Experiences of multi-sector programming in Malawi

By Felix Pensulo Phiri

Felix Pensulo Phiri is Director of Nutrition in the Department of Nutrition, HIV and AIDS, Ministry of Health, Malawi. He is responsible for providing nutrition multi-sector oversight function and coordination for the National Nutrition Response and is the SUN nutrition focal point in Malawi.

Thanks are extended to those interviewed in the course of developing this article, including: Violet Orchardson, USAID; Stacia Nordin, FAO; Mutinta Hambayi, Nancy Arbuto, Trust Mlambo, WFP; Molly Kumwenda, CRS; Benson Kazembe, UNICEF; Owen Nkhoma, University of Malawi; Tisungeni Zimpita, CSONA; Kondwani Mpeniuwawa, Department of Nutrition, HIV and AIDS; and Janet Guta, Ministry of Health.

Location: Malawi

What we know: Malawi has made strong progress in reducing stunting and other forms or malnutrition, despite challenges of frequent flooding and food insecurity related to climate change. Malawi joined the SUN Movement in 2011.

What this article adds: There is strong political will and commitment by leadership to address hunger and undernutrition: nutrition is a priority area in the national development agenda; there is a nutrition coordinating office; and multi-sector nutrition platforms at national, district and sub-district levels have been established. The National Multi-sector Nutrition Policy and Strategic Plan guides the national nutrition response. The National Nutrition Education and Communication Strategy (NECS) includes both nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive programming, the latter catalysed by the SUN Movement and involving multiple sectors in planning and district technical support. Strengths of the SUN/NECS programme include strong leadership at all levels; a clear, consistent (globally and within country) guideline for action; heightened nutrition profile through new district structures; due attention and openness to ongoing learning; alignment of the donor network to support coordinated resource mobilisation; and a well organised civil society network. Challenges relate to fragmented rollout and funding; monitoring and accountability; inadequate consideration of maternal nutrition; conflicted interests of partners; and limited participation of the private sector. Continued support of the District Nutrition Coordination Committees (DNCC) is required; a comprehensive evaluation of NECS rollout would greatly inform future activities.

Background

Malawi is one of the poorest countries in the world, currently ranked 174 out of 187 countries in the 2014 Human Development Index. Life expectancy at birth is estimated at 54.8 years, which is a reflection of persistently high rates of poverty and the severe effects of the HIV/AIDS crisis and other health issues. Additional problems include over-dependence on subsistence production and rain-fed maize production and consumption, which contributes to diets that lack diversity and are poor in micronutrient-rich foods. In recent years, Malawi has been experiencing the effects of climate change, which has led to food insecurity and contributes to widespread poverty among the population and persistently high rates of undernutrition.

Malawi is one of the poorest countries in the world, currently ranked 174 out of 187 countries in the 2014 Human Development Index. Life expectancy at birth is estimated at 54.8 years, which is a reflection of persistently high rates of poverty and the severe effects of the HIV/AIDS crisis and other health issues. Additional problems include over-dependence on subsistence production and rain-fed maize production and consumption, which contributes to diets that lack diversity and are poor in micronutrient-rich foods. In recent years, Malawi has been experiencing the effects of climate change, which has led to food insecurity and contributes to widespread poverty among the population and persistently high rates of undernutrition.

Nutritional situation

Child undernutrition is one of the major problems in Malawi, with a national stunting prevalence of 47%. The double burden of malnutrition is on the increase, with an estimated 5.1% of children under five years old overweight (NSO, 2014), while according to the Global Nutrition Report, 22% of adults are overweight and 5% are obese (IFPRI, 2015). Despite the many challenges, Malawi has made some progress in combating undernutrition and in improving food security for its population. Key considerations regarding undernutrition include:

Stunting

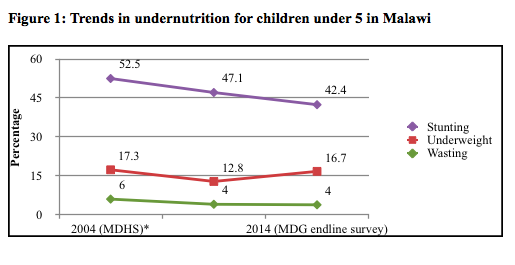

Stunting remains the major nutritional problem in Malawi, although there are reasons to be optimistic. The Demographic Health Survey (DHS) survey of 2010 showed that stunting had reduced by 1% per year since 2004.The Millennium Development Goals (MDG) end line survey conducted in 2014 (using the UNICEF Multiple Cluster Indicator Survey 1, showed a decrease of stunting at national level from 47% in 2010 to 42% in 2014 (see Table 1 and Figure 1). This survey did, however, highlight regional differences where some districts registered an increase while others registered a decrease; for example, stunting in Chiradzulu District decreased by 15.3%, while rates in Salima District increased by 7.5% (DHS 2010; MICS 2014). At present, there is only some understanding of why stunting is reducing in some areas and increasing in others; urban areas tend to have higher stunting rates (particularly severe in Lilongwe (52.4%) and Blantyre (47.8%)), likely due to limited interventions, poor water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) and other infrastructure, and high rates of migration from rural areas.

A worrying aspect of the high stunting prevalence in Malawi is the rate of severe stunting at 16.3% (MICS 2014). This is of concern because of the increased mortality risk associated with severe stunting (x 5.5), which is even higher than that for moderate acute malnutrition (x 3.4 times more likely to die than a healthy child) (Olofin, Macdonald, Ezzati et al, 2013).

Wasting

The MICS survey of 2014 found a national wasting prevalence for children under 5 years old of 3.8% global acute malnutrition (GAM) and 1.1% severe acute malnutrition (SAM). This means that Malawi has reached the World Health Assembly target “to reduce and maintain wasting of less than 5%”; a major achievement. This will, in part, likely be due to the extended efforts over the last 12 years to scale up Community Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM) programming across the country. Malawi has made great strides in integrating CMAM programmes into routine health services (something that many countries have struggled with). CMAM interventions continue to be relevant due to the high levels of mortality associated with acute malnutrition, although with GAM rates remaining at low levels, it will be important to ensure that maximum value is extracted from these interventions, considering the high cost of CMAM programming (ENN, 2012).

Table 1: Trends in nutrition status for children under 5 in Malawi, 2004-14

| Indicator | 2004 (DHS) | 2010 (DHS) | 2014 (MICS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stunting (%) | 53 | 47.1 | 42.4 |

| Wasting (%) | 6 | 4 | 3.4 |

| Underweight (%) | 17 | 13 | 16.7 |

Micronutrient deficiencies

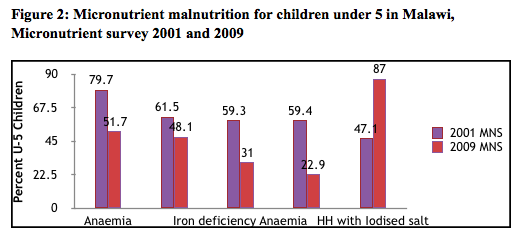

Micronutrient deficiencies have also been steadily reducing. According to the National Micronutrient Survey conducted in 2009, vitamin A deficiency declined from 59% to 23% and iron deficiency anaemia from 59% to 34% in 2001 and 2009 respectively (among children aged six to 36 months old) (see Figure 2). It is important to note that most of the gains in reducing micronutrient deficiency have been made through the provision of supplements (using a ‘medical model’), rather than from increasing the quality and diversity of diets. Currently there is a global push for agriculture to invest in developing more micronutrient-dense crops, while continuing research on the production of livestock and small animals, fish, vegetables, legumes and pulses. Bio-fortification of food offers great potential, given the largely agro-based economy in Malawi, although key to achieving maximum gains from bio-fortification will be to ensure a focus on awareness-creation of the benefits amongst the general public.

The response to undernutrition

The Government of Malawi (GoM) placed nutrition high on the government agenda by ensuring nutrition was one of the key priority areas in the Malawi Growth and Development Strategy (MGDS 2011-16). The GoM also formulated the Multi-sector National Nutrition Policy and Strategic Plan (2007-2012), which was guided by the ‘three ones principle’, i.e. one coordinating office, one strategic plan and one monitoring and evaluation plan. The policy guides the multi-sector platform in the implementation of the national nutrition response. The policy is currently being reviewed to align with global and national emerging issues. The Department of Nutrition and HIV&AIDS (DNHA) is the coordinating office for nutrition, placed under the Ministry of Health with autonomous responsibility for multi-sector coordination (the DNHA was located in the Office of the President and Cabinet until early 2015). The DNHA is mandated to provide strategic policy direction, guidance, oversight, coordination, technical support, highest-level policy advocacy, resource mobilisation and capacity-building for nutrition, to ensure increased involvement in multi-sector efforts to reduce malnutrition.

There is strong political commitment to addressing hunger and undernutrition, as evidenced by Malawi being ranked third in the 2015 Hunger and Nutrition Commitment Index (HANCI) out of 45 developing countries (www.hancindex.org). Nutrition is a priority area in the MGDS and a range of nutrition-focused policies have been put in place over the past eight years. Furthermore, Malawi has instituted a separate budget line for nutrition, improving public oversight and accountability for spending. Commitment to budget allocations for nutrition by government, through the Nutrition for Growth and the G8 New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition, has increased from 0.1 to 0.3% by 2020. While this represents more than doubling the allocation, the very low starting point means that more earmarked funding will be required to address undernutrition in Malawi effectively.

Prior to the National Nutrition Education and Communication Strategy (NECS) programme development, (see below), the GoM (with support from key partners) had been implementing a number of nutrition interventions. Nutrition-specific programmes included the CMAM programme, micronutrient supplementation through routine and health campaigns, zinc supplementation for management of diarrhoea, food fortification (sugar and salt) and biofortification (sweet potatoes and beans). Nutrition education and nutrition-sensitive programming began to be emphasised when Malawi joined the SUN Movement (see below).

Scaling Up Nutrition

Malawi was one of the first countries to join the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) movement in 2011 as an ‘early riser’. At the same time, partners in Malawi realised that while nutrition programming had been focused on very successful treatment models (e.g. CMAM), energy was required to devise and implement behaviour change programming to address prevention issues, with a particular focus on the ‘how’ of preventative programming. A gap analysis was conducted to identify key focus areas to be scaled up to reduce stunting, with nutrition education identified as a key gap. To operationalise SUN aims and principles, the NECS was developed in 2012 with funding from the main nutrition donors (Irish Aid, World Bank, USAID, DFID, EU and DFATD (formerly CIDA)). UN agencies such as UNICEF, WFP and FAO and civil society partners were also actively involved in the development of NECS. The NECS manual was developed in consultation with partners; care was taken to ensure that all messages and materials developed were harmonised and standardised.

The NECS embraced multi-sector coordination, which resulted in creation of coordination platforms at national, district and sub-district, levels. The operationalisation of NECS used the multi-sector approach, which involved key sectors including the ministries of agriculture, health, education, gender/community development, local government, finance, information, trade and industry. The media was also seen as an important ally in the dissemination of information for the NECS.

The SUN/NECS is designed to foster a multi-sector approach to addressing malnutrition at community level. It aims to bring together key stakeholders implementing both nutrition specific (direct) and sensitive (indirect) interventions. The NECS programme was developed primarily to standardise and harmonise nutrition education messages for promotion of effective behaviour change for the prevention of malnutrition. District rollout plans for NEC, have been developed and adopted by all districts in Malawi, with support from various partners including Irish Aid, USAID, DFATD, World Bank, UNICEF and WFP.

The multi-sector platform put in place to support operationalisation of the NECS included establishment of the National Nutrition Coordination Committee and the SUN learning forum at national level and the District Nutrition Coordination Committees (DNCC) at district level. The DNCC is chaired by the District Commissioner and has representatives from various sectors including health, agriculture, education and the civil society organisations working in the district. The DNCC therefore provides the technical support for the operationalisation of the NECS, with the various sectors supplying the technical support for implementation and rollout. At sub-district level, the Area Nutrition Coordinating Committee (ANCC) is chaired by the Traditional Authority. At village level, the Village Nutrition Coordinating Committee is chaired by the group village headman. This committee has membership of front-line workers from the ministries of agriculture, health, gender, education and other civil society organisations. At village level, there is also the Area Community Leaders Action for Nutrition (ACLAN) structure, responsible for community sensitisation and mobilisation.

Successes/strengths of the SUN/NECS initiative

Leadership for the programme was strong from the start, using energetic, persistent and continued advocacy to ensure that nutrition was placed centre stage (even before the NECS programme began) and that it stayed there. Partners understood that patience and resolve were required to maintain the belief that working together would be worth the effort, and that everyone’s combined efforts would be more than the sum of the parts.

The NECS manual is comprehensive and well developed, based on the suggested actions of the internationally agreed Essential Nutrition Actions (ENA) approach. Using the data and evidence for ‘what works’, the manual is clear and comprehensive regarding breastfeeding and complementary feeding, and has key education messages on hygiene and improved sanitation. Many stakeholders reported that the major success of NECS is the harmonisation of education and behaviour change messages; all partners use the same messaging and materials across the country. It was described by one interviewee as “like a Bible for Malawi – the go-to reference document for how to implement preventative nutrition programmes.”

Establishment of the DNCCs has raised the profile of nutrition issues and empowered the districts to address them. While some districts are more successful than others (depending on the length of time the DNCC has been established, how much capacity there is in each district and district commitment towards nutrition), for the most part nutrition has been successfully ‘mainstreamed’ across the various sectors.

Establishment of structures, such as community care groups at district level, have been very successful. One of the strengths of NECS is that all government staff at district level are involved at one stage or another in the multi-sector planning, with nutrition becoming central at district level. The use of institutionalised structures for SUN in Malawi has greatly benefited the delivery of the nutrition programme at community level, including Village, Area and District Nutrition Coordination Committees. These structures have helped to create demand-driven ownership of nutrition services across and amongst communities.

Through the National Multi Sector Platform, support was provided to align funding for nutrition activities from development partners, which has helped to prevent duplication of efforts (although this still proved challenging – see below).

In terms of monitoring and evaluation, Malawi developed a Multi Sector Monitoring plan and web-based reporting system, which has been rolled out in almost 50% of the districts. A web-based resource tracking system was also developed to help track nutrition financing in Malawi.

A good understanding prevails that it is important to be flexible for adapting, monitoring and learning. Efforts were made to extract learning from the start (with a gap analysis) and as the programme has matured. A bottleneck analysis was conducted early on, and regular (annual or biannual) learning forums have been organised to share experiences and capture learning. In this way, SUN/NECS programming in Malawi has attempted to be iterative.

The civil society network (CSONA) has been well organised and provided excellent support for the NECS rollout. There is a good understanding in Malawi of the importance of civil society for its crucial role in improving nutritional status of the population.

Challenges

The SUN/NECS initiative has not been without its challenges, which include:

- Fragmentation of funding of NECS rollout

As the NECS programme has no direct funding (it comes from the various partners to the various districts), funding can be variable, inconsistent and fragmented. Activities in particular districts can be dependent on which partner has funding available, what aspects they focus on and at what scale.

- Monitoring and accountability challenges

For some years, coordination and monitoring of NECS has been a challenge, particularly in the collection and transfer of data from community up to national level. A new integrated reporting system has been established with support from the World Bank; this is expected to improve monitoring and evaluation of all nutrition activities, including for NECS.

- Delays in translation of the Social Behaviour Communication Change (SBCC) material

Some delays in translation of the materials needed to implement the programme were experienced, which meant there were delays in many districts between the training and commencing activities. This was resolved after a few months, since when supplies and logistics have been mostly constant.

- Competing/contradictory roles for civil society actors

At district level, the dual roles of civil society actors to support the DNCC with coordination, while at the same time ensuring that the main protagonists for the programme are held to account, can sometimes be sensitive to navigate.

- Insufficient attention to the period of pregnancy and pre-conception

While the NECS manual is well developed in terms of the infant/child, the period of pregnancy – or the first 280 days of the critical 1,000 days – is not well addressed in the manual. It is well understood that approximately 20% of stunting is pre-determined at birth (Black, Victora, Walker et al, 2013), so it is imperative to ensure that maternal nutritional needs are addressed, both for the sake of the mother in her own right, as well as for optimising the health and nutritional status of the newborn. Considering that Malawi has a low birth weight (LBW) rate of 12.9% (LBW is an indication that things have not gone to plan during the pregnancy), the issue of supporting maternal nutrition is vitally important.

- Limited engagement with the private sector

While attempts have been made to establish the business network in Malawi, as yet there has been limited engagement with and uptake from the private sector. The National Fortification Alliance meets quarterly, which provides a platform for public-private-partnerships. There is, however, much scope to develop linkages with the private sector further to promote a healthier food environment. Malawi is beginning to struggle with the double burden of malnutrition; it is therefore vital to engage the private sector in efforts to reduce food insecurity and undernutrition, as well as to halt the rising tide of overweight and obesity amongst the population.

Conclusions

The stakeholders interviewed for this article report that the NECS programme has been very successful to date. It has benefited from strong political commitment and support; well coordinated structures through the various networks (particularly the civil society and donor networks); efforts to coordinate funding; development of a well thought-through strategy; and extensive efforts to learn lessons as the programme matures. Actors in Malawi must be commended for developing and implementing this important programme. While there have been a number of challenges with rolling out a large national programme, suggestions from key stakeholders for future actions to improve the programme further are as follows:

- Many stakeholders reported that key to the success of the NECS rollout is continued and extended support for the DNCC. Most felt that this structure offered the best hope for well-coordinated, multi-sector work at district level, although there is concern that some of the districts lack sufficient nutrition capacity.

- A comprehensive review/evaluation of the NECS programme to date is considered an important next step. This would clearly articulate the successes, challenges and main learning points from the rollout so far. At this stage, more inclusion/emphasis on maternal nutrition and the importance of healthy families were suggested by most stakeholders.

- Further coordination and standardisation of funding modalities and areas is needed.

- Additional effort is required to engage with and include the private sector in SUN efforts.

For more information, contact: Felix Pensuo Phiri

References

1;Although MICS surveys use different sampling and methodology to DHS, many stakeholders in Malawi consider the results to be comparable.

Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, Bhutta ZA, Christian P, de Onis M, Ezzati M, Grantham-McGregor S, Katz J, Martorell R, Uauy R; Maternal and Child Nutrition Study Group. (2013). Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 382(9890): 427-451.

DHS 2010. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2010 National Statistical Office Zomba, Malawi. dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR247/FR247.pdf

ENN 2012. Government experiences of scale-up of Community-based Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM): A synthesis of lessons, Emergency Nutrition Network. www.ennonline.net/cmamgovernmentlessons.

IFPRI 2015. Global Nutrition Report 2015: Actions and Accountability to Advance Nutrition and Sustainable Development. International Food Policy Research Institute. 2015. Washington, DC.

NSO 2014. National Statistical Office. Malawi MDG Endline Survey 2014, Key Findings. Zomba, Malawi: National Statistical Office.

Olofin I, McDonald CM, Ezzati M, Flaxman S, Black RE, Fawzi WW, Caulfield LE, Danaei G; Nutrition Impact Model Study (2013). Associations of suboptimal growth with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in children under five years: a pooled analysis of ten prospective studies. PLoS One 8(5): e64636.