over 1,000 beneficiaries.

UNICEF and the IPHN, which sits under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW)1, co-chair the National Cluster. The NC consists of over 15 member organisations, including UN agencies, international and local NGOs, national institutes and research/academic institutions. At sub-national level, the civil surgeon leads the district-level nutrition coordination, while UNICEF’s District Nutrition Support Officers (DNSO) act as facilitators and co-lead.

The national NC has two working groups focusing on acute malnutrition and assessments; IYCF issues are addressed by the active IYCF alliance movement in Bangladesh. Other working groups are established as needed. There are clear lines of communication from district to national level in the event of a disaster.

In addition to emergency response coordination, sub-national NC forums are used to further the agenda of mainstreaming Direct Nutrition Interventions (DNIs) into the health sector and to engage other sectors in nutrition-sensitive interventions. DNSOs have actively been engaging multi-sectoral partners (including health, education, agriculture and water) in routine coordination meetings to identify and address bottlenecks to mainstream DNIs; to set DNI targets and to review progress.

The dual focus of emergency response coordination and routine district nutrition programming was determined the most cost-effective use of district resources.

The NC in Bangladesh is managed by two UNICEF nationally based, full-time staff, an NC Coordinator (NCC) and an Information Management Officer (IMO). Both provide technical support to UNICEF’s Nutrition Programme (>50% time) and support to NC activities and coordination. The NCC is also the focal point for the scale-up of management of SAM and is in charge of nutrition mainstreaming in the field, providing day-to-day technical support and supportive supervision to over 40 field-based nutrition staff.

The NC has been largely funded by ECHO since 2013 with co-financing from UNICEF (annual 2015 budget: 0.5 mllion USD). UNICEF is funding the sub-national cluster coordination through internal resources. Cluster partner organisations have also contributed staff time in some of the cluster activities.

NC strategy

The NC has six strategic areas of focus, elaborated below:

Nutrition coordination

At the national level, the NC has developed and routinely updates cluster documents, including a “4W mapping” (who, what, when and where), cluster contingency plan, and cluster contact list. The national NC organises monthly cluster and ad hoc meetings, provides orientation on coordination for district-level cluster focal points, supportive supervision during initial meetings, and ongoing technical support and mentoring to government and partners.

The sub-national NC has trained over 300 members of disaster management committees on NiE interventions in 16 disaster-prone districts. The sub-national NC actively supported post-Cyclone Viyaru relief efforts in Barisal and Chittagong divisions in May 2013; nutrition coordination forums were organised and partners were assigned operational areas to avoid duplication of efforts.

Nutrition assessment

In 2013 it was recognised that the lack of a standardised methodology/guideline for implementing small-scale, area-based nutrition surveys was resulting in poor data quality and challenges in comparing assessments and monitoring over time. In response to identified gaps (2013 needs assessment), the cluster organised a training course on the SMART methodology for 17 partner staff. The Rapid Nutrition Assessment Team (RNAT) was subsequently formed, comprised of national staff and housed within Dhaka University’s Institute of Nutrition and Food Science (INFS). The RNAT has since carried out three localised nutrition surveys and has supported other organisations to implement surveys. The team is available for quick deployment to any disaster-affected area to carry out nutrition assessment and individual staff may be hired by agencies. In non-response time, the team has worked to integrate the SMART methodology into the nutrition curriculum for undergraduate students.

The NC has also supported the GoB to develop National Nutrition Assessment guidelines based on the SMART methodology. An Assessment Working Group has been formed to support organisations to conduct quality nutrition surveys.

Nutrition information management

The NC has focused on improving the availability and utilisation of nutrition information. NC advocacy resulted in the establishment of the Nutrition Information and Planning Unit (NIPU) at the IPHN, which saw to the inclusion of standard nutrition indicators in the Health Management Information System (HMIS). District coordination meetings have also contributed to the improved availability of data. Data are published by the NIPU in reader-friendly “nutrition bulletins” (two issues have been printed to date), which are circulated among district and national stakeholders. While this reflects progress, the NC has had limited engagement in overall information management for preparedness in response.

Capacity development

To address traning needs identified in 2013, the NC, in partnership with Helen Keller International (HKI) and INFS of Dhaka University, contextualised the Global Nutritino Cluster’s Harmonised Training Package (HTP) for NiE for Bangladesh. This package was then used by INFS and UNICEF to roll out trainings in ten disaster-prone districts and among partner staff at national level. Partners have also used the materials to train staff countrywide. Collectively, more than 400 people have been trained, most of whom are members of district disaster management committees (DMC). The cluster plans to reach an additional 175 partner staff with NiE training and 150 members of DMCs in 2015.

Discussions with other sectors, such as Food Security, WASH (water, sanitation & hygiene) and health, indicate gaps in knowledge on NiE issues. To address this, the NCC has advocated with other clusters to integrate key issues on NiE in their training packages. With support of the IMO, nutrition indicators have been added to the Food Security Cluster’s assessment tool. The IPHN has also integrated NiE in its five-day, basic nutrition training package for frontline government health workers in community clinics and sub-district hospitals.

NiE interventions are now included in the National Nutrition Policy and the national operational plan of the IPHN incorporates NiE as an area of focus. The contextualised HTP has also been incorporated into the government’s basic nutrition module aiimed at frontline health workers.

Working with multiple stakeholders and pushing the nutrition agenda has been challenging. Additionally, significant follow-up is required to ensure that the NiE materials incorporated in different areas are utilised in the correct way.

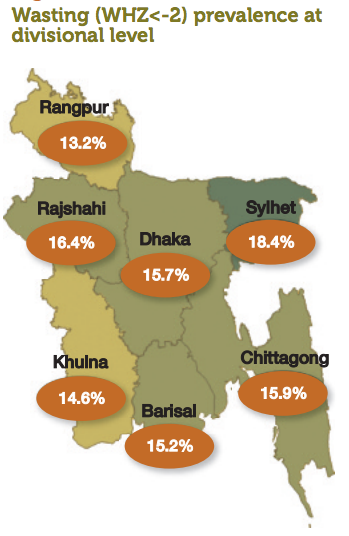

Figure 2: Wasting (WHZ<-2) prevalence at divisional level

Nutrition programme support

For many years, management of SAM has been led by NGOs due to the absence of nationwide programming within government-led facilities. Due to the geographical focus of NGOs, SAM programming has been limited to pockets in certain districts, despite the relatively even distribution of wasting throughout the country (see Figure 2). The NC has therefore focused on supporting the management of SAM given the high burden in Bangladesh a nd the extremely limited capacity in this area.

While national guidelines on the management of SAM were approved in 2008 and all districts are now implementing inpatient treatment of SAM (to varying degrees), the Government has yet to approve a strategy for rollout. Additionally, as the GoB does not allow the use of Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Food (RUTF), community management of SAM is impossible. The NC and UNICEF have therefore focused efforts on capacity-building, supply provision and the development of a database for inpatient treatment, while WFP has focused on the management of MAM.

To expand SAM programming, the NC has supported the MOHFW to scale up SAM management through dedicated use of the NCC’s time and the coordination support from the Acute Malnutrition Working Group (AMWG) comprised of the GoB and NGO partners. The AMGW has reviewed SAM management tools and guidelines and implemented a bottleneck analysis (conducted in collaboration with IPHN) addressing identified issues. The NCC reviews monthly SAM reports regularly and provides feedback to implementing teams. The NCC and AMWG also provide ongoing technical support to public health facilities.

At national level, the NC has supported the establishment of a database housed and managed by IPHN. Discussions are at an advanced stage to incorporate the SAM reporting tool in the HMIS. A training of trainers at central level has been conducted and over 1,000 government health workers in 102 hospitals have been provided with on-the-job training in inpatient SAM management. This represents 76% of all hospitals targeted for SAM management (21% of all hospitals in the country). Submission of monthly reports has improved by 50% (from less than 30% to over 80% of facilities submitting reports). Consequently, the number of facilities providing inpatient management of SAM has been scaled up from five facilities at the start of 2013 to 134 by end of 2014.

The main challenges to the scale-up of SAM management include lack of rollout strategy; low capacity of health workers on inpatient management; absence of community-based option due to ban on RUTF importation (government policy) and no local production; health worker motivation to take on the burden of SAM treatment; and regular and accurate reporting.

Work is needed to ensure that performance indicators are maintained at desired levels and capacity development initiatives for health workers continue since the trainings so far have reached a small percentage of health workers. Coverage and access to SAM management services remain low since the community based option is not avalable. and only about 30% of government hospitals offer services.

Cross-sectoral engagement

The NC actively collaborates with other clusters and humanitarian coordination team activities. In addition to district level work, the national NC has collaborated with the Food Security Cluster on assessment initiatives, including the Integrated Phase Classification (IPC). The NC has supported planning, training, field data collection, analysis and reporting of nutrition surveys, which have fed into the IPC analysis. In collaboration with the IPC, the NC conducted the very first IPC nutrition pilot in 2014 that has provided the foundation and informed subsequent pilots globally. IPC analysis maps have informed prioritisation of most vulnerable areas for programming and applied in ranking the most needy areas whenever a joint needs assessments (JNA) is under taken. The NC has also engaged actively in the JNA of the HCTT with data collection, reporting and response.

The NC participates in sectorial coordination mechanisms such as the NWG and food security and WASH (water, santation & hygiene) clusters. The NC has collaborated with the WASH and Food Security Clusters to develop a joint emergency response plan which was used following flooding in 2013 to channel funding for both WASH and food security interventions.

While UN REACH is represented in the NC, the NC has not had any meaningful interaction with the SUN movement in-country. This is largely due to the fact that SUN architecture is located at a high level within government and at a level where the NC is not represented.

Challenges

Capacity gaps remain. While district nutrition coordination is improving in the 16 target districts, huge technical capacity gaps remain among health workers on collection, analysis and utilisation of data. Many facilities have limited nutrition services and are not reporting nutrition indicators or are not capturing data accurately. Additionally, coordination gaps are evident in non target districts. While there has been considerable training undertaken, it remains to be seen if this translates into actual capacity to respond in a future emergency.

Building preparedness capacity in high burden and high-risk context requires long-term funding. The cluster has received limited funding for its preparedness activities (e.g. capacity-building of DMCs) and thus these have been implemented in a phased manner.

Coverage of SAM treatment is limited due to the lack of community services for managing SAM. Given the huge burden of SAM in Bangladesh, scale-up of outpatient therapeutic services to the community level is necessary.

Sustaining interest in the cluster mechanism and preparedness efforts in a development context is a continuing challenge. The NC does not have influence on funding for disaster/emergency response as is the case in IASC-activated clusters, where there is mobilisation of resources around the costed Humanitarian Response Plan.

Additional funding is needed to sustain and increase sub-national coordination and expand treatment of SAM. UNICEF has been advocating for pooled funds to address these nutrition gaps.

Cross-sectoral engagement and advocacy has been challenging, particularly in the absence of a policy document on nutrition-sensitive actions or a framework on how this could be facilitated.

Learning

Key lessons emerging include:

- The provision of technical support by the NCC to routine UNICEF programming is time-consuming and has taken priority over the core responsibilities of the cluster. This has resulted in a missed opportunity to build greater emergency preparedness.

- While the NC has built capacity in information systems for nutrition and nutrition assessments, work remains to be done in information management for preparedness.

- While momentum and advocacy for linking emergency and development approaches for nutrition preparedness and programming is building at national level through the UN REACH and SUN movement, guidance documents and a policy framework are essential to forge these links and inform actors involved in nutrition-sensitive programming.

- Leveraging other sectors to implement nutrition-sensitive activities is challenging due to time required and lack of evidence and guidance on how to do this effectively. UNICEF is increasing efforts to engage with the SUN secretariat in Bangladesh to define and address multi-sectoral approaches.

- Sub-national clusters can be effective in coordinating a response. As witnessed by the response to Cyclone Viyaru in May 2013 where DNO preparedness activities built the foundation for the coordinated response.

- Partnerships with academic institutions and government bodies can have great benefits in terms of designing and conducting assessments, developing training materials and capacity-building.

Moving forward

Nutrition coordination in Bangladesh is in transition. A deliberate effort is being made to transform the nutrition architecture at country-level to ensure that coordination forums adequately support the Government to strengthen routine nutrition programming. The goal is to establish coordination forums that address routine development programming, preparedness and emergency response. It is envisaged that one coordination forum led by the IPHN and co-led by UNICEF will be set up at national level with a mandate to support nutrition programming. A key focus of this new forum will be increased advocacy for preparedness. Sub-working groups within this forum will address various nutrition issues, such as NiE (currently the NC); Capacity and Learning (currently the Nutrition Working Group); IYCF (currently the IYCF Alliance); and Information Management (currently the Information Management Group). Discussions with the Government and multiple partners are underway to agree on roles and responsibilities in a new structure. The new architecture is expected to be in place effectively by the end of 2016 or early 2017.

For more information, contact: Andrew Sammy

References

1 The cluster works under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare as the technical ministry; however actual disaster preparedness and response falls under the Department of Disaster Management (DDM). The clusters usually come under the DDM umbrella as part of the humanitarian coordination task team (HCTT).

Also see: Global Nutrition Cluster knowledge management: process, learning