Save the Children’s IYCF-E Rapid Response in Croatia

By Isabelle Modigell, Christine Fernandes and Megan Gayford

By Isabelle Modigell, Christine Fernandes and Megan Gayford

Isabelle Modigell is the IYCF-E Adviser for the Technical Rapid Response Team (Tech RRT) at Save the Children. She has a public health background and has been involved in Save the Children’s humanitarian programming since 2012 in a variety of contexts and countries. From September – December 2015, she was the IYCF-E Programme Manager in Croatia.

Christine Fernandes is the Global IYCF-E Adviser for Save the Children UK. She has a background in maternal, infant and young child nutrition and has been working solely in humanitarian contexts (IYCF-E) since 2011. In September 2015, Christine deployed to Croatia to advise on the initial IYCF-E response and set-up.

Megan Gayford is the Senior Humanitarian Nutrition Advisor for the Save the Children UK and has been closely involved in the Europe response as the nutrition technical backstop for Save the Children. Prior to her relocation to London, Megan worked in country and regional level humanitarian nutrition roles for UNICEF, UNHCR and WFP.

Location: Croatia

What we know: Meeting the needs of infants and young children in transit populations is challenging due to limited contact time and unpredictable population movement and service needs.

What this article adds: In Spring 2015, Save the Children launched a frontline response to support infant and young child feeding (IYCF) as overwhelming numbers of migrants arrived at the Croatia/Serbian border. Initial mobile, reactive basic mother and baby areas evolved to include support in transit centres targeting breastfed (basic, rapid counselling) and formula-dependent infants up to 12 months of age (powdered and eventually ready to use infant formula (RUIF) supplies). Interim guidance on IYCF-E specific to this context was developed in October 2015 at global level due to an identified guidance gap which informed the response. Lack of coordination hampered IYCF response; it made it difficult to halt untargeted distribution of infant formula supplies, establish RUIF supplies, and ensure consistent, appropriate messaging and programmes. Complementary foods were dominated by donated, nutritionally limited supplies; UNICEF/NGO supplies were eventually established. Lessons learned include the importance of strong coordination, preparedness (e.g. stock and kit prepositioning, capacity mapping) and the need for clarity regarding target age for infant formula when in common use.

In the Spring of 2015, the number of refugees and migrants arriving in Europe began to unexpectedly and significantly increase. Many were Syrian refugees crossing the Mediterranean Sea from Turkey (alternative routes were riskier), routing from Greece, through Macedonia, Serbia and on to Northern and Western Europe. In mid-October, Hungary closed its borders with Serbia, redirecting flow towards Croatia’s Eastern borders. Within days, thousands of men, women, and children amassed in the ‘no man’s land’ between the borders of Serbia and Croatia. The majority of Croatian/Serbian border crossing points were rapidly closed off. Immigration police were completely unprepared for the sheer volume of people and their vast needs; border crossing points (that randomly opened and closed) were rapidly overwhelmed by arrivals of up to 8,000 people per day.

Programme context and challenges in Croatia

The SC team was mobilised and began to work as frontline responders within days of the first arrivals. It quickly became apparent that the immediate needs of infants and young children and their caregivers were physical first aid and protection, psychosocial support and IYCF support. Waiting times at the border were long – up to one day and often well into the night. Large crowds were exposed to sun, wind and rain resulting in heat stroke, heat exhaustion, fainting and hypothermia depending on weather conditions. In the larger border crossing areas, crowds blocked four lane highways, backing up kilometres of trucks into Serbia. Different border crossings opened and closed on a daily or half daily basis with no advance warning. Responding to needs required operating at different, ever-changing locations. The Save the Children (SC) teams relied on the same social media resources as the refugees, scanning Facebook and Twitter to find out which border points were open and where response was needed. In order to deliver timely and appropriate infant and young child feeding (IYCF) services in this context, SC needed to be highly mobile, able to rapidly set up, provide priority IYCF services and dismantle to be ready for the next location.

In the initial weeks of programming, mothers were evidently in distress and facing significant barriers to safely and adequately feed their children. Most were inappropriately dressed for the wind, rain and eventual snow, having either lost their belongings along the journey or having left home unprepared. Volunteers threw water bottles into crowds and handed out infant formula. Mothers were observed feeding cows’ milk to infants under six months of age, not measuring the quantities of water and powdered formula to prepare a feed and using dirty feeding bottles.

Long hours of waiting in the heat or cold without any information often resulted in tensions and occasional violence and injuries – with teargas being deployed on one occasion. Exhausted mothers stood in the jostling crowds holding often wet, cold, and dirty children in one arm while balancing their belongings in the other. Privacy was non-existent, making breastfeeding an uncomfortable experience. Women minimised their fluid intake as there were initially no toilets at the border crossings. Combined with severe stress, exhaustion, constant movement and a lack of support, SC was concerned that mothers were breastfeeding less frequently and for shorter durations. Many mothers were observed both breastfeeding and formula feeding their infants (also found in assessments in Serbia (UNICEF, November 2015) and Greece (SC, Feb, 2016).

The initial Save the Children response

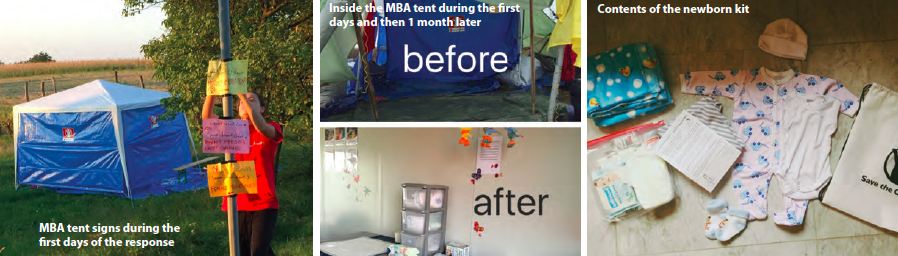

SC responded by providing basic, temporary Mother & Baby Areas (MBAs). These tents, stocked with practical supplies1 such as baby clothing, drinking water, cups and cleaning equipment, provided some respite for parents and children, a sheltered area to change their infant’s clothes, and privacy to breastfeed. Skilled IYCF counsellors and sufficient translators were not initially available so the focus was to meet basic needs and create an enabling environment to allow mothers to feed and care for their children. During this early phase, there was no provision of infant formula supplies. Mobility, changing locations on a half daily basis and operating 24/7 was unique to SC’s Croatia response during the first phase. Mobile MBAs (using vans and cars) allowed IYCF teams to respond to hotspots. Throughout the day and night, we provided reassurance when possible and assisted those who became unwell. A big part of the initial response involved going through the crowds with water, paper and crayons to help identify waiting children and invite their families to a place away from the crowds. In order to take them to the MBA, special permission was needed from the police every time. Our response was made possible through strong, interagency collaboration, particularly with UNHCR, MSF, and the Croatian Red Cross. For example, SC often set up the MBA near the UNHCR screening point for vulnerabilities or near MSF’s treatment area, because our target population naturally congregated in these areas and for ease of referral.

Initially it was unclear what Croatia’s government response would be. However, within days, people arriving were transported to the rapidly set up Opatovac Transit Centre. SC’s focus became divided between responding to informal settlements at the border and setting up IYCF in emergencies (IYCF-E) services within the transit camp.

Second phase of response

SC began to establish an IYCF-E programme targeted at infants (0 – 12 months) and young children (12 – 24 months) and their caregivers that focused on:

-

Protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding

-

Identifying, protecting and supporting infant formula dependent infants

-

Managing the sourcing and provision of infant formula to ensure the needs of both breastfed and non-breastfed infants were protected and met

-

Securing access to nutritionally safe and adequate complementary foods for children 6 – 24 months

Our first action in Opatovac was to engage with medical service providers and the Croatian Red Cross to halt the untargeted distribution of infant formula. In collaboration with UNICEF and Croatian organisations, a simple MBA was rapidly set up in a 20 foot shipping container. Space constraints were a major challenge. Temperatures had dropped drastically and doctors reported that up to half of the babies had worryingly low body temperatures; thus the MBA offered a heated place for caregivers to change their babies as well as a private space to breastfeed. Caregivers requesting infant formula were referred to the nearby paediatric services, which had been agreed upon as the sole distribution point. Here, a medical non-governmental organisation (NGO), provided powdered infant formula and basic bottle cleaning for one-time feeds (refilling bottles). The provision was very donation dependent and not Code compliant. Later, the NGO decided to distribute new bottles and pacifiers.

Management of Breast Milk Substitutes (BMS)

Requests for infant formula were extremely common. Approximately half of the population were from Syria, with smaller numbers from Afghanistan, Iraq and other countries. With the introduction of selective entry procedures mid-November 2015, only persons from these three countries were granted entry into Croatia. Pre-crisis data from Syria showed low exclusive breastfeeding rates (43% of infants under 6 months) and low continued breastfeeding rates (23% at 2 years) (UNICEF State of the World’s Children Report, 2012).

Despite initial success in halting untargeted distribution of infant formula, it remained a challenge to convince other actors to not distribute untargeted infant formula, bottles and pacifiers. A vast variety of powdered infant formula (PIF) was initially provided without any accompanying counselling or equipment to support hygienic preparation. Sanitation was often poor and access to boiled water very limited, resulting in incorrect and unsafe formula preparation. The response was largely staffed by first time volunteers from all over Europe with very high turnover. Health providers were particularly difficult to convince to follow WHO protocols, wanting more evidence/data/research on the risks associated with infant formula in this context. Volunteers had less knowledge but responded well to advocacy and were more willing to change their actions. Advocacy with one NGO led to their employing rapid screening before provision of infant formula. We advocated to Red Cross camp management to better monitor the distributions, but due to high staff turnover, this was difficult to sustain. SC recognised the need for targeted infant formula supplies and opted to procure Ready to Use Infant Formula (RUIF), as a less risky (it is a sterile product until opened and does not require reconstitution with water) though more costly option (RUIF is roughly 2.5 times the cost of PIF). It took three months to secure a supply was procured from a manufacturer in-country and relabelled by SC in Arabic, Farsi and English. No supplies were available via UN agencies.

SC was the only actor present with IYCF-E expertise on the ground, however several other actors were involved in BMS management. Whilst the establishment of an IYCF technical working group (TWG) in early December 2015 helped to generate some consensus and standards, it lacked authority; the absence of a formal humanitarian coordination system meant leadership and accountability were lacking. Having RUIF supplies strengthened SC’s advocacy position as it offered a safer alternative for formula dependant infants. In addition, SC along with key partners, were drafting interim guidance on IYCF for transit populations2, which helped to coordinate and agree upon protocols for IYCF programming.

Complementary feeding

The initial humanitarian response did not source supplies of complementary foods and no dairy products were allowed inside the camps by the MOH in the first and second phases, especially during the time of rapid processing. When the borders closed, partners began distributing cow’s milk for older children and subsequently, some people were allowed to purchase milk at the supermarket/shop outside the Transit Centre. There was a significant lack of suitable and adequate complementary foods along the migration route; commercial baby foods were most common, mainly protein-poor pureed fruit and vegetables. Many violated the Code (e.g. labelled as suitable for infants aged 4 months and above; not in appropriate language) and families were concerned that meat containing products were not halal or contained pork. Much was abandoned and discarded. There were vast quantities of donated commercial baby foods that were widely distributed. At one point, a well-known supplier of baby foods pushed to donate 5.5 metric tonnes of jarred baby foods nearing their expiry date.

Around December 2015, UNICEF and a medical NGO began distributing complementary food packages for age groups 6-9m, 9-12m, and 12-36 months. Each contained two sachets of Plumpy'Sup, two jars of commercial baby food (one fruit based, the other animal protein based), a biscuit for the 12-36 month group, baby wipes and plastic spoons. The Red Cross general food distributions included apples and oranges. There was no micronutrient supplementation. SC investigated relabelling baby food jars but this proved too costly and time consuming.

Until safe, acceptable and nutritionally adequate foods that could be consumed on the move were identified, it was agreed by the TWG to provide infant formula for non-breastfed infants up to 12 months of age. Caregivers were counselled on complementary feeding for children 6 – 24 months focused on what foods were available and how to manage on their onward journey. For breastfed infants, continued breastfeeding was strongly encouraged. Sometimes donated baby foods were used with information on their limitations. Caregivers were quick to dismiss the unfamiliar products provided in the UNICEF/Manga packages, but were encouraged to use them in the absence of alternatives (children were observed to accept them well). There was very limited contact time so counselling was focused on addressing immediately relevant, practical issues.

Challenges of IYCF-E in a transit setting

Minimal contact time

The government’s approach to minimise transit times hindered humanitarian assistance and meant many could not access needed support or rest. Caregivers were often exhausted and highly stressed by the constant movement, compromising their abilities to care for their children or process information. The fast moving pace also meant families were concerned about becoming separated, for example by a visit to health services or the MBA. We addressed this by coming to an agreement with the police to allow the remainder of the family to stay in a waiting area we installed. However, the high turnover of different police units and fluidity of the situation meant these agreements had to be repeated on an almost daily basis.

During the short stay in the transit camp, caregivers had multiple needs to address in a very limited time – including food, hygiene, changing their baby’s clothing and diapers, charging phones and sometimes seeking reunification with separated family members. Stress levels were often further exacerbated by the acute lack of information on when they would leave and what would happen next. As a result, caregivers tended to be very rushed and focused on leaving. Counsellors reassured caregivers that families would not become separated or miss the next train or bus if they stayed in the MBA, and facilitated access to other services. Efforts were made to create a calming and comfortable environment in the MBA. All staff were trained on Psychological First Aid and SC’s psychologist was also on hand for those requiring additional support. SC developed kits to provide the essentials quickly; newborn kits, breastfeeding kits, and Ready to Use Infant Formula (RUIF) kits were targeted.

In the first phases of the response, SC’s counselling capacity was also limited by cultural and language barriers. SC eventually recruited and trained national Croatian staff to deliver IYCF counselling through translators who also required sensitisation on IYCF-E and counselling skills. However, translators, particularly female, were in short supply and high demand. Only a small number of national breastfeeding promotion organisations exist in Croatia, so we recruited women with strong interpersonal skills and built their IYCF counselling capacity.

Cup feeding

The promotion of cup feeding posed another such challenge given the context. Cup feeding is preferred over bottle feeding because it carries less risk of diarrhoea and other infections in unsanitary environments, as well as increasing bonding and not interfering with breastfeeding (WHO, UNICEF). However, this was a new concept for many and not readily accepted by stressed caregivers, bombarded by a multitude of different information and supplies. Support for transition to cup-feeding was made more difficult by the lack of contact time. If caregivers had run out of formula, as they often had, babies arrived hungry and crying. The provision of bottles and teats by other actors further undermined efforts. Despite these significant challenges, some caregivers readily accepted to try cup feeding (particularly mothers of older infants) and some babies easily adopted the practice; in our view, this made our efforts worthwhile. Showing photos or videos of other babies who are cup feeding successfully was very convincing for parents. Many mothers were already well aware of the need for good hygiene – the context simply did not allow them to practice it. When we explained that they could have as many clean cups as they needed, some gladly accepted the offer. Since more infant formula may be spilled during cup feeding when done on the move, adequate supplies of RUIF, plastic bibs (children usually just had one set of clothes) and cups with lids were provided.

Our teams explored cup feeding as a first option whenever possible. However, when the situation did not allow (either due to caregiver refusal or the setting) we also offered bottle sterilisation services; a BMS Management Area, separate from the MBA, was equipped with cleaning equipment that included sterilisers and kettles. While bottle feeding was culturally accepted and has practical advantages in transit, we considered the potential risks of unsterilised bottle feeding (e.g. increased diarrhoea due to poor hygiene) to outweigh the challenges of cup feeding. There were diarrhoeal outbreaks but requests for official data from partners were unsuccessful which meant it was not possible to establish if diarrhoea was related to feeding mode. It is possible that given a more coordinated and standardised response, where only cups were distributed rather than bottles, there may have been more acceptance of cup feeding.

A shift in strategy: return to rapid processing

In early November 2015, the Croatian authorities closed the Opatovac Transit Centre and SC’s operations were shifted to the Winter Reception and Transit Centre (WRTC) in Slavonski Brod. About a month later, further transit developments saw a return to rapid processing and registration of large waves of people. As a result, people no longer entered the sectors in which the MBAs were located and contact opportunities shrunk. The programme thus refocused on meeting basic needs and transmitting key IYCF messages - this time through the distribution of breastfeeding shawls (for privacy) and baby kits which contained hygiene and clothing items, as well as leaflets in English, Arabic, and Farsi. Infant formula was still provided by SC to those identified (only rapid assessment and counselling was possible): RUIF kits provide formula supply, cups with lids, soap, bib, instruction leaflet and key messages in various languages. Manga continued to provide PIF.

Key learning from the response and next steps

Supporting IYCF requires effective cross border and regional coordination of actors implementing IYCF-E. Our experiences reflect a lack of consistency and standardisation to help caregivers practice safer feeding options, which compromised what could be achieved in terms of minimising risk and supporting safer practices. Caregivers were often tired and confused by the multitude of different actors providing varying messages, IEC materials and products using diverse approaches. Given the severe constraints, the SC approach to counselling was to accept the feeding behaviours of mothers but advise them on how to manage and minimise risks. An effective behaviour change intervention requires consistent messaging over time. This is incredibly challenging in a quick moving population, on different routes and moving across borders to different service providers who are not clearly linked through a referral system up to the final destination.

Coordination in this regional crisis has proved complex, further complicated by political factors, different government priorities and gaps in leadership and technical capacity. This has contributed to slower linkages of services. The diversity of actors, many of which are volunteer groups following different protocols and standards, has added to this complexity in coordination and standardisation of services.

BMS management in non-breast fed infants aged 6-12 months. Whilst there is a clear nutritional need to provide infant formula for non-breastfed infants under 6 months of age, options for suitable feeding support for the non-breastfed child aged 6 to 12 months in transit require further examination. Relactation was not a viable option in this transit context. The prohibited distribution of dairy products by the MOH in phases 1 and 2 meant using cows’ milk in non-breastfed infants over 6 months was not an option. While the lack of adequate complementary foods were the main reason for the decision to provide infant formula up to 1 year, we also considered the stress we would impose on caregivers by refusing to provide formula without having the time to provide an explanation or another suitable food.

Prepositioning of MBA kits and RUIF. Sourcing and replenishing MBA equipment was hugely time consuming during set-up; prepositioned basic kits would have enabled faster response. In addition, adequate supplies of generic (unbranded) RUIF proved extremely difficult to source both locally and internationally; importing stock risked logistical delays. Branded supplies were eventually sourced and relabelled by SC; this proved costly and also raised issues over liability regarding the integrity of label translations. SC has begun to identify and vet regional RUIF suppliers for better preparedness. Lack of a viable UN supply source, as recommended in the Operational Guidance on IFE, hampered responsiveness.

IYCF/IYCF-E Capacity in Europe. The skill-set required for immediate IYCF-E support in Croatia and along the route was very specific: fully trained in IYCF counselling, female, Arabic or Farsi speaking. It would have helped to have mapped existing IYCF actors in the region prior to the emergency. Over time, SC have been able to connect with national stakeholders and breastfeeding organisations, and have now developed a list of local resources to draw upon for a more rapid response.

For more information, contact: Christine Fernandes, tel: +254 (0) 787 777 741.

Experiences of implementing the ‘Interim Operational Considerations for the feeding support of Infants and Young Children under 2 years of age in refugee and migrant transit settings in Europe’ are currently being sought by the IYCF-E Technical Discussion Group; a collective of agencies directly involved in the operations in Europe and ENN (representing the IFE Core Group). An online survey is available here.

References

1 MBA specification: 9m2 gazebo with sides, a picnic table, collapsible seating, a handwashing station, lighting, and cleaning equipment. Stocks: nappy changing supplies, warm baby clothing and blankets, disposable raincoats, stationary, drinking water, cups and hygiene supplies

2 Interim Operational Considerations for the feeding support of Infants and Young Children under 2 years of age in refugee and migrant transit settings in Europe. Version 1.0, October 2015.