Scaling up nutrition services and maintaining service during conflict in Yemen: Lessons from the Hodeidah sub-national Nutrition Cluster

By Dr. Saja Abdullah, Dr. Rasha Al Ardi, and Dr. Rajia Sharhan

Dr. Saja Abdullah is Chief of Nutrition with UNICEF Yemen

Dr. Rasha Al Ardi is Health and Nutrition Office and Sub-cluster Coordinator for Hodaida zonal office, Yemen.

Dr. Rajia Sharhan is a Nutrition Specialist with UNICEF (formerly based in Yemen).She has worked in the CMAM programme in Yemen for 10 years, working to scale up nationwide from 2006 up to 2015.

The ENN team supporting this work comprised Valerie Gatchell (ENN consultant and project lead), with support from Carmel Dolan and Jeremy Shoham (ENN Technical Directors). Josephine Ippe, Global Nutrition Cluster Coordinator, also provided support.

The findings and recommendations documented in this case study are those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of UNICEF, its Executive Directors or the countries that they represent and should not be attributed to them.

Location: Yemen

What we know: Yemen is the poorest Arab nation, embroiled in lengthy political crisis and ongoing conflict. Malnutrition is a major and chronic problem; international humanitarian access is compromised.

What this article adds: The Nutrition Cluster was established in the Yemen in 2009, co-led by the Ministry of Public Health and Population and UNICEF. There are five sub-national clusters. Through 2012-14, scale up of nutrition services (SAM and MAM treatment, IYCF, micronutrient supplementation, strengthened reporting), combined with multi-sectoral interventions led to an improved nutrition situation in Hodeidah governate. The majority of programming has been government led; local NGOs have been an integral part of the provision of health and nutrition service delivery. Ongoing challenges include poor integration of SAM/MAM services, failure to address prevalent stunting, funding gaps and escalating conflict compromising service delivery and access further. The SUN Movement multi-sector plan, finalised and pending implementation, offers an opportunity to connect emergency and development programming.

Country overview

Yemen is the poorest Arab nation, characterised by high unemployment (40%, geopoliticalmonitor.com), rapid population growth (45% of the population are below the age of 15) and diminishing water resources. The economy, heavily dependent on dwindling oil supplies (expected to end by 2017), has been severely disrupted by a lengthy political crisis and conflicts on several fronts spanning a number of years. Fighting escalated in March 2015, exacerbating an already severe humanitarian crisis with large scale population displacement, destroyed civilan structures, including hospitals and schools, and near collapse of basic services. There are widespread fuel shortages (reduing export earnings) and extremely limited access to water in many areas.

Yemen is the poorest Arab nation, characterised by high unemployment (40%, geopoliticalmonitor.com), rapid population growth (45% of the population are below the age of 15) and diminishing water resources. The economy, heavily dependent on dwindling oil supplies (expected to end by 2017), has been severely disrupted by a lengthy political crisis and conflicts on several fronts spanning a number of years. Fighting escalated in March 2015, exacerbating an already severe humanitarian crisis with large scale population displacement, destroyed civilan structures, including hospitals and schools, and near collapse of basic services. There are widespread fuel shortages (reduing export earnings) and extremely limited access to water in many areas.

Health, nutrition and food security

An estimated 8.4 million people lack access to basic healthcare and maternal mortality is high. An estimated 13.4 million people lack access to safe drinking water and 12 million people have no proper sanitation facilities (UN OCHA, 2015). Malnutrition is a major and chronic problem in Yemen. Stunting is prevalent (47% in 2011; IFPRI, 2014); acute malnutrition is estimated nationally at 16% (DHS 2014), although there are areas where this is significantly higher. Yemen suffers from the double burden of malnutrition; 46% of adults are overweight and 17% are obese (WHO, 2008). Anaemia affects 38% of women of reproductive age and 27% of school-aged children are vitamin A deficient (IFPRI, 2014). While breastfeeding is common in Yemen (97% of all women breastfed), infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices are characterised by low timely breastfeeding initiation rates (40%) (MICS, 2006), very low exclusive breastfeeding rates (12%) (UNICEF 2003), and a high level use of feeding bottles (42% use in 0-3 months, Yemen Family Health Survey, 2003).

Nearly half (46%) of the population (12 million people) are food insecure (WFP Sit Rep #8, 28 May 2015). Almost all food (90%) is imported and prices have increased due to disruption in food supply routes and sporadic transportation services. Meanwhile, household incomes have decreased due to the devaluation of the local currency.

The Nutrition Cluster

The Nutrition Cluster (NC) was established in August 2009 following a large-scale Yemeni military response to the Houthi rebels in Sa’ada, northern Yemen. The NC is co-led by the Ministry of Public Health and Population (MoPHP) and UNICEF at both national and sub-national levels. A steering committee comprised of both international and local NGOs1 identifies key strategic areas of focus for the work plan and reviews progress of response and emerging priorities. At national level, there are 35 active partners, approximately 25% of which are local NGOs (LNGOs). At sub-national level, local NGOs often make up a higher percentage of partners. An Information Management officer (IMO) supports both national and sub-national clusters. An Assessment Officer coordinates nutrition assessments for the cluster. There are five sub-national nutrition clusters at governorate (state) level. These are led by the UNICEF programme officer and supported by UNICEF IMOs (who support UNICEF programmes and all the UNICEF-supported clusters simultaneously). The NC is the only coordination mechanism for nutrition response in emergencies in Yemen, although under the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) movement, there is an ongoing initiative to establish a development-orientated food security and nutrition coordination platform.

Hodeidah and Hajjah Sub-Cluster Response 2012-2014

UNICEF has been involved in supporting health and nutrition activities in Hodeidah and Hajjah governorates since the 1990s, with specific support to vaccinations and Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI), community-based nutrition activities (2000) and a community-based, maternal, neonatal care programme was started in 2007. In 2008, UNICEF started community management of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) programming in Hajjah and in 2009 in Hodeidah. In 2011, the SAM caseload increased and with anecdotal evidence of deteriorating nutrition, UNICEF conducted SMART surveys in November 2011 in Hodeidah and in May 2012 in Hajjah. The surveys revealed that acute malnutrition was high in both Hodeidah (global acute malnutrition (GAM) 31.7% and SAM 9.1%) and Hajjah (GAM 19.8% and SAM 3.7%). High levels of GAM and SAM were most likely due to a long-term, gradual increase in a number of risk factors (long-term food insecurity, sporadic conflict, poor IYCF practices, and limited access to quality health care).

In response, high-priority districts, potential partners and capacity gaps for local non-governmental organisations (LNGOs) were identified collaboratively with the cluster partners and the government. Partners responded quickly to the needs in Hodeidah; however there was less partner interest in Hajjah, largely due to their limited capacity to expand operations. Sub-national clusters were established for each governorate.

Response - national level

In 2012, the National Nutrition Cluster (NNC) developed a costed, integrated, strategic response plan (SRP) for nutrition to massively scale up services to treat acute malnutrition and prevent undernutrition in Hodeidah and Hajjah and other governorates of Yemen. This plan was used at a national and international level to advocate for funding for nutrition and for a multi-sectoral response to the nutrition situation. The NNC also actively engaged in the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement (see Box 1).

Box 1: The SUN movement in Yemen and links with the Nutrition Cluster

The Government of Yemen joined the SUN movement in November 2012 and appointed the Minister of MoPIC as the SUN focal point. In April 2013, the MoPHP presented the nutrition situation of women and children in Yemen to the cabinet. Following this, the Prime Minister advised key ministries to develop an integrated, multi-sectoral response plan to address the nutrition situation and establish a technical consultation platform to support it. The MoPIC was assigned responsibility for convening and coordinating the movement and its steering committee by a government decree.

The SUN steering committee convenes a regular monthly meeting, chaired by the SUN focal point. The committee is comprised of key ministries (including MoPHP, Education, Agriculture, Fisheries, Water & Environment and Communication), UN organisations (UNICEF, WFP, WHO, UNDP and FAO), donors (UK AID, USAID, World Bank, EU), academia (University of Sana`a), the private sector (chamber of commerce representative) and civil society organisations. A SUN technical committee also meets regularly; the national-level NCC actively participates in this forum.

Under the SUN framework, finalisation and costing (US$1.2 billion) of the five-year, national, multi-sectoral nutrition plan (MSNAP) together with the Ministries of Health, Water, Agriculture, Fisheries and Education has been concluded. The NC was heavily engaged in this process and as a result, the MSNAP includes costed interventions for emergency preparedness and response in addition to longer-term, developmental nutrition actions.

The aim was to introduce the plan into the 2015 government planning and budget cycle, but due to intensified conflict and the shifting political context, it is currently ‘on hold’.

Response - Hodeidah and Hajjah governorates

The following nutrition activities were undertaken in Hodeidah and Hajjah:

- Therapeutic Feeding Centres (TFC) or Stabilisation Centres (SC) – at district level to provide inpatient care (as per WHO protocols) for severely acutely malnourished children (under five years) with complications. Training on inpatient care was provided to Health Facility (HF) staff.

- Outpatient Therapeutic Care (OTP) – at HF level (fixed and mobile teams) to treat children (under five years) with uncomplicated SAM. Children were provided with ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF), as per the Yemen National CMAM Guidelines. Training on outpatient care was provided to HF and mobile team staff.

- Treatment of Moderate Acute Malnutrition (MAM) – at HF level and within mobile teams, alongside outpatient therapeutic care. Ready-to-use Supplementary Food (RUSF) was provided to moderately acutely malnourished children (under five years).

- Integration of IYCF activities – including IYCF ‘corners’ in HF and training of community health volunteers (CHVs) on IYCF best practice. IYCF messages were also integrated into UNICEF-supported Community Development activities.

- Micronutrient supplementation – including vitamin A supplementation and de-worming (for children under five), iron/folic acid supplementation for pregnant and lactating women, and multiple micro-nutrient powders for internally displaced persons.

- Community mobilisation – activities included training community health volunteers on screening for acute malnutrition through the measurement of mid-upper-arm circumference (MUAC). Additionally CHVs were trained on communication and counselling around infant and young child feeding.

Approximately 20% of programming was taken on by NGOs and 80% by government. The Government Health Office (HO) took on the responsibility for increasing and scaling up treatment of SAM and MAM in fixed HF (with UNICEF support for supplies). Local and international NGO partners agreed to fill capacity and training gaps in temporary HFs, and establish mobile teams to access areas without services and support community mobilisation. WFP provided supplies to NGOs and the HO for treatment of MAM.

Capacity development of HF staff was required to expand CMAM activities, which included training all HW in fixed or temporary HF on CMAM protocols by the HO (with UNICEF support); technical support from international NGOs to HW working in temporary sites; and mobile teams established by international NGOs to access areas with no HF.

LNGOs have been a significant part of the provision of health and nutrition service delivery since 2011 and have been critical for the response post-2015 due to the evacuation of international NGOs. As of mid-2015, eight LNGOs were working in Hodeidah and Hajjah. The Charitable Society for Social Welfare (CSSW) and the Yemen Family Care Association (YFCA) are national and sub-national Nutrition Cluster partners; others are partners only at the sub-cluster level.

Given its extreme levels of SAM, treatment was prioritised in Hodeidah, while there was a stronger push for prevention activities in Hajjah.

Box 2: Experience with mobile teams (MTs)

In 2012, the HO alongside the nutrition sub-cluster identified several areas of Hodeida and Hajjah with no health and nutrition services. Partners agreed with MTs to provide outpatient treatment for SAM and MAM (where possible with WFP supplies/support), Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) services, vaccinations, reproductive health services, vitamin A supplementation and IYCF counselling. Once no new cases of SAM are identified, all current cases are referred to the nearest HF to complete treatment.

NGOs supported the development of 23 mobile teams (from 2012 to end 2014) to cover vulnerable districts of Hodeidah. In Hajjah, six local and international NGOs implemented mobile teams, but gaps in coverage remained. In response, the Hajjah HO developed mobile teams, building capacity of district-level health workers on mobile and key health services, and renting vehicles.

As a result, coverage of health services dramatically increased. In 2011, 1,345 children under five with SAM were enrolled from 32 districts (all of Hajjah) with a 12% cure rate. Hajjah HO MTs were launched in 2012 in three districts. By the end of the year, 1,690 SAM children under five years were enrolled (67% cure rate, 28.7% default rate). In 2013, 1,925 SAM children under five years with SAM (92% cure rate, 7% default rate). The HO mobile team had the highest performance indicators of all implementing partners. Vaccination coverage of children under one year of age dramatically increased, from 13% (2014) to 100% in six targeted districts.

The cost for an HO-implemented mobile team (US$3,000) proved much less than that of an NGO team (US$5,000-7000) with added value in building capacity of government health services.

Advocacy efforts by the HO and nutrition sub-cluster has meant WFP will provide MAM treatement supplies for all MTs from 2015. By the end of 2014, the HO (with UNICEF support including vehicle rental and health worker daily fees) was supporting nine mobile teams. Plans for expansion are on hold due to increased insecurity but mobile services have continued and reacted to displaced population needs.

Results

During the response, the number of cluster partners increased from three to 21 partners from 2012 to 2014 in Hodeidah and Hajjah. The scale up in nutrition service provision is reflected in the following results:

- OTP service: In Hodeidah, the OTP was expanded from 52 sites (end 2011) to 353 (early 2014), covering 94% of all fixed and temporary health facilities. In Hajjah, OTP sites increased from 82 sites (early 2012) to 177 (in 2014), representing 72% of all HF in Hajjah (fixed and temporary).

- Coverage of SAM treatment: Coverage surveys (Semi Quantitative Evaluation of Access and Coverage (SQUEAC)) were conducted in two districts in Hodeidah and two districts in Hajjah from 2013 to 2014, reporting point coverage of 49-64%. On average, this is above SPHERE standard for rural areas and has caused other governorates to adopt the CMAM model.

- Integrated services: Integration of inpatient TFCs and SCs into district-level HF increased from one (2011) to 10 (2014) in Hodeidah, while in Hajjah, the number increased from two in 2012 to three in 2014.

- MAM treatment: Supplementary feeding for children with MAM and pregnant and lactating mothers was increased in Hodeidah from four (early 2012) to 274 (end 2014) HF. In Hajjah, it increased from 11 (2012) to 121 (2014) HF providing services for MAM.

- Mobile teams: Mobile teams implementing integrated health and nutrition services increased from zero (2011) to 23 (2014) in Hodeidah and from three to 12 in Hajjah in the same time period.

- Staff capacity development: Community mobilisation efforts resulted in an increase in community health volunteers (CHVs) trained in nutrition from zero (2012) to 2297 (2014), increasing further to 1551 (2014) for Hajjah. Additionally, a total of 1,645 community leaders were sensitised in both Hodeidah and Hajjah.

- SAM enrolment and outcomes: In Hodeidah, SAM enrolment increased from 8,878 (2012) to 21,026 (2014). Cure rates, initially 41% (2012), increased to 70% by 2014, while default rates decreased from 54% (2012) to 26% (2014). In Hajjah, SAM enrolment increased from 3,748 (2012) to 10,216 (2014). Cure rates increased from 61% (2012) to 81% (2014) and default rates decreased from 35% (2012) to 15% (2014).

- IYCF: The number of breastfeeding corners in health facilities increased from zero (2012) to 60 (2014) in Hodeidah and from one to 34 in Hajjah during the same period.

- Monitoring: From 2010 to 2012, only 25% of OTPs delivered HO monthly reports on time in Hodeidah and Hajjah, many of which were incomplete. Additionally, 10% of OTPs had supply stock-outs due to irregular monitoring and unclear supply mechanisms. To address this, in 2013 UNICEF funded monitoring training and support (transport money, daily allowance) for 26 district and six zonal monitors in Hodeidah and 31 district and six zonal monitors in Hajjah. By early 2013, 90% of HF monthly reports were received on time and there was significant improvement in stock-outs as observed by the HO and UNICEF.

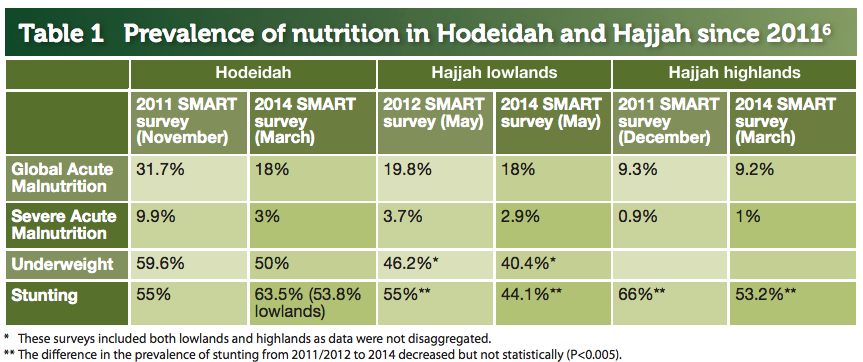

SMART surveys were conducted again in both Hodeida (March 2014) and Hajjah (May 2014) (see Table 1). The improvement in the nutrition situation in Hodeidah is attributed to the high coverage of nutrition interventions (64% in Jabal Ras district, May 2014), complemented by a range of multi-sectoral interventions. Absence of multi-sector interventions (lack of partner capacity) and the lower coverage of nutrition interventions explain less progress in Hajjah (49% in Aslem district, May 2014).

6 - All survey results are available online here.

Challenges from the 2012-2014 response

Integrated treatment and reporting of SAM and MAM

With different UN agencies providing support for SAM and MAM treatment, there was not always geographic overlap in service provision as UNICEF and WFP prioritise districts differently. WFP has expanded its target area based on advocacy from the nutrition sub-cluster, with ongoing cluster advocacy for further WFP expansion into UNICEF SAM treatment areas. Additionally, different reporting structures for treatment of MAM and SAM are used, with UNICEF providing support to district and zonal monitors and WFP providing support only at the governorate level. District-level monitoring has supported the development of a strong reporting system for SAM; reporting for MAM is less timely, specific and reliable.

Addressing stunting and prevention as part of emergency response

It was recognised that stunting was a problem in the situational analysis prior to 2012. The 2012-2014 SRP, whilst focused on CMAM scale up, included a community component (IYCF and peripheral health centre (PHC) interventions) to address the underlying causes of undernutrition. The community component was expanding with time, but increased insecurity has limited roll-out.

Funding

Lack of funds for the nutrition response in general remains a challenge and has resulted in areas with limited or no nutrition services.

2015 conflict

International NGOs pulled international staff out of Yemen in April 2015. The current crisis has affected all governorates more directly than in 2011-2014; currently three districts in Hajjah are experiencing intense fighting and all HF have closed down indefinitely. HFs in Hodeidah generally remain open, although access is security-dependent. In response to the escalation of conflict, the nutrition sub-cluster has shifted from development-orientation to a focus on emergency response. This is modelled on the 2012-2014 response across 23 sub-governorates, with increased use of MTs.

On-going operational challenges in 2015 include:

- A lack of clear figures of IDPs due to ongoing insecurity and related continual movement.

- Shortage of fuel has negatively impacted transport, delivery of supplies and implementation of mobile teams. In collaboration with other clusters, the Nutrition Cluster has advocated for and accessed alternative sources of fuel, including stock from private companies, government authorities, existing partners, the black market and renting vehicles already fuelled. UNICEF has procured additional RUTF supplies from Djibouti, delivered directly to Hodeidah by boat (all main airports destroyed in early 2015).

- Ongoing conflict has constrained access to affected and vulnerable communities. The conflict situation and supplies are monitored daily by HF staff, communicated to the HO by mobile phone and reports are hand-carried to the HO.

- Communications are largely conducted by mobile phone; coverage is limited in some areas. Electricity to charge mobile phones is also often scarce. Internet services are still available in Hodeidah and Hajjah but sporadic.

- Evacuation of international staff in April has meant remote mangement by international staff, resulting in delayed decision-making and reporting. LNGOs (30% of nutrition cluster partners in Hodeidah and Hajjah) have been involved in the response since 2012 and continue to play a critical role in service delivery, based on their expertise and capacity.

Learning

Yemen is a complex and challenging country that has achieved significant scale-up of nutrition services, particularly in treating acute malnutrition, despite increasing conflict and limited access. The following points of learning from this experience have been identified:

- Importance of local NGOs in service delivery. As has been shown in Yemen, international NGOs often have limited access in a crisis, with local NGOs able to provide more frontline and continuity of response. Mapping of, and investment in, LNGOs capacity is crtical from the outset to support and sustain implementation, and eventual transition of cluster activities.

- Importance of building local government capacity. While it can be challenging to build local government capacity, long-term impact can be significant. In the Yemen, successful government-led interventions have included the development of a cost-efficient mobile service delivery, and seen improved reporting and supplies management. Building capacity of local government in logistics and transport can facilitate future transition of services (and implementation in insecure areas).

- Integration of treatment and reporting for SAM and MAM. Geographic integration of MAM and SAM services remains low (25%), presenting a huge challenge for service delivery. While joint planning was conducted, shortage of funding (WFP) and different geographic areas of priority between UNICEF and WFP limit service overlap. Advocacy is required at all levels to ensure integration of service delivery, even if this means a ‘one agency/one programme approach’. Standardised reporting of both SAM and MAM programmes is useful and has been achieved through open discussion and flexibility of partners.

- Addressing stunting through prevention initiatives as part of emergency response. The high-stunting context of Yemen was recognised, but has not led to programming to directly address the problem. The high level of stunting in spite of decreased wasting in Hodeidah highlights the challenge of treating and preventing stunting in this kind of complex emergency.

- Multi-sectoral programming. The multi-sectoral response in Hodeidah contributed to s significant improvement in the nutrition situation, enabled by a strong National Nutrition Cluster Coordinator, continued advocacy across sectors at national and governorate level, and partner capacity.

- Engagement in the SUN Movement. NC engagement in the SUN movement is critical to ensure that emergency preparedness and response is part of the national multi-sectoral plan. This engagement should be institutionalised within the NC at national level. Additionally, it is apparent that intense conflict and political unrest can slow down progression of SUN processes, as evidenced by the lack of movement in endorsing SUN budget lines within the national budget.

Conclusions

Nutrition coordination in Yemen remains challenging, given the continued violence and insecurity that are restricting movement and programming. However, local government and agency staff are committed and working hard to implement nutrition services where security permits. The SUN multi-sector plan that covers both emergency preparedness and development initiatives offers a key platform around which to collaborate on improving nutrition outcomes for the people of Yemen.

For more information, contact: Dr. Saja Abdulla, Dr. Rasha, Dr. Rajia Sharhan.

References

1 International NGOs: International Medical Corps, Action Contra La Faim, Save the Children International, Mercy Corps. Local NGOs: Charitable Society for Social Welfare (CSSW), Soul Yemen. UN agencies (WFP, WHO, UNICEF) and the International Organisation on Migration.

IFPRI, 2014. 2014 Global Nutrition Report: Actions and Accountability to Accelerate the World’s Progress on Nutrition. International Food Policy Research Institute 2014, Washington DC.

UN OCHA 2015. Yemen Humanitarian Needs Overview, 2015 (Revised). UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. June 2015.

Also see: Global Nutrition Cluster knowledge management: process, learning