Changes to Nutrition Cluster governance and partnership to reflect learning and operational realities in Somalia

By Samson Desie

By Samson Desie

Samson Desie is Nutrition Specialist working in the sector for more than a decade and currently working as Nutrition Cluster Coordinator, with UNICEF Somalia.

The ENN team supporting the development of this case study comprised Valerie Gatchell (ENN consultant and project lead), with support from Carmel Dolan and Jeremy Shoham (ENN Technical Directors). Josephine Ippe, Global Nutrition Cluster Coordinator, also provided support.

The author would like to acknowledge all the members of the Somalia Nutrition Cluster Strategic Advisory Group for their review and input into this document and their support in the process.

This article is a summary of a case study produced through a year-long collaboration in 2015 between ENN and the Global Nutrition Cluster (GNC) to capture and disseminate knowledge about the Nutrition Cluster experiences of responding to Level 2 and Level 3 emergencies (available at www.ennonline.net/ourwork/networks/gnckm). The documented findings and recommendations are those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of UNICEF, its Executive Directors or the countries that they represent and should not be attributed to them.

Location: Somalia

What we know: Somalia has a long history of conflict and insecurity and is a particularly challenging operational enviornment to coordinate nutrition programming. The nutrition situation is chronically poor, characterised by prevalent acute malnutrition.

What this article adds: This case study details the limitations around the rapid expansion of nutrition services in Somalia in response to the 2011-2012 famine and subsequent rationalisation of the Nutrition Cluster to improve nutrition coordination, governance and service delivery. Key learning from this process is identified. The new way of working is centred on accountability to affected populations, greater partner inclusivity, a more representative steering advisory group, focused working groups, two dedicated in-country coordination positions, and attention to sub-national coordination. The Nutrition Cluster is engaged in a nascent SUN movement in Somalia. Outstanding challenges include lack of funding, insecurity and difficult monitoring.

Country overview

Since the early 1990s, Somalia has been plagued by violence and insecurity, resulting in large population movements and several internally displaced people’s (IDP) camps in the south. Insecurity remains a large threat due to clan fighting and Al-Shabaab activity. Since September 2012, Somalia has been guided by an internationally supported plan (Vision 2016) with the aim of federalising by the end of 2016.

Somalia suffers from a chronically poor health and nutrition situation, characteristed by prevalent acute malnutrition (national prevalence of GAM>15%, higher amongst the displaced); micronutrient deficiencies (iron deficiency anaemia, vitamin A) at WHO emergency levels, and poor feeding practices (5.3% exclusive breastfeeding rate, 17.1% timely introduction of complementary foods1

Nutrition service delivery

Nutrition service delivery is guided by the Somalia Nutrition Strategy (SNS). The Joint Health and Nutrition Programme (JHNP) implements a Basic Nutrition Services Package (BNSP) that includes Maternal and Child Health, Expanded Programme on Immunisation, Nutrition, and Hygiene Sanitation promotion, and that encompaasses management of acute malnutrition. However, nutrition service delivery is fragmented and there is duplicative humanitarian/development programming.

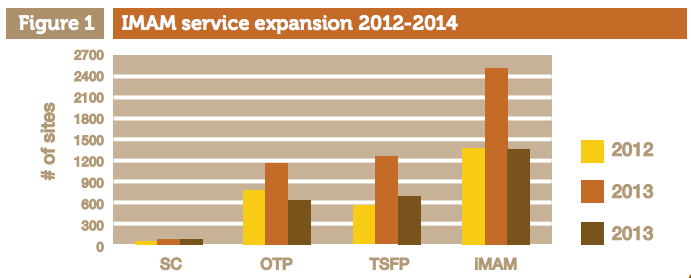

Nutrition Cluster (NC) partners largely work under these policies and services to address acute malnutrition through an Integrated Management of Acute Malnutrition (IMAM) approach. In 2011, in response to the 2011-12 famine, the NC launched a rapid scale up of IMAM services including inpatient therapeutic care via Stabilisation Centres (SC), outpatient therapeutic care programmes (OTP), and supplementary feeding programmes (SFP). IMAM service plans outlining services to be delivered and identifying partners were developed for each district with partners, UNICEF and local authorities.

Limitations and challenges as a result of scale-up

Because of the urgency of the famine response, expansion and opening of new service delivery points was driven largely by need and access rather than as part of a strategic process. While integration of the delivery of health and nutrition services was promoted at the strategic level (e.g. Strategic Response Plan (SRP)), at an operational level, health and nutrition service delivery remained largely fragmented due to institutional segmentation and parallel health systems and structures, with different modalities for financing1 in the South Central Zone (SCZ). Some areas were “over-served” while others had limited service, with multiple and mixed layers of agency partnership and conequent duplicative funding and administrative mechanisms.

Rationalisation 1.0

Towards the end of 2012, there were noticeable improvements in the nutrition situation and a decline in humanitarian funding. In response, in 2013, the NC embarked on a consultative programme rationalisation process (Rationalisation 1.0) to develop district service plans for nutrition in SCZ. (Rationalisation refers to the process of reviewing nutrition needs geographically and redistributing partners to cover gap areas.) The process considered capacity, access, expected caseload and clan affiliation among other issues. Through this process, one partner was selected based on its comparative advantage over others to deliver services in a given district.

While Rationalisation 1.0 was conducted collaboratively and partners were identified to provide nutrition services across SCZ, major challenges remained around service delivery, selection of partners and monitoring. These are detailed below.

Nutrition programme service delivery challenges

- There was no clear strategy for integrating nutrition into primary health care services.

- The rollout of JHNP/BNSP (which aimed to shift from vertical to horizontal programming and integrate health and nutrition services) began towards the end of 2013, in the middle of Rationalisation 1.0. No guidance was provided on how to account for other programmes and funding streams in the district planning process.

- Post-emergency integration of IMAM into state services was not feasible due to absence of a long-term nutrition plan. Additionally, there was no guidance on what should constitute a long-term IMAM service plan and what should be considered a short-term emergency/surge (preparedness) programme.

- Lack of flexibility from a few partners in readjusting their programme plans to conform to the rationalised service plans resulted in overlap of programmes in some areas and gaps in services in other areas.

- Lack of standardisation of admissions criteria for OTPs and SFPs led to lack of operational alignment in some districts.

- Partners largely had funding for one nutrition service (for example, inpatient treatment of acute malnutrition) with no capacity for other related nutrition services (minimum nutrition services were only agreed in November 2015). Children in OTPs were therefore not discharged to SFPs or admitted to the inpatient care facility as needed.

- Lack of clear criteria for defining mobile OTP and TSFP sites sometimes led to arbitrary and unverifiable sites ( that were not located in Somalia.

Selection of partners

- In some regions (e.g. Bakool, Bay, Galgaduud, Benadir), consensus amongst implementing partners on geographic areas of programme coverage was not possible due to some partners’ inability to shift due to access and funding issues. In such cases, the NC, in collaboration with UNICEF and WFP, chose the implementing partners they would support.

- Clan and access considerations made it difficult to settle on one or two partners per district and in some cases, clan authorities recommended multiple partners.

- The absence of harmonised risk management criteria and transparency across agencies resulted in different levels of risk assessment for partners and inconsistent approaches to securing partners as a result.

- A parallel planning and selection process for BPHS was being undertaken with differing criteria and timeframes, which created challenges for partnership selection.

- Some partners did not share details about their longer-term funding and therefore plans of some long-term partners could not be factored into the rationalisation process.

Monitoring

While the Food Security and Nutrition Unit (FSNU) surveys are conducted twice a year, there is no routine nutrition surveillance mechanism in Somalia (i.e. there is no routine growth monitoring at health centres or OTP/SFP sites). Partners had limited capacity to produce quality reports (reports produced were often incomplete and delayed) and conduct informative, rapid assessments. This has led to a slow response to emerging hotspots. Additionally, verification of a partner’s capacity and operations was limited due to insecurity and access. While third-party monitoring was thought to address this, conflict of interest and collusion have caused this to be largely ineffective.

Rationalisaiton 2.0

As a result of the challenges to service delivery identified above in early 2015, the NC embarked on a second rationalisation process, Rationalisation 2.0. This aimed to revise service delivery collaboratively with a focus on ensuring services to the most vulnerable. It also aimed to decrease the overall number of partners implementing nutrition services without compromising service delivery. The concept of primary, secondary and tertiary partners was introduced whereby the primary partner is accountable for ensuring nutrition services for the entire district whenever and wherever possible. Primary partners would be able to work in partnership with either the secondary or tertiary partner to ensure complete geographic coverage of all services throughout the district. Secondary and tertiary partners were identified in case a primary partner failed to secure resources, could not cover the entire district, and/or failed to provide services on time.

While there is no systematic linkage to the cluster, in consultation with partners and the JHNP team, the NC gave priority to JHNP partners in districts where JHNP exists. As primary partners, it is assumed that they can absorb the nutrition caseload. However, if acute malnutrition increases and surge capacity is needed to support a greater number of cases, the NC has a secondary and tertiary partner in place to support the additional need.

The process for Rationalisation 2.0 has consisted of:

I. Mapping current service delivery, verified by the Strategic Advisory Group (SAG) (independent geotagging of sites to be conducted).

II. Review and/or development of IMAM service plans (including therapeutic feeding and supplementary feeding) with defined criteria for static, outreach/mobile services.

III. Selection of organisations to implement the IMAM service plan using defined eligibility criteria and taking into account potential caseloads and partner capacity.

The NC coordinated a network of 141 active partners (pre Rationalisation 2.0), of which almost 80% (111) are national NGOs, mostly based in SCZ. Almost all national NGOs worked in partnership with INGOs and UN agencies, often with an overlap of contracts and/or a chain of sub-contracts. After Rationalisation 2.0, there were 99 partners, of which 71% (70) are national NGOs.

Mutual respect and accountability have guided the process, upheld through the partners’ common commitment to the principles of partnership. Value for money and ensuring economies of scale were also considered in partner selection.

While the process is ongoing, experience to date highlights the need to delicately manage conflict of interest (arising from partners influencing government officials and local authorities) and partner/government expectations, given the reduction in number of partners resulting from the process. Allowing time for these issues to be addressed has extended the process but has enabled wider discussion on accountability to affected populations, which has dispelled some of the competition among partners. A concurrent shift in NC governance has supported this new approach to service delivery.

Nutrition Cluster governance 2011-2013

The NC was fully functioning and led by a Nutrition Cluster Coordinator (NCC) and Information Management Officer (IMO) during the rapid scale-up and Rationalisation 1.0. However since late 2013, nutrition coordination has been significantly weakened, in large part due to a 10-month absence of an NCC, weak government engagement in the NC (due to lack of technical capacity and political instability) and a policy shift in the coordination forum (moving coordination from Nairobi to Mogadishu). Regular coordination functions essentially collapsed.

National NC coordination meetings were being held on a monthly basis in Nairobi, Kenya until 2013, but due to international pressure to support the Transitional Government of Somalia (TGS), nutrition coordination was officially relocated to Mogadishu in November 2013. Mogadishu meetings are chaired by a national Cluster Support Assistant and co-chaired by the MoH representative from the Federal Government of Somalia. These meetings have been largely ineffective, due mainly to the limited number of partners regularly operating in and around Mogadishu and the absence of decision- makers at meetings. Due to insecurity, international staff, including the Nairobi-based coordination team, are unable to travel to Mogadishu to participate in the meetings. Additionally, NC partners from different parts of Somalia faced security challenges in travelling to Mogadishu.

During this time, Somali sub-national nutrition coordination mechanisms also came to a standstill. UNICEF programme staff supported coordination efforts in terms of collecting reports at sub-national level in some areas. Additionally, UNICEF programme staff represented the cluster in the Inter-cluster Coordination Group (ICCG) and Humanitarian Country Team. This shift of representation from dedicated cluster staff to UNICEF programme staff (“double-hatting” to cover cluster coordination functions) created confusion among partners regarding the responsibilities of UNICEF as a partner and as the Cluster Lead Agency (CLA) for Nutrition.

Cluster functions in Somalia were poor and limited to a few operational tasks during this period. The 2014 Somalia Nutrition Cluster Performance Evaluation also indicates that five out of seven key cluster functions were “weak”. These were: informing strategic decision-making of the Humanitarian Coordinator/Humanitarian County Team (HC/HCT) for the humanitarian response, planning and strategy development, advocacy, contingency planning/preparedness, and accountability to affected population.

The NCC post was eventually filled in December 2014 and a review of the cluster and coordination mechanisms was conducted. A two-day (12-13 January 2015) consultative workshop was organised to revitalise the coordination mechanism and identify a more systematic and integrated approach. This involved 66 participants representing the management and technical team of all partners and stakeholders, high-level MoH officials (Director Generals) and the UNICEF Representative for Somalia. Plans for maintaining coordination in Nairobi, restructuring zonal nutrition cluster sub-coordination mechanisms, activation/ re-establishing of key working groups and rationalisation of partners were reviewed and agreed.

The workshop also endorsed the strategic documents developed by the NCC, including a roadmap for the NC, the Somalia NC strategic operating framework and annual work plan (2015), Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for nutrition surveys and assessments, an annual calendar for zonal nutrition cluster sub-coordination and draft simplified guidance for estimating severe acute malnutrition burden and target caseload. Following the workshop, relevant guidance notes, NC SOPs and terms of reference for Working Groups were developed and endorsed.

Shifting to this new structure and way of working has been a gradual process. Each structure was reviewed and agreed upon through a series of consultations at Nairobi and field level.

New governance structure and way of working (2015)

Accountability to affected populations (AAP). The new way of working is centered around ensuring AAP through coordinated and inclusive systems. Partners are required to sign a Memorandum of Understanding articulating their accountability to the population and committing to uphold AAP principles.

Inclusivity. As a result of the workshop, cluster partners agreed to function in a more inclusive and integrated manner. To this end, key cluster functions will be shared with specific partners and working groups for collective accountability, responsibility and shared vision and/or ownership with full oversight of the cluster coordination.

SAG. The SAG was re-established as the highest decision-making body for the cluster and it was collectively agreed that the SAG would maintain neutrality, independence and representation of the cluster partners. The SAG is composed of nine members; three local NGO representatives (increased from one previously), two international NGO representatives, two UN (UNICEF & WFP), one government official (Director General) and a representative of the Somalia Nutrition Consortium (which is made up of four INGOs). While UNICEF and government hold permanent seats, others rotate annually for membership and biannually for chairmanship among the members. The government will continue to co-chair the various meetings wherever and whenever possible.

Working groups. Working groups are to be specific and partner-led with oversight from the SAG. A working group on Assessment and Information management (AIMWG) has been established and is chaired by the Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit (FSNAU).

Human resources. Through strong backing and support of UNICEF as the CLA, two new posts for in-country coordination have been agreed upon. Hiring of these staff was ongoing as of October 2015. Additionally a capacity development plan is being developed by the CLA and strong technical partners to strengthen technical capacity of all partners and improve service delivery and AAP.

Sub-national coordination. Chairs and co-chairs for 11 sub-national coordination mechanisms have been elected.

Coordination meetings. Sub-national coordination and working group meetings have been streamlined so that discussions and outputs of one meeting feed into the next. Sub-national and Mogadishu-based meetings will be held on a monthly basis with available partners. These feed into quarterly sector coordination meetings chaired by government (with NC coordination representation and support) in Mogadishu. Outcomes and follow-up actions of the monthly cluster and quarterly sector coordination meetings will inform the agenda of the Nairobi level cluster coordination meeting, which will be held on a quarterly basis. Finally, the SAG and AIMWG will convene monthly and on an ad-hoc basis as necessary.

The NC and Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN)

Somalia joined the SUN movement in March 2014, although there was limited traction until a new Prime Minister was appointed in September 2015. Somaliland and Puntland have also joined the SUN movement and have already developed multi-stakeholder platforms. Currently a committee is working to establish the multi-stakeholder platform for Somalia-Mogadishu. The NC is fully engaged in supporting the SUN movement as documented in the Strategic Response Plan (2016) and it is actively linking its network of partners on the ground. The NCC or NGO co-chair engages in the SUN platform meetings.

Lessons learned

Reflection on the process of rationalisation and restructuring the governance and way of working highlights the following points of learning:

- An extended gap in presence of an NCC and lack of NC architecture led to absent NC coordination. Shifting coordination responsibilities to UNICEF programme staff (double-hatting) created confusion amongst partners on the role of the NC and the CLA.

- While politically appropriate, moving coordination activities to Mogadishu has necessitated the continuation of Nairobi-based coordination activities, thus adding an additional layer of coordination.

- The new way of working, grounded in strong leadership by the NCC, has fostered increased trust, transparency, openness and working relationships among partners and strengthened credibility of the NC. It has resulted in increased support and buy-in around cluster activities (eg leading working groups, SAG membership) and honest discussion around issues leading to effective solutions.

- Expansion of SAG membership to include three local NGOs (instead of just one), together with clarity of SAG role, has increased NC credibility, partner engagement and the feeling of inclusiveness.

- Incorporating AAP at the highest level in the NC to focus on the affected population has resulted in greater sharing of resources to cover a vulnerable area and recognition of partners’ comparative advantages and capacity when selecting primary, secondary and tertiary partners in the Rationalisation 2.0 process.

- Expansion of the SAG’s role in coordination, increasing partners’ role in working groups and securing additional staff to support cluster functions distributes the NC workload and allows for wider participation of partners. In the absence of an NCC, working group activities can still move forward with leadership and direction of the lead agency and the SAG.

- There is need for a political analysis when programming through local partners within a clan-based governance system. Including Director Generals of Health from Somaliland and Puntland in NC meetings and dialogue has fostered a wider understanding of nutrition coordination issues faced in these other regions and has improved Director Generals’ support for nutrition coordination initiatives launched by the NC.

- Strong leadership from the NCC combined with robust technical capacity of the NC team members and partners has allowed the NCC/NC staff to focus on coordination issues.

Conclusion

While there have been significant advances in nutrition coordination through 2015, the rationalisation process and governance restructuring still face challenges including lack of funding, insecurity and weak monitoring. Yet, due to the strength of the collective and strong leadership, nutrition coordination in Somalia is now in a very strong position to advocate for and implement nutrition priorities. Additionally, there is potential for the NC to guide and support the SUN movement, particularly with regard to integrating preparedness planning and emergency response planning in multi-sector plans. This would strengthen nutrition capacity in Somalia significantly.

For more information, contact: Samson Desie; or UNICEF

References

1 FSNAU National Micronutrient and Anthropometric Survey, 2009

2 These include: public sector funding (2-4% of the total budget is ear-marked for health); United Nations Development Assistance Framework (UNDAF) humanitarian funding; the SRP (CHF, CERF); JHNP (funding mainly from DFID, AusAID, Sweden, USAID, Finland and Swiss); and Islamic Organizations Cooperation (IOC) funding (UAE, Turkey, Qatar, etc.).

Also see: Global Nutrition Cluster knowledge management: process, learning