Enabling low-literacy community health workers to treat uncomplicated SAM as part of community case management: innovation and field tests

By Casie Tesfai, Bethany Marron, Anna Kim and Irene Makura .jpg?w=110)

Casie Tesfai is a Nutrition Technical Advisor at the International Rescue Committee in New York, where she provides global technical support to IRC’s nutrition programmes and leads work on the integration of nutrition into integrated community case management (iCCM).

Bethany Marron is a Nutrition Specialist at the International Rescue Committee in New York, where she provides technical programme and research support to IRC’s nutrition programmes worldwide.

Anna Kim is a Communications Officer at the International Rescue Committee in New York, where she supports the communications and advocacy work of the health unit.

Irene Makura is the Nutrition Coordinator at the International Rescue Committee in South Sudan, where she provides technical support to IRC’s emergency and recovery nutrition programmes. She has experience in Zimbabwe, Nigeria and South Sudan.

The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable contribution of the following individuals and donor in this process: IRC South Sudan: Stephen Epiu, Stanley Anyigu, David Maluak Kuol, James Kon Kon, John Akuei Deng, Santino Anyuon Arop, Fatuma Ajwang, Katja Ericson, Kimberly Bennett, Flavia Aber and all of the CHWs who gave so much of their time and dedication; IRC Mali: Marie Biotteau, Goita Ousmane, Ibrahima Siby, Mohamed El Moctar; IRC Niger: Pierrot Kalubi Balonda, Jacques Maurice Ousmane; IRC Chad: Franck Ntalaja Mpoyi, Philomene Ndeortolna; IRC New York: Hannah Taylor, Yolanda Barbera Lainez, Austin Riggs; Quicksand: Amey Bansod, Kevin Shane, Avinash Kumar, Ayush Chauhan; Brixton Health: Mark Myatt. This project was funded with UK aid from the UK government.

Location: South Sudan

What we know: Coverage and access to acute malnutrition treatment services remains inadequate. Experiences from iCCM show that, with support, low-literate community health workers (CHWs) can manage pneumonia, malaria and diarrhea.

What this articles adds: The International Rescue Committee (IRC) is developing and piloting tools to enable low-literacy CHWs to treat severe acute malnutrition (SAM) without complications. This has involved simplification (e.g. only MUAC used for admission and to monitor progress); innovation (e.g. visual materials developed by a specialist design agency); alignment with iCCM protocols (e.g. triage, anti-malarial protocols, symbols for gender and referral); and field tests, most recently in South Sudan. Key low-literacy challenges have been how to simplify the SAM treatment protocol; how to enable admission, follow-up, discharge, correct RUTF dosage and monitor treatment; and how to identify individual children on return. The tools have been well-received by CHWs. A final field test will inform a finalised toolkit. Collaboration with other agencies interested in piloting is welcome. A feasibility acceptability trial in 2016 and a randomised control trial of SAM (iCCM v CMAM (Community-Based Management of Acute Malnutrition) approach) is planned for 2017.

Low access and coverage for the treatment of acute malnutrition has been as persistent and perplexing as it is unacceptable. The main barriers of distance and high opportunity costs mean that a new approach to transform hard-to-reach services is most needed. (Puett, Hauenstein Swan & Guerrero, 2013). The child health community, through the integrated community case management (iCCM) of childhood illnesses strategy, has improved access to treatment for pneumonia, diarrhea and malaria by enabling the provision of treatment outside traditional health facilities through a large network of community health workers (CHWs) (Bryce, Friberg, Kraushaar et al, 2010; Schellenberg, Victora, Mushi et al, 2003; Victoria, Wagstaff, Schellenberg et al, 2003). Similarly, since 2014, the International Rescue Committee (IRC) has been exploring a treatment algorithm and tools that would empower low-literate providers to bring treatment for severe acute malnutrition (SAM) without complications directly to the villages of malnourished children. Our journey has included countless patient registers, dozens of modified mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) tapes, and partnerships with CHWs, designers, and experts in nutrition and iCCM. A year later, we have the results of the third and most recent field test in South Sudan. The IRC believes providing treatment for acute malnutrition outside the facility is possible, but understands that we have a lot to learn about what works.

Strong evidence demonstrates that low-literate CHWs can identify and correctly treat most children who have pneumonia, malaria and diarrhea when they are trained on simplified guidelines, supported with supervision, and provided with an uninterrupted supply of medicines (George, Menotti, Rivera et al, 2009; Yeboah-Antwi, Pilingana, Macleod et al, 2010). Some adaptations that have been introduced do not require literacy or numeracy. For example, to assess fast breathing, CHWs count chest in-drawing using colour-coded beads and timers to identify pneumonia and treat it with colour-coded drug packets of amoxicillin designated for infants or toddlers.

We want to extend these successes to nutrition by enabling low-literacy CHWs to treat SAM without complications. While the potential is vast, there are no examples of such integration that both adhere to the globally accepted guidelines for the treatment of SAM (including collection of performance indicators) and do so through low-literate CHWs (often because of literacy and numeracy requirements). The IRC believes that the integration of SAM without complications into iCCM, like iCCM, requires simplifications of the treatment algorithm and development of tools for low-literacy providers.

The IRC has been developing and field-testing these low-literacy tool prototypes in Mali, Chad, South Sudan and India since 2015. Recently in 2016, the IRC completed the third field test in South Sudan. During that field test, the IRC nutrition and iCCM teams, along with Quicksand (a human-centered design firm that supported IRC in the design and development of prototypes and field-testing with end-users), worked with 30 female, low-literate iCCM CHWs of varying ages and experience from Aweil South County, Northern Barh El Gazal state (iCCM CHWs in South Sudan are known as Community Based Distributors. In IRC’s iCCM programme, there is one CHW per 50 households. In Aweil South, IRC supports a network of over 600 CHWs. There is one CHW monitor per 15 CHWs who provides routine supervision, drug restocking and is in charge of monthly reporting.) The process focused on capturing the end-user’s perspective. Each group of CHWs was trained on each of the prototypes and participated in three rounds. During each round, they practiced using the tools and were observed by the IRC and Quicksand team. At the end of each round, CHW feedback was solicited on ease of use of the tools. For two rounds, CHWs worked with children enrolled in the outpatient therapeutic programme. Based on feedback from each round of CHW testing, revisions were made to the tools and applied in the subsequent rounds of testing. This process was repeated until the end of the field test.

This article outlines the key questions and answers that have emerged while developing low-literacy tools, the prototypes that were developed and field-tested, and the results of the third and most recent field test in South Sudan.

I. How can the SAM-treatment algorithm be simplified for administration by CHWs outside the health facility?

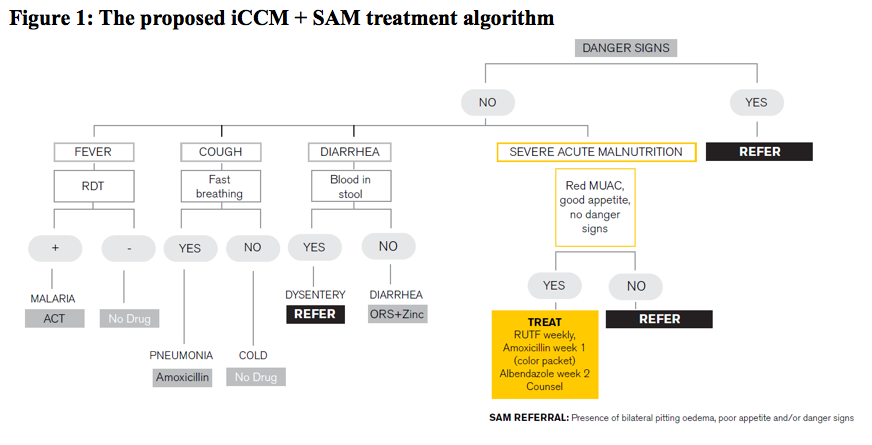

There are several areas where iCCM treatment overlaps with SAM treatment without complications, as shown in Figure 1. As part of the iCCM protocol, CHWs are already trained on how to take MUAC and check for bilateral pitting oedema. They also routinely check for ‘danger signs,’ which are very similar to the SAM protocol assessment for medical complications.

In the assessment phase, the appetite test will be the only new introduction for CHWs in the iCCM programme. Due to low-literacy, this will be a MUAC-only programme; weight and height will not be introduced for admission purposes. For admission, we propose that a red MUAC (<11.5cm) with no danger signs and a good appetite will be treated by the CHW. Follow-up will be continued by MUAC and discharge will be by attaining green MUAC (>12.5 cm), which is in line with global recommendations. For now, oedema will be considered a danger sign and CHWs will refer. CHWs will also immediately refer any child with a MUAC below 9.0 cm as a critical case. The only drug that will be introduced is albendazol, since CHWs are trained and equipped with amoxicillin and anti-malarials. CHWs will also be trained on how to give ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) using a dosage scale described below.

II. What tool can enable SAM treatment admission, follow-up and discharge by low-literate CHWs?

A study by Binns, Dale and Hoq et al demonstrated that changes in weight and MUAC occur similarly over the continuum of treatment and particularly during illness, introducing the possibility that MUAC could be used to follow-up children as an alternative to weight. (Binns, Dale, Hoq et al, 2015). The authors also concluded that further research would be necessary to develop additional tools that enable monitoring of children undergoing SAM treatment by MUAC as the sole anthropometric measure. Our work aimed to develop such a tool as well as tackle the challenge of low-literacy, which increases the difficulty of monitoring admission, follow-up and discharge as well as MUAC progression or regression during follow-up.

Process

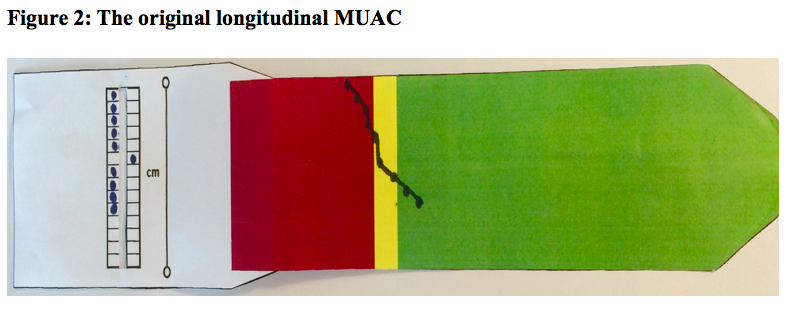

Initially, we developed a wide longitudinal MUAC that could be used throughout treatment, a concept based on early work on the MUAC tape from Alfred Zerfas (Zerfas, 1975). Every week, CHWs would mark the tape and connect the dots, as shown in Figure 2. One MUAC tape would be assigned to one child. A box was added with two columns to track visits (left) and absences (right) in order to determine defaulting. Several prototypes of this were developed and field-tested, but it was found to be too difficult for CHWs to connect dots and interpret the direction of the line. Also, the tape was too wide to find the mid-point of the upper arm and we faced cost issues; it was going to be difficult and expensive to find a supplier to cut these new, durable tapes, which also required special pens for marking.

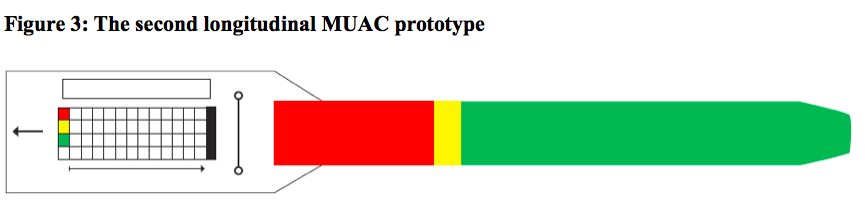

We reverted to the standard MUAC tape size for our second prototype by creating a colour-coded follow-up box where CHWs could place a dot in the corresponding weekly MUAC reading (absences would be inserted in the bottom row), as shown in Figure 3. This, too, was difficult to print and write on, so the follow-up box was moved onto a patient register with the goal of eliminating individualised MUAC tapes and creating one register sheet per child to track follow-up.

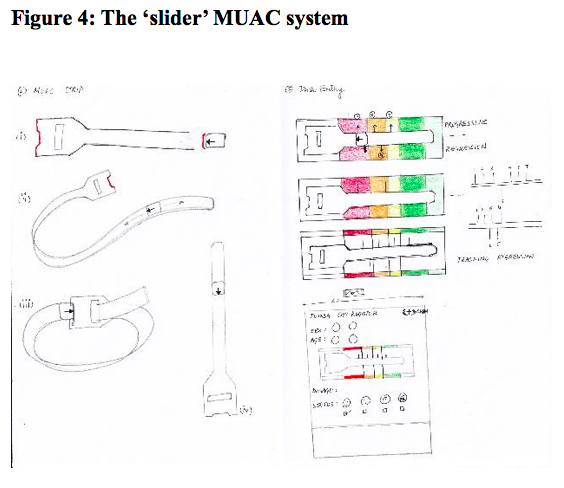

Another MUAC prototype was developed that used a ‘slider’ to hold the measurement spot on the MUAC tape after enclosing a child’s upper arm, as shown in Figure 4. The tape and slider would then be placed in an outline of the MUAC on the paper register. A line was drawn where the slider had been and then examined for which colour zone it fell into, as shown in photo 2. While slightly complicated, the design allowed CHWs to determine the direction (improvement, stationary or deterioration) of the MUAC measurement with the same plotting and visual interpretation technique as the preceding prototypes.

Solution

Solution

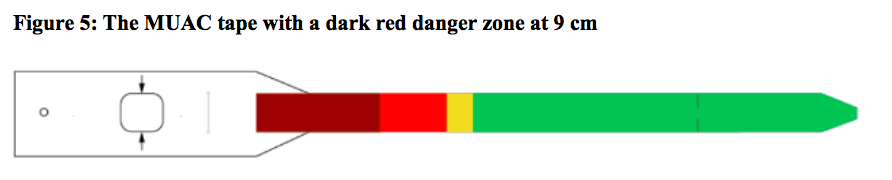

All of these prototypes proved too difficult and confusing for low-literate CHWs, which led to our most recent prototype, as shown in photo 3. We reverted back to a standard MUAC tape and added a new dark red zone, modeled after the dark red shade that signals a danger sign for iCCM in South Sudan. Since most of our programme data shows that most children with a MUAC less than 9 cm are also referred to the Stablisation Centre, we felt that this change to the tool and algorithm would ease the decision-making burden of the CHW for these critical cases. Since CHWs are already trained to take MUAC for referral, they had no problem doing so correctly. Across the board, CHWs preferred the inclusion of dark red, finding it easy to remember as a ‘danger sign’ requiring referral. Of the 30 CHWs, no one incorrectly reported the wrong colour when they took the MUAC and no one reported any difficulty telling the difference between the two red zones or remembering that dark red was a danger sign.

What we still don’t know

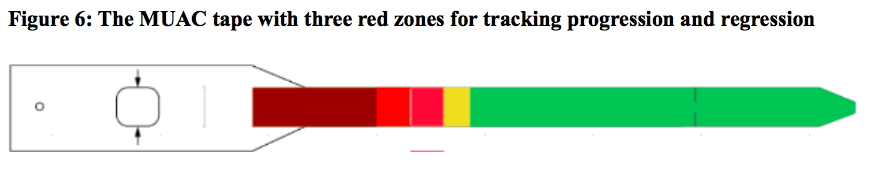

We are still confronting the issue of following up progression and regression. For example, it could be difficult to determine if a child is stationary, improving or deteriorating when recording the colour red for multiple consecutive weeks. The protocol requires an investigation after three consecutive visits without improvement. Since we found the danger-zone MUAC tape was perfectly feasible with two shades of red, we are exploring another prototype with a third red zone, as shown in Figure 6. Dark red would be less than 9 cm, standard red would be from 9 to 10.5 cm and another lighter red would be from 10.5 to 11.4 cm. This would mean a CHW could observe progression by moving from standard red to light red. However, this does not completely solve the problem, so more work is necessary.

III. How will low-literate CHW providers determine the correct dosage of RUTF?

III. How will low-literate CHW providers determine the correct dosage of RUTF?

Process

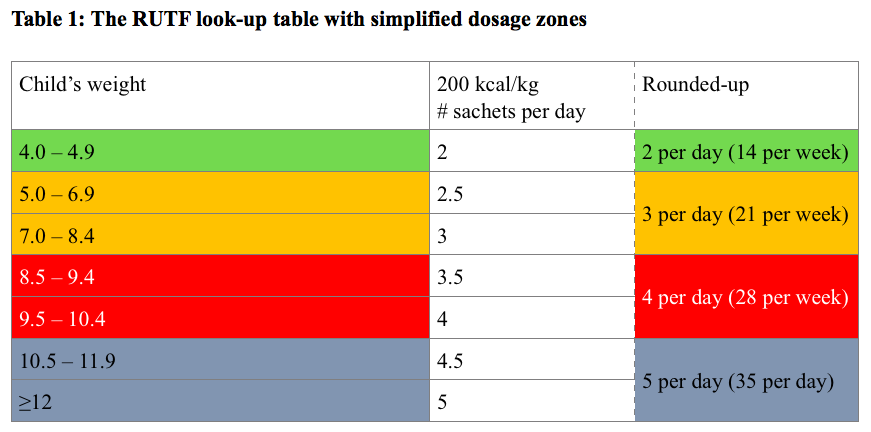

Determining daily dosage. In order to ensure CHWs could easily determine the correct dosage of RUTF each week, we first simplified the standard RUTF look-up table. For the look-up table, we rounded up where there were half sachets to create fewer dosage ‘zones’, as shown in Table 1 below. Next, we developed a corresponding colour-coded scale with shapes to represent a daily dosage derived from the simplified RUTF look-up table. Using the standard Salter scale, we created a decal to designate each dosage zone. When a child was weighed, the scale needle would fall into a colour and shape zone wherein CHWs could visualise the shapes as the daily dosage. Since Salter scales are widely used and available in nutrition programming, the card was developed to fit inside the plastic cover (there are two screw holes on the card where it is fastened in place).?

Calculating weekly dosage. The next issue we aimed to address was how to ensure CHWs correctly calculated the weekly dosage of RUTF. Initially, the IRC nutrition programme staff developed a prototype of a piece of local cloth with seven squares, so that after determining the daily dosage from the scale, the CHW could make seven piles of whatever quantity s/he determined. Quicksand built on this idea and developed an RUTF bag with seven pockets (called the RUTF StorCal) which enabled CHWs to calculate the correct weekly quantity (shown in action in photo 6). This may also help caretakers remember the daily dosage for their child. If programme resources allow, this presumably could be taken home and used there. Each pocket is designed to fit up to five sachets of RUTF and seals with Velcro. There is also a plastic window where the patient card can be inserted.

Calculating weekly dosage. The next issue we aimed to address was how to ensure CHWs correctly calculated the weekly dosage of RUTF. Initially, the IRC nutrition programme staff developed a prototype of a piece of local cloth with seven squares, so that after determining the daily dosage from the scale, the CHW could make seven piles of whatever quantity s/he determined. Quicksand built on this idea and developed an RUTF bag with seven pockets (called the RUTF StorCal) which enabled CHWs to calculate the correct weekly quantity (shown in action in photo 6). This may also help caretakers remember the daily dosage for their child. If programme resources allow, this presumably could be taken home and used there. Each pocket is designed to fit up to five sachets of RUTF and seals with Velcro. There is also a plastic window where the patient card can be inserted.

Solution

Solution

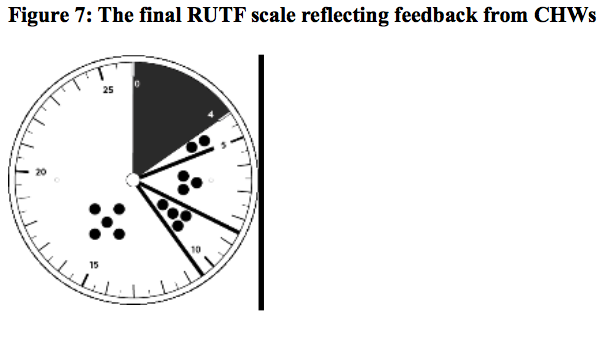

Field tests showed that using colour on the RUTF scale did not add value since CHWs relied only on counting the shapes. Previous field tests revealed that the scale with the least amount of detail was easiest to understand, as shown in photo 5, which was also field-tested in South Sudan. Both the updated RUTF scale and StorCal were met mostly with applause from CHWs in each of the field sites when these were presented, and very few mistakes were made.

Initially, there were a few occasions where CHWs were unsure of the daily quantity when the needle fell on the line between two zones. After being trained to round up, they made few mistakes.

Initially, there were a few occasions where CHWs were unsure of the daily quantity when the needle fell on the line between two zones. After being trained to round up, they made few mistakes.

The only other mistake that a few CHWs made concerned the ‘five’ zone. Since the cluster of dots was around 20kg, when the needle fell anywhere before that, as shown in photo 11, some CHWs said “four”, since the needle fell close to the four zone and did not reach the cluster of five dots.

During the feedback session, some CHWs said the lines were not dark enough, but that they could understand that everything between the lines was for that quantity. Since most children do not exceed 15kg, we decided to test a version with the cluster of five dots around 15kg and with bolder lines, as shown in Figure 7. After being trained on the changes, CHWs were able to correctly identify the daily quantity of children who fell in the ‘five’ zone at all different weights. We also discussed blacking out the 0-4 kg zone, since the national protocol in South Sudan requires any child less than 4 kg to be referred. For the StorCal, the only change suggested by CHWs was to add longer strips of Velcro for each pocket; they were afraid the RUTF might fall out.

IV. How will low-literate CHWs monitor treatment from admission to discharge?

IV. How will low-literate CHWs monitor treatment from admission to discharge?

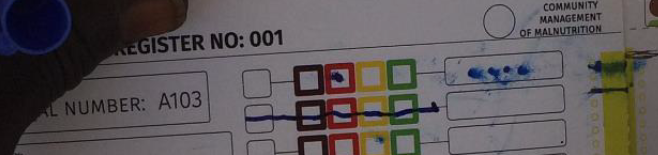

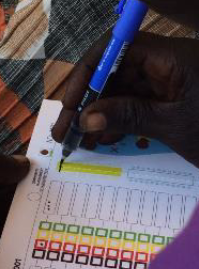

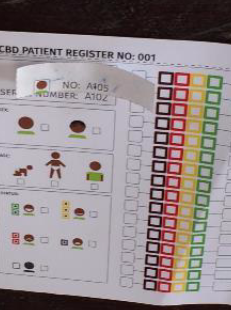

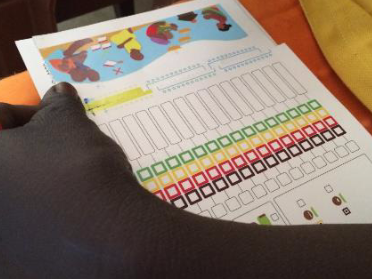

The patient register needed to be able to: 1) track a patient’s progression/regression over time; 2) log the course of treatment provided; 3) include a calculation of performance indicators; and 4) provide a method of providing a connection between the patient and the record for that patient, since CHWs may not be able to write the name of the child. The register was by far the most challenging tool. It underwent significant revisions and retesting based on CHWs’ difficulties using it and suggestions for improving it. Rigorous testing allowed us to develop appropriate icons and formats to document the sex and age of the child, their weekly status (including whether they defaulted or were non-respondent), and whether they were discharged as cured or died.

Process

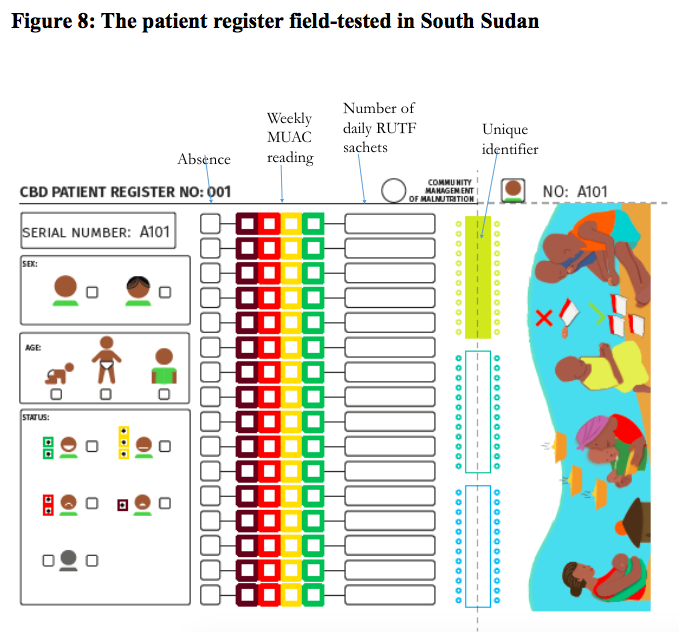

Figure 8 shows the first version that was tested in South Sudan. The register will be explained below by each section: sex and age, weekly follow-up (MUAC/RUTF), discharge status and the counterfoil ID system.

Sex and age: The icons to show sex were not well understood since they lacked facial features and did not have attributes of a girl or boy. CHWs were not able to immediately tell the difference between a boy and girl and felt they resembled other things, such as a cow or a house.

For age, we initially included three categories for infants (6-11 months), toddlers (12-23 months) and children (24-59 months). These were very confusing and the ages associated with each icon as reported by CHWs varied widely. Some thought the icons did not look like children at all. To align with iCCM, we then decided to include only two age categories: infant (6-11 months) and toddler (12-59 months).

CHWs also suggested that we incorporate sex and age icons from the iCCM register, since CHWs were already trained to recognise these. When we used the sex and age icons from the iCCM register, CHWs were able to easily recognise the difference between boys and girls and infants and toddlers.

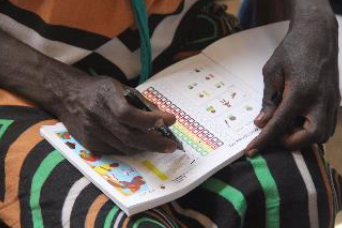

Weekly follow-up: CHWs had relatively few problems entering the colour of the MUAC every week and the number of RUTF sachets given, as shown in the photo below. Some CHWs forgot to enter each new MUAC reading on a new line, so this will need to be addressed in training. They improved the more they practiced.

Weekly follow-up: CHWs had relatively few problems entering the colour of the MUAC every week and the number of RUTF sachets given, as shown in the photo below. Some CHWs forgot to enter each new MUAC reading on a new line, so this will need to be addressed in training. They improved the more they practiced.

To remind CHWs to drop to the next line if a child is absent, they were asked to strike a line through the entire row, as shown in photo 14. This helped them to remember to start on a new line in the case of patient absence.

In testing revisions that might improve the quality of reporting, we found that CHWs preferred a picture of the MUAC tape at the top of the weekly follow-up and a photo of a sachet of RUTF above the dosage column. CHWs also preferred filling in circles for RUTF rather than a rectangle.

In testing revisions that might improve the quality of reporting, we found that CHWs preferred a picture of the MUAC tape at the top of the weekly follow-up and a photo of a sachet of RUTF above the dosage column. CHWs also preferred filling in circles for RUTF rather than a rectangle.

To remind CHWs that they would give amoxicillin on week one and albendazole (according to the South Sudan national protocol) on week two, we added an image of the drugs at weeks one and two. Those images were also added below the infant and toddler icons to remind them of the dosage according to age. The icons used for albendazole still need to be tested with CHWs.

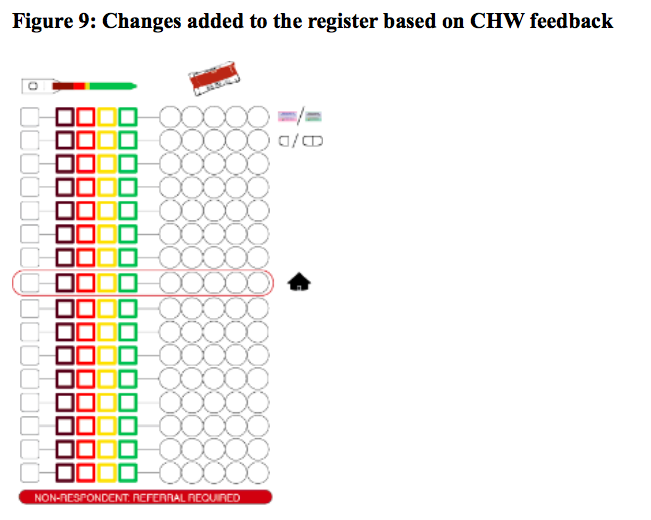

Since an appropriate length of stay for recovery is less than eight weeks, the IRC team decided to add a reminder at eight weeks so that a child remaining in red could be investigated. The CHW monitor will need to be involved in children who are not recovering well and help decide the course of action. We also added a bar after 16 weeks as a reminder of the non-respondent criteria. These changes are shown in Figure 9.

Discharge status (performance indicators)

Discharge status (performance indicators)

The discharge status icons underwent several iterations. It required five icons: recovery, death, defaulting, non-response and transfer. Like the age and sex icons, CHWs reported that the icons lacked facial features. Some CHWs asked how a person could not have a neck and shoulders. Because Quicksand designers were in the field with us, we were able to continually mock up and test alternative icons until we felt confident that they were widely understood by CHWs.

Recovery. CHWs preferred a smiling child with facial features, as shown on the right-hand in the image below. The final recovery icon preferred by CHWs was a smiling child with two green dots (since the criteria for recovery is two consecutive visits >12.5 cm).

Mortality. The icon for mortality proved to be the most challenging, since mortality is a sensitive issue. Based on suggestions from CHWs, we tested a coffin, a cross, a coffin with a cross, a tearful mother and a deceased person covered with a cloth. One CHW told us: “These are really sad. Why does it have to be a person? If I saw something like a dead bird, I wouldn’t feel sad, but I would know that it means death.” We then created a ‘dead bird’ icon and tested it with CHWs, as shown in photo 17.

Mortality. The icon for mortality proved to be the most challenging, since mortality is a sensitive issue. Based on suggestions from CHWs, we tested a coffin, a cross, a coffin with a cross, a tearful mother and a deceased person covered with a cloth. One CHW told us: “These are really sad. Why does it have to be a person? If I saw something like a dead bird, I wouldn’t feel sad, but I would know that it means death.” We then created a ‘dead bird’ icon and tested it with CHWs, as shown in photo 17.

The dead bird icon was preferred by many CHWs, who found it amusing rather than sad. Some CHWs did not immediately know what it was, but did not have a negative reaction when it was explained. We felt that most CHWs with training would remember that the dead bird icon represented mortality, and that it was most culturally appropriate.

The dead bird icon was preferred by many CHWs, who found it amusing rather than sad. Some CHWs did not immediately know what it was, but did not have a negative reaction when it was explained. We felt that most CHWs with training would remember that the dead bird icon represented mortality, and that it was most culturally appropriate.

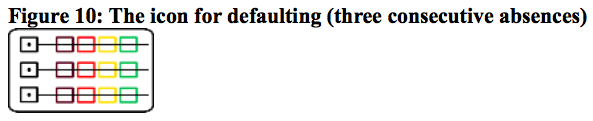

Defaulting. Defaulting, according to the national protocol in South Sudan, is comprised of three consecutive absences. This icon was developed to show three consecutive absences with lines drawn through the rows. Drawing the line all the way through the row tended to remind CHWs of that. CHWs did not seem to have difficulties with this icon and preferred the image shown in Figure 10.

Non-Respondent. The icon for non-respondent was also slightly difficult. Since non-respondent is essentially a child who doesn’t recover, we created a ‘sad child.’ CHWs suggested that we make the child look more malnourished so they could remember this child is still malnourished and hasn’t yet recovered.

Non-Respondent. The icon for non-respondent was also slightly difficult. Since non-respondent is essentially a child who doesn’t recover, we created a ‘sad child.’ CHWs suggested that we make the child look more malnourished so they could remember this child is still malnourished and hasn’t yet recovered.

Transfer. The icon for transfer was initially a very simple health facility; however CHWs did not easily recognise it. They suggested that we use the iCCM referral icon as shown in Figure 11. Although we initially felt it was too detailed and difficult to see at small size, all CHWs preferred the iCCM icon since they were already trained on it and understood it. We therefore incorporated the icon from the iCCM register for referral.

What we still don’t know

The register will continue to be a work in progress, particularly as we explore more options to track progression and regression. We will continue to field test and make revisions based on CHW feedback.

The register will continue to be a work in progress, particularly as we explore more options to track progression and regression. We will continue to field test and make revisions based on CHW feedback.

V. How does a CHW identify a child for follow-up if the CHW cannot write the child’s name?

We recognised the need to enable a CHW who cannot read or write to link record and child correctly. To address this problem, Quicksand developed a counterfoil ID system. This system would provide a unique identifier on each patient register sheet and the patient card (an earlier prototype is shown in photo 18). When the patient card is torn off and given to the caretaker, she would return with this card and the CHW would be able to match it to the correct record in the register.

Process

Process

Several prototypes were developed and tested. The system field-tested in South Sudan required the CHW to draw a line through two circles in a coloured box and then match up the coloured boxes and the line, as shown in photo 19 below. There were 12 rows of circles per box and three colour options, which meant 36 pages per register.

We also tested a redundant ID system of matching an alphanumeric code with the register in case CHWs lost their card. This small alphanumeric code could be kept in the plastic window of the StorCal to serve as a back-up identification system if the patient card gets lost. It was clear early on that CHWs were unable to match the alphanumeric code with precision.

CHWs also struggled with matching the counterfoil. Some CHWs forgot to drop down to the next line for each subsequent page. Instead, they drew the line in the same location on each page. Because the alphanumeric code was torn off the patient card, this also resulted in uneven pages that confused CHWs when trying to match the counterfoil, as shown in photo 22. They tended to match the lines, but not the boxes.

CHWs also struggled with matching the counterfoil. Some CHWs forgot to drop down to the next line for each subsequent page. Instead, they drew the line in the same location on each page. Because the alphanumeric code was torn off the patient card, this also resulted in uneven pages that confused CHWs when trying to match the counterfoil, as shown in photo 22. They tended to match the lines, but not the boxes.

It was decided that the alphanumeric ID system was probably unnecessary and only made the system more complex. The IRC team therefore decided that we would omit the alphanumeric ID system but would place the patient card inside the plastic window of the StorCal to try to prevent it from being lost.

It was decided that the alphanumeric ID system was probably unnecessary and only made the system more complex. The IRC team therefore decided that we would omit the alphanumeric ID system but would place the patient card inside the plastic window of the StorCal to try to prevent it from being lost.

Solution

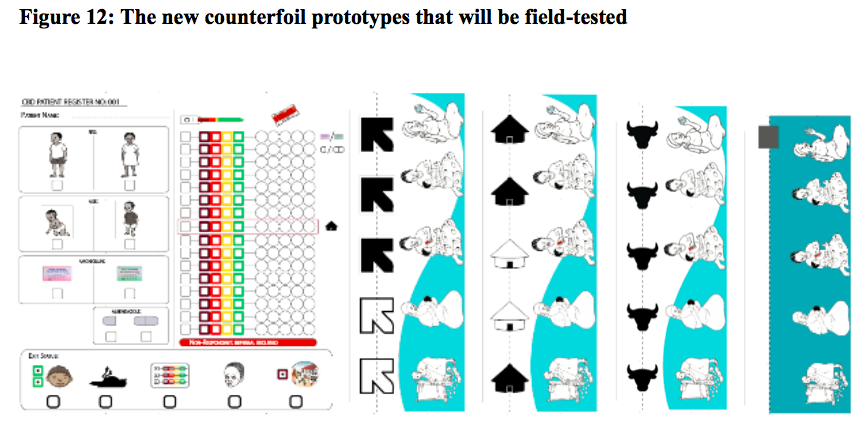

In order to develop an easier system for the counterfoil, we tested the ability of CHWs to match shapes familiar to them, like cows, mud huts and the IRC logo. We tested black and white images of each icon with three to five different permutations; more permutations would allow for more register pages. To test the ease of matching shapes, each CHW was given half and chose her match among other pieces, as shown in photo 23. Overall, this system proved much more feasible. Some CHWs made a few mistakes initially. Once they were told to match both the shapes and the colours, very few made any errors. CHWs unanimously preferred the new counterfoil system.

Key messages were also added to the patient card to serve as a job aid for the CHW to explain how to give RUTF to the caretaker. These icons were tested and revised based on CHWs’ ease of understanding. Like the age and sex icons, they were aligned with images CHWs have already been trained to recognise.

Key messages were also added to the patient card to serve as a job aid for the CHW to explain how to give RUTF to the caretaker. These icons were tested and revised based on CHWs’ ease of understanding. Like the age and sex icons, they were aligned with images CHWs have already been trained to recognise.

What we still don’t know

The only drawback of using shapes as opposed to different coloured boxes as placeholders is increased difficulty of knowing where to turn to in the register. Quicksand is currently exploring whether it is possible to combine coloured placeholders with shapes. A fourth option of having only coloured boxes that gradually get bigger (then change colour) is a potential solution (see Figure 12, right-hand side).

These new counterfoils will need to be field-tested again once printed up in the register to determine which system is most feasible for CHWs. We also may need to explore an alternative option in case the caretaker loses the patient card.

These new counterfoils will need to be field-tested again once printed up in the register to determine which system is most feasible for CHWs. We also may need to explore an alternative option in case the caretaker loses the patient card.

Reflections and next steps

If asked whether low-literate CHWs could treat severe malnutrition two years ago, we may have thought that low-level providers might operate a poorly run programme, given the complexities of the CMAM protocol.

If asked whether low-literate CHWs could treat severe malnutrition two years ago, we may have thought that low-level providers might operate a poorly run programme, given the complexities of the CMAM protocol.

Ask us that question today and we immediately recall the faces of the eager, invested and excited CHWs that joined our efforts. We remember the small, continual victories advanced by an unlikely team of colleagues committed to the same goal, from nutrition experts to iCCM experts, CHWs and designers, and we remember those who encouraged us to keep going. Mostly, we feel proud that we’ve come this far and can say with confidence that this is very possible.

But the work is far from over.

Our plan is to conduct another round of field-testing so that we can make final decisions on the toolkit. We want to start collaborating with other agencies who are interested in piloting the tools and informing the revisions. In 2016, we hope to conduct a feasibility and acceptability trial to determine how well CHWs use these tools to treat SAM children without complications. We hope to be able to conduct a randomised controlled trial on the impact (quality, coverage, cost-efficiency) of SAM treatment as part of iCCM compared to the standard of care (CMAM) in 2017.

Our plan is to conduct another round of field-testing so that we can make final decisions on the toolkit. We want to start collaborating with other agencies who are interested in piloting the tools and informing the revisions. In 2016, we hope to conduct a feasibility and acceptability trial to determine how well CHWs use these tools to treat SAM children without complications. We hope to be able to conduct a randomised controlled trial on the impact (quality, coverage, cost-efficiency) of SAM treatment as part of iCCM compared to the standard of care (CMAM) in 2017.

In the nutrition community we have long known that access and coverage must change. Increasingly, everyone has recognised that scaling up more of the same will not work. We believe this is one way to start scaling differently. The potential implications of applying a truly community-based model to malnutrition are enormous. Thousands of children could get access to life-saving treatment without leaving home. We have an opportunity to improve the survival, health and development for an entire generation. This doesn’t mean we are not aware of the numerous challenges that still require solutions, but it’s hard not to be inspired when we think about the immediate response of the very CHWs who perhaps understood better than any of us the potential implications of this work: “When can we start?”

In the nutrition community we have long known that access and coverage must change. Increasingly, everyone has recognised that scaling up more of the same will not work. We believe this is one way to start scaling differently. The potential implications of applying a truly community-based model to malnutrition are enormous. Thousands of children could get access to life-saving treatment without leaving home. We have an opportunity to improve the survival, health and development for an entire generation. This doesn’t mean we are not aware of the numerous challenges that still require solutions, but it’s hard not to be inspired when we think about the immediate response of the very CHWs who perhaps understood better than any of us the potential implications of this work: “When can we start?”

For more information, contact: Casie Tesfai

References

Binns P, Dale N, Hoq M, Banda C, Myatt M. Relationship between mid upper arm circumference and weight changes in children 6-59 months. Archives of Public Health (2015) 73: p 54.

Bryce J, Friberg IK, Kraushaar D, Nsona H, Afenyadu GY, Nare N, Kyei-Faried S, Walker N, 2010. LiST as a catalyst in program planning: experiences from Burkino Faso, Ghana, and Malawi. Int J Epidemiol 39: pp i40-i47.

George A, Menotti EP, Rivera D, Montes I, Reyes CM, Marsh DR, 2009. Community case management of childhood illness in Nicaragua: transforming health systems in underserved rural areas. J Health Care Poor Underserved 20: pp 99-115.

Puett C, Hauenstein Swan S, Guerrero, S (2013). Access for All, Volume 2: What factors influence access to community based treatment of severe acute malnutrition? (Coverage Monitoring Network, London, November 2013).

Schellenberg JA, Victora CG, Mushi A, de Savigny D, Schellenberg D, Mshinda H, Bryce J, 2003. Inequities among the very poor: health care for children in rural southern Tanzania. Lancet 361: pp 561-566.

Victoria CG, Wagstaff A, Schellenberg JA, Gwaitkin D, Claeson M, Habicht JP, 2003. Applying an equity lens to child health and mortality: more of the same is not enough. Lancet 362: pp 233-241.

Yeboah-Antwi K, Pilingana P, Macleod WB, Semrau K, Siazeele K, Kalesha P, Hamainza B, Seidenberg P, Mazimba A, Sabin L, Kamholz K, Thea DM, Hamer DH, 2010. Community case management of fever due to malaria and pneumonia in children under five in Zambia: a cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med 7 e1000340.

Zerfas, A. The insertion tape: a new circumference tape for use in nutritional assessment. Am J Clin Nutr 1975, 28 pp 782-787.