Why invest and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices?

Summary of research1

Location: Global

What we know: Global breastfeeding rates remain far below international targets, commitment to breastfeeding in terms of policy and investment has waned.

What this article adds: A systematic review and meta-analyses was conducted to review determinants of breastfeeding and the effectiveness of interventions. Supportive measures are needed involving health systems and services, family and community, and workplace and employment. Best outcomes are achieved through adequate delivery of relevant interventions delivered concurrently through several channels. Women’s work is a leading motive for not breastfeeding or early weaning; the majority or women with little or no maternity protection (80%) live in Africa and Asia. Global infant formula sales in 2014 were worth US$44·8 billion; most of projected (50%) growth is in the Middle East, Africa and Asia-Pacific regions. Economic losses of not breastfeeding are estimated at $302 billion annually or 0·49% of world gross national income. Increased and continued exclusive breastfeeding translate into significantly reduced treatment costs of childhood disorders. The patterns, drivers and consequences of suboptimal breastfeeding, and the interventions needed, will vary by setting. Reliable estimates of the costs and benefits of the actions needed to support optimal breastfeeding, including maternity entitlements, are difficult to calculate; urgent research is needed. Six actions are proposed, related to advocacy, societal attitudes, political will, breastmilk substitute industry regulation, scale up of interventions, and removal of structural and societal barriers. Political support and financial investment are needed.

Global breastfeeding rates remain far below international targets and commitment to breastfeeding in terms of policy and investment is in a state of fatigue. Despite its established benefits, breastfeeding is no longer a norm in many communities. Paper 2 of the Lancet series on breastfeeding summarises a systematic review of available studies and revises previous conceptual frameworks to identify the determinants of breastfeeding. Case studies on three pairs of countries (Bangladesh/Nigeria. Brazil/China, USA/UK) that are similar in economic development but differ in breastfeeding trends were constructed to explore why breastfeeding prevalence has increased, stagnated, or declined with time. It also describes a systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions aimed at promoting, protecting and supporting breastfeeding.

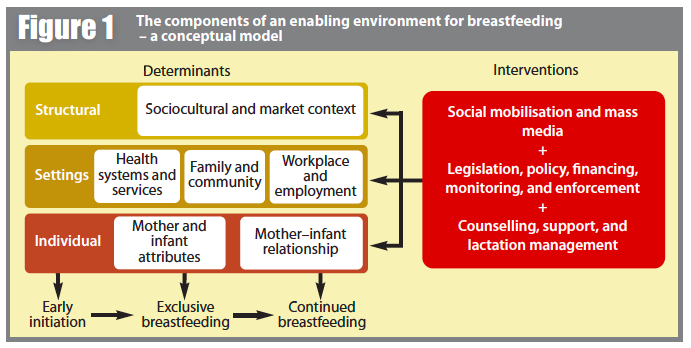

Multifactorial determinants of breastfeeding need supportive measures at many levels, from legal and policy directives to social attitudes and values, women’s work and employment conditions, and healthcare services to enable women to breastfeedThe authors examined the effects of interventions according to the three settings identified in the conceptual model (Figure 1): health systems and services, family and community, and workplace and employment. The meta-analyses showed that when relevant interventions are delivered adequately, breastfeeding practices are responsive and can improve rapidly. The best outcomes are achieved when interventions are implemented concurrently through several channels, e.g. combined health systems and community interventions can increase exclusive breastfeeding by 2·5 times

Women’s work is a leading motive for not breastfeeding or early weaning. Although nearly all countries have maternity protection legislation, only 98 (53%) of 185 countries meet the International Labour Organization’s 14-week minimal standard and only 42 (23%) meet or exceed the recommendation of 18 weeks’ leave; in addition, there are 32 large informal work sectors for which protection does not extend to. Consequently, hundreds of millions of working women have no or inadequate maternity protection, the overwhelming majority (80%) of whom live in Africa and Asia. Maternity leave and workplace interventions are beneficial, although studies are few and are generally limited to high income settings. Most studies reviewed explored the effects of direct interventions, rather than the role of policies and enabling interventions, such as maternity and workplace policies or health insurance for lactation support.

It is well understood that the marketing of breastmilk substitutes (BMS) negatively affects breastfeeding. The International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes (1981) and subsequent World Health Assembly resolutions (the Code) represent the collective will of the member states of the United Nations (UN) to protect, promote and support breastfeeding, and so carries substantial political and moral weight. However, its effectiveness depends on national legislation, monitoring and enforcement. Using market research, the authors describe the growing retail value of the baby milk formula industry; global sales in 2014 were US$44·8 billion, illustrating the industry’s large, competitive claim on infant feeding. Sales are projected to increase by more than 50% by 2019, with most of this growth in the Middle East, Africa and Asia-Pacific regions.

Using economic modelling techniques, the authors describe the effects of not breastfeeding being associated with lower intelligence and estimate economic losses of about $302 billion annually or 0·49% of world gross national income(GNI). Losses in low and middle income countries account for $70.9 billion (0.39% of GNI). The paper goes on to describe reduced treatment costs of five common infectious diseases for four countries (UK, USA2, Brazil and China) if exclusive breastfeeding and continued breastfeeding (up to 1 or 2 years depending on country and disorder) were to increase.. A 10% point increase in exclusive breastfeeding up to 6 months or continued breastfeeding up to 1 year or 2 years (depending on country and disorder) would translate into reduced treatment costs of childhood disorders of at least $312 million in the USA, $7·8 million in the UK, $30 million in urban China, and $1·8 million in Brazil. The environmental costs of BMS (energy to manufacture, materials for packaging, fuel for transport distribution and water fuel and cleaning agents for daily preparation and use) are also considered though not monetised, e.g. more than 4000 L of water are estimated to be needed along the production pathway to produce just 1 kg of BMS powder.

The review could not ascertain national or overseas aid budgets for the protection or support of breastfeeding; limited data suggests an overall decrease.

Discussion

The health and economic costs of suboptimal breastfeeding are largely unrecognised; the authors argue that investments to promote breastfeeding, in both rich and poor settings, need to be measured against the cost of not doing so. The world is still not a supportive and enabling environment for most women who want to breastfeed; achieving this is a collective societal responsibility.

Too few women are appropriately supported through adequate maternity and workplace entitlements to be able to work or attend school and still breastfeed; either they are not provided or the women are working in the informal economy. The patterns and drivers of suboptimal breastfeeding vary by setting. Therefore, the mixture of interventions and investments needed to implement them, including the cost of maternity entitlement, are likely to differ greatly between settings. Without more robust data, reliable estimates of the costs and benefits of the actions needed to support optimal breastfeeding are difficult to calculate. One study estimated that it will cost $17·5 billion globally for a large set of interventions, much of this figure driven by the recurring costs of maternity entitlements for poor women. Research into the costs of breastfeeding-enabling policies and programmes relative to their full range of benefits, including maternity entitlements, is urgently needed.

In low-income and middle-income countries, the improvement of breastfeeding impacts on preventable infant and child deaths. In both high-income and low-income countries, improvements in breastfeeding will improve human capital and help to prevent non-communicable diseases in women and children. Low-income and middle-income countries are at a crossroads of deciding whether to act to avoid the downward trends in breastfeeding practices that have been noted in high-income countries in the past century.

This review of the evidence and country case studies show that successful protection, promotion and support of breastfeeding need measures at many levels to realise the potential gains from increasing rates of exclusive and continued breastfeeding. The authors propose six action points for policy makers and programme managers to approach this challenge:

- disseminate the evidence of the value of breastfeeding as a powerful intervention for health and development that benefits children and women alike

- foster positive societal attitudes towards breastfeeding

- show greater political will to protect, promote and support breastfeeding

- regulate the BMS industry through more vigorous enforcement of the Code (which will require political commitment and greater investment to ensure implementation and accountability)

- scale up and monitor breastfeeding interventions and trends in breastfeeding practices

- political institutions should exercise their authority and remove structural and societal barriers that hinder women’s ability to breastfeed.

The authors conclude that without commitment and active investment by governments, donors and civil society, the promotion, protection and support for breastfeeding will remain inadequate and the outcome will be major losses and costs that will be borne by generations to come.

References

1 Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? (2016) Rollins, N. C., Bhandari, N., Hajeebhoy, N., Horton, S., Lutter, C. K., Martines, J. C., Piwoz, E. G., Richter, L. M., Victora, C. G. The Lancet Breastfeeding Series Group (2016)

2 For USA, asthma, leukaemia, type 1 diabetes, and childhood obesity were also included in the analyses.