Review of the role of food and the food system in the transmission and spread of ebola virus

Summary of research1

Location: West Africa

What we know: The current outbreak of ebola virus disease (EVD) centred in West Africa is the largest in history. The full role of food in EVD spread is not well studied.

What this article adds: A recent literature review investigated how food may transmit ebola viruses and how the food system contributes to EVD outbreak and spread. Harvesting and consumption of ‘bushmeat’ is a high-risk activity; food insecurity may lead to more bush-meat harvesting and increase outbreak risk. There is evidence linking ebola to pigs; an outbreak amongst swine would have economic and potential outbreak implications. There is no published literature on the risk of plant food products transferring ebola virus; this would have implications for local and global food systems. Food and the food system may be more implicated in ebola virus transmission than expected; further research is urgently needed.

The current outbreak of ebola virus disease (EVD) centred in West Africa is the largest in history, with nearly ten times more individuals contracting the disease than all previous outbreaks combined. Active transmission was occurring in three countries (Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone), and seven additional countries experienced isolated cases. With food systems an integral part of a globalised world, this article investigates the connections that exist between EVD outbreaks and food, describes what is currently known about how food can transmit ebola viruses, and how the food system contributes to EVD outbreak and spread.

The details of human-to-human and zoonotic ebola virus transmission have justifiably received the largest share of research attention and much information exists on these topics. However, although food processing – in the form of slaughtering and preparing wildlife for consumption (referred to as bushmeat) – has been implicated in EVD outbreaks, the full role of food in EVD spread is poorly understood and has been little studied.

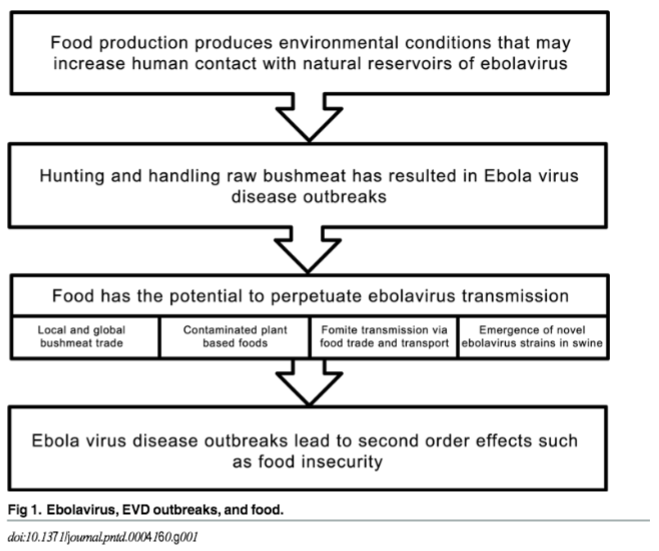

The authors conducted a literature review using keyword searches in online databases to assess the current state of knowledge regarding how food can or may transmit ebola viruses and how the food system contributes to EVD outbreak and spread. The authors categorised results of the search into various topics, outlined below. Figure 1 outlines the ways in which food is connected to EVD outbreaks.

Figure 1: Ebola virus, EVD outbreaks and food

Animal food products and ebola virus transmission

Bushmeat

Although the exact nature of animal-to-human transmission of ebola viruses is not often known, the harvesting of bushmeat (including rodents, bats, shrews, duikers and non-human primates) is directly related to ebola virus transmission. The hunting and butchering of bushmeat exposes humans to blood and other fluids of potentially infected animals. In 2014, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) noted that human ebola virus infections have been associated with handling and eating infected animals, with evidence of previous outbreaks of EVD beginning after humans handled infected carcasses of primates and duikers (Rouquet et al, 2005).

While bushmeat harvesting and consumption is a proven high-risk activity, it is an important source of cash income and a food source in West Africa, particularly during times of economic hardship (Leroy et al, 2009). The public health risk from zoonotic pathogens entering countries via infected bushmeat is estimated to be substantial due to widespread smuggling, including into the US and Europe, where demand is high, although exact figures and associated risk are very difficult to establish (European Food Safety Authority, 2014).

Livestock

It has been hypothesized that livestock could be a possible ebola virus reservoir, but studies to date on horses, sheep, goats, cattle and chickens have been inconclusive. There is, however, evidence linking ebola viruses and pigs, specifically the ‘Reston virus’ (an ebola virus not pathogenic to humans) (e.g. Pan et al, 2014). Recent studies have shown that swine can become infected with ebola virus, develop clinical symptoms and transmit the virus to healthy pigs (Kobinger et al, 2011). In 2012, Weingartl et al determined that infected pigs could transmit the virus to non-human primates. Additional studies in Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) have suggested that EVD outbreaks have occurred in areas with high densities of swine (Weingartl et al, 2013) or following large mortality events of swine (Katayi, 2014). If swine are contributing to EVD aetiology, it is a cause for concern in sub-Saharan Africa where swine production is growing, often in areas near to the habitat of bats, who are increasingly being identified as the key ebola virus reservoir (Olival & Hayman, 2014).

Plant food products and ebola virus transmission

Consumption of contaminated plant food products

There is concern that ebola virus may be transmitted to humans via bat saliva or faeces on fruit such as mangoes or guava. This mechanism has been experimentally verified for the Marburg virus (a member of the Filoviridae family with ebola viruses) (Amman et al, 2015) and the Nipah virus, whose reservoir is also in fruit bats (Luby et al, 2009). It is plausible, therefore, that this mode of transmission may either start or aid the spread of EVD during outbreaks, although the current lack of knowledge and data make it impossible to quantify the risk (European Food Safety Authority, 2014).

Fomite transmission involving plant food products

Fomite transmission (transmission of infectious disease by objects) of EVD is possible, although the risks during food harvesting and production are not well understood. There is no published literature on the risk of plant food products serving as fomites in ebola virus transmission, although other viruses are known to be transmitted via food contaminated by food preparers that can subsequently infect individuals after they consume or handle the food, such as hepatitis A (Boone & Gerba, 2007) and Lassa fever, which is closely related to EVD (WHO, 2015).

Fomite transmission depends on virus survival in the environment and studies have shown that the ebola virus is able to survive outside the host (especially at lower temperatures) between several days and over three weeks (Sagripanti et al, 2010). It should be noted that fomite transmission involving raw food products has not been documented and warrants further research.

Other ebola virus and food considerations

Pubic health consequences of landscape changes caused by food production

Food systems may indirectly contribute to EVD transmission, particularly the consequences of environmental conditions such as deforestation that lead to increased human interaction with wildlife species that carry ebola viruses (Muyembe-Tamfum et al, 2012). Experts have begun exploring the connections between the latest EVD outbreak and ecological disruptions, including those related to agriculture (Bausch & Schwarz, 2014).

Additional swine concerns

This article suggests that an EVD outbreak among farmed swine would pose a number of concerns, including: significant animal loss with severe economic consequences; fear and panic among consumers regarding EVD as a food-borne illness leading to severe market disruption; and the considerable risk of ebola virus becoming endemic in wild pigs, which are known to carry numerous human disease-causing pathogens already (Bevins et al, 2014). There is an additional concern that swine could potentially serve as sites for new, more harmful strains of the virus to arise (MacNeil & Rollin, 2012).

Harvest, transport and trade

If ebola viruses do remain infectious on fomites for several weeks in a real-world environment, there are implications for the global food system from harvest to the end-consumer which could have major implications for the economies and labour forces of affected nations. A scenario is described in the paper where potential transmission involves an enclosed, refrigerated shipping container on a cargo ship transporting food products and the possible routes of contamination.

Food insecurity in West Africa

The EVD outbreak in West Africa has led to increases in food insecurity in the three affected countries. The authors summarise a UN Food and Agriculture Organization report from September 2014 of severe disruptions in food availability due to: quarantine-imposed travel restrictions on sellers and consumers; panic buying; dramatic price increases; and reduced food production and harvests (including income from cash-cropping) caused by farm labour shortages and restrictions on movement. Increasing food insecurity could potentially lead to more bushmeat harvesting and associated risks of further outbreaks.

Conclusions and research needs

While much remains unknown about ebola virus transmission (Osterholm et al, 2015), this literature reveals surprising preliminary evidence that food and the food system may be more implicated in ebola virus transmission than expected. Further research is urgently needed.

References

1 Mann E, Streng S, Bergeron J, Kircher A, 2015. A Review of the Role of Food and the Food System in the Transmission and Spread of Ebolavirus. PLoS Neg lTrop Dis 9(12):e0004160. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004160

Amman BR, Jones ME, Sealy TK, Uebelhoer LS, Schuh AJ, Bird BH, et al. Oral shedding of Marburg virus in experimentally infected Egyptian fruit bats (Rousettus Aegyptiacus). J Wildl Dis. 2015; 51 (1):113–24. doi: 10.7589/2014-08-198 PMID:25375951 PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases | DOI:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004160 December 3, 2015 9 / 11

Bausch DG, Schwarz L. Outbreak of Ebola Virus Disease in Guinea: Where Ecology Meets Economy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014; 8: e3056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003056 PMID: 25079231 PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases | DOI:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004160 December 3, 2015 10 / 11

Bevins SN, Pedersen K, Lutman MW, Gidlewski T, Deliberto TJ. Consequences Associated with the Recent Range Expansion of Nonnative Feral Swine. BioScience. 2014; 64: 291–299. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biu015

Boone SA & Gerba CP. Significance of Fomites in the Spread of Respiratory and Enteric Viral Disease. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007; 73: 1687–1696. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02051-06 PMID: 17220247

Chaber A-L, Allebone-Webb S, Lignereux Y, Cunningham AA, Marcus Rowcliffe J. The scale of illegal meat importation from Africa to Europe via Paris. Conserv Lett. 2010; 3: 317-321. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-263X.2010.00121.x

European Food Safety Authority. An update on the risk of transmission of Ebola virus (EBOV) via the food chain Part 2. EFSA J. 2015; 13: 4042-4058. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2015.4042

Katayi, K. Ebola sleuths scour DR Congo jungle for source of outbreak (L’Agence France-Press). Yahoo News. 23 Oct 2014. Accessed 3 Aug 2015.

Kobinger GP, Leung A, Neufeld J, Richardson JS, Falzarano D, Smith G, et al. Replication, Pathogenicity, Shedding, and Transmission of Zaire ebolavirus in Pigs. J Infect Dis. 2011; 204(2):200-8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir077 PMID: 21571728

Leroy EM, Epelboin A, Mondonge V, Pourrut X, Gonzalez J-P, Muyembe-Tamfum J-J, et al. Human Ebola Outbreak Resulting from Direct Exposure to Fruit Bats in Luebo, Democratic Republic of Congo, 2007. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2009; 9: 723-728. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2008.0167 PMID: 19323614

Luby SP, Gurley ES, Hossain MJ. Transmission of human infection with Nipah virus. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2009; 49: 1743–1748. doi: 10.1086/647951

MacNeil A & Rollin PE. Ebola and Marburg Hemorrhagic Fevers: Neglected Tropical Diseases? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012; 6: e1546. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001546 PMID: 22761967

Muyembe-Tamfum JJ, Mulangu S, Masumu J, Kayembe JM, Kemp A, Paweska JT. Ebola virus outbreaks in Africa: past and present. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 2012; 79: 451. doi: 10.4102/ojvr.v79i2.451 PMID: 23327370

Olival KJ, Hayman DTS. Filoviruses in Bats: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. Viruses. 2014; 6: 1759–1788. doi: 10.3390/v6041759 PMID: 24747773

Osterholm MT, Moore KA, Kelley NS, Brosseau LM, Wong G, Murphy FA, et al. Transmission of Ebola Viruses: What We Know and What We Do Not Know. mBio. 2015; 6: e00137–15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00137-15 PMID: 25698835

Pan Y, Zhang W, Cui L, Hua X, Wang M, Zeng Q. Reston virus in domestic pigs in China. Arch Virol. 2014; 159: 1129–1132. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1477-6 PMID: 22996641

Rouquet P, Froment J-M, Bermejo M, Kilbourn A, KareshW, Reed P, et al. Wild animal mortality monitoring and human Ebola outbreaks, Gabon and Republic of Congo, 2001-2003. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005; 11: 283–290. doi: 10.3201/eid1102.040533 PMID: 15752448

Sagripanti J-L, Rom AM & Holland, LE. Persistence in darkness of virulent alphaviruses, Ebola virus, and Lassa virus deposited on solid surfaces. Arch Virol. 2010; 155: 2035–2039. doi: 10.1007/s00705-010-0791-0 PMID: 20842393

Weingartl HM, Embury-Hyatt C, Nfon C, Leung A, Smith G, Kobinger G. Transmission of Ebola virus from pigs to non-human primates. Sci Rep. 2012; 2: 811. doi: 10.1038/srep00811 PMID: 23155478

Weingartl HM, Nfon C, Kobinger G. Review of Ebola virus infections in domestic animals. Dev Biol Basel. 2013; 135: 211–218. doi: 10.1159/000178495 PMID: 23689899

WHO. Lassa fever. WHO [Internet]. 2015 [cited 23 Jul 2015].