CMAM scale-up: experience from Ethiopia’s El Niño response 2016

By Christoph Andert, Zeine Muzeiyn, Hatty Barthorp and Sinead O’Mahony

Christoph Andert is a Nutrition Advisor at GOAL’s HQ. For the past 12 years he has worked mainly on emergency nutrition, including CMAM, IYCF and M&E systems in Africa and Asia.

Zeine Muzeiyn has worked in nutrition for the last 11 years. Before he joined GOAL Ethiopia, he worked with Concern Worldwide in West Darfur, Sudan and has extensive field experience. Currently he is Head of Nutrition for GOAL Ethiopia, leading the CMAM response.

Hatty Barthorp is a Global Nutrition Advisor at GOAL’s HQ. She has been working on emergency, transitional and development programmes for 14 years.

Sinead O’Mahony is a Nutrition Advisor at GOAL’s HQ. She has both a research and an operational background and been working in the field of health, research and humanitarian aid for seven years.

The authors extend thanks to the whole GOAL Ethiopia team who helped make this scale-up happen. Further thanks to the Ethiopia Ministry of Health, the Emergency Nutrition Coordination Unit and GOAL’s sub-grantees. Finally, GOAL gratefully acknowledges OFDA, as well as Irish Aid, ECHO and UNOCHA, for funding the CMAM scale-up in Ethiopia.

Location: Ethiopia

What we know: Periodic severe food insecurity and consequent surge in acute malnutrition prevalence persists in Ethiopia. An early warning system operates at district level to trigger response.

What this article adds: In 2015, half of Ethiopia’s districts (woreda) were classified as hotspots, requiring acute malnutrition treatment intervention. In response, GOAL scaled up operational support to the Ministry of Health from 22 woredas (862 health facilities within inpatient/outpatient treatment services) to 70 woredas (1,900 health facilities covered) over eight months. National authorities played a key lead role in identifying needs and coordinating response. GOAL applied its established model of minimalist technical and operational support, coupled with redeployment of experienced staff to new woredas and positioning of recently trained staff to established facilities. Challenges related to human resources, logistics, coordination, funding and supply pipelines were largely overcome. A Quality Assurance Framework was developed to address service-quality issues identified in the initial phase of scale-up. Key to successful scale-up were robust early warning data and situational analysis, well coordinated response, flexible donor funding, established systems, services and capacity, and experienced in-country NGOs who could respond quickly and innovatively.

Introduction

Food insecurity is a persistent feature of the humanitarian landscape in Ethiopia, with recurrent nutrition emergencies every couple of years over the last decades. The latest one, considered by some the most severe since the 1984 famine, resulted from two consecutive crop failures1 in 2015, triggered by the El Niño phenomenon, that decreased overall crop production by 50-90%. Initial government estimates of people in need of emergency food assistance for 2016 were set at 4.5 million in August 2015 but were revised to 8.2 million two months later, and finally to 10.2 million by the end of 2015. Updated figures in mid-2016 estimated 9.7 million people were still in need. Acute malnutrition increased countrywide, with more than half (443) of all districts (known as ‘woredas’ in Ethiopia) being classified as hotspot woreda2 (Priority 1 to 3) by March 2016, which would trigger selective feeding interventions. This was the highest number of woredas classified as hotspot since 2009. In total, 420,000 children under 5 years of age with severe acute malnutrition (SAM) and 2.5 million children with moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) were expected to require treatment in 2016.

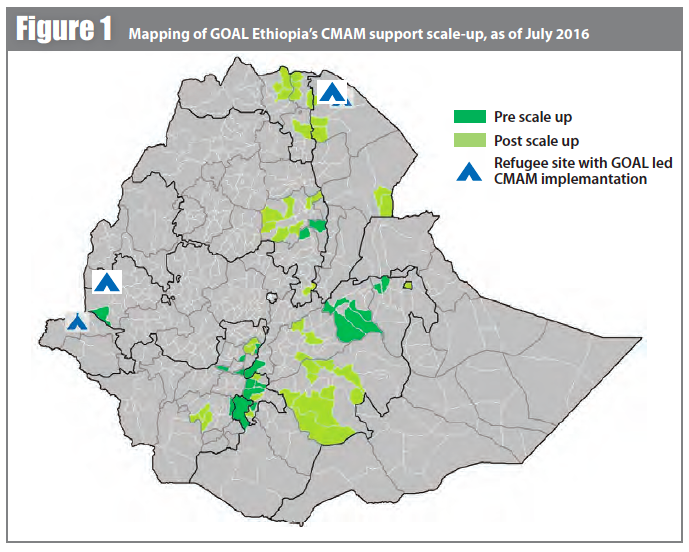

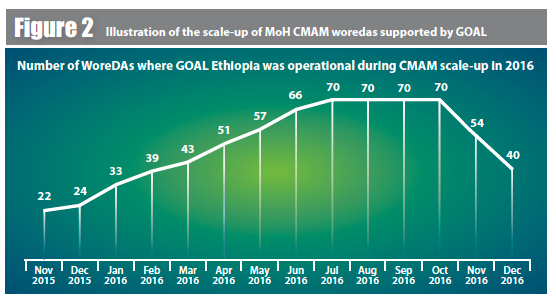

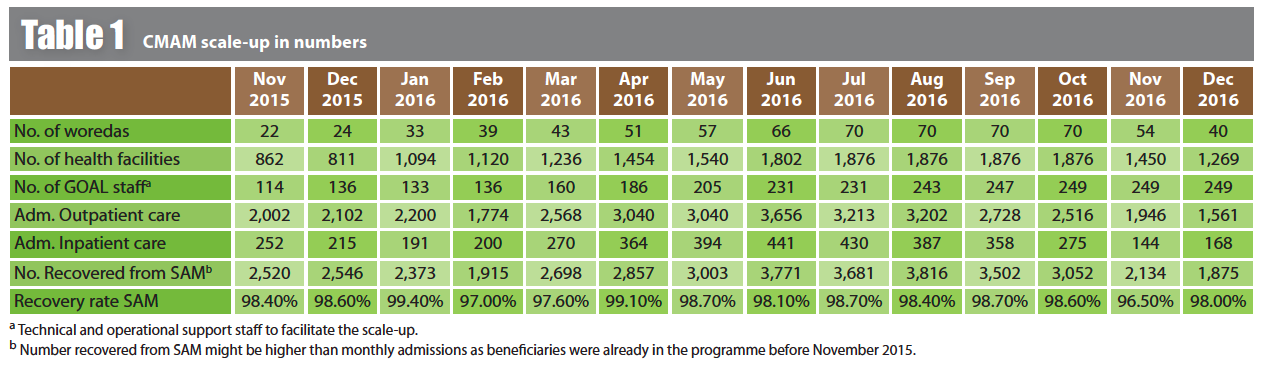

In November 2015, GOAL Ethiopia was operational in 22 woredas, supporting the Ministry of Health (MoH) to provide community-based treatment of acute malnutrition (CMAM) services across approximately 862 health facilities with inpatient and outpatient therapeutic care. A rapid scale-up increased GOAL’s operational support to 70 woredas by July 2016 with around 1,900 health facilities covered – the biggest ever number supported for CMAM by GOAL in Ethiopia (see Figures 1 and 2). With this, GOAL covered 15.8% (70 out of 443) of all hotspot-classified woredas in Ethiopia in 2016. This scale-up led to several operational and service-quality challenges, solutions and lessons learnt.

GOAL’s CMAM support model for Ethiopia

GOAL started nutrition programming during the 1984 famine in Ethiopia. The CMAM approach (formerly called Community Therapeutic Care (CTC)) was first used by GOAL in Ethiopia in 2005. Programming has since evolved from direct international non-governmental organisation (INGO) implementation to support of government staff to run CMAM in MoH health facilities.

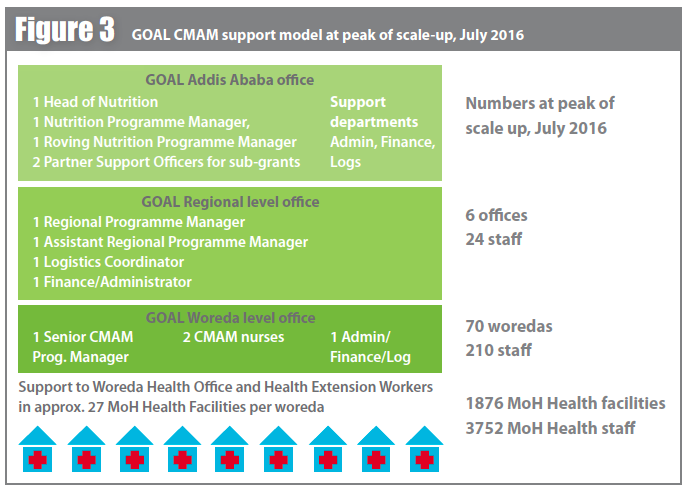

With this support model, GOAL typically sets up a woreda field office and provides three technical staff (one Senior CMAM Programme Manager and two CMAM nurses) and several support staff (one administrator/finance/logistics staff, four guards, one cleaner and drivers) per woreda to facilitate operations. Technical staff provide mentoring and on-the-job training to the government health staff in hospitals, health centres and health posts, as well as to facility-based health extension workers (HEWs) and health workers (HWs) in that woreda, to run CMAM services for acutely malnourished children. Drugs and ready-to-use therapeutic foods (RUTF) are supplied to the MoH by UNICEF. Movement plans are coordinated so that technical staff visit all health facilities (usually around 30 in each woreda), timed with Outpatient Therapeutic Programme (OTP) follow-up days, and conduct monthly joint monitoring visits with the woreda health office to specific sites. A checklist is used to assess in-service technical ability of MoH health facility staff on anthropometric measurements, admission and discharge criteria, medical treatment and M&E, as well as staff attendance, stock management and general management. This checklist is used to monitor treatment quality and score health facilities; results are used to prioritise certain facilities for more frequent visits. GOAL’s woreda field offices are supported by regional offices with one Regional Programme Manager, one Assistant Regional Programme Manager, one Logistics Coordinator and one Finance/Administrator in each office. At head office in Addis Ababa, the nutrition team is led by the Nutrition Coordinator, who oversees a team of four staff: one Nutrition Programme Manager, one Roving Nutrition Programme Manager and two Partner Support Officers for sub-grants. Using this model, GOAL would usually support MoH-led CMAM in around 22 woredas (approx. 862 health facilities), involving 66 woreda-level technical staff in any given year. An exit strategy for every supported woreda exists whereby GOAL stay for 9-12 months before rotating to a new site that requires capacity-building support.

Scale-up process

Operationally, the scale-up progressed in a very organised fashion over a timeframe of eight months. Flexible funding3 in most part from OFDA and to a lesser degree from Irish Aid, ECHO and UN OCHA allowed GOAL to intervene in any upcoming hotspot Priority 1 woreda. The Emergency Nutrition Coordination Unit (ENCU)4 invited actors to cover any newly identified hotspot Priority 1 woreda unsupported by an NGO partner. In general, the National Disaster Risk Management Commission (NDRMC), jointly with Federal-ENCU, play the key role in monitoring the food security and nutrition situation in Ethiopia and coordinating actors for an organised humanitarian response based on the woreda hotspot classification. Newly identified and assigned woredas by the ENCU were pre-assessed by GOAL’s roving nutrition technical staff from the country office in Addis Ababa. Support needs and gaps were identified and necessary agreements and permissions for GOAL to support the MoH for CMAM were arranged. All information was documented in woreda assessment reports to guide the setup of the operation. A new field office was then established by GOAL’s logistics team once agreements have been signed. Local properties rented in the woreda centre included office space for technical and support staff and living space for relocated or newly hired GOAL staff, as well as storage space for corn-soya blend (CSB)/oil and RUTF.

Prior to the 2015-16 scale-up, GOAL operated a CMAM Trainee Nurse programme; on graduation, clinical staff undertook a two-week, theory-based induction and condensed training at head office. Thereafter they were given on-the-job training at woreda level by a senior nurse for six months. This system worked well for a number of years, providing a qualified cadre of staff for CMAM support programming. During the scale-up itself, adequate staffing was achieved by relocating long-standing and experienced GOAL CMAM support staff from the 22 existing woredas supported by GOAL to new woredas. Support would be led in new woredas by one experienced CMAM staff (normally the Senior CMAM Programme Manager) accompanied by a newly recruited CMAM trainee. Gaps left by these relocations in the 22 pre-existing woredas were filled through the promotion of the best-performing and most experienced CMAM nurses to woreda programme manager positions, and newly recruited nurses who had completed the six month trainee programme were brought in to fill CMAM nurse roles. All new woredas were pre-assessed by roving nutrition programme managers to identify support needs and gaps and arrange the necessary agreements/permissions for GOAL to support the MoH for CMAM. Upon signature of agreements, a new field office was established and support operations commenced.

In line with the huge increase in the number of field-level support sites, GOAL Ethiopia also significantly increased its technical and operational support staff at regional and country office levels (see Figure 3). Six regional offices were established and staffed with Regional Programme Managers, Assistant Regional Programme Managers, and coordinators for Human Resources (HR), finance and logistics. These staff were tasked with facilitating and monitoring the quality of the humanitarian service delivery at woreda level. At country-office level, operations and systems departments also added new staff, including Programme support officer, Partner support officer and Roving nutrition programme manager, while HR, finance and logistics also increased their roving teams to support the scale-up operation. With this, GOAL Ethiopia increased its total staff by 218% from November 2015 until October 2016.

Challenges

In eight months from November 2015 to July 2016, GOAL Ethiopia tripled the number of CMAM-supported woredas. MoH SAM admissions peaked at 4,097 in June 2016, compared with 2,768 SAM admissions for the same month the previous year. Despite detailed implementation plans being designed, this scale-up brought to light several challenges and lessons learnt for the GOAL nutrition team.

Operational challenges

Human Resources Tripling the number of woredas supported also means tripling the number of GOAL staff to cover new operational areas. GOAL’s existing CMAM support operation in 22 woredas allowed it to relocate experienced CMAM staff to new woredas quickly. Gaps were filled through the CMAM Trainee Nurse programme (described above). As this rapidly proved successful, the model was adopted by other NGOs, including GOAL Ethiopia’s five sub-grantees, improving the human resources pool for the emergency response.

Logistics

A significant challenge encountered by the logistics team during the rapid scale-up was ensuring the right products and services were available in the right place at the right time. Procurement of basic materials to ensure all health facilities were adequately stocked in new woredas increased massively, requiring modifications to be made to ‘normal’ procurement procedures to enable more responsive and speedy actions to be taken. This included the use of waivers5 when deemed acceptable and pre-positioning of CMAM start-up kits in strategic locations, thus eliminating previous procurement lead times of two months plus. With the government restrictions on purchase of new vehicles in Ethiopia, GOAL used rental cars for all newly covered woredas. A shortage of both rental cars and rental companies willing to rent out cars to remote regions of the country made it difficult to cover all transport needs of the scale-up operation. To overcome this problem, GOAL Ethiopia reassigned its own vehicles to areas where rental companies did not want to go.

Pipeline

As pipeline ruptures are frequent and to a certain degree predictable during the initial phase of an emergency, GOAL decided to purchase and preposition various MAM and SAM treatment commodities at woreda level in strategic sites. Consequently, GOAL was able to help the MoH avert serious problems when trying to manage the influx of acutely malnourished cases by ensuring that essential drugs were available, basic material provisions could be accessed, and adequate hygiene-sanitation could be ensured. If this had not been the case, morbidity and mortality rates would undoubtedly have risen.

Coordination

During the course of 2016, the ENCU was faced with a critical gap in the absence of an in-country ‘cluster coordinator’ overseeing the response. Consequently, GOAL filled this position temporarily within the ENCU for November 2015 until a permanent replacement was identified. This demonstrates the versatility and utility that NGOs can provide, especially during times of stress. In spite of GOAL’s efforts, additional coordination staff were and are still needed at national level to help direct coordinated and effective emergency responses. At a decentralised level, however, particular regions, including Amhara and Oromia, demonstrated very strong coordination across the regions and between zones. GOAL also found that actively participating in technical working groups proved extremely useful in terms of contributing to positive developments in guideline approaches, such as reducing screening timeframes for activities carried out by HEWs from monthly to weekly.

Funding

Donors proved agile and were able to respond in a timely fashion, largely due to the significant efforts employed by the Government of Ethiopia to collect, collate and analyse early warning information, resulting in an accurate, anticipated prediction of the size and scale of the emergency. Due to longstanding relationships GOAL has with many donors in Ethiopia, we were able to readily access funding to deliver a rapid CMAM scale-up in line with plans. Donors recognised GOAL’s capacity for rapid response and, in addition to increased CMAM support, were also able to provide funds for some supportive nutrition-sensitive activities, including WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene) for CMAM and emergency seeds for CMAM beneficiaries. Unfortunately, despite attempts, GOAL was unable to find funding for other nutrition-sensitive activities that would have significantly improved morbidity outcomes, such as the management of epidemics, including scabies and diarrhoeal outbreaks.

Challenges with service quality

Over the last ten years, GOAL has refined a minimalist support approach appropriate for Ethiopia, delivered through two to three core technical individuals in each woreda. Therefore, GOAL fully realised that reducing the number of experienced staff per woreda, in conjunction with the hugely elevated caseloads, would inevitably result in challenges to ensure that service quality was maintained. Box 1 below highlights some of the challenges the teams faced during the first couple of months of support.

Box 1: Service quality issues identified by GOAL

- The time required to address administrative issues by Senior CMAM Programme Managers at the outset of the support period within a new woreda was significant, meaning time available to provide technical guidance for newly recruited and trained nurses had to be compressed.

- On initial review, infrastructure services in new support woredas were often deemed sub-standard, thus time had to be allocated to improve these (for example, the hygiene and sanitation of kitchen areas of in-patient sites).

- At the outset of the support period, GOAL was often challenged by woredas not having the requisite materials and supplies to deliver adequate care, such as measuring jugs, powder scoops for milk feeds, poor quality/lack of MUAC tapes and inadequate buffer stocks of therapeutic milks and RUTF at health-facility level.

- Incorrect anthropometric measurements being taken/recorded.

- Inappropriate resource allocations within woredas, i.e. sites with low inpatient caseloads sometimes had numerous feeding kits.

- Despite Ethiopia including nutrition in clinical and nursing pre-service training packages, some MoH medical staff were identified as still not having received training on inpatient care.

Quality Assurance Framework

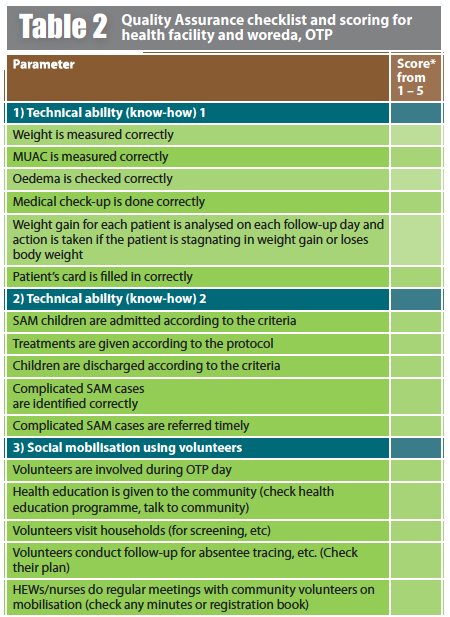

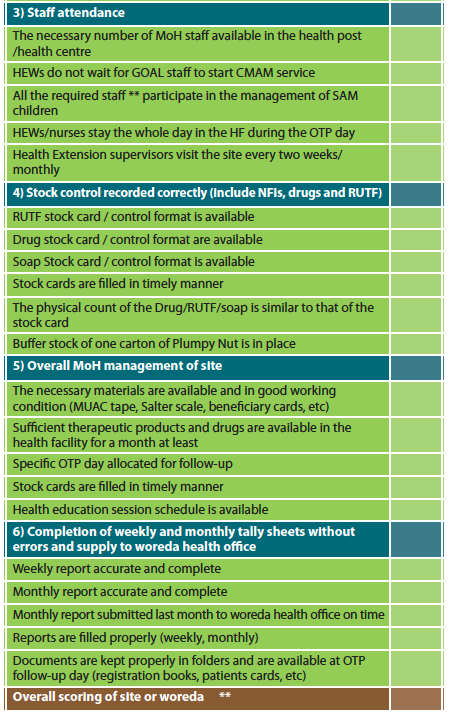

In light of the issues identified during the initial phase of the scale-up, GOAL Ethiopia put a more stringent and detailed Quality Assurance Framework (QAF) in place to govern the quality of the emergency nutrition response and ensure quality was not compromised by scale. The framework consisted of an updated quality assurance checklist and a dashboard summarising quality scores for each health facility and woreda. The checklist (observational data) is used by the CMAM nurses and the Senior CMAM Programme Manager (woreda-based staff) for monitoring health facilities running therapeutic services. Bi-monthly meetings at national level were conducted to discuss dashboard results and schedule support visits for woredas that scored low in quality (any score below 2.0 was considered low, see Table 2 outlining the checklist for OTPs). Scale-up to new woredas was temporarily suspended for a three-week period in April/May 2016 to provide adequate time for senior technical staff to undertake warranted support visits and embed this process. In light of GOAL flagging specific issues, in conjunction with high-level GOAL technical support, regional and woreda technical staff also increased targeted supervision, having the combined and desired effect of perceptibly increasing service quality.

* Scoring is done for each parameter on a scale from 1 to 5 (1=poor, 2=fair, 3=good, 4=very good, 5=excellent) for each health facility. Woreda scoring summarises all the health facility scores in one woreda, thus poorly performing health facilities and woredas could be identified for increased on-the-job training and mentoring going forward.

** Overall scoring is done by summing individual scores and divide them by 36.

*** Specifically two HEWs (two HEWs always runs a health post/centre)

Conclusions

To enable GOAL to more than triple the level of support in a matter of months, adequate forewarning of the impending situation was critical. Rigorous data collection and analysis by the Government ensured that donors and support partners alike were well aware of the deteriorating situation and the impending crisis that unfurled during 2016, months in advance.

Consequently, adequate funds could be mobilised by key donors and NGOs, including GOAL and its partners, who were therefore able to respond to many of the hotspot classification 1 woredas in a timely manner, ensuring that the substantial increase in caseload did not significantly lead to a decline in service provision. Thus GOAL has demonstrated that a rapid scale-up of NGO support to the MoH to provide quality CMAM care in a short timeframe, in acute emergency contexts, is feasible.

Although logistical, pipeline, coordination and funding challenges were encountered, working solutions were identified to overcome most issues effectively. Two issues warrant flagging. First, there is a human resources issue that should be addressed differently in prospective emergency-support programming by adding an additional, non-technical GOAL support person per woreda team, tasked with overseeing the raft of administrative issues that need addressing during the initial months of support. This would free up GOAL technical staff to focus exclusively on strategic support to both field and clinical/facility-based MoH staff. Second, GOAL should continue to request that donors seriously consider funding parallel nutrition-sensitive activities during this type of emergency, such as managing concurrent disease outbreaks, that are intrinsically linked to nutrition outcomes.

GOAL recognises that an INGO-led response, albeit using a skeleton staff structure so as not to undermine existing operations, is not a sustainable model, given the cyclical and thus largely predictable nature of emergencies in Ethiopia.

The CMAM support provided by GOAL and direct partners (sub-grantees) in both emergency and non-emergency periods is focused around capacity-building, in-service training and working to improve data management, supply chains etc. These are all targeted at improving the quality of MoH service provision, both at facility and community level. This is a reasonably sustainable model, although it is dependent to some degree on staff turnover, but it does not build any long-lasting government capacity to respond to emergencies. GOAL has therefore been in discussion with the Government of Ethiopia and donors over the past two years concerning the potential for collaboration with the MoH to build a rapid-response capacity which would transition away from an INGO-led response. Two CMAM-focused concepts have been proposed by GOAL.

The first focuses on a systems-strengthening approach to emergency nutrition response. The second focuses more on building capacity of the MoH to address coverage issues for treatment of acute malnutrition. This would appear to be the next logical and progressive step for the MoH to take greater responsibility for CMAM in predictable, chronic emergencies.

In this respect, it should be noted that ‘rapid response’ in general is already listed in the Health Sector Transformation Plan under Strategic Initiatives: “…developing a national health emergency workforce with the right skill mix to enhance standing and surge capacity of the country to respond to emergencies…” (MoH, 2015) and is thus a key aim for the Ministry until 2020.

For more information, contact: Hatty Barthorp, email: hbarthrop@goal.ie

References

MoH, 2015. Health Sector Transformation Plan (HSTP) 2015/16-2019/20. The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health, Oct 2015 p84. www.globalfinancingfacility.org/sites/gff_new/files/documents/HSTP Ethiopia.pdf

Footnotes

1Including the Kremt (long) rains, which normally feed 80-85% of the country.

2Hotspot woreda classification has been derived using multi-sector indicators, including health and nutrition, agriculture, market, water, and education. It is agreed at zonal, regional and federal levels. A hotspot matrix is often used as a proxy for the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), whereas Priority 1 is equivalent to ‘Humanitarian Emergency’; Priority 2 indicates ‘Acute Food and Livelihood Crisis’; and Priority 3 indicates ‘Moderate Food Insecure or Chronically Food Insecure'.

3The funding amount and modalities of the CMAM intervention were agreed with the donors but operational areas were not predetermined.

4The hotspot classification is reassessed every three to four months. Any newly identified woredas that are not supported by partners are presented in ENCU coordination meetings; partners are invited to cover these if they have the necessary funding.

5To waive a certain procurement or sign-off procedure in order to make the process quicker for emergency situations (e.g. a procurement of a certain amount requiring sign-off by a higher level staff can now be signed off by a lower one).